Journal of Media Law and Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 1 Of

Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 1 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 2 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 3 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 4 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 5 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 6 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 7 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 8 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 9 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 10 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 11 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 12 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 13 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 14 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 15 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 16 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 17 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 18 of 502 Case 17-12443 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 19 of 502 1 CYCLE CENTER H/D 1-ELEVEN INDUSTRIES 100 PERCENT 107 YEARICKS BLVD 3384 WHITE CAP DR 9630 AERO DR CENTRE HALL PA 16828 LAKE HAVASU CITY AZ 86406 SAN DIEGO CA 92123 100% SPPEDLAB LLC 120 INDUSTRIES 1520 MOTORSPORTS 9630 AERO DR GERALD DUFF 1520 L AVE SAN DIEGO CA 92123 30465 REMINGTON RD CAYCE SC 29033 CASTAIC CA 91384 1ST AMERICAN FIRE PROTECTION 1ST AYD CO 2 CLEAN P O BOX 2123 1325 GATEWAY DR PO BOX 161 MANSFIELD TX 76063-2123 ELGIN IN 60123 HEISSON WA 98622 2 WHEELS HEAVENLLC 2 X MOTORSPORTS 241 PRAXAIR DISTRIBUTION INC 2555 N FORSYTH RD STE A 1059 S COUNTRY CLUB DRRIVE DEPT LA 21511 ORLANDO FL 32807 MESA AZ -

HITMAKERS – 6 X 60M Drama

HITMAKERS – 6 x 60m drama LOGLINE In Sixties London, the managers of the Beatles, the Stones and the Who struggle to marry art and commerce in a bid to become the world’s biggest hitmakers. CHARACTERS Andrew Oldham (19), Beatles publicist and then manager of the Rolling Stones. A flash, mouthy trouble-maker desperate to emulate Brian Epstein’s success. His bid to create the anti-Beatles turns him from Epstein wannabe to out-of-control anarchist, corrupted by the Stones lifestyle and alienated from his girlfriend Sheila. For him, everything is a hustle – work, relationships, his own psyche – but always underpinned by a desire to surprise and entertain. Suffers from (initially undiagnosed) bi-polar disorder, which is exacerbated by increasing drug use, with every high followed by a self-destructive low. Nobody in the Sixties burns brighter: his is the legend that’s never been told on screen, the story at the heart of Hitmakers. Brian Epstein (28), the manager of the Beatles. A man striving to create with the Beatles the success he never achieved in entertainment himself (as either actor or fashion designer). Driven by a naive, egotistical sense of destiny, in the process he basically invents what we think of as the modern pop manager. He’s an emperor by the age of 30 – but this empire is constantly at risk of being undone by his desperate (and – to him – shameful) homosexual desires for inappropriate men, and the machinations of enemies jealous of his unprecedented, upstart success. At first he sees Andrew as a protege and confidant, but progressively as a threat. -

Reporter Privilege: a Con Job Or an Essential Element of Democracy Maguire Center for Ethics and Public Responsibility Public Scholar Presentation November 14, 2007

Reporter Privilege: A Con Job or an Essential Element of Democracy Maguire Center for Ethics and Public Responsibility Public Scholar Presentation November 14, 2007 Two widely divergent cases in recent months have given the public some idea as to what exactly reporter privilege is and whether it may or may not be important in guaranteeing the free flow of information in society. Whether it’s important or not depends on point of view, and, sometimes, one’s political perspective. The case of San Francisco Giants baseball star Barry Bonds and the ongoing issues with steroid use fueled one case in which two San Francisco Chronicle reporters were held in contempt and sentenced to 18 months in jail for refusing to reveal the source of leaked grand jury testimony. According to the testimony, Bonds was among several star athletes who admitted using steroids in the past, although he claimed he did not know at the time the substance he was taking contained steroids. In the other, New York Times reporter Judith Miller served 85 days in jail over her refusal to disclose the source of information that identified a CIA employee, Valerie Plame. The case was complicated with political overtones dealing with the Bush Administration’s claims in early 2003 that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. A number of other reporter privilege cases were ongoing during the same time period as these two, but the newsworthiness and the subject matter elevated these two cases in terms of extensive news coverage.1 Particularly in the case of Miller, a high-profile reporter for what arguably is the most important news organization in the world, being jailed created a continuing story that was closely followed by journalists and the public. -

