(Western Cape Division, Cape Town) Case No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measuring the Effects of Political Reservations Thinking About Measurement and Outcomes

J-PAL Executive Education Course in Evaluating Social Programmes Course Material University of Cape Town 23 – 27 January 2012 J-PAL Executive Education Course in Evaluating Social Programmes Table of Contents Programme ................................................................................................................................ 3 Maps and Directions .................................................................................................................. 5 Course Objectives....................................................................................................................... 7 J-PAL Lecturers ......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Participants .................................................................................................................... 11 Group Assignment .................................................................................................................. 12 Case Studies ............................................................................................................................. 13 Case Study 2: Learn to Read Evaluations ............................................................................... 18 Case Study 3: Extra Teacher Program .................................................................................... 27 Case Study 4: Deworming in Kenya ....................................................................................... 31 Exercises -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

Sunsquare City Bowl Fact Sheet 8.Indd

Opens September 2017 Lobby Group and conference fact sheet Standard room A city hotel for the new generation With so much to do and see in Cape Town, you need to stay somewhere central. Situated on the corner of Buitengracht and Strand Street, the bustling location of SunSquare Cape Town City Bowl inspires visitors to explore the hip surroundings and get to know the city. The bedrooms The hotel’s 202 rooms are divided into spacious standard rooms with queen The Deck Bar size beds, twin rooms each with 2 double beds, 5 executive rooms, 2 suites and 2 wheelchair accessible rooms. Local attractions Hotel services Long Street - 200 m • Rooftop pool with panoramic views of the V&A Waterfront and Signal Hill CTICC - 1 km • Fitness centre on the top fl oor with views of Table Mountain Artscape Theatre - 1 km • 500 MB free high-speed WiFi per room, per day V&A Waterfront - 2 km • Rewards cardholders get 2GB free WiFi per room, per day Cape Town Stadium - 2 km Two Oceans Aquarium - 2 km Table Mountain Cable Way - 5 km Other facilities • Vigour & Verve restaurant • Transfer services • Rooftop Deck Bar and Lounge • Shuttle service (on request) Contact us • Secure basement parking • Car rental 23 Buitengracht Street, • Airport handling service • Dry cleaning Cape Town City Centre, 8000 Telephone: +27 21 492 0404 Meeting spaces Email: capetown.reservations@ 5 conference rooms in total catering for up to 140 delegates. The venues can be tsogosun.com confi gured to host a range of occasions like intimate boardroom meetings, cocktail GPS Coordinates: -33.919122 S / 18.419020 E functions, workshops, seminars, training sessions, conferences as well as product launches. -

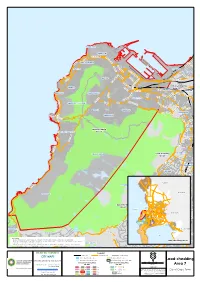

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

The Best Address in Cape Town

THE BEST ADDRESS IN CAPE TOWN The Table Bay, opened in May 1997 by iconic former South African president, Nelson Mandela, is situated on the historic Victoria & Alfred Waterfront. Perfectly positioned against the exquisite backdrop of Table Mountain and the Atlantic Ocean, providing a gateway to Cape Town’s most popular allures. SUN INTERNATIONAL CREATING LASTING MEMORIES THE ESSENCE OF THE ENCHANTING CAPE A stay at The Table Bay affords guests’ once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to be graced by the synergy of two oceans, witness South Africa’s floral kingdom, take a trip to an island symbolic of our history, explore a natural wonder of the world and be captivated by the sheer beauty of the Cape’s breathtaking sceneries or majestic mammals. THE LEGEND OF OSCAR In pride of place at the entrance to The Table Bay, a sun-gold statue of a seal proudly welcomes guests. At first glance, the impressive seal sculpture is a fitting mascot – Cape Fur Seals are an integral part of harbour life at the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront, and seal-watching is an amusing pastime. But Oscar the Seal wasn’t just another playful marine pup gambolling along the quayside. Beneath the statue erected in his honour, an inscription reads: “Oscar” the Cape Fur Seal. The original protector and guardian of The Table Bay. Oscar’s story is the stuff of legends, and inextricably intertwined with the history of the hotel. Guests can admire this iconic statue whilst enjoying lunch and a cocktail on Oscar’s Terrace. SUN INTERNATIONAL CREATING LASTING MEMORIES DIVE INTO THE FINER DETAILS The luxurious oxygenated and heated hotel pool is surrounded by a mahogany pool deck with chaises longues, where guests can relax after a rejuvenating swim or a dip in the Jacuzzi. -

