Course RPD1013 - Understanding Addiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methylphenidate Hydrochloride

Application for Inclusion to the 22nd Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines: METHYLPHENIDATE HYDROCHLORIDE December 7, 2018 Submitted by: Patricia Moscibrodzki, M.P.H., and Craig L. Katz, M.D. The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Graduate Program in Public Health New York NY, United States Contact: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 3 Summary Statement Page 4 Focal Point Person in WHO Page 5 Name of Organizations Consulted Page 6 International Nonproprietary Name Page 7 Formulations Proposed for Inclusion Page 8 International Availability Page 10 Listing Requested Page 11 Public Health Relevance Page 13 Treatment Details Page 19 Comparative Effectiveness Page 29 Comparative Safety Page 41 Comparative Cost and Cost-Effectiveness Page 45 Regulatory Status Page 48 Pharmacoepial Standards Page 49 Text for the WHO Model Formulary Page 52 References Page 61 Appendix – Letters of Support 2 1. Summary Statement of the Proposal for Inclusion of Methylphenidate Methylphenidate (MPH), a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant, of the phenethylamine class, is proposed for inclusion in the WHO Model List of Essential Medications (EML) & the Model List of Essential Medications for Children (EMLc) for treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) under ICD-11, 6C9Z mental, behavioral or neurodevelopmental disorder, disruptive behavior or dissocial disorders. To date, the list of essential medications does not include stimulants, which play a critical role in the treatment of psychotic disorders. Methylphenidate is proposed for inclusion on the complimentary list for both children and adults. This application provides a systematic review of the use, efficacy, safety, availability, and cost-effectiveness of methylphenidate compared with other stimulant (first-line) and non-stimulant (second-line) medications. -

Substance Abuse and Dependence

9 Substance Abuse and Dependence CHAPTER CHAPTER OUTLINE CLASSIFICATION OF SUBSTANCE-RELATED THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES 310–316 Residential Approaches DISORDERS 291–296 Biological Perspectives Psychodynamic Approaches Substance Abuse and Dependence Learning Perspectives Behavioral Approaches Addiction and Other Forms of Compulsive Cognitive Perspectives Relapse-Prevention Training Behavior Psychodynamic Perspectives SUMMING UP 325–326 Racial and Ethnic Differences in Substance Sociocultural Perspectives Use Disorders TREATMENT OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Pathways to Drug Dependence AND DEPENDENCE 316–325 DRUGS OF ABUSE 296–310 Biological Approaches Depressants Culturally Sensitive Treatment Stimulants of Alcoholism Hallucinogens Nonprofessional Support Groups TRUTH or FICTION T❑ F❑ Heroin accounts for more deaths “Nothing and Nobody Comes Before than any other drug. (p. 291) T❑ F❑ You cannot be psychologically My Coke” dependent on a drug without also being She had just caught me with cocaine again after I had managed to convince her that physically dependent on it. (p. 295) I hadn’t used in over a month. Of course I had been tooting (snorting) almost every T❑ F❑ More teenagers and young adults die day, but I had managed to cover my tracks a little better than usual. So she said to from alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents me that I was going to have to make a choice—either cocaine or her. Before she than from any other cause. (p. 297) finished the sentence, I knew what was coming, so I told her to think carefully about what she was going to say. It was clear to me that there wasn’t a choice. I love my T❑ F❑ It is safe to let someone who has wife, but I’m not going to choose anything over cocaine. -

Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: a Research-Based Guide (Third Edition)

Publications Revised January 2018 Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition) Table of Contents Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition) Preface Principles of Effective Treatment Frequently Asked Questions Drug Addiction Treatment in the United States Evidence-Based Approaches to Drug Addiction Treatment Acknowledgments Resources Page 1 Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition) The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. Trade, proprietary, or company names appearing in this publication are used only because they are considered essential in the context of the studies described. Preface Drug addiction is a complex illness. It is characterized by intense and, at times, uncontrollable drug craving, along with compulsive drug seeking and use that persist even in the face of devastating consequences. This update of the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment is intended to address addiction to a wide variety of drugs, including nicotine, alcohol, and illicit and prescription drugs. