The December 2012 Mayo River Debris Flow Triggered by Super Typhoon Bopha in Mindanao, Philippines: Lessons Learned and Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Disasters in the Philippines: a Case Study of the Immediate Causes and Root Drivers From

Zhzh ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Environment & Natural Resources Program Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/ENRP The authors of this report invites use of this information for educational purposes, requiring only that the reproduced material clearly cite the full source: Franta, Benjamin, et al, “Climate disasters in the Philippines: A case study of immediate causes and root drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, November 2016. Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A destroyed church in Samar, Philippines, in the months following Typhoon Yolanda/ Haiyan. (Benjamin Franta) Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 The Environment and Natural Resources Program (ENRP) The Environment and Natural Resources Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs is at the center of the Harvard Kennedy School’s research and outreach on public policy that affects global environment quality and natural resource management. -

American Meteorological Society 2011 Student Conference Paper

Sea Surface Height and Intensity Change in Western North Pacific Typhoons Julianna K. Kurpis, Marino A. Kokolis, and Grace Terdoslavich: Bard High School Early College, Long Island City, New York Jeremy N. Thomas and Natalia N. Solorzano: Digipen Institute of Technology& Northwest Research Associates, Redmond, Washington Abstract Eastern/Central Pacific Hurricane Felicia (2009) Western North Pacific Typhoon Durian (2006) Although the structure of tropical cyclones (TCs) is well known, there are innumerable factors that contribute to their formation and development. The question that we choose to assess is at the very foundation of what conditions are needed for TC genesis and intensification: How does ocean heat content contribute to TC intensity change? Today, it is generally accepted that warm water promotes TC development. Indeed, TCs can be modeled as heat engines that gain energy from the warm water and, in turn, make the sea surface temperature (SST) cooler. Our study tests the relationship between the heat content of the ocean and the intensification process of strong Western North Pacific (WNP) Typhoons (sustained winds greater than 130 knots). We obtained storm track and wind speed data from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center and sea surface height (SSH) data from AVISO as a merged product from altimeters on three satellites: Jason-1, November/December: 25 26 27 28 29 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 Aug: 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Jason-2, and Envisat. We used MATLAB to compare the SSH to the wind speeds, The strongest wind for Typhoon Durian occurred when the SSH was below using these as proxies for ocean heat content and intensity, respectively. -

A Domestication Strategy of Indigenous Premium Timber Species by Smallholders in Central Visayas and Northern Mindanao, the Philippines

A DOMESTICATION STRATEGY OF INDIGENOUS PREMIUM TIMBER SPECIES BY SMALLHOLDERS IN CENTRAL VISAYAS AND NORTHERN MINDANAO, THE PHILIPPINES Autor: Iria Soto Embodas Supervisors: Hugo de Boer and Manuel Bertomeu Garcia Department: Systematic Botany, Uppsala University Examyear: 2007 Study points: 20 p Table of contents PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. CONTEXT OF THE STUDY AND RATIONALE 3 3. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY 18 4. ORGANIZATION OF THE STUDY 19 5. METHODOLOGY 20 6. RESULTS 28 7. DISCUSSION: CURRENT CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR DOMESTICATING PREMIUM TIMBER SPECIES 75 8. TOWARDS REFORESTATION WITH PREMIUM TIMBER SPECIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: A PROPOSAL FOR A TREE 81 DOMESTICATION STRATEGY 9. REFERENCES 91 1. INTRODUCTION The importance of the preservation of the tropical rainforest is discussed all over the world (e.g. 1972 Stockholm Conference, 1975 Helsinki Conference, 1992 Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, and the 2002 Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development). Tropical rainforest has been recognized as one of the main elements for maintaining climatic conditions, for the prevention of impoverishment of human societies and for the maintenance of biodiversity, since they support an immense richness of life (Withmore, 1990). In addition sustainable management of the environment and elimination of absolute poverty are included as the 21 st Century most important challenges embedded in the Millennium Development Goals. The forest of Southeast Asia constitutes, after the South American, the second most extensive rainforest formation in the world. The archipelago of tropical Southeast Asia is one of the world's great reserves of biodiversity and endemism. This holds true for The Philippines in particular: it is one of the most important “biodiversity hotspots” .1. -

