Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Entertainment and Media Outlook 2010 2 Indian Entertainment and Media Outlook 2010 Message

Indian entertainment and media outlook 2010 2 Indian entertainment and media outlook 2010 Message To our clients and friends both in and beyond the entertainment and media industry : Welcome to the 2010 edition of PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Indian Entertainment and Media (E&M) Outlook, covering the forecast period of 2010–2014. Our forecasts and analysis for this edition focus on eight major E&M industry segments and one emerging segment. Each segment details out the key trends observed and challenges faced apart from providing the prospects for the segment. In the industry overview section, we have highlighted the key theme observed during 2009 and what we perceive as future trends in the coming years. We have a chapter on the tax and regulatory impact on the various E&M segments and for the very first time we have included a chapter on how technology can be leveraged in the E&M industry. In 2009, the economy severely impacted the world, translating into steep declines in advertisement as well as consumer spending. India though impacted, did manage to show growth with increased consumer spending as well as innovative action on the part of the industry. Against this backdrop, across the world, except certain markets, speed of digital spending increased due to changing consumer behavior as well as technology available to deliver the same. In India, while the spend on digital media is likely to grow, it is unlikely that it will dominate in the forecast period. This is largely due to the relative unavailability as well as unaffordability of the broadband and mobile infrastructure. -

Jagran Prakashan Limited Announces Q4 FY12

Jagran Prakashan Limited announces FY12 results Consolidated Operating Revenues up by 11.02% to Rs 1355.66 crores; Recommended Final Dividend of Rs 3.50 per share i.e 175% of paid up capital. Annual Results FY12 [(all comparisons with FY11) (Stand Alone)] Operating Revenues at Rs 1244.41crores, up by 11.57% from Rs 1115.32 crores. Advertisement Revenues at Rs 850.01crores, up by 10.90% from Rs 766.48 crores. Circulation Revenues at Rs 244.47 crores, up by 9.63% from Rs 222.99 crores. Event and Outdoor Revenues at Rs 113.20 crores, up by 20.49% from Rs 93.95 crores. Digital Revenues (excluding Advertisement Revenue) at Rs 8.24 crores, up by 23.17% from Rs 6.69 crores. Operating Profits at Rs 312.62 crores, as against Rs 342.17 crores. PAT (before adjustment of unrealised foreign exchange fluctuation) of Rs 190.50 crores as against Rs 204.78 crores (both net of tax). EPS (before adjustment of unrealised foreign exchange fluctuation) of Rs 6.02 as against Rs 6.47. PAT at Rs 179.64 crores, as against Rs 205.83 crores. EPS (annualized) of Rs 5.68 as against Rs 6.51. Q4FY12 [(all comparisons with Q4FY11) (Stand Alone)] Operating Revenues at Rs 310.41 crores, up by 9.83% from Rs 282.62 crores. Advertisement Revenues at Rs 210.33 crores, up by 11.45% from Rs 188.73 crores. Circulation Revenues at Rs 62.79 crores, up by 12.39% from Rs 55.87 crores. Event and Outdoor Revenues at Rs 27.94 crores as against Rs 29.23 crores. -

MARCH 2021 Current Affairs Best Revision Questions

MARCH 2021 Current Affairs Best Revision Questions Q) Consider the following statements. a) ISRO successfully launched Brazil’s optical earth observation satellite, Amazonia-1, and 18 co-passenger satellites b) The satellites were carried onboard the PSLV-C51, the 53rd flight of ISRO’s launch vehicle and the first dedicated mission of its commercial arm, NewSpace India Ltd. Which of the above statements is/are correct? A. 1 only B. 2 only C. Both 1 and 2 D. Neither 1 nor 2 Ans - C The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) on Sunday successfully launched Brazil’s optical earth observation satellite, Amazonia-1, and 18 co-passenger satellites — five from India and 13 from the U.S. — from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre at Sriharikota. The satellites were carried onboard the PSLV-C51, the 53rd flight of ISRO’s launch vehicle, and the first dedicated mission of its commercial arm, NewSpace India Ltd. The mission was undertaken under a commercial arrangement with Spaceflight Inc., U.S. Q) Consider the following statements: a) Indian Air Force will perform at an airshow at the Galle Face in Colombo as part of the 70th-anniversary celebrations of the Sri Lankan Air Force (SLAF) b) This is the first performance for the Suryakiran Aerobatic Team (SKAT) outside India since it was resurrected in 2015 with the Hawk advanced jet trainers. Which of the above statements is/are correct? A. 1 only 1 TELEGRAM LINK: https://t.me/opdemy WEBSITE: www.opdemy.com B. 2 only C. Both 1 and 2 D. Neither 1 nor 2 Anc - C The Suryakiran Aerobatic Team (SKAT) and the Sarang helicopter display team, along with the light combat aircraft, of the Indian Air Force, will perform at an airshow at the Galle Face in Colombo from March 3 to 5 as part of the 70th-anniversary celebrations of the Sri Lankan Air Force (SLAF). -

