Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bc Community Forest Perspectives and Engagement in Wildfire Management

BC COMMUNITY FOREST PERSPECTIVES AND ENGAGEMENT IN WILDFIRE MANAGEMENT September 2020 BC COMMUNITY FOREST PERSPECTIVES AND ENGAGEMENT IN WILDFIRE MANAGEMENT. SEPTEMBER 2020 This study was conducted by researchers in the Faculty of Forestry at the University of British Columbia. Funding was provided by a Community Solutions Grant from the Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies at the University of British Columbia. Research Team Dr. Lori D. Daniels Forest and Conservation Sciences, Faculty of Forestry, UBC [email protected] Dr. Shannon M. Hagerman Forest Resources Management, Faculty of Forestry, UBC [email protected] Kelsey Copes-Gerbitz Forest and Conservation Sciences, Faculty of Forestry, UBC [email protected] Sarah Dickson-Hoyle Forest and Conservation Sciences, Faculty of Forestry, UBC [email protected] Acknowledgements We thank the interview participants for providing their views and insights. Project partners for this work comprise: the Union of BC Municipalities (UBCM), First Nations’ Emergency Services Society (FNESS), BC Community Forest Association (BCCFA) and BC Wildfire Service (BCWS). The UBCM, FNESS and BCWS are members of British Columbia’s Provincial Fuel Management Working Group, which managed the Strategic Wildfire Prevention Initiative (SWPI), recently replaced by the Community Resiliency Investment Program (CRIP). Cover image: Post-harvest burn, Harrop-Procter Community Forest. Photo credit: Erik Leslie. Citation Copes-Gerbitz, K., S. Dickson-Hoyle, S.M. Hagerman, and L.D. Daniels. 2020. BC Community Forest Perspectives and Engagement in Wildfire Management. Report to the Union of BC Municipalities, First Nations’ Emergency Services Society, BC Community Forest Association and BC Wildfire Service. September 2020. 49 pp. -

STEWARDSHIP SUCCESS STORIES and CHALLENGES the Sticky Geranium (Geranium Viscosissimum Var

“The voice for grasslands in British Columbia” MAGAZINE OF THE GRASSLANDS CONSERVATION COUNCIL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Fall 2007 STEWARDSHIP SUCCESS STORIES AND CHALLENGES The Sticky Geranium (Geranium viscosissimum var. viscosissimum) is an attractive hardy perennial wildflower that can be found in the grasslands of the interior. The plant gets its name from the sticky glandular hairs that grow on its stems and leaves. PHOTO BRUNO DELESALLE 2 BCGRASSLANDS MAGAZINE OF THE GRASSLANDS CONSERVATION COUNCIL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Fall 2007 The Grasslands Conservation Council of British Columbia (GCC) was established as a society in August 1999 and as a registered charity on December 21, IN THIS ISSUE 2001. Since our beginning, we have been dedicated to promoting education, FEATURES conservation and stewardship of British Columbia’s grasslands in collaboration with 13 The Beauty of Pine Butte Trish Barnes our partners, a diverse group of organizations and individuals that includes Ashcroft Ranch Amber Cowie government, range management specialists, 16 ranchers, agrologists, ecologists, First Nations, land trusts, conservation groups, recreationists and grassland enthusiasts. The GCC’s mission is to: • foster greater understanding and appreciation for the ecological, social, economic and cultural impor tance of grasslands throughout BC; • promote stewardship and sustainable management practices that will ensure the long-term health of BC’s grasslands; and • promote the conservation of representative grassland ecosystems, species at risk and GCC IN -

Oil and Gas Resource Potential of the Bowser-Whitehorse Area of British Columbia

OIL AND GAS RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF THE BOWSER-WHITEHORSE AREA OF BRITISH COLUMBIA by Peter Hannigan, P. J. Lee, and K. G. Osadetz Petroleum Resources Subdivision Geological Survey of Canada - Calgary 3303 - 33 Street N. W. Calgary, Alberta T2L 2A7 March, 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................. 3 GEOLOGICAL SETTING AND PLAY PARAMETERS .......................................................... 6 Bowser Skeena Structural Gas Play........................................................................................ 6 Bowser Skeena Structural Oil Play......................................................................................... 8 Bowser Mid-Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous Structural Gas Play ............................................... 8 Sustut Upper Cretaceous Structural Gas Play ........................................................................10 Sustut Upper Cretaceous Structural Oil Play......................................................................... 11 Northern Rocky Mountain Trench Sifton Structural Gas Play ............................................. 12 Whitehorse Cenozoic Stratigraphic Gas Play........................................................................ 12 Whitehorse Takwahoni Structural Gas Play......................................................................... -

