Brief Draft 23

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advice on Finding a Well Reared Staffordshire Bull Terrier Puppy

ADVICE ON FINDING A WELL REARED STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER PUPPY We hope this booklet will offer you some helpful advice. Looking for that perfect new member to add to your family can be a daunting task - this covers everything you need to know to get you started on the right track. Advice on finding a well reared Staffordshire Bull Terrier Puppy. It can be an exciting time looking for that new puppy to add to your family. You know you definitely want one that is a happy, healthy bundle of joy and so you should. You must remember there are many important things to consider as well and it is hoped this will help you to understand the correct way to go about finding a happy, healthy and well reared Staffordshire Bull Terrier puppy. First things first, are you ready for a dog? Before buying a puppy or a dog, ask yourself: Most importantly, is a Stafford the right breed for me and/or my family? – Contact your local Breed Club Secretary to find out any local meeting places, shows, events or recommended breeders. Can I afford to have a dog, taking into account not only the initial cost of purchasing the dog, but also the on-going expenses such as food, veterinary fees and canine insurance? Can I make a lifelong commitment to a dog? - A Stafford’s average life span is 12 years. Is my home big enough to house a Stafford? – Or more importantly is my garden secure enough? Do I really want to exercise a dog every day? – Staffords can become very naughty and destructive if they get bored or feel they are not getting the time they deserve. -

Dog Breeds Impounded in Fy16

DOG BREEDS IMPOUNDED IN FY16 AFFENPINSCHER 4 AFGHAN HOUND 1 AIREDALE TERR 2 AKITA 21 ALASK KLEE KAI 1 ALASK MALAMUTE 6 AM PIT BULL TER 166 AMER BULLDOG 150 AMER ESKIMO 12 AMER FOXHOUND 12 AMERICAN STAFF 52 ANATOL SHEPHERD 11 AUST CATTLE DOG 47 AUST KELPIE 1 AUST SHEPHERD 35 AUST TERRIER 4 BASENJI 12 BASSET HOUND 21 BEAGLE 107 BELG MALINOIS 21 BERNESE MTN DOG 3 BICHON FRISE 26 BLACK MOUTH CUR 23 BLACK/TAN HOUND 8 BLOODHOUND 8 BLUETICK HOUND 10 BORDER COLLIE 55 BORDER TERRIER 22 BOSTON TERRIER 30 BOXER 183 BOYKIN SPAN 1 BRITTANY 3 BRUSS GRIFFON 10 BULL TERR MIN 1 BULL TERRIER 20 BULLDOG 22 BULLMASTIFF 30 CAIRN TERRIER 55 CANAAN DOG 1 CANE CORSO 3 CATAHOULA 26 CAVALIER SPAN 2 CHESA BAY RETR 1 CHIHUAHUA LH 61 CHIHUAHUA SH 673 CHINESE CRESTED 4 CHINESE SHARPEI 38 CHOW CHOW 93 COCKER SPAN 61 COLLIE ROUGH 6 COLLIE SMOOTH 15 COTON DE TULEAR 2 DACHSHUND LH 8 DACHSHUND MIN 38 DACHSHUND STD 57 DACHSHUND WH 10 DALMATIAN 6 DANDIE DINMONT 1 DOBERMAN PINSCH 47 DOGO ARGENTINO 4 DOGUE DE BORDX 1 ENG BULLDOG 30 ENG COCKER SPAN 1 ENG FOXHOUND 5 ENG POINTER 1 ENG SPRNGR SPAN 2 FIELD SPANIEL 2 FINNISH SPITZ 3 FLAT COAT RETR 1 FOX TERR SMOOTH 10 FOX TERR WIRE 7 GERM SH POINT 11 GERM SHEPHERD 329 GLEN OF IMALL 1 GOLDEN RETR 56 GORDON SETTER 1 GR SWISS MTN 1 GREAT DANE 23 GREAT PYRENEES 6 GREYHOUND 8 HARRIER 7 HAVANESE 7 IBIZAN HOUND 2 IRISH SETTER 2 IRISH TERRIER 3 IRISH WOLFHOUND 1 ITAL GREYHOUND 9 JACK RUSS TERR 97 JAPANESE CHIN 4 JINDO 3 KEESHOND 1 LABRADOR RETR 845 LAKELAND TERR 18 LHASA APSO 61 MALTESE 81 MANCHESTER TERR 11 MASTIFF 37 MIN PINSCHER 81 NEWFOUNDLAND -

