Music-Handbook.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birmingham Museums Supplement

BIRMINGHAM: ITS PEOPLE, ITS HISTORY Birmingham MUSEUMS Published by History West Midlands www.historywm.com fter six years of REVEALING BIRMINGHAM’S HIDDEN HERITAGE development and a total investment of BIRMINGHAM: ITS PEOPLE, ITS HISTORY A £8.9 million, The new ‘Birmingham: its people, its history’ galleries at Birmingham Museum & Art ‘Birmingham: its people, its Gallery, officially opened in October 2012 by the Birmingham poet Benjamin history’ is Birmingham Museum Zephaniah, are a fascinating destination for anyone interested in history. They offer an & Art Gallery’s biggest and most insight into the development of Birmingham from its origin as a medieval market town ambitious development project in through to its establishment as the workshop of the world. But the personal stories, recent decades. It has seen the development of industry and campaigns for human rights represented in the displays restoration of large parts of the have a significance and resonance far beyond the local; they highlight the pivotal role Museum’s Grade II* listed the city played in shaping our modern world. From medieval metalwork to parts for building, and the creation of a the Hadron Collider, these galleries provide access to hundreds of artefacts, many of major permanent exhibition which have never been on public display before. They are well worth a visit whether about the history of Birmingham from its origins to the present day. you are from Birmingham or not. ‘Birmingham: its people, its The permanent exhibition in the galleries contains five distinct display areas: history’ draws upon the city’s rich l ‘Origins’ (up to 1700) – see page 1 and nationally important l ‘A Stranger’s Guide’ (1700 to 1830) – see page 2 collections to bring Birmingham’s l ‘Forward’ (1830 to 1909) – see page 3 history to life. -

Sum Mer Music

EX CATHEDRA excathedra.co.uk Mus er ic m m u S by Candlelight CHOIR | CONSORT | ORCHESTRA | EDUCATION ARTISTIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR JEFFREY SKIDMORE Summer Music by Candlelight St Peter’s Church, Wolverhampton Saturday 5 June 2021, 5pm & 8pm Hereford Cathedral Wednesday 9 June 2021, 3pm & 7.30pm St John’s Smith Square, London Thursday 10 June 2021, 5pm & 8pm Symphony Hall, Birmingham Sunday 13 June 2021, 4pm Programme Hymnus Eucharisticus Benjamin Rogers (1614-1698) Iam lucis orto sidere 6th century plainchant The Windhover (Dawn Chorus, 2020) Liz Dilnot Johnson (b.1964) Sumer is icumen in 13th century English Cuckoo! (1936) Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), arr. Jeffrey Skidmore Revecy venir du Printans Claude le Jeune (c.1528/1530-1600) READING - In defense of our overgrown garden - Matthea Harvey (b.1973) The Gallant Weaver (1997) James MacMillan (b.1959) READING - i thank You God most for this - e.e.cummings (1894-1962) Hymn to St Cecilia (1941- 42) Benjamin Britten READING - Gingo Biloba (1819) - Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) Trois Chansons (1914-15) Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) I Nicolette II Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis III Ronde READING - maggie and milly and molly and may - e.e.cummings La Mer (1943) Charles Trenet (1913-2001), arr. Jeffrey Skidmore Summer Holiday (1963) Bruce Welch (b.1941) and Brian Bennett (b.1940), arr. Jeffrey Skidmore anyone lived in pretty how town (2018) Geoff Haynes (b.1959) READING - The evening sun retreats along the lawn (Summer Requiem 2015) - Vikram Seth (b.1952) Saint Teresa’s Bookmark (2018) Penelope Thwaites (b.1944) Te lucis ante terminum 7th century plainchant Night Prayer (2016) Alec Roth (b.1948) We would like to offer our thanks for their help and support to: - The Rev Preb. -

Download Full Biography

Duncan Honeybourne Full Biography 900 words "The heroic Duncan Honeybourne" (Musical Opinion) enjoys a colourful and diverse career as a pianist and in music education. Reviews have commended his "glittering performances" and “suave confidence” (International Piano), “terrific intensity and touches of panache” (International Record Review), "intellectual and physical stamina" (Musical Opinion) and “delicate chemistry of touch and arm weight” (Gramophone). Fanfare magazine (USA) remarked: “Honeybourne’s performance is simply beautiful, even in its most powerful and haunting moments”, whilst American Record Guide commented: "Honeybourne's playing is always polished and refined." His debut in 1998 as concerto soloist at Symphony Hall, Birmingham and the National Concert Hall, Dublin, was broadcast on radio and television, and he gave recital debuts in London, Dublin, Paris, and at international festivals in Belgium and Switzerland. Duncan's debut CD was described by Gramophone magazine as “not to be missed by all lovers of English music”, whilst BBC Music Magazine reported: “There are gorgeous things here. Hard to imagine better performances.” Honeybourne has toured extensively in the UK, Ireland and Europe as solo and lecture recitalist, concerto soloist and chamber musician, appearing at many major venues and leading festivals. His solo performances have been frequently broadcast on BBC Radio 3 and TV (UK), RTÉ (Ireland), Radio France Musique, Radio Suisse Romande, Austrian, Belgian, Dutch, Finnish and German Radio, SABC (South Africa), ABC (Australia) and Radio New Zealand. Duncan's engagements for regional music societies and arts centres across England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland have included hundreds of solo recitals as well as many partnerships with renowned artists and ensembles. -

The Forge Brochure V7.Pdf

ABOVE AND BEYOND BJD ARE UNIQUE PROPERTY DEVELOPERS, WITH A PASSION FOR AUTHENTICITY. Over the past twelve years, we have specialised in unique renovation projects; extraordinary sites and developments which have allowed us to reinstate classic architecture back to its former glory. Due to our rich and experienced background in traditional craftsmanship, we understand the importance of detail and quality. With our diverse team, we successfully restore, revive and transform beautiful historic properties back to their origins. A number of our projects have been featured in magazines such as ‘Homes & Gardens’ and ‘Bedrooms, Bathrooms & Kitchens’. The Forge - Digbeth is our most recent development, which we have again partnered alongside Cedar Invest. With an extensive portfolio of commercial and residential ventures throughout the UK, Cedar offer over 60 years of combined experience and expertise which have helped turn The Forge from vision into reality. Together as custodians, we reinvent iconic properties preserving their history for generations to come. DELIVERING LUXURY LIFESTYLES THE FORGE IN DIGBETH PROVIDES Just moments away from Birmingham’s thriving PURCHASERS THE OPPORTUNITY TO City Centre and less than 5 Minutes away from Birmingham New Street and Grand Central it is easy ENJOY ALL THAT BIRMINGHAM HAS TO to forget you are so centrally located. The Forge is a OFFER ACROSS A WIDE VARIETY OF HOME stunning development that will deliver 140 luxury CHOICES FROM FIRST TIME BUYERS TO apartments in one and two bedroom residences. ESTABLISHED -

Edward Elgar: the Dream of Gerontius Wednesday, 7 March 2012 Royal Festival Hall

EDWARD ELGAR: THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS WEDNESDAY, 7 MARCH 2012 ROYAL FESTIVAL HALL PROGRAMME: £3 royal festival hall PURCELL ROOM IN THE QUEEN ELIZABETH HALL Welcome to Southbank Centre and we hope you enjoy your visit. We have a Duty Manager available at all times. If you have any queries please ask any member of staff for assistance. During the performance: • Please ensure that mobile phones, pagers, iPhones and alarms on digital watches are switched off. • Please try not to cough until the normal breaks in the music • Flash photography and audio or video recording are not permitted. • There will be a 20-minute interval between Parts One and Two Eating, drinking and shopping? Southbank Centre shops and restaurants include Riverside Terrace Café, Concrete at Hayward Gallery, YO! Sushi, Foyles, EAT, Giraffe, Strada, wagamama, Le Pain Quotidien, Las Iguanas, ping pong, Canteen, Caffè Vergnano 1882, Skylon and Feng Sushi, as well as our shops inside Royal Festival Hall, Hayward Gallery and on Festival Terrace. If you wish to contact us following your visit please contact: Head of Customer Relations Southbank Centre Belvedere Road London SE1 8XX or phone 020 7960 4250 or email [email protected] We look forward to seeing you again soon. Programme Notes by Nancy Goodchild Programme designed by Stephen Rickett and edited by Eleanor Cowie © London Concert Choir 2012 www.london-concert-choir.org.uk London Concert Choir – A company limited by guarantee, incorporated in England with registered number 3220578 and with registered charity number 1057242. Wednesday 7 March 2012 Royal Festival Hall EDWARD ELGAR: THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS Mark Forkgen conductor London Concert Choir Canticum semi-chorus Southbank Sinfonia Adrian Thompson tenor Jennifer Johnston mezzo soprano Brindley Sherratt bass London Concert Choir is grateful to Mark and Liza Loveday for their generous sponsorship of tonight’s soloists. -