Zone 12 - Northern Interior and Prince George

AFFORDABLE HOUSING Choices for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities Zone 12 - Northern Interior and Prince George The Housing Listings is a resource directory of affordable housing in British Columbia and divides British Columbia into 12 zones. Zone 12 identifies affordable housing in the Northern Interior and Prince George. The attached listings are divided into two sections. Section #1: Apply to The Housing Registry Section 1 - Lists developments that The Housing Registry accepts applications for. These developments are either managed by BC Housing, Non-Profit societies, or Co- Operatives. To apply for these developments, please complete an application form which is available from any BC Housing office, or download the form from www.bchousing.org/housing- assistance/rental-housing/subsidized-housing. Section #2: Apply directly to Non-Profit Societies and Housing Co-ops Section 2 - Lists developments managed by non-profit societies or co-operatives which maintain and fill vacancies from their own applicant lists. To apply for these developments, please contact the society or co-op using the information provided under "To Apply". Please note, some non-profits and co-ops close their applicant list if they reach a maximum number of applicants. In order to increase your chances of obtaining housing it is recommended that you apply for several locations at once. Housing for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities, Zone 12 - Northern Interior and Prince George August 2020 AFFORDABLE HOUSING SectionSection 1:1: ApplyApply toto TheThe HousingHousing RegistryRegistry forfor developmentsdevelopments inin thisthis section.section. Apply by calling 250-562-9251 or, from outside Prince George, 1-800-667-1235. -

Points of Service

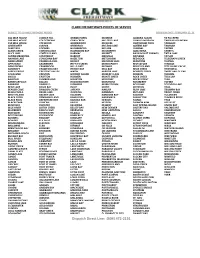

CLARK FREIGHTWAYS POINTS OF SERVICE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE REVISION DATE: FEBRUARY 12, 21 100 MILE HOUSE COBBLE HILL GRAND FORKS MCBRIDE QUADRA ISLAND TA TA CREEK 108 MILE HOUSE COLDSTREAM GRAY CREEK MCLEESE LAKE QUALICUM BEACH TABOUR MOUNTAIN 150 MILE HOUSE COLWOOD GREENWOOD MCGUIRE QUATHIASKI COVE TADANAC AINSWORTH COMOX GRINDROD MCLEOD LAKE QUEENS BAY TAGHUM ALERT BAY COOMBS HAGENSBORG MCLURE QUESNEL TAPPEN ALEXIS CREEK CORDOVA BAY HALFMOON BAY MCMURPHY QUILCHENA TARRY'S ALICE LAKE CORTES ISLAND HARMAC MERRITT RADIUM HOT SPRINGS TATLA LAKE ALPINE MEADOWS COURTENAY HARROP MERVILLE RAYLEIGH TAYLOR ANAHIM LAKE COWICHAN BAY HAZELTON METCHOSIN RED ROCK TELEGRAPH CREEK ANGELMONT CRAIGELLA CHIE HEDLEY MEZIADIN LAKE REDSTONE TELKWA APPLEDALE CRANBERRY HEFFLEY CREEK MIDDLEPOINT REVELSTOKE TERRACE ARMSTRONG CRANBROOK HELLS GATE MIDWAY RIDLEY ISLAND TETE JAUNE CACHE ASHCROFT CRAWFORD BAY HERIOT BAY MILL BAY RISKE CREEK THORNHILL ASPEN GROVE CRESCENT VALLEY HIXON MIRROR LAKE ROBERTS CREEK THREE VALLEY GAP ATHALMER CRESTON HORNBY ISLAND MOBERLY LAKE ROBSON THRUMS AVOLA CROFTON HOSMER MONTE CREEK ROCK CREEK TILLICUM BALFOUR CUMBERLAND HOUSTON MONTNEY ROCKY POINT TLELL BARNHARTVALE DALLAS HUDSONS HOPE MONTROSE ROSEBERRY TOFINO BARRIERE DARFIELD IVERMERE MORICETOWN ROSSLAND TOTOGGA LAKE BEAR LAKE DAVIS BAY ISKUT MOYIE ROYSTON TRAIL BEAVER COVE DAWSON CREEK JAFFARY NAKUSP RUBY LAKE TRIUMPH BAY BELLA COOLA DEASE LAKE JUSKATLA NANAIMO RUTLAND TROUT CREEK BIRCH ISLAND DECKER LAKE KALEDEN NANOOSE BAY SAANICH TULAMEEN BLACK CREEK DENMAN ISLAND -