Table & Ramp Breeds

Judging Operations Department PO Box 900062 Raleigh, NC 27675-9062 919-816-3570 [email protected] www.akc.org TABLE BREEDS SPORTING NON-SPORTING COCKER SPANIEL ALL AMERICAN ESKIMOS ENGLISH COCKER SPANIEL BICHON FRISE NEDERLANDSE KOOIKERHONDJE BOSTON TERRIER COTON DE TULEAR FRENCH BULLDOG HOUNDS LHASA APSO BASENJI LOWCHEN ALL BEAGLES MINIATURE POODLE PETIT BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN (or Ground) NORWEGIAN LUNDEHUND ALL DACHSHUNDS SCHIPPERKE PORTUGUSE PODENGO PEQUENO SHIBA INU WHIPPET (or Ground or Ramp) TIBETAN SPANIEL TIBETAN TERRIER XOLOITZCUINTLI (Toy and Miniatures) WORKING- NO WORKING BREEDS ON TABLE HERDING CARDIGAN WELSH CORGI TERRIERS MINIATURE AMERICAN SHEPHERD ALL TERRIERS on TABLE, EXCEPT those noted below PEMBROKE WELSH CORGI examined on the GROUND: PULI AIREDALE TERRIER PUMI AMERICAN STAFFORDSHIRE (or Ramp) PYRENEAN SHEPHERD BULL TERRIER SHETLAND SHEEPDOG IRISH TERRIERS (or Ramp) SWEDISH VALLHUND MINI BULL TERRIER (or Table or Ramp) KERRY BLUE TERRIER (or Ramp) FSS/MISCELLANEOUS BREEDS SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER (or Ramp) DANISH-SWEDISH FARMDOG STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER (or Ramp) LANCASHIRE HEELER MUDI (or Ramp) PERUVIAN INCA ORCHID (Small and Medium) TOY - ALL TOY BREEDS ON TABLE RUSSIAN TOY TEDDY ROOSEVELT TERRIER RAMP OPTIONAL BREEDS At the discretion of the judge through all levels of competition including group and Best in Show judging. AMERICAN WATER SPANIEL STANDARD SCHNAUZERS ENTLEBUCHER MOUNTAIN DOG BOYKIN SPANIEL AMERICAN STAFFORDSHIRE FINNISH LAPPHUND ENGLISH SPRINGER SPANIEL IRISH TERRIERS ICELANDIC SHEEPDOGS FIELD SPANIEL KERRY BLUE TERRIER NORWEGIAN BUHUND LAGOTTO ROMAGNOLO MINI BULL TERRIER (Ground/Table) POLISH LOWLAND SHEEPDOG NS DUCK TOLLING RETRIEVER SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER SPANISH WATER DOG WELSH SPRINGER SPANIEL STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER MUDI (Misc.) GRAND BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN FINNISH SPITZ NORRBOTTENSPETS (Misc.) WHIPPET (Ground/Table) BREEDS THAT MUST BE JUDGED ON RAMP Applies to all conformation competition associated with AKC conformation dog shows or at any event at which an AKC conformation title may be earned. -

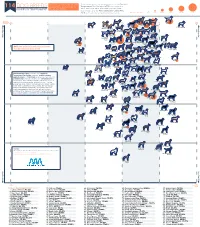

Ranked by Temperament

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

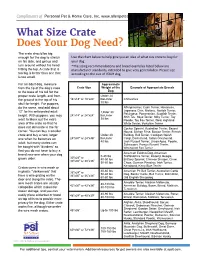

What Size Crate Does Your Dog Need?