ARSM (Associate of the Royal Schools of Music)

Qualification Specification ARSM (Associate of the Royal Schools of Music) Level 4 Diploma in Music Performance September 2020 Qualification Specification: ARSM Contents 1. Introduction 4 About ABRSM 4 About this qualification specification 5 About this qualification 5 Regulation (UK) 6 Regulation (Europe) 7 Regulation (Rest of world) 8 2. ARSM diploma 9 Syllabuses 9 Exam Regulations 9 Malpractice and maladministration 9 Entry requirements 10 Exam booking 11 Access (for candidates with specific needs) 11 Exam content 11 How the exam works 11 3. ARSM syllabus 14 Introducing the qualification 14 Exam requirements and information 14 • Subjects available 14 • Selecting repertoire 14 • Preparing for the exam 17 4. Assessment and marking 19 Assessment objectives 19 Mark allocation 19 Result categories 20 Synoptic assessment 20 Awarding 20 Marking criteria 20 5. After the exam 23 Results 23 Exam feedback 23 © 2016 by The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music. Updated in 2020. 6. Other assessments 24 DipABRSM, LRSM, FRSM 24 Programme form 25 Index 27 This September 2020 edition contains updated information to cover the introduction of a remotely-assessed option for taking the ARSM exam. There are no changes to the existing exam content and requirements. Throughout this document, the term ‘instrument’ is used to include ‘voice’ and ‘piece’ is used to include song. 1. Introduction About ABRSM At ABRSM we aim to support learners and teachers in every way we can. One way we do this is through the provision of high quality and respected music qualifications. These exams provide clear goals, reliable and consistent marking, and guidance for future learning. -

A Menuhin Centenary Celebration

PLEASE A Menuhin Centenary NOTE Celebration FEATURING The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment of any kind during performances is strictly prohibited The Lord Menuhin Centenary Orchestra Philip Burrin - Conductor FEBRUARY Friday 19, 8:00 pm Earl Cameron Theatre, City Hall CORPORATE SPONSOR Programme Introduction and Allegro for Strings Op.47 Edward Elgar (1857 - 1934) Solo Quartet Jean Fletcher Violin 1 Suzanne Dunkerley Violin 2 Ross Cohen Viola Liz Tremblay Cello Absolute Zero Viola Quartet Sinfonia Tomaso Albinoni (1671 – 1751) “Story of Two Minstrels” Sancho Engaño (1922 – 1995) Menuetto Giacomo Puccini (1858 – 1924) Ross Cohen, Kate Eriksson, Jean Fletcher Karen Hayes, Jonathan Kightley, Kate Ross Two Elegiac Melodies Op.34 Edvard Grieg (1843 – 1907) The Wounded Heart The Last Spring St Paul’s Suite Op. 29 no.2 Gustav Holst (1874 – 1934) Jig Ostinato Intermezzo Finale (The Dargason) Solo Quartet Clare Applewhite Violin 1 Diane Wakefield Violin 2 Jonathan Kightley Viola Alison Johnstone Cello Intermission Concerto for Four Violins in B minor Op.3 No.10 Antonio Vivaldi (1678 – 1741) “L’estro armonico” Allegro Largo – Larghetto – Adagio Allegro Solo Violins Diane Wakefield Alison Black Cal Fell Sarah Bridgland Cello obbligato Alison Johnstone Concerto Grosso No. 1 Ernest Bloch (1880 – 1959) for Strings and Piano Obbligato Prelude Dirge Pastorale and Rustic Dances Fugue Piano Obbligato Andrea Hodson Yehudi Menuhin, Lord Menuhin of Stoke d’Abernon, (April 22, 1916 - March 12, 1999) One of the leading violin virtuosos of the 20th century, Menuhin grew up in San Francisco, where he studied violin from age four. He studied in Paris under the violinist and composer Georges Enesco, who deeply influenced his playing style and who remained a lifelong friend. -