Typhoon Neoguri Disaster Risk Reduction Situation Report1 DRR Sitrep 2014‐001 ‐ Updated July 8, 2014, 10:00 CET

Typhoon Neoguri Disaster Risk Reduction Situation Report1 DRR sitrep 2014‐001 ‐ updated July 8, 2014, 10:00 CET Summary Report Ongoing typhoon situation The storm had lost strength early Tuesday July 8, going from the equivalent of a Category 5 hurricane to a Category 3 on the Saffir‐Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, which means devastating damage is expected to occur, with major damage to well‐built framed homes, snapped or uprooted trees and power outages. It is approaching Okinawa, Japan, and is moving northwest towards South Korea and the Philippines, bringing strong winds, flooding rainfall and inundating storm surge. Typhoon Neoguri is a once‐in‐a‐decade storm and Japanese authorities have extended their highest storm alert to Okinawa's main island. The Global Assessment Report (GAR) 2013 ranked Japan as first among countries in the world for both annual and maximum potential losses due to cyclones. It is calculated that Japan loses on average up to $45.9 Billion due to cyclonic winds every year and that it can lose a probable maximum loss of $547 Billion.2 What are the most devastating cyclones to hit Okinawa in recent memory? There have been 12 damaging cyclones to hit Okinawa since 1945. Sustaining winds of 81.6 knots (151 kph), Typhoon “Winnie” caused damages of $5.8 million in August 1997. Typhoon "Bart", which hit Okinawa in October 1999 caused damages of $5.7 million. It sustained winds of 126 knots (233 kph). The most damaging cyclone to hit Japan was Super Typhoon Nida (reaching a peak intensity of 260 kph), which struck Japan in 2004 killing 287 affecting 329,556 people injuring 1,483, and causing damages amounting to $15 Billion. -

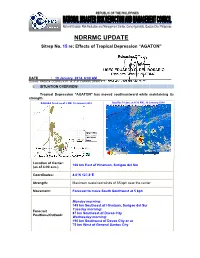

Nd Drrm C Upd Date

NDRRMC UPDATE Sitrep No. 15 re: Effects of Tropical Depression “AGATON” Releasing Officer: USEC EDUARDO D. DEL ROSARIO Executive Director, NDRRMC DATE : 19 January 2014, 6:00 AM Sources: PAGASA, OCDRCs V,VII, IX, X, XI, CARAGA, DPWH, PCG, MIAA, AFP, PRC, DOH and DSWD I. SITUATION OVERVIEW: Tropical Depression "AGATON" has moved southeastward while maintaining its strength. PAGASA Track as of 2 AM, 19 January 2014 Satellite Picture at 4:32 AM., 19 January 2014 Location of Center: 166 km East of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur (as of 4:00 a.m.) Coordinates: 8.0°N 127.8°E Strength: Maximum sustained winds of 55 kph near the center Movement: Forecast to move South Southwest at 5 kph Monday morninng: 145 km Southeast of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur Tuesday morninng: Forecast 87 km Southeast of Davao City Positions/Outlook: Wednesday morning: 190 km Southwest of Davao City or at 75 km West of General Santos City Areas Having Public Storm Warning Signal PSWS # Mindanao Signal No. 1 Surigao del Norte (30-60 kph winds may be expected in at Siargao Is. least 36 hours) Surigao del Sur Dinagat Province Agusan del Norte Agusan del Sur Davao Oriental Compostela Valley Estimated rainfall amount is from 5 - 15 mm per hour (moderate - heavy) within the 300 km diameter of the Tropical Depression Tropical Depression "AGATON" will bring moderate to occasionally heavy rains and thunderstorms over Visayas Sea travel is risky over the seaboards of Luzon and Visayas. The public and the disaster risk reduction and management councils concerned are advised to take appropriate actions II. -