Compliments of What Size Crate Does Your Dog Need? The crate should be big enough for the dog to stretch Use the chart below to help give you an idea of what size crate to buy for on his side, and get up and your dog. turn around without his head *The sizing recommendations and breed examples listed below are hitting the top. A crate that is manufacturer standards, intended to give very general idea. Please size too big is better than one that according to the size of YOUR dog. is too small. For an adult dog, measure Approximate from the tip of the dog’s nose Crate Size Weight of the Example of Appropriate Breeds to the base of his tail for the Dog proper crate length, and from Under 24 the ground to the top of his 18"x18" or 18"x24" lbsUnder Chihuahua skull for height. For puppies, 30 lbs do the same, and add about Affenpinscher, Cairn Terrier, Havanese, Japanese Chin, Maltese, Norfolk Terrier, 12” for his anticipated adult Under 30 Pekingese, Pomeranian, Scottish Terrier, 24”x18” or 24”x24” lbsUnder height. With puppies, you may Shih Tzu, Skye Terrier, Silky Terrier, Toy 38 lbs want to block out the extra Poodle, Toy Fox Terrier, West Highland area of the crate so that he White Terrier, Yorkshire Terrier does not eliminate in the far Cocker Spaniel, Australian Terrier, Basset corner. You can buy a smaller Hound, Bichon Frise, Boston Terrier, French crate and buy a new, larger Under 40 Bulldog, Bull Terrier, Cardigan Welsh one when he becomes an 24"x30" or 24"x36" lbsUnder Corgi, Dachshund, Italian Greyhound, adult, but many crates can 40 lbs Jack Russell Terrier, Lhasa Apso, Poodle, Schnauzer, Parson Russell Terrier, be bought with “dividers” so Wirehaired Fox Terrier that you do not have to buy a American Eskimo Dog, American brand new one when your dog 0-40 lbs Staffordshire Terrier, Basenji, Beagle, 30"x24" or grows older. -

ASPCA - Virtual Pet Behaviorist - the Truth About Pit Bulls

ASPCA - Virtual Pet Behaviorist - The Truth About Pit Bulls http://www.aspcabehavior.org/articles/193/The-Truth-About-Pit-Bulls.aspx Register Login Sitemap Home > Pet Care > Virtual Pet Behaviorist Animal Poison Control Virtual Pet Behaviorist Center Back to List Ask the Experts Virtual Pet Behaviorist Pet Care Tips The Truth About Pit Bulls Print this Page What Is a Pit Bull? Pet Loss There’s a great deal of confusion associated with the label “pit bull.” This isn’t surprising Pet Care Videos because the term doesn’t describe a single breed of dog. Depending on whom you ask, it can refer to just a couple of breeds or to as many as five—and all mixes of these breeds. Kids and Pets The most narrow and perhaps most accurate definition of the term “pit bull” refers to just two breeds: the American Pit Bull Terrier (APBT) and the American Staffordshire Terrier Free and Low-Cost (AmStaff). Some people include the Bull Terrier, the Staffordshire Bull Terrier and the What type of pet do you own? Spay/Neuter Database American Bulldog in this group because these breeds share similar head shapes and body Select... types. However, they are distinct from the APBT and the AmStaff. Disaster Preparedness What is your pet doing? Because of the vagueness of the “pit bull” label, many people may have trouble Pet Food Recalls recognizing a pit bull when they see one. Multiple breeds are commonly mistaken for pit bulls, including the Boxer, the Presa Canario, the Cane Corso, the Dogo Argentino, the Tosa Inu, the Bullmastiff, the Dogue de Bordeaux, the Alapaha Blue Blood Bulldog and the Olde English Bulldogge. -

What Makes It a Miniature Bull Terrier?

What makes it a Miniature Bull Terrier? By Tracey Butchart After reading the Breed Standard for the Bull Terrier and the Miniature Bull Terrier, you would be forgiven for thinking that the latter is just a small version of the former. In reality however, the Mini, as it is affectionately known, is genetically distinct from its bigger relative, unlike, for example, the Poodles and Dachshunds with their different size varieties. It was in the 1860s that James Hinks of Birmingham created the all-white Bull Terrier, which was noticeably different from the motley bunch of “Bull-and-Terriers” that had been around decades and who were so successful in the dog fighting pits of the time. This new “Bull Terrier” was elevated from its dark and violent past emerging as a gentleman’s companion. In fact, according to Hinks’ biographer, Kevin Kane, it was bred as a fashion accessory for the new middle classes, albeit one which symbolised power and masculinity. Despite the fact that they all had a distinctive white coat, there was significant variation in size among early Bull Terriers. At the famous International Show of Dogs at Islington in 1864, the Bull Terrier entries were divided into different classes determined by size. There were Bull Terriers under 10lbs and Bull Terriers over 10lbs. This weight limit was adjusted to 15lbs three years later and then to 25lbs another 7 years on. Clearly, the larger Bull Terriers were preferred. At the turn of the century there were actually three sizes: large (Standard Bull Terriers); medium (Miniature Bull Terriers) and small (Toy Bull Terriers). -