In the High Court of South Africa Western Cape Division, Cape Town

SAFLII Note: Certain personal/private details of parties or witnesses have been redacted from this document in compliance with the law and SAFLII Policy IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA WESTERN CAPE DIVISION, CAPE TOWN REPORTABLE CASE NO: A 276/2017 In the matter between: FREDERICK WESTERHUIS First Appellant CATHERINE WESTERHUIS Second Appellant and JAN LAMBERTUS WESTERHUIS First Respondent JAN LAMBERTUS WESTERHUIS N.O. (In his capacity as the Executor in the Estate of the late John Westerhuis) Second Respondent DERICK ALEXANDER WESTERHUIS N.O. (In his capacity as the Executor in the Estate of the late John Westerhuis) Third Respondent JAN LAMBERTUS WESTERHUIS N.O. (In his capacity as the Executor in the 2 Estate of the late Hendrikus Westerhuis) Fourth Respondent PATRICIA WESTERHUIS Fifth Respondent MARELIZE VAN DER MESCHT Sixth Respondent Coram: Erasmus, Gamble and Parker JJ. Date of Hearing: 20 April 2018. Date of Judgment: 27 June 2018. JUDGMENT DELIVERED ON WEDNESDAY 27 JUNE 2018 ____________________________________________________________________ GAMBLE, J: INTRODUCTION [1] In the aftermath of the Second World War there was a large migration of European refugees to various parts of the world, including South Africa. Amongst that number were Mr. Hendrikus Westerhuis and his wife, Trish, her sister Ms. Jannetje Haasnoot and her husband who was known as “Hug” Haasnoot. The Westerhuis and Haasnoot families first shared a communal home in the Cape Town suburb of Claremont and later moved to Vredehoek on the slopes of Devil’s Peak where they lived in adjacent houses. The Haasnoots stayed at […]3 V. Avenue and the Westerhuis’ at number […]5. -

Your Guide to Myciti

Denne West MyCiTi ROUTES Valid from 29 November 2019 - 12 january 2020 Dassenberg Dr Klinker St Denne East Afrikaner St Frans Rd Lord Caledon Trunk routes Main Rd 234 Goedverwacht T01 Dunoon – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront Sand St Gousblom Ave T02 Atlantis – Table View – Civic Centre Enon St Enon St Enon Paradise Goedverwacht 246 Crown Main Rd T03 Atlantis – Melkbosstrand – Table View – Century City Palm Ln Paradise Ln Johannes Frans WEEKEND/PUBLIC HOLIDAY SERVICE PM Louw T04 Dunoon – Omuramba – Century City 7 DECEMBER 2019 – 5 JANUARY 2020 MAMRE Poeit Rd (EXCEPT CHRISTMAS DAY) 234 246 Silverstream A01 Airport – Civic Centre Silwerstroomstrand Silverstream Rd 247 PELLA N Silwerstroom Gate Mamre Rd Direct routes YOUR GUIDE TO MYCITI Pella North Dassenberg Dr 235 235 Pella Central * D01 Khayelitsha East – Civic Centre Pella Rd Pella South West Coast Rd * D02 Khayelitsha West – Civic Centre R307 Mauritius Atlantis Cemetery R27 Lisboa * D03 Mitchells Plain East – Civic Centre MyCiTi is Cape Town’s safe, reliable, convenient bus system. Tsitsikamma Brenton Knysna 233 Magnet 236 Kehrweider * D04 Kapteinsklip – Mitchells Plain Town Centre – Civic Centre 245 Insiswa Hermes Sparrebos Newlands D05 Dunoon – Parklands – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront SAXONSEAGoede Hoop Saxonsea Deerlodge Montezuma Buses operate up to 18 hours a day. You need a myconnect card, Clinic Montreal Dr Kolgha 245 246 D08 Dunoon – Montague Gardens – Century City Montreal Lagan SHERWOOD Grosvenor Clearwater Malvern Castlehill Valleyfield Fernande North Brutus -