Jagran Prakashan Limited

LETTER OF OFFER THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION This Letter of Offer is sent to you as a registered Equity Shareholder of Jagran Prakashan Limited (the “Company”) as on the Record Date in accordance with Securities and Exchange Board of India (Buy Back of Securities) Regulations, 1998, as amended (the “Buyback Regulations”). If you require any clarifications about the action to be taken, you should consult your stock broker or investment consultant or the Manager to the Buyback Offer i.e Ernst & Young Merchant Banking Services Private Limited or to the Registrar to the Buyback Offer i.e Karvy Computershare Private Limited. Please refer to the section on ‘Definitions’ for the definition of the capitalized terms used herein. Jagran Prakashan Limited Corporate Identity Number: L22219UP1975PLC004147 Registered Office address: Jagran Building, 2, Sarvodaya Nagar, Kanpur – 208005; Website: www.jplcorp.in Contact Person: Mr Amit Jaiswal, Company Secretary and Compliance Officer Tel: 0512-2216161; Fax: 0512-2230625, E-mail: [email protected] CASH OFFER FOR BUYBACK OF UPTO 1,50,00,000 (ONE CRORE AND FIFTY LAKH) FULLY PAID-UP EQUITY SHARES OF FACE VALUE OF INR 2 (INDIAN RUPEES TWO ONLY) EACH, REPRESENTING 4.82% OF THE TOTAL NUMBER OF EQUITY SHARES IN THE ISSUED, SUBSCRIBED AND PAID-UP EQUITY SHARE CAPITAL OF THE COMPANY, FROM ALL THE EXISTING SHAREHOLDERS/BENEFICIAL OWNERS OF EQUITY SHARES OF THE COMPANY AS ON THE RECORD DATE i.e. FRIDAY, 15TH JUNE 2018, ON A PROPORTIONATE BASIS (SUBJECT TO SMALL SHAREHOLDER RESERVATION), -

Jagran Prakashan Limited Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers Scrip Code: 532705 Dalal Street, ISIN: INE 199001027 Mumbai - 40000 L

THE WORLD'S LARGEST READ DAILY Jagran August 13, 2021 l. Manager - CRD, BSE Limited, Re: Jagran Prakashan Limited Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers Scrip Code: 532705 Dalal Street, ISIN: INE 199001027 Mumbai - 40000 l 2. Listing Manager, National Stock Exchange of India Ltd., Re: Jagran Prakashan Limited 'Exchange Plaza' Symbol: JAGRAN Bandra Kurla Complex, Dalal Street !SIN: INE199G01027 Bandra (E), Mumbai-400051 Dear Sir I Madam, Subject: Buyback of equity shares of face value of INR 2/- each ("Equity Shares") by Jagran Prakashan Limited (the "Company") from the open market through stock exchanges ("Buyback") - Intimation for closure of the Buyback This is in furtherance to, (i) our letter dated Tuesday, March 02, 2021, informing the outcome of the meeting of the Board of Directors of the Company ("Board") approving the Buyback; and (ii) our letter dated Thursday, March 04, 2021 regarding submission of the public announcement dated Wednesday, March 03, 2021 for the Buyback ("Public Announcement"). Pursuant to the resolution passed by the Board on Tuesday, March 02, 2021, the Company was authorised to buyback its Equity Shares from the open market through stock exchange mechanism, for an aggregate amount not exceeding INR 118,00,00,000 (Indian Rupees One Hundred and Eighteen Crores Only), excluding the brokerage, costs, fees, turnover charges, taxes such as buyback tax, securities transaction tax, goods and service tax (if any) and income tax, stamp duty, printing expenses, filing fees, advisors fees and other incidental and related expenses and charges ( collectively referred to as "Transaction Costs") ("Maximum Buyback Size"), and at a price not exceeding INR 60 (Indian Rupees Sixty Only) per Equity Share ("Maximum Buyback Price"). -