VIETNAM: TYPHOONS 23 January 2007 the Federation’S Mission Is to Improve the Lives of Vulnerable People by Mobilizing the Power of Humanity

Appeal No. MDRVN001 VIETNAM: TYPHOONS 23 January 2007 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in 185 countries. In Brief Operations Update no. 03; Period covered: 10 December - 18 January 2007; Revised Appeal target: CHF 4.2 million (USD 3.4 million or EUR 2.6 million) Appeal coverage: 26%; outstanding needs: CHF 3.1 million (Click here for the attached Contributions List)(click here for the live update) Appeal history: • Preliminary emergency appeal for Typhoon Xangsane launched on 5 Oct 2006 to seek CHF 998,110 (USD 801,177 OR EUR 629,490) for 61,000 beneficiaries for 12 months. • The appeal was revised on 13 October 2006 to CHF 1.67 million (USD 1.4 million or EUR 1.1 million) for 60,400 beneficiaries to reflect operational realities. • The appeal was relaunched as Viet Nam Typhoons Emergency Appeal (MDRVN001) on 7 December 2006 to incorporate Typhoon Durian. It requests CHF 4.2 million (USD 3.4 million or EUR 2.6 million) in cash, kind, or services to assist 98,000 beneficiaries for 12 months. • Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) allocated: for Xangsane and Durian at CHF 100,000 each. Operational Summary: The Viet Nam Red Cross (VNRC), through its headquarters and its chapters, are committed towards supporting communities affected by a series of typhoons (Xangsane and Durian). The needs are extensive, with 20 cities and provinces stretching from the central regions to southern parts of the country hit hard with losses to lives, property and livelihoods. -

Efforts for Emergency Observation Mapping in Manila Observatory

Efforts for Emergency Observation Mapping in Manila Observatory: Development of a Typhoon Impact Estimation System (TIES) focusing on Economic Flood Loss of Urban Poor Communities in Metro Manila UN-SPIDER International Conference on Space-based Technologies for Disaster Risk Reduction – “Enhancing Disaster Preparedness for Effective Emergency Response” Session 4: Demonstrating Advances in Earth Observation to Build Back Better September 25, 2018 Ma. Flordeliza P. Del Castillo Manila Observatory EMERGENCY OBSERVATION MAPPING IN MANILA OBSERVATORY • Typhoon Reports • Sentinel Asia Data Analysis Node (2011-present) • Flood loss estimation for urban poor households in Metro Manila (2016-present) 1. Regional Climate Systems (RCS) – Hazard analysis (Rainfall and typhoon forecast) 2. Instrumentation and Efforts before typhoon arrives Technology Development – Automated Weather Stations 3. Geomatics for Environment and Development – Mapping and integration of Hazard, Exposure and Vulnerability layers Observing from space and also from the ground. Efforts during typhoon event Now, incorporating exposure and vulnerability variables Efforts after a typhoon event Data Analysis Node (Post- Disaster Event) Image Source: Secretariat of Sentinel Asia Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, Sentinel Asia Annual Report 2016 MO Emergency Observation (EO) and Mapping Protocol (15 October 2018) Step 1: Step 2: Step 3: Establish the Apply for EMERGENCY Elevate status to LOCATION/COVERAGE of OBSERVATION to International Disaster EOR Sentinel Asia (SA) Charter (IDC) by ADRC Step 6: Step 5: Step 4: Upload maps in MO, SA MAP Download images & IDC websites PRODUCTION Emergency Observation Mapping Work • December 2011 – T.S. Washi “Sendong” • August 2012 – Southwest Monsoon Flood “Habagat” • ” Emergency Observation Mapping Work • December 2011 – T.S. Washi “Sendong” • August 2012 – Southwest Monsoon Flood “Habagat” • December 2012 – Bopha “Pablo” • August 2013 – Southwest Monsoon Flood and T.S. -

Top 15 Lgus with Highest Poverty Incidence, Davao Region, 2012)