Fact Sheet – Cape Town, South Africa Information Sourced at Population About 3.5-Million People Li

Fact Sheet – Cape Town, South Africa Information sourced at http://www.capetown.travel/ Population About 3.5-million people live in Cape Town, South Africa's second most-populated city. Time Cape Town lies in the GMT +2 time zone and does not have daylight saving time. Area South Africa is a large country, of 2 455km2(948mi2). Government Mayor of Cape Town: Patricia de Lille (Democratic Alliance) Premier of the Western Cape: Helen Zille (Democratic Alliance) Cape Town is the legislative capital of South Africa South Africa's Parliament sits in Cape Town History Cape Town was officially founded in 1652 when Jan van Riebeeck of the Dutch East India Company based in The Netherlands arrived to set up a halfway point for ships travelling to the East. Portuguese explorers arrived in the Cape in the 15th Century and Khoisan people inhabited the area prior to European arrival. Electricity South Africa operates on a 220/230V AC system and plugs have three round prongs. Telephone Country code: 0027 City code: 021 Entrance Visa requirements depend on nationality, but all foreign visitors are required to hold a valid passport. South Africa requires a valid yellow fever certificate from all foreign visitors and citizens over 1 year of age travelling from an infected area or having been in transit through infected areas. For visa requirements, please contact your nearest South African diplomatic mission. Fast facts Cape Town is the capital of the Western Cape. The city‟s motto is “Spes Bona”, which is Latin for “good hope”. Cape Town is twinned with London, Buenos Aires, Nice, San Francisco and several other international cities. -

Cape Town 2021 Touring

CAPE TOWN 2021 TOURING Go Your Way Touring 2 Pre-Booked Private Touring Peninsula Tour 3 Peninsula Tour with Sea Kayaking 13 Winelands Tour 4 Cape Canopy Tour 13 Hiking Table Mountain Park 14 Suggested Touring (Flexi) Connoisseur's Winelands 15 City, Table Mountain & Kirstenbosch 5 Cycling in the Winelands & visit to Franschhoek 15 Cultural Tour - Robben Island & Kayalicha Township 6 Fynbos Trail Tour 16 Jewish Cultural & Table Mountain 7 Robben Island Tour 16 Constantia Winelands 7 Cape Malay Cultural Cooking Experience 17 Grand Slam Peninsula & Winelands 8 “Cape Town Eats” City Walking Tour 17 West Coast Tour 8 Cultural Exploration with Uthando 18 Hermanus Tour 9 Cape Grace Art & Antique Tour 18 Shopping & Markets 9 Group Scheduled Tours Whale Watching & Shark Diving Tours Group Peninsula Tour 19 Dyer Island 'Big 5' Boat Ride incl. Whale Watching 10 Group Winelands Tour 19 Gansbaai Shark Diving Tour 11 Group City Tour 19 False Bay Shark Eco Charter 12 Touring with Families Family Peninsula Tour 20 Family Fun with Animals 20 Featured Specialist Guides 21 Cape Town Touring Trip Reports 24 1 GO YOUR WAY – FULL DAY OR HALF DAY We recommend our “Go Your Way” touring with a private guide and vehicle and then customizing your day using the suggested tour ideas. Cape Town is one of Africa’s most beautiful cities! Explore all that it offers with your own personalized adventure with amazing value that allows a day of touring to be more flexible. RATES FOR FULL DAY or HALF DAY– GO YOUR WAY Enjoy the use of a vehicle and guide either for a half day or a full day to take you where and when you want to go. -