1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 2604124 30/09/2013 Trading As ;BINOD TEXTILES Address for Service In

Trade Marks Journal No: 1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 PUJA 2604124 30/09/2013 Mr Binod Kumar Todi MRS. SUDHA TODI MR. VIJAY KUMAR TODI MRS. SAVITA TODI trading as ;BINOD TEXTILES 6,RAGHUNANDAN LANE,KOLKATA 700006,WEST BENGAL Manufacturer, Merchant, and Trader. Address for service in India/Attorney address: IPR HOUSE.COM 89/269/270, BANGUR PARK, PARK TOWER, 4TH FLOOR, ROOM NO. 401, RISHRA - 712248, HOOGHLY, WEST BENGAL Used Since :31/12/1980 To be associated with: 419649 KOLKATA "Hosiery Goods, Undergarments, Vests, Briefs, Panties" 3648 Trade Marks Journal No: 1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 3043675 29/08/2015 BRAINBEES SOLUTIONS PRIVATE LIMITED. Rajashree Business Park, Plot No 114, Survey No 338, Tadiwala Road, Nr. Sohrab Hall, Pune-411001, Maharashtra, India MERCHANTS & TRADERS COMPANY INCORPORATED UNDER THE COMPANIES ACT, 1956 Address for service in India/Attorney address: LEGATARIAN IPR CONSULTANTS LLP 304, A-Wing, Pranavshree, Riddhi Siddhi Paradise, Near Manas Society, Dhayari-411041, Pune, Maharashtra, India Used Since :20/12/2014 MUMBAI ALL KINDS OF CLOTHING , FOOTWEAR AND HEADGEAR FOR BABIES. 3649 Trade Marks Journal No: 1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 CADRE 3074790 08/10/2015 VIKAS TANK trading as ;VIKAS TANK HOUSE NO- 2785, KHAZANE WALON KA RASTA, DARJIYON KA CHOUHARA, JAIPUR, RAJASTHAN M/S VIKAS TANK Address for service in India/Attorney address: MARK R SERVICES C-365 NIRMAN NAGAR KINGS ROAD JAIPUR RAJASTHAN Used Since :01/09/2015 AHMEDABAD CLOTHINGS FOR MEN, WOMEN AND KIDS, HEAD GEARS AND SHOES INCLUDING IN CLASS 25 3650 Trade Marks Journal No: 1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 3085949 27/10/2015 SHRI RAMZAN ALI B. -

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford

1 Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford IN NEED OF A LEVESON? JOURNALISM IN INDIA IN TIMES OF 1 PAID NEWS AND ‘PRIVATE TREATIES’ By Anuradha Sharma2 Hilary & Trinity 2013 Sponsor: Thomson Reuters Foundation ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 I take part of my title from Arghya Sengupta’s article “Does India need its Leveson?” Free Speech Debate website, May 13, 2013, http://freespeechdebate.com/en/discuss/does-india-need-its-leveson/ 2 Anuradha Sharma was a journalist fellow at the Reuters Institute in 2013. She worked at the Economic Times from July 2008 to January 2011. She is now a freelance journalist writing on politics and culture in South Asia. 2 To the Reuters Institute, I am grateful for selecting me for the programme. To the Thomson Reuters Foundation, I shall always remain indebted for being my sponsor, and for making this experience possible for me. Supervision by John Lloyd was a sheer privilege. My heartfelt gratitude goes to John for being a wonderful guide, always ready with help and advice, and never once losing patience with my fickle thoughts. Thank you, James Painter for all the inputs, comments and questions that helped me to shape my research paper. Dr. David Levy and. Tim Suter‘s contributions to my research were invaluable. Prof. Robert Picard‘s inputs on global media businesses and observations on ―private treaties‖ were crucial. My heartfelt thanks also go to Alex, Rebecca, Kate, Tanya and Sara for taking care of every small detail that made my Oxford experience memorable and my research enriching. To the other fellows I shall remain indebted for the gainful exchanges and fun I had in Oxford. -