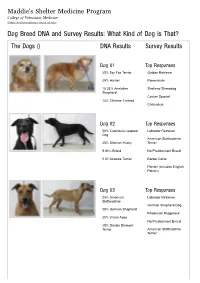

Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog Is That? the Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results

Maddie's Shelter Medicine Program College of Veterinary Medicine (https://sheltermedicine.vetmed.ufl.edu) Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog is That? The Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results Dog 01 Top Responses 25% Toy Fox Terrier Golden Retriever 25% Harrier Pomeranian 15.33% Anatolian Shetland Sheepdog Shepherd Cocker Spaniel 14% Chinese Crested Chihuahua Dog 02 Top Responses 50% Catahoula Leopard Labrador Retriever Dog American Staffordshire 25% Siberian Husky Terrier 9.94% Briard No Predominant Breed 5.07 Airedale Terrier Border Collie Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 03 Top Responses 25% American Labrador Retriever Staffordshire German Shepherd Dog 25% German Shepherd Rhodesian Ridgeback 25% Lhasa Apso No Predominant Breed 25% Dandie Dinmont Terrier American Staffordshire Terrier Dog 04 Top Responses 25% Border Collie Wheaten Terrier, Soft Coated 25% Tibetan Spaniel Bearded Collie 12.02% Catahoula Leopard Dog Briard 9.28% Shiba Inu Cairn Terrier Tibetan Terrier Dog 05 Top Responses 25% Miniature Pinscher Australian Cattle Dog 25% Great Pyrenees German Shorthaired Pointer 10.79% Afghan Hound Pointer (includes English 10.09% Nova Scotia Duck Pointer) Tolling Retriever Border Collie No Predominant Breed Dog 06 Top Responses 50% American Foxhound Beagle 50% Beagle Foxhound (including American, English, Treeing Walker Coonhound) Harrier Black and Tan Coonhound Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 07 Top Responses 25% Irish Water Spaniel Labrador Retriever 25% Siberian Husky American Staffordshire Terrier 25% Boston -

Staffordshire Bull Terriers and Staffie-Crosses

• Staffies love children, making them an who will be happy to help after they’ve ideal family pet. They can be a bit too left our home for yours. much for very little children as they are so energetic and strong, so this should be Buying a Staffordshire Bull Terrier: considered when looking to get a Staffie • If you are going to buy a pup from a or Staffie-cross. Staffie breeder, you can expect to pay around £300-£500. Staffordshire What to do if you want to welcome a Staffordshire Bull • Make sure that you go to a reputable Bull Terriers and breeder and ask to see the pups with Terrier into your life... their mother before you make any decisions about buying one. Staffie-crosses Choosing to get a dog is a very big decision, especially if that dog is likely to be a • A good dog breeder will always get Staffie. You must think very carefully about their pups checked over by a vet and whether you have the time and energy to have them vaccinated, wormed & given take one on as, despite the rewards, they flea-treatment before they go to their do require a huge commitment from their new home. Ask for vaccination cards owners in order to lead happy lives. or vet documents to make sure this has been done. If you’re set on a Staffie, you have two main options for getting one: Be a responsible owner and neuter Rehoming from a rescue organisation: your dog – it’s simply the best choice • If you want to rehome a Staffie from a for you and your pet. -

Baskerville Ultra Muzzle Breed Guide. Sizes Are Available in 1 - 6 and Are for Typical Adult Dogs & Bitches