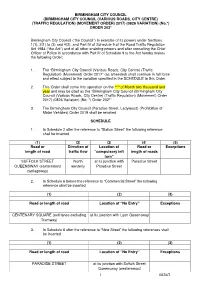

Traffic Movement Variation (TRO)

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL (BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL (VARIOUS ROADS, CITY CENTRE) (TRAFFIC REGULATION) (MOVEMENT ORDER) 2017) (0826 VARIATION) (No.*) ORDER 202* Birmingham City Council (“the Council”) in exercise of its powers under Sections 1(1), 2(1) to (3) and 4(2), and Part IV of Schedule 9 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 (“the Act”) and of all other enabling powers and after consulting the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to the Act hereby makes the following Order: 1. The “Birmingham City Council (Various Roads, City Centre) (Traffic Regulation) (Movement) Order 2017” (as amended) shall continue in full force and effect subject to the variation specified in the SCHEDULE to this Order. 2. This Order shall come into operation on the ** th of Month two thousand and year and may be cited as the “Birmingham City Council (Birmingham City Council (Various Roads, City Centre) (Traffic Regulation) (Movement) Order 2017) (0826 Variation) (No. *) Order 202*”. 3. The Birmingham City Council (Paradise Street, Ladywood) (Prohibition of Motor Vehicles) Order 2019 shall be revoked SCHEDULE 1. In Schedule 2 after the reference to “Station Street” the following reference shall be inserted (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Road or Direction of Location of Road or Exceptions length of road traffic flow “compulsory left length of roads turn” SUFFOLK STREET North at its junction with Paradise Street QUEENSWAY (easternmost westerly Paradise Street carriageway) 2. In Schedule 6 before the reference to “Commercial Street” the following reference shall be inserted (1) (2) (3) Road or length of road Location of “No Entry” Exceptions CENTENARY SQUARE (exit lanes excluding at its junction with Lyon Queensway Tramway) 3. -

ABRSM Exam Regulations International 2020

ABRSM Exam Regulations International 2020 Visit www.abrsm.org for online exam services and up-to-date information Contents About ABRSM and these Exam Regulations ............................................................ 4 1 Exam subjects ....................................................................................................................... 5 2 Regulated qualifications ................................................................................................... 5 3 Prerequisites ......................................................................................................................... 5 4 Introduction and overlap of syllabuses ...................................................................... 6 5 Applicant’s role and responsibilities ........................................................................... 6 6 Exam entry ............................................................................................................................. 6 7 Payment .................................................................................................................................. 7 8 Withdrawals, non-attendance and fee refunds.........................................................7 9 Access (for candidates with specific needs) .............................................................7 Entering for the exam, 7 Supporting evidence, 7 Personal data, 8 Alternative to graded exams, 8 10 Practical exam dates ......................................................................................................... -

Wells Angels G Iving Gifted Children a Chance the Angels’ Newsletter ISSUE 1 - SPRING 2019