Jagran Prakashan Limited Jagran Prakashan

Jagran Prakashan Limited Q1FY17 AnnualResult Presentation Presentation – FY17 1 Safe Harbor This presentation and the accompanying slides (the “Presentation”), which have been prepared by Jagran Prakashan Limited (the “Company”), have been prepared solely for information purposes and do not constitute any offer, recommendation or invitation to purchase or subscribe for any securities, and shall not form the basis or be relied on in connection with any contract or binding commitment what so ever. No offering of securities of the Company will be made except by means of a statutory offering document containing detailed information about the Company. This Presentation has been prepared by the Company based on information and data which the Company considers reliable, but the Company makes no representation or warranty, express or implied, whatsoever, and no reliance shall be placed on, the truth, accuracy, completeness, fairness and reasonableness of the contents of this Presentation. This Presentation may not be all inclusive and may not contain all of the information that you may consider material. Any liability in respect of the contents of, or any omission from, this Presentation is expressly excluded. Certain matters discussed in this Presentation may contain statements regarding the Company’s market opportunity and business prospects that are individually and collectively forward-looking statements. Such forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to known and unknown risks, uncertainties and -

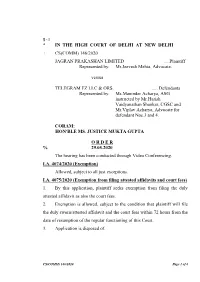

146/2020 JAGRAN PRAKASHAN LIMITED ...Plaintiff

$~1 * IN THE HIGH COURT OF DELHI AT NEW DELHI + CS(COMM) 146/2020 JAGRAN PRAKASHAN LIMITED .....Plaintiff Represented by: Mr.Jeevesh Mehta, Advocate. versus TELEGRAM FZ LLC & ORS. ..... Defendants Represented by: Ms.Maninder Acharya, ASG instructed by Mr.Harish Vaidyanathan Shankar, CGSC and Mr.Viplav Acharya, Advocate for defendant Nos.3 and 4. CORAM: HON'BLE MS. JUSTICE MUKTA GUPTA O R D E R % 29.05.2020 The hearing has been conducted through Video Conferencing. I.A. 4074/2020 (Exemption) Allowed, subject to all just exceptions. I.A. 4075/2020 (Exemption from filing attested affidavits and court fees) 1. By this application, plaintiff seeks exemption from filing the duly attested affidavit as also the court fees. 2. Exemption is allowed, subject to the condition that plaintiff will file the duly sworn/attested affidavit and the court fees within 72 hours from the date of resumption of the regular functioning of this Court. 3. Application is disposed of. CS(COMM) 146/2020 Page 1 of 6 CS(COMM) 146/2020 & I.A. 4073/2020 (under Order XXXIX Rule 1 and 2 CPC) 1. Plaint be registered as suit. 2. Issue summons in the suit and notice on the application. 3. Learned Additional Solicitor General for the Union of India enters appearance on behalf of defendant Nos.3 and 4 which are Department of Telecommunications and Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology and states that the defendant Nos.3 and 4 have no control whatsoever on the activities of defendant No.1 and in view of the reliefs sought in the suit the defendant Nos.3 and 4 are neither the necessary nor proper parties. -

A New a W Akening with the Sun Tha T Brings Light To

jplcorp .in designed at www. 2216163 2216162 2216161 0512 telephone 208005 Kanpur printed at www.constantdesign.com 2 Sarvodaya Nagar Sarvodaya 2 [email protected] Building Jagran Jagran Prakashan Limited Prakashan Jagran A NEW AWAKENING WITH THE SUN THAT BRINGS LIGHT TO THE WORLD ANNUAL REPORT JAGRAN PRAKASHAN LIMITED 09/10 Mr. Mahendra Mohan Gupta Chairman and Managing Director Mr. Sanjay Gupta Whole Time Director and CEO Mr. Dhirendra Mohan Gupta Whole Time Director Mr. Sunil Gupta to the company 7 Whole Time Director Central Bank of India notice Mr. Shailesh Gupta Bank of Baroda Whole Time Director ICICI Bank Limited Mr. Bharatji Agrawal bankers Allahabad Bank 13 Mr. Devendra Mohan Gupta State Bank of India directors’ report Mr. Gavin K.O’Reilly Union Bank of India Mr. Kishore Biyani Oriental Bank of Commerce Mr. Naresh Mohan 19 Mr. Rahul Gupta report on corporate governance Alternate Director to Mr. Gavin K.O’Reilly Mr. Rajendra Kr. Jhunjhunwala Mr. Rashid Mirza Mr. Shailendra Mohan Gupta 35 Mr. Shashidhar Narain Sinha management discussion and analysis Mr. Vijay Tandon board of directors Mr. Vikram Bakshi Jagran Building 45 2 Sarvodaya Nagar Kanpur-208005 persons constituting group registered office committee 47 Mr. Vijay Tandon compliance certificate on corpoarte governance Chairman audit Mr. Gavin K. O’Reilly Mr. Kishore Biyani 49 Mr. Naresh Mohan auditor’s report Mr. Rajendra Kr. Jhunjhunwala company secretary 53 and compliance officer balance sheet Mr. Amit Jaiswal shareholders / investors 57 grievance committee profit and loss account Mr. Bharatji Agrawal Chairman 09/10 Mr. Rashid Mirza 61 Mr. Sanjay Gupta cash flow statement Mr. -