Burns Lake and Surrounding Area Profile

BURNS LAKE AND SURROUNDING AREA PROFILE SMITHERS | TELKWA | HOUSTON | GRANISLE | BURNS LAKE FRASER LAKE | FORT ST. JAMES | VANDERHOOF CONTENTS 1. 2. 4. COMMUNITY PROFILE ELECTORAL AREA B REGIONAL DISTRICT DEMOGRAPHIC DATA DEMOGRAPHIC DATA OF BULKLEY-NECHAKO Population Growth Population Growth PROFILE Age Structure Age Structure Household Income Household Income DEMOGRAPHIC DATA Population Growth WORKFORCE PROFILE WORKFORCE PROFILE Age Structure Employment Employment Ethnic Diversity Education Education Household Income Labour Force by Industry Labour Force by Industry Local Post-Secondary Education Facilities and WORKFORCE PROFILE Employment Service Providers LOCAL GOVERNMENT Employment Links to Official Plan and Zoning Documents Education TRANSPORTATION Local Economic Development Services Labour Force by Industry Electoral Area Director Contact Post-Secondary Education Facilities COMMUNICATIONS SERVICE PROVIDERS QUALITY OF LIFE FACTORS CLIMATE WATER AND WASTE Local Community Organizations Monthly Temperature Water Local Community Assets Wind Speed Solid Waste Disposal Services Schools Precipitation LOCAL GOVERNMENT FIRST NATIONS COMMUNITY TRANSPORTATION Taxes Burns Lake Band Road Development Processes and Fees Lake Babine Nation Rail Links to Official Plan and Zoning Documents Wet’suwet’en First Nation Airport Incentive Programs Local Economic Development Services 3. ENERGY AND UTILITIES Mayor Contact Electricity and Gas Service Providers Commercial and Residential Rates for Electricity QUALITY OF LIFE FACTORS ELECTORAL AREA E and Gas -

C02-Side View

FULTON RESERVOIR REGULATING BUILDING ACCESS STAIR REPLACEMENT REFERENCE ONLY FOR DRAWING LIST JULY 30, 2019 Atlin ● Atlin Atlin C00 COVER L Liard R C01 SITE PLAN C02 SIDE VIEW Dease Lake ● Fort ine R ● S1.1 GENERAL NOTES AND KEY PLAN kkiii Nelson tititi SS S3.1 DETAILS SHEET 1 S3.2 DETAILS SHEET 2 S3.3 DETAILS SHEET 2 Stewart Fort St ●Stewart Hudson’s John Williston Hope John L ● New Dawson● Creek Dixon upert Hazelton ● ● ● Entrance cce R Mackenzie Chetwynd iiinn Smithers ● Terrace Smithers Masset PrPr ● ● ● ● ● Tumbler Ridge Queen ttt Kitimat Houston Fort Ridge iii Kitimat ●Houston ● ● Charlotte sspp Burns Lake ● St James dds Burns Lake San Fraser R ●● a Fraser Lake ● ● Fraser R Haida Gwaii HecateHecate StrStr Vanderhoof ● Prince George McBride Quesnel ● Quesnel ● ● Wells Bella Bella ● Valemount● Bella Bella ● Bella Williams Valemount Queen Coola Lake Kinbasket Charlotte ● Kinbasket L Sound FraserFraserFraser R RR PACIFIC OCEAN ColumbiaColumbia ●100 Mile Port House Hardy ● ● Port McNeill Revelstoke Golden ●● Lillooet Ashcroft ● Port Alice Campbell Lillooet RR Campbell ● ● ● ● River Kamloops Salmon Arm ● Vancouver Island Powell InvermereInvermere ●StrStr Whistler Merritt ●Vernon Nakusp Courtenay ●River ● ● ●Nakusp ● Squamish Okanagan Kelowna Elkford● Port ofofSechelt ● ●Kelowna Alberni G ● L Kimberley Alberni eeoror Vancouver Hope Penticton Nelson ● Tofino ● ● giagia ● ● ● ● ee ● ● ● Castlegar Cranbrook Ucluelet ● oo ● ksvillvillm o● ●Abbotsford Osoyoos Creston Parks aim ● ●Trail ●Creston Nan mithithith ●Sidney Ladys ●Saanich JuanJuan -