An Exclusive Member Experience

THE JOURNAL OF THE NASSAU COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION July/August 2019 www.nassaubar.org Vol. 68, No. 11 Follow us on Facebook NCBA COMMITTEE MEETING CALENDAR Page 22 An Exclusive SAVE THE DATES BBQ AT THE BAR Member Experience Thursday, September 5, 2019 5:30 p.m. at Domus By Ann Burkowsky See Insert and pg. 6 Being a member of the Nassau Coun- ty Bar Association means you are part of JUDICIARY NIGHT the largest suburban bar association in the Thursday, October 17, 2019 country, a thriving organization consisting 5:30 p.m. at Domus of nearly 5,000 attorneys and legal profes- See pg. 6 sionals who strive to successfully build and grow their careers within the legal field. As OPEN HOUSE members of the NCBA you have access to Thursday, October 24, 2019 an array of unprecedented, exclusive mem- 3:00 p.m.-7:00 p.m. at Domus ber benefits that many bar associations do Volunteer lawyers needed not offer. to give consultations. In addition to networking opportunities Contact Gale Berg at (516) 747-4070 or and social events, the NCBA provides its [email protected]. members with the opportunity to meet top legal practitioners, judges, specialists and authorities; take a stand on important WHAT’S INSIDE issues affecting our county and country; and obtain the tools to grow a successful Education/Constitutional Law practice. Academic Freedom: Who And What When asked about the benefit of being Does It Protect? Page 3 a member, NCBA President Richard D. Designated Duty: A University’s Collins shared that, “Being a member of the Photo by Ann Burkowsky Obligation to Students with Mental NCBA is the easiest way for an attorney to Health Issues Page 5 become more involved shaping the future of know is that the NCBA now offers FREE the legal community. -

Lee Edwards Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5q2nf31k No online items Preliminary Inventory of the Lee Edwards papers Finding aid prepared by Hoover Institution Library and Archives Staff Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2009, 2013 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Preliminary Inventory of the Lee 2010C14 1 Edwards papers Title: Lee Edwards papers Date (inclusive): 1878-2004 Collection Number: 2010C14 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 389 manuscript boxes, 12 card file boxes, 2 oversize boxes, 5 film reels, 1 oversize folder(146.4 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, memoranda, reports, studies, financial records, printed matter, and sound recordings of interviews and other audiovisual material, relating to conservatism in the United States, the mass media, Grove City College, the Heritage Foundation, the Republican Party, Walter Judd, Barry Goldwater, and Ronald Reagan. Includes extensive research material used in books and other writing projects by Lee Edwards. Also includes papers of Willard Edwards, journalist and father of Lee Edwards. Creator: Edwards, Lee, 1932- Creator: Edwards, Willard, 1902-1990 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please -

The Bush Revolution: the Remaking of America's Foreign Policy

The Bush Revolution: The Remaking of America’s Foreign Policy Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Lindsay The Brookings Institution April 2003 George W. Bush campaigned for the presidency on the promise of a “humble” foreign policy that would avoid his predecessor’s mistake in “overcommitting our military around the world.”1 During his first seven months as president he focused his attention primarily on domestic affairs. That all changed over the succeeding twenty months. The United States waged wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. U.S. troops went to Georgia, the Philippines, and Yemen to help those governments defeat terrorist groups operating on their soil. Rather than cheering American humility, people and governments around the world denounced American arrogance. Critics complained that the motto of the United States had become oderint dum metuant—Let them hate as long as they fear. September 11 explains why foreign policy became the consuming passion of Bush’s presidency. Once commercial jetliners plowed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, it is unimaginable that foreign policy wouldn’t have become the overriding priority of any American president. Still, the terrorist attacks by themselves don’t explain why Bush chose to respond as he did. Few Americans and even fewer foreigners thought in the fall of 2001 that attacks organized by Islamic extremists seeking to restore the caliphate would culminate in a war to overthrow the secular tyrant Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Yet the path from the smoking ruins in New York City and Northern Virginia to the battle of Baghdad was not the case of a White House cynically manipulating a historic catastrophe to carry out a pre-planned agenda. -