Earnings Release for Q2fy20 "

ft THE WORLD'S LARGEST READ DAILY Jagran November 13,2019 1) Manager-CRD, BSE Ltd., Re: Jagran Prakashan Limited Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Scrip Code: 532705 Dalal Street, ISINNo.: INE199G01027 Mumbai-400001 2) Listing Manager, National Stock Exchange of India Ltd., Re: Jagran Prakashan Limited 'Exchange Plaza' Symbol: JAGRAN Bandra Kurla Complex, ISIN No.: INE199G01027 Bandra (E), Mumbai-400 051 Dear Sir/Ma'am, Sub.: Intimation to Stock Exchange - Press Release in connection with Un-audited Standalone and Consolidated Financial Results for the quarter / half-year ended September 30, 2019. Please find enclosed herewith the copy of Press Release in connection with Un-audited Standalone and Consolidated Financial Results for the quarter / half-year ended September 30, 2019. Kindly take the above on your record. Thanking You, For Jagran Prakashan Limited (AMIT JAISWAL) Company Secretary & Compliance Officer Membership No.: F5863 Encl.: As Above PRINT OUT OF HOME Jagran Prakashan Ltd CIN: L22219UP1975PlC004147 ACTIVATION Jagran Building, 2 Sarvodaya Nagar, Kanpur 208 005 E-mail: [email protected] MOBILE T +91 512 3941300 F +91 512 2298040, 2216972 Registered Office www.jagran.com www.jplcorp.in 2, Sarvodaya Nagar, Kanpur 208 005, Uttar Pradesh, India ONLINE Press Release Jagran EARNINGS RELEASE FOR Q2FY20 " Consolidated Operating Revenue Rs. 514.50 crores Consolidated Operating Profit Rs 90.12 crores Consolidated PAT Rs 125.78 crores New Delhi, November 13, 2019; Jagran Prakashan Limited (JPL) (BSE SCRIP ID: 532705; NSE SYMBOL: JAGRAN), publishers of 'Dainik Jagran', India's largest read newspaper (Source: IRS2019 Q2), has reported the quarterly results for the quarter ended 30th September 2019. -

CM to Unesco

millenniumpost.in RNI NO.: WBENG/2015/65962 SUNDAY millenniumPUBLISHED FROM DELHI & KOLKATA VOL. 3, ISSUE 171 | Sunday, 25 June, 2017 | Kolkata | Pages 16 | Rs 3.00 post NO HALF TRUTHS CITY PAGE 3 NATION PAGE 4 SPORT PAGE 15 BJP’S BLOOD DONATION CAMP LURES J&K LYNCHING: 5 PERSONS FIRING ON ALL DONORS WITH LOTTERY FOR GIFTS ARRESTED, SP SHUNTED OUT CYLINDERS Quick News44 NET AGE: I-T notice Monsoon session from Thank you so much for the will no more mean July 17 to August 11 ‘dealing’ with tax man OUR CORRESPONDENT recognition: CM to Unesco NEW DELHI: The Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT), the policy-making body of the World hails Mamata, Bengal for Kanyashree achievement income tax (I-T) department, TARUN GOSWAMI which wants to curb complaints of harassment and corrup- KOLKATA: Chief minister Mamata tion from honest tax-payers, financial year,” the CBDT order Banerjee announced on Saturday has notified revised income said. Each of the three, one-page that the West Bengal government tax (I-T) scrutiny notices that notices, will bear the name of NEW DELHI: The Monsoon Session of Par- will celebrate the achievement of will allow taxpayers to conduct the assessing officer, his or her liament will commence from July 17, the day the Kanyashree Prakalpa, which their business with the taxman designation, telephone and fax voting for the presidential election is slated to won the first prize in the United over the Internet without need- number and now, their email take place. The Cabinet Committee on Parlia- Nations (UN) Public Service Award ing to visit the I-T office.