Table 1. City and Municipal-Level Small Area Poverty Estimates (Top 15 LGUs with Highest Poverty Incidence, Davao Region, 2012) Rank Province Municipality Poverty Incidence (%) 1 Davao Occidental Jose Abad Santos (Trinidad) 75.5 2 Davao Occidental Don Marcelino 73.8 3 Davao del Norte Talaingod 68.8 4 Davao Occidental Saragani 65.9 5 Davao Occidental Malita 60.8 6 Davao Oriental Manay 58.1 7 Davao Oriental Tarragona 56.9 8 Compostela Valley Laak (San Vicente) 53.8 9 Davao del Sur Kiblawan 52.9 10 Davao Oriental Caraga 51.6 11 Davao Occidental Santa Maria 50.7 12 Davao del Norte San Isidro 43.2 13 Davao del Norte New Corella 41.6 14 Compostela Valley Montevista 40.2 15 Davao del Norte Asuncion (Saug) 39.2 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority Note: The 2015 Small Area Poverty Estimates is not yet available. Table 2. Geographically-Isolated and Disadvantaged Areas (GIDAs) PROVINCE/HUC CITY/MUNICIPALITY BARANGAYS Baganga Binondo, Campawan, Mahan-ob Boston Caatihan, Simulao Caraga Pichon, Sobreacrey, San Pedro Cateel Malibago Davao Oriental Gov. Generoso Ngan Lupon Don Mariano, Maragatas, Calapagan Manay Taokanga, Old Macopa Mati City Langka, Luban, Cabuaya Tarragona Tubaon, Limot Asuncion Camansa, Binancian, Buan, Sonlon IGaCoS Pangubatan, Bandera, San Remegio, Libertad, San Isidro, Aundanao, Tagpopongan, Kanaan, Linosutan, Dadatan, Sta. Cruz, Cogon Davao del Norte Kapalong Florida, Sua-on, Gupitan San Isidro Monte Dujali, Datu Balong, Dacudao, Pinamuno Sto. Tomas Magwawa Talaingod Palma Gil, Sto. Niño, Dagohoy Laak Datu Ampunan, Datu Davao Mabini Anitapan, Golden Valley Maco Calabcab, Elizalde, Gubatan, Kinuban, Limbo, Mainit, Malamodao, Masara, New Barili, New Leyte, Panangan, Panibasan, Panoraon, Tagbaros, Teresa Maragusan Bahi, Langgawisan Compostela Valley Monkayo Awao, Casoon, Upper Ulip. -

6 2. Annual Summaries of the Climate System in 2009 2.1 Climate In

2. Annual summaries of the climate system in above normal in Okinawa/Amami because hot and 2009 sunny weather was dominant under the subtropical high in July and August. 2.1 Climate in Japan (d) Autumn (September – November 2009, Fig. 2.1.1 Average surface temperature, precipitation 2.1.4d) amounts and sunshine durations Seasonal mean temperatures were near normal in The annual anomaly of the average surface northern and Eastern Japan, although temperatures temperature over Japan (averaged over 17 observatories swung widely. In Okinawa/Amami, seasonal mean confirmed as being relatively unaffected by temperatures were significantly above normal due to urbanization) in 2009 was 0.56°C above normal (based the hot weather in the first half of autumn. Monthly on the 1971 – 2000 average), and was the seventh precipitation amounts were significantly below normal highest since 1898. On a longer time scale, average nationwide in September due to dominant anticyclones. surface temperatures have been rising at a rate of about In contrast, in November, they were significantly 1.13°C per century since 1898 (Fig. 2.1.1). above normal in Western Japan under the influence of the frequent passage of cyclones and fronts around 2.1.2 Seasonal features Japan. In October, Typhoon Melor (0918) made (a) Winter (December 2008 – February 2009, Fig. landfall on mainland Japan, bringing heavy rainfall and 2.1.4a) strong winds. Since the winter monsoon was much weaker than (e) December 2009 usual, seasonal mean temperatures were above normal In the first half of December, temperatures were nationwide. In particular, they were significantly high above normal nationwide, and heavy precipitation was in Northern Japan, Eastern Japan and Okinawa/Amami. -