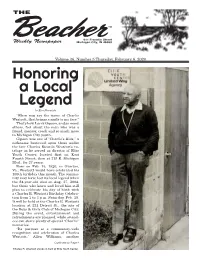

Honoring a Local Legend

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 36, Number 5 Thursday, February 6, 2020 Honoring a Local Legend by Kim Nowatzke “When you say the name of Charlie Westcott, that brings a smile to my face.” That’s how Larry Gipson, and so many others, feel about the man who was a friend, mentor, coach and so much more to Michigan City youth. Gipson was one of “Charlie’s Kids,” a nickname bestowed upon those under the late Charles Ricardo Westcott’s tu- telage as he served as director of Elite Youth Center, located fi rst on East Fourth Street, then at 318 E. Michigan Blvd., for 37 years. Born on Feb. 15, 1920, in Overton, Va., Westcott would have celebrated his 100th birthday this month. The commu- nity may have lost its local legend when the 84-year-old died on Aug. 27, 2004, but those who knew and loved him still plan to celebrate his day of birth with a Charles R. Westcott Birthday Celebra- tion from 1 to 3 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 15. It will be held at the Charles R. Westcott location at 321 Detroit St., the site of the Boys & Girls Club of Michigan City. During the event, entertainment and refreshments are planned, while attend- ees can share plenty of special “Charlie” memories. “Its purpose is a community-wide recognition and celebration of Charles Westcott,” Allen Williams, another Continued on Page 2 Charles R. Westcott stands in front of Elite Youth Center. THE Page 2 February 6, 2020 THE 911 Franklin Street • Michigan City, IN 46360 219/879-0088 Beacher Company Directory e-mail: News/Articles - [email protected] Don and Tom Montgomery Owners email: Classifieds - [email protected] Andrew Tallackson Editor http://www.thebeacher.com/ Drew White Print Salesman PRINTE ITH Published and Printed by Janet Baines Inside Sales/Customer Service T Becky Wirebaugh Typesetter/Designer T A S A THE BEACHER BUSINESS PRINTERS Randy Kayser Pressman Dora Kayser Bindery Delivered weekly, free of charge to Birch Tree Farms, Duneland Beach, Grand Beach, Hidden Shores, Long Beach, Michiana Shores, Michiana MI and Shoreland Hills. -

Het Verhaal Van De 340 Songs Inhoud

Philippe Margotin en Jean-Michel Guesdon Rollingthe Stones compleet HET VERHAAL VAN DE 340 SONGS INHOUD 6 _ Voorwoord 8 _ De geboorte van een band 13 _ Ian Stewart, de zesde Stone 14 _ Come On / I Want To Be Loved 18 _ Andrew Loog Oldham, uitvinder van The Rolling Stones 20 _ I Wanna Be Your Man / Stoned EP DATUM UITGEBRACHT ALBUM Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down The Road Apiece ALBUM DATUM UITGEBRACHT 10 januari 1964 EP Everybody Needs Somebody To Love Under The Boardwalk DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : (er zijn ook andere data, zoals DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : 17 april 1964 16, 17 of 18 januari genoemd Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down Home Girl I Can’t Be Satisfi ed 15 januari 1965 Label Decca als datum van uitbrengen) 14 augustus 1964 You Can’t Catch Me Pain In My Heart Label Decca REF : LK 4605 Label Decca Label Decca Time Is On My Side Off The Hook REF : LK 4661 12 weken op nummer 1 REF : DFE 8560 REF : DFE 8590 10 weken op nummer 1 What A Shame Susie Q Grown Up Wrong TH TH TH ROING (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 FIVE I Just Want To Make Love To You Honest I Do ROING ROING I Need You Baby (Mona) Now I’ve Got A Witness (Like Uncle Phil And Uncle Gene) Little By Little H ROLLIN TONS NOW VRNIGD TATEN EBRUARI 965) I’m A King Bee Everybody Needs Somebody To Love / Down Home Girl / You Can’t Catch Me / Heart Of Stone / What A Shame / I Need You Baby (Mona) / Down The Road Carol Apiece / Off The Hook / Pain In My Heart / Oh Baby (We Got A Good Thing SONS Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) If You Need Me Goin’) / Little Red Rooster / Surprise, Surprise. -