IDP-List-2012.Pdf

INFANT DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Revised January 2012 Website: www.idpofbc.ca 1 Contact information for each Program including addresses and telephone numbers is listed on the pages noted below. This information is also available on our website: www.idpofbc.ca *Aboriginal Infant Development Program Pages 2-3 VANCOUVER COASTAL REGION Vancouver Sheway Richmond *So-Sah-Latch Health & Family Centre, N Vancouver North Shore Sea to Sky, Squamish Burnaby Sunshine Coast, Sechelt New Westminster Powell River Coquitlam *Bella Coola Ridge Meadows, Maple Ridge Pages 4-5 FRASER REGION Delta *Kla-how-eya, Surrey Surrey/White Rock Upper Fraser Valley Langley Pages 6-8 VANCOUVER ISLAND REGION Victoria * Laichwiltach Family Life Society *South Vancouver Island AIDP *Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Gold River Cowichan Valley, Duncan *‘Namgis First Nation, Alert Bay *Tsewultun Health Centre, Duncan *Quatsino Indian Band, Coal Harbour Nanaimo North Island, Port Hardy Port Alberni *Gwa’Sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Family Services, Pt. Hardy *Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Port Alberni* Klemtu Health Clinic, Port Hardy *Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Tofino *Kwakiutl Indian Band, Port Hardy Oceanside, Qualicum Beach Comox Valley, Courtenay Campbell River Pages 9-12 INTERIOR REGION Princeton *First Nations Friendship Centre Nicola Valley, Merritt Kelowna *Nzen’man’ Child & Family, Lytton *KiLowNa Friendship Society, Kelowna Lillooet South Okanagan, Penticton; Oliver Kamloops *Lower Similkameen Indian Band, Keremeos Clearwater Boundary, Grand Forks South Cariboo, 100 Mile House West Kootenay, Castlegar Williams Lake Creston *Bella Coola East Kootenay, Cranbrook; Invermere Salmon Arm Golden *Splatstin, Enderby Revelstoke Vernon Pages 13-14 NORTH REGION Quesnel Golden Kitimat Robson*Splatsin, Valley Enderby Prince RupertRevelstoke Prince George Queen Charlotte Islands Vanderhoof Mackenzie *Tl’azt’en Nation, Tachie South Peace, Dawson Creek Burns Lake Fort St. -

Regional Skills Gap Analysis Regional District of Bulkley-Nechako

Regional Skills Gap Analysis Regional District of Bulkley-Nechako January, 2014 1 Millier Dickinson Blais: Bulkley-Nechako Regional Skills Gaps Analysis ---- RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents 1 REPORT APPROACH ........................................................................................................ 10 2 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS ................................................................................................. 11 2.1 GLOBAL TRENDS 11 2.2 NATIONAL TRENDS 13 2.3 PROVINCIAL TRENDS 14 2.4 REGIONAL TRENDS 19 3 LABOUR SUPPLY AND DEMAND .................................................................................... 27 3.1 RECENT TRENDS 27 3.2 DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL FOR THE BULKLEY-NECHAKO AREA 27 3.3 OCCUPATIONAL REQUIREMENTS TO 2021 34 4 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND CAPACITY ................................................................ 46 4.1 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROCESS 46 4.2 LOCAL TRAINING AND EDUCATION CAPACITY 47 4.3 MAJOR CONSULTATION THEMES 48 5 A STRATEGIC APPROACH TO THE REGIONAL SKILLS GAP ....................................... 52 5.1 RECOMMENDED GOALS AND STRATEGIC ACTIONS 54 6 SUPPORTING RESEARCH DOCUMENTATION ............................................................... 61 6.1 RESEARCH PAPER 1: KEY STAKEHOLDER INTERVIEW ASSESSMENT 61 6.2 RESEARCH PAPER 2: EMPLOYER SURVEY RESULTS 70 6.3 RESEARCH PAPER 3: RESIDENT SURVEY RESULTS 95 6.4 RESEARCH PAPER 4: FOCUS GROUP RESULTS 108 6.5 RESEARCH PAPER 5: COMMUNITY INFORMATION SUMMIT RESULTS 113 6.6 RESEARCH PAPER 6: FIRST NATIONS COMMUNITIES DISCUSSION -

Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study On

Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study on the Enbridge Gateway Pipeline An Assessment of the Impacts of the Proposed Enbridge Gateway Pipeline on the Carrier Sekani First Nations May 2006 Carrier Sekani Tribal Council i Aboriginal Interests & Use Study on the Proposed Gateway Pipeline ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study was carried out under the direction of, and by many members of the Carrier Sekani First Nations. This work was possible because of the many people who have over the years established the written records of the history, territories, and governance of the Carrier Sekani. Without this foundation, this study would have been difficult if not impossible. This study involved many community members in various capacities including: Community Coordinators/Liaisons Ryan Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Bev Ketlo, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Sara Sam, Nak’azdli First Nation Rosa McIntosh, Saik’uz First Nation Bev Bird & Ron Winser, Tl’azt’en Nation Michael Teegee & Terry Teegee, Takla Lake First Nation Viola Turner, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Elders, Trapline & Keyoh Holders Interviewed Dick A’huille, Nak’azdli First Nation Moise and Mary Antwoine, Saik’uz First Nation George George, Sr. Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Rita George, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Patrick Isaac, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Peter John, Burns Lake Band Alma Larson, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Betsy and Carl Leon, Nak’azdli First Nation Bernadette McQuarry, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Aileen Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Donald Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Guy Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Vince Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Kenny Sam, Burns Lake Band Lillian Sam, Nak’azdli First Nation Ruth Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Ryan Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Joseph Tom, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Translation services provided by Lillian Morris, Wet’suwet’en First Nation. -

North Coast Region Agriculture Profile

North Coast Region Agriculture Profile Key Features: Gwaii, Prince Rupert, Terrace and Kitimat with • Rainfall varies considerably within southern centers. Prince Rupert has the largest deep the North Coast region. seaport, but Kitimat and Stewart also boast • Climate varies considerably. deep-sea facilities. • River valleys comprise most of the � The economy of the region is as farm land. diverse as its topography. The coastal • Ranching dominates agricultural communities rely heavily on fishing production. and fish processing. There is logging • Large commercial fishing industry on Haida Gwaii and in the southern represents 65% of salmon and two-thirds of the mainland portion of the 85% of halibut landings in British region. Pulp and paper mills are located Columbia. at Prince Rupert and Kitimat, and • Fish processing dominates the food major sawmills at Terrace, Kitwanga processing industry. and Hazelton. Mining and forestry are the chief economic Population 56,145 activities in the Stewart area. Number of Farms 126 Prince Rupert and Terrace are Land in ALR 109,207 ha the leading administrative and service centers for Area of Farms 8,439 ha the region. Kitimat was established in the early Total Farm Capital $76.1 million 1950s to house Alcan’s aluminum smelter complex, Jobs 638 weeks paid but its industrial base has since expanded to include labour annually forest products and petrochemical production. Gross Farm Receipts $2.4 million Tourism is providing new opportunities in much of Annual Farm Wages $440,183 the region. The North Coast Region Land The North Coast region borders the Pacific Ocean Most of the best quality agricultural land in the and the Alaska Panhandle and includes the Haida region is found in the Kitimat-Stikine district, where Gwai. -

Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan 1

Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan 1 BURNS LAKE RURAL AND FRANCOIS LAKE (NORTH SHORE) OFFICIAL COMMUNITY PLAN BYLAW No. 1785, 2017 Schedule “A” Regional District of Bulkley-Nechako PLANNING DEPARTMENT RD 37 – 3 AVENUE PHONE (250) 692-3195 P.O. BOX 820 TOLL-FREE (800) 320-3339 BURNS LAKE, BRITISH COLUMBIA FAX (250) 692-1220 V0J 1E0 EMAIL: [email protected] RDBN Bylaw No. 1785, 2016 Section 1: Introduction January 12, 2017 2 Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan Please note that this document (Schedule “A”) is one of three parts of the Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan. This Plan also includes the Land Use Designation Map (Schedule “B”) and the Ecological and Wildlife Values Map (Schedule “C”) to which this document refers. Both maps can be viewed at the Regional District office. If you wish to obtain a copy of either map, large format copying charges apply. The maps are also available on the Regional District’s website: www.rdbn.bc.ca. Section 1: Introduction RDBN Bylaw No. 1785, 2017 LIST OF OCP AMENDMENTS Area B, E Commencing 2018 LIST OF OCP AMENDMENTS # BYLAW NO ADOPTION DATE CONTENT FOLIO NO. 1 1834 June 21, 2018 Designation changed from 755/10391.100 RE to RR 2 1913 September 17, 2020 Designation changed from 755/10382.000 “Resource (RE)” to “Rural Residential (RR)” Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan 3 Table of Contents SECTION 1 – INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 4 1.1 Purpose .................................................................................................