Wells Angels G iving gifted children a chance the angels’ newsletter ISSUE 1 - SPRING 2019 Welcome to the first Wells Cathedral Chorister Trust newsletter of 2019. Many of you will be used to hearing our wonderful choir singing in the cathedral. What you may not know is how much work and dedication goes into producing this sublime music. We hope our new termly newsletter will give you a glimpse ‘behind the scenes’ of what the choristers get up to; what they achieve in school and on the sports fields as well as training daily to sing for us. The Chorister Trust is extremely grateful to our Wells Angels. Every contribution really does make a difference, often the difference that enables some choristers Pancake Fun! Some of our choristers took a break from their lessons and duties to to take up their places in the Choir and take part in a Shrove Tuesday Pancake Race, as part of a photoshoot for local media. develop into top musicians. Thankfully, the choristers involved were all expert flippers and there wasn’t too much The first of our Wells Angels ‘open pancake to clear up from Vicars’ Close or the Cloisters! (Photo: Jason Bryant) rehearsals’, to which all of our Angels are warmly invited, took place on Saturday 16 March. These are a termly opportunity to eavesdrop on one of the choristers’ daily events and see them at work. The dates for the next two open rehearsals are shown over the page. We also have another important date for your diaries. Our choristers are performing an informal concert, to include the toe-tapping fun that is Captain Noah & His Floating Zoo in the Cathedral on Saturday 4th May at 1pm. -

Moon, Sun & All Things

Moon, sun & all things BAROQUE MUSIC FROM LATIN AMERICA – 2 Ex Cathedra Jeffrey Skidmore Moon, sun & all things Jeffrey Skidmore writes … It is not surprising that Hanacpachap cussicuinin is so widely performed throughout Latin America and also seems to capture the imagination of all who hear it outside this seductive region. The music is noble, magical and haunting and is the earliest printed polyphony from the continent of South America. It is set for four voices in Sapphic verse in the Quechua language. The colourful imagery of the sequence of prayers skilfully mixes Inca and Christian imagery, with its references to stores of silver and gold, life without end, deceitful jaguars and sins of the devil. The singers may sing it ‘in processions entering the church’. It makes an extraordinarily powerful beginning to any service, concert, or recording. It is recorded here for the third time by Ex Cathedra with new orchestrations and new verses. It is surprising that it is so often performed using only the first two of the twenty verses given in the source. Moon, sun and all things is an anthology of Latin American music from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, chosen from the vast amount of extraordinary repertoire I discovered on research visits to the USA, Mexico and Bolivia. I worked in the Loeb Music Library at Harvard University, the Puebla Cathedral Archive and the Bolivian National Library in Sucre. I met many musicians in the National Arts Centre in Mexico City and in the Association for Art and Culture (APAC) in Santa Cruz. These were wonderful trips and I made many new friends who were companions and guides giving generously of their time: Salua Delalah (German Embassy), Ton de Wit (Prins Claus Foundation), Cecilia Kenning de Mansilla (APAC) and Josefina Gonsález (Saint Cecilia Choir, Puebla). -

Birmingham the Heart and Soul of the West Midlands Birmingham 2–3 the Heart and Soul of the West Midlands

Birmingham The heart and soul of the West Midlands Birmingham 2–3 The Heart and Soul of the West Midlands Brilliant Birmingham Birmingham Facts and Stats Welcome to Birmingham, the The second largest city in the UK, rich in Birmingham Town Hall and the Argent history and scattered with hidden gems, Centre. Birmingham’s innovation continues UK’s largest regional city: Birmingham is a hub of culture and today, being home to one of the UK’s a multicultural and innovation. With influences from across the premier research universities, as well as world, you can encounter anything from a Britain’s leading digital hub. innovative heartland at the English folk festival to Brazillian street art centre of Britain’s new with a world of experiences in between. However, Birmingham’s history lays far Divided into distinct quarters, the city centre beyond the borders of the West Midlands. Total population: Population growth to 2035: Percentage of people aged under 25: railway revolution. offers a unique mix of cultural attractions, as Birmingham is a multicultural city, which well as a range of restaurants, including celebrates its links to numerous countries several Michelin starred and countless bars and cultures. The city hosts over 50 festivals and clubs. Birmingham has something to throughout the year to celebrate diversity in m % % offer each of the 34 million visitors who are it’s own spectacular fashion. Welcoming the 1.1 16 37 drawn to the city every year. Chinese New Year in style, Birmingham’s free annual street festival attracts up to 30,000 Birmingham has a history of innovation and people.