Baskerville Ultra Muzzle Breed Guide. Sizes are available in 1 - 6 and are for typical adult dogs & bitches. Juveniles may need a size smaller. ‡ = not recommended. The number next to the breeds below is the recommended size. Boston Terrier ‡ Bulldog ‡ King Charles Spaniel ‡ Lhasa Apso ‡ Pekingese ‡ Pug ‡ St Bernard ‡ Shih Tzu ‡ Afghan Hound 5 Airedale 5 Alaskan Malamute 5 American Cocker 2 American Staffordshire 6 Australian Cattle Dog 3 Australian Shepherd 3 Basenji 2 Basset Hound 5 Beagle 3 Bearded Collie 3 Bedlington Terrier 2 Belgian Shepherd 5 Bernese MD 5 Bichon Frisé 1 Border Collie 3 Border Terrier 2 Borzoi 5 Bouvier 6 Boxer 6 Briard 5 Brittany Spaniel 5 Buhund 2 Bull Mastiff 6 Bull Terrier 5 Cairn Terrier 2 Cavalier Spaniel 2 Chow Chow 5 Chesapeake Bay Retriever 5 Cocker (English) 3 Corgi 3 Dachshund Miniature 1 Dachshund Standard 1 Dalmatian 4 Dobermann 5 Elkhound 4 English Setter 5 Flat Coated Retriever 5 Foxhound 5 Fox Terrier 2 German Shepherd 5 Golden Retriever 5 Gordon Setter 5 Great Dane 6 Greyhound 5 Hungarian Vizsla 3 Irish Setter 5 Irish Water Spaniel 3 Irish Wolfhound 6 Jack Russell 2 Japanese Akita 6 Keeshond 3 Kerry Blue Terrier 4 Labrador Retriever 5 Lakeland Terrier 2 Lurcher 5 Maltese Terrier 1 Maremma Sheepdog 5 Mastiff 6 Munsterlander 5 Newfoundland 6 Norfolk/Norwich Terrier 1 Old English Sheepdog 5 Papillon N/A Pharaoh Hound 5 Pit Bull 6 Pointers 4 Poodle Toy 1 Poodle Standard 3 Pyrenean MD 6 Ridgeback 5 Rottweiler 6 Rough Collie 3 Saluki 3 Samoyed 4 Schnauzer Miniature 2 Schnauzer 3 Schnauzer Giant 6 Scottish Terrier 3 Sheltie 2 Shiba Inu 2 Siberian Husky 5 Soft Coated Wheaten 4 Springer Spaniel 4 Staff Bull Terrier 6 Weimaraner 5 Welsh Terrier 3 West Highland White 2 Whippet 2 Yorkshire Terrier 1 . -

Anglo-American Blood Sports, 1776-1889: a Study of Changing Morals

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1974 Anglo-American blood sports, 1776-1889: a study of changing morals. Jack William Berryman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Berryman, Jack William, "Anglo-American blood sports, 1776-1889: a study of changing morals." (1974). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1326. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1326 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLO-AMERICAN BLOOD SPORTS, I776-I8891 A STUDY OF CHANGING MORALS A Thesis Presented By Jack William Berryman Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS April, 197^ Department of History » ii ANGLO-AMERICAN BLOOD SPORTS, 1776-1889 A STUDY OF CHANGING MORALS A Thesis By Jack V/illiam Berryman Approved as to style and content by« Professor Robert McNeal (Head of Department) Professor Leonard Richards (Member) ^ Professor Paul Boyer (I'/iember) Professor Mario DePillis (Chairman) April, 197^ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Upon concluding the following thesis, the many im- portant contributions of individuals other than myself loomed large in my mind. Without the assistance of others the project would never have been completed, I am greatly indebted to Professor Guy Lewis of the Department of Physical Education at the University of Massachusetts who first aroused my interest in studying sport history and continued to motivate me to seek the an- swers why. -

Should I Share My Apartment with A

������� ����������� ���������� ����������� ��������������������� ��������������������������� Contents Responsibility Considerations Dogs with lower exercise requirements More information about the breeds Ideas for keeping your dog entertained The ‘pet friendly’ apartment Prior to getting a dog References Contents Responsibility Dogs offer wonderful companionship, but that comes Responsibility with responsibility. A dog can live from 8–18+ years (depending on the breed). It is the owner’s responsibility Considerations to exercise, train and socialise their dog. This is a huge time commitment that does not take holidays! Dogs with lower exercise requirements Dogs are social animals and are not suited to being left alone for long periods. Getting a second dog to keep More information about the breeds the other dog company is not a logical solution – you could make the problem twice as bad for Ideas for keeping your dog entertained yourself and your neighbours. Most of the common dog problems (barking, The ‘pet friendly’ apartment digging, chewing, escaping, destructiveness and boisterous behaviour) can be Prior to getting a dog prevented if you walk your dog morning and evening, play with your dog and References provide it with some basic training. If you meet your dog’s mental and physical needs before you leave for work, the dog is far more likely to settle and not get into trouble due to boredom. Considerations If you live in an apartment and are thinking of getting a dog, the most important considerations are: ª How energetic is the breed of dog. ª How old is the dog. Puppies are a huge time The lower the energy level, the easier to investment, so consider the age of the dog as manage in a smaller area.