APRIL 1992 Vol LVIII No.2

Pm.·ftr1.11tty Acktr ,Ohio Vlct pr11.·ftr.Ed1und l.ftorri1,Vir9inia THE IESTCOTT FARILY QUARTERLY Record sec·ftr.Sharon F.Coltey,&eor9ia Issued qmterly Jamry,April,July,Oct Corr .m-ftrs.fterle lestcatt,lashlngton Noting activities of the Society. Fret Treasarer·ftr.Paul R.Le1ls,Connecticut to 1e1bers, nan-1e1bers $5.00 yearly. &emlogist-Rrs.Edu J.Lewh,Conmticut Editor - Pauline M. Dennis Registrar·ftrs.ftarcella lestcott,Vir9inia 1156 E. 8th ST I Chaphin·ftr .George S.lestcatt,Flarida Rifle, CO 81650 APRIL 1992 Vol LVIII no.2 NATIONAL NEWS WELCOME NEW SSWDA MEMBERS 826 "RS."ELANIE A. DENNISON 95009 WAIKALANIE IA-209 HILILANI HI 96789 827 "· ELAINE "ATHEWSON PEREIRA 181 KENYON AVE. WAKEFIELD RI 02879 828 "'" EVERETT "· HEATH RT. 1 BOX 188B DANBURY NH 03230 829 HRS.BERNICE W. KUHN 1224 HOWELL CT. NEWARK OH 43055 830 HRS.MAXINE ELIZABETH COREY BOX 22 LAWRENCE NS BOS lH CANADA 831 HI" ROBERT J, HADEEN PO BOZ 322 SUNNYSIDE WA 98944-0322 832 H/H LYLE D. VINCENT,Jr. 1100 ANN ST. PARKERSBURG WY 26101 833 H/H HURRAY RAY SMITH RT.2,BOX 29 RED OAK IA 51566 834 H/H STACEY A. HEAD RD 1 BOX 57 HAMPTON NY 12837 835 H. DARRYLL H. VANDETTA 1064 LOMA VISTA DR. LONG BEACH CA 90813 836 H. DYLAN YANDETTA RD 12, BOX 2547 WHITEHALL NY 12887 837 H. W. DANIEL YANDETTA RD 12, BOX 2547 WHITEHALL NY 12887 838 H. DONNA J, HERRICK 802 W. SADDLE PAYSON AZ 85541 839 HRS.GRACE B. ROBERTS PATTY RD. RR 1 BOX 283D DELANO TN 37325 840 H/" ROBIN D. -

Crystal Reports

CLE Course Sponsors (listed alphabetically by abbreviation) Thursday, December 31, 2020 Nym Sponsor Address Contact Phone , - ( ) - 1031EE 1031 Exchange Experts LLC 8101 E Prentice Ave #400 Grnwd Vill , CO 80111- J Sides 866-694-0204 Kcc 2335 Alaska Avenue El Segundo, CA 90245- H Schlager (310) 751-1841 21STCC 21st Communications Comp 405 S Humboldt St Denver, CO 80209 G Meyers 303 298 1090 360ADV 360 Advocacy Inst 1103 Parkview Blvd Colo Spgs, CO 80905- K Osborn ( 71) 957-8535 4LEVE 4L Events Llc 2609 Production Road Virginia Beach, VA 23454- A Millard (800) 241-3333 AAA Amer Arbitration Assoc 13455 Noel Road #1750 Dallas, TX 75240- C Rumney (972) 774-6927 AAAA Amer Acad Of Adoption Attys 2930 E. 96Th Street Indianapolis, IN 46240- E Freeby (817) 338-4888 AAACPA Amer Assn Of Atty Cpas 8647 Richmond Hwy, #639 Alexandria, VA 22309- N Ratner (703) 352-8064 AAAEXE Amer Assn of Airport Executive , S Dickerson 703 824 0500 AAALS Assn of Amer Law Schools 1201 Connecticut Ave #800 Wash, DC 20036 J Bauman 202 269 8851 AAARTA Amer Acad Asst Repo Tech Attys Po Box 33053 Wash, DC 20033- D Crouse (618) 344-6300 AABA Asian Amer Bar Assn 10 Emerson St #501 Denver, CO 80218 c/o Ravi Kanwal 303 781 4855 AABAA Advocates Against Batt & Abuse PO Box 771424 Steamboat Spgs, , CO 80477- D Moore (970) 879-2034 AACLLC AA-Adv Appraisals Consulting 436 E Main St #C Montrose, CO 81401 M W Johnson 970 249 1420 AADC Arizona Assn of Defense Coun 3507 N Central Ave #202 Phoenix, AZ 85012 602 212 2505 AAEL Equipment Leasing Assn 1625 Eye Street Nw Washington, DC 20006- -