Water Quality of Rivers and Open Waterbodies in the City of Cape Town

WATER QUALITY OF RIVERS AND OPEN WATERBODIES IN THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN: STATUS AND HISTORICAL TRENDS, WITH A FOCUS ON THE PERIOD APRIL 2015 TO MARCH 2020 FINAL AUGUST 2020 TECHNICAL REPORT PREPARED BY Liz Day Dean Ollis Tumisho Ngobela Nick Rivers-Moore City of Cape Town Inland Water Quality Technical Report FOREWORD The City has committed itself, in its new Water Strategy, to become a Water Sensitive City by 2040. A Water Sensitive City is a city where rivers, canals and streams are accessible, inclusive and safe to use. The City is releasing this Technical Report on the quality of water in our watercourses, to promote transparency and as a spur to action to achieve this goal. While some of our 20 river catchments are in a relatively good /near natural state, there are six catchments with particularly serious challenges. Overall, the data show that we have a long way to go to achieve our goal. Where this report has revealed areas of concern, the City commits to full transparency around possible causes which need to be addressed from within the organization, however we request that residents always keep in mind the role they have to play, and take on their share of responsibility for ensuring the next report paints a more favourable picture. It is in all of our interests. On the City’s side, efforts to address water pollution are being intensified. We have drastically stepped up the upgrading of wastewater treatment works, assisted by loan funding, and are constantly working to reduce sewer overflows, improve solid waste collection/cleansing, and identify and prosecute offenders. -

Robben Island Histories, Identities and Futures

Robben Island Histories, identities and futures The past, present and future meaning of place Brett Seymour A paper submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of B.A. (Hons) in History The University of Sydney 2012 Introduction The inclusion of place as a subject of historical investigation has proven to be as valuable as the traditional orientation towards time. Investigating the past via an orientation to place has uncovered the different ways in which people imbue specific places with meaning and how this meaning and process of meaning-making changes over time. This process of imbuing place with meaning can occur in a number of ways. It can occur experientially, that is, by living in it and interacting with it physically on an individual level. It can also be made socially and culturally, via collective interactions and experiences of place that are shared amongst a group. Place can also be given meaning through cognitive means – place can be imagined and connected with sometimes from afar. Memory is one such means through which this can occur. Memory plays a significant role in associating meaning with place, as remembering a past is crucial for a sense of identity. This past is bound not only in time, but in place. The themes of place, experience, meaning, and memory bring us to modern-day South Africa, where its post-apartheid environment has brought about new values, goals, and visions of society and nation. In breaking with its apartheid past, creating a unified national identity, and promoting a new image of democracy to itself and to the world, South Africa has looked to present a 'collective representation of the past' in order to create a new imagined community in moving forward. -

Cape Town Rd R L N W Or T

Legend yS Radisson SAS 4 C.P.U.T. u# D S (Granger Bay Campus) H R u Non-Perennial River r Freeway / National Road R C P A r E !z E l e T Mouille Point o B . Granger Bay ast y A t Perennial River h B P l Village E Yacht Club e Through Route &v e A d ie x u# s Granger r a Ü C R P M R a H nt n d H . r l . R y hN a e d y d u# Ba G Bay L i % Railway with Station r R ra r P E P The Table Minor Road a D n te st a Table Bay Harbour l g a a 7 La Splendina . e s N R r B w Bay E y t ay MetropolitanO a ak a P Water 24 R110 Route Markers K han W y re u i n1 à î d ie J Step Rd B r: u# e R w Q r ie Kings Victoria J Park / Sports Ground y t W 8} e a L GREEN POINT Wharf 6 tt B a. Fort Wynyard Warehouse y y Victoria Built-up Area H St BMW a E K J Green Point STADIUM r 2 Retail Area Uà ge Theatre Pavillion r: 5 u lb Rd an y Q Basin o K Common Gr @ The |5 J w Industrial Area Pavillion!C Waterfront ua e Service Station B Greenpoint tt çc i F Green Point ~; Q y V & A WATERFRONT Three Anchor Bay ll F r: d P ri o /z 1 R /z Hospital / Clinic with Casualty e t r CHC Red Shed ÑG t z t MARINA m u# Hotel e H d S Cape W Somerset Quay 4 r r y Craft A s R o n 1x D i 8} n y th z Hospital / Clinic le n Medical a Hospital Warehouse u 0 r r ty m Green Point Club .