Typhoon Haiyan Action Plan November 2013

Philippines: Typhoon Haiyan Action Plan November 2013 Prepared by the Humanitarian Country Team 100% 92 million total population of the Philippines (as of 2010) 54% 50 million total population of the nine regions hit by Typhoon Haiyan 13% 11.3 million people affected in these nine regions OVERVIEW (as of 12 November) (12 November 2013 OCHA) SITUATION On the morning of 8 November, category 5 Typhoon Haiyan (locally known as Yolanda ) made a direct hit on the Philippines, a densely populated country of 92 million people, devastating areas in 36 provinces. Haiyan is possibly the most powerful storm ever recorded . The typhoon first ma de landfall at 673,000 Guiuan, Eastern Samar province, with wind speeds of 235 km/h and gusts of 275 km/h. Rain fell at rates of up to 30 mm per hour and massive storm displaced people surges up to six metres high hit Leyte and Samar islands. Many cities and (as of 12 November) towns experienced widespread destruction , with as much as 90 per cent of housing destroyed in some areas . Roads are blocked, and airports and seaports impaired; heavy ships have been thrown inland. Water supply and power are cut; much of the food stocks and other goods are d estroyed; many health facilities not functioning and medical supplies quickly being exhausted. Affected area: Regions VIII (Eastern Visayas), VI (Western Visayas) and Total funding requirements VII (Central Visayas) are hardest hit, according to current information. Regions IV-A (CALABARZON), IV-B ( MIMAROPA ), V (Bicol), X $301 million (Northern Mindanao), XI (Davao) and XIII (Caraga) were also affected. -

WMO Statement on the Status of the Global Climate in 2011

WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2011 WMO-No. 1085 WMO-No. 1085 © World Meteorological Organization, 2012 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chair, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. Box 2300 Fax: +41 (0) 22 730 80 40 CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-92-63-11085-5 WMO in collaboration with Members issues since 1993 annual statements on the status of the global climate. This publication was issued in collaboration with the Hadley Centre of the UK Meteorological Office, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; the Climatic Research Unit (CRU), University of East Anglia, United Kingdom; the Climate Prediction Center (CPC), the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS), the National Hurricane Center (NHC) and the National Weather Service (NWS) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), United States of America; the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) operated by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), United States; the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), United States; the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), United Kingdom; the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC), Germany; and the Dartmouth Flood Observatory, United States. -

Global Catastrophe Review – 2015

GC BRIEFING An Update from GC Analytics© March 2016 GLOBAL CATASTROPHE REVIEW – 2015 The year 2015 was a quiet one in terms of global significant insured losses, which totaled around USD 30.5 billion. Insured losses were below the 10-year and 5-year moving averages of around USD 49.7 billion and USD 62.6 billion, respectively (see Figures 1 and 2). Last year marked the lowest total insured catastrophe losses since 2009 and well below the USD 126 billion seen in 2011. 1 The most impactful event of 2015 was the Port of Tianjin, China explosions in August, rendering estimated insured losses between USD 1.6 and USD 3.3 billion, according to the Guy Carpenter report following the event, with a December estimate from Swiss Re of at least USD 2 billion. The series of winter storms and record cold of the eastern United States resulted in an estimated USD 2.1 billion of insured losses, whereas in Europe, storms Desmond, Eva and Frank in December 2015 are expected to render losses exceeding USD 1.6 billion. Other impactful events were the damaging wildfires in the western United States, severe flood events in the Southern Plains and Carolinas and Typhoon Goni affecting Japan, the Philippines and the Korea Peninsula, all with estimated insured losses exceeding USD 1 billion. The year 2015 marked one of the strongest El Niño periods on record, characterized by warm waters in the east Pacific tropics. This was associated with record-setting tropical cyclone activity in the North Pacific basin, but relative quiet in the North Atlantic.