As Judith Miller Sat in a Virginia Jail Cell After Her Failed Attempts to Keep

JOURNAL OF MEDIA LAW & ETHICS Editor ERIC B. EASTON, PROFESSOR OF LAW University of Baltimore School of Law EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS BENJAMIN BENNETT-CARPENTER, Special Lecturer, Oakland University (Michigan) WALTER M. BRASCH, Professor of Mass Comm., Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania L. SUSAN CARTER, Professor, Michigan State University LOUIS A. DAY, Alumni Professor, Louisiana State University ANTHONY FARGO, Associate Professor, Indiana University AMY GAJDA, Assistant Professor, University of Illinois STEVEN MICHAEL HALLOCK, Assistant Professor, Point Park University MARTIN E. HALSTUK, Associate Professor, Pennsylvania State University CHRISTOPHER HANSON, Associate Professor, University of Maryland ELLIOT KING, Professor, Loyola University Maryland JANE KIRTLEY, Silha Professor of Media Ethics & Law, University of Minnesota NORMAN P. LEWIS, Assistant Professor, University of Florida PAUL S. LIEBER, Assistant Professor, University of South Carolina KAREN M. MARKIN, Director of Research Development, University of Rhode Island KIRSTEN MOGENSEN, Associate Professor, Roskilde University (Denmark) KATHLEEN K. OLSON, Associate Professor, Lehigh University RICHARD J. PELTZ, Professor of Law, University of Arkansas-Little Rock School of Law KEVIN WALL SAUNDERS, Professor of Law, Michigan State University College of Law JAMES LYNN STEWART, Associate Professor, Nicholls State University DOREEN WEISENHAUS, Associate Professor, University of Hong Kong KYU HO YOUM, Jonathan Marshall First Amendment Chair Professor, Univ. of Oregon Journal of Media Law & Ethics, Volume 2, Numbers 1/2 (Winter/Spring 2010) 1 PREVIEW these new and recent titles at www.MarquetteBooks.com Jennifer Jacobs Henderson, Defending the Good Tomasz Pludowski (ed.), How the World’s News News: The Jehovah’s Witnesses’ Plan to Expand Media Reacted to 9/11: Essays from Around the the First Amendment (2010). -

Adventures In

BULLETIN Fall 2009 adventurEs in sCIENCE Ingree’sPort IncludesYear end P re board of trustees 2008–09 Jane Blake Riley ’77, p ’05 President contents James D. Smeallie p ’05, ’09 V ice President Keith C. Shaughnessy p ’04, ’08, ’10 T reasurer Philip G. Lake ’85 4 Pingree Secretary athletes Thanks Anthony G.L. Blackman p ’10 receive Interim Head of School All-American Nina Sacharuk Anderson ’77, p ’09 ’11 honors for stepping up to the plate. Kirk C. Bishop p ’06, ’06, ’08 Tamie Thompson Burke ’76, p ’09 Patricia Castraberti p ’08 7 Malcolm Coates p ’01 Honoring Therese Melden p ’09, ’11 Reflections: Science Teacher Even in our staggering economy, Theodore E. Ober p ’12 from Head of School Eva Sacharuk 16 Oliver Parker p ’06, ’08, ’12 Dr. Timothy M. Johnson Jagruti R. Patel ’84 you helped the 2008–2009 Pingree William L. Pingree p ’04, ’08 3 Mary Puma p ’05, ’07, ’10 annual Fund hit a home run. Leslie Reichert p ’02, ’07 Patrick T. Ryan p ’12 William K. Ryan ’96 Binkley C. Shorts p ’95, ’00 • $632,000 raised Joyce W. Swagerty • 100% Faculty and staff participation Richard D. Tadler p ’09 William J. Whelan, Jr. p ’07, ’11 • 100% Board of trustees participation Sandra Williamson p ’08, ’09, ’10 Brucie B. Wright Guess Who! • 100% class of 2009 participation Pictures from Amy McGowan p ’07, ’10 the archives 26 • 100% alumni leadership Board participation Parents Association President William K. Ryan ’96 • 15% more donations than 2007–2008 A Lumni L eadership Board President Cover Story: • 251 new Pingree donors board of overseers Adventures in Science Alice Blodgett p ’78, ’81, ’82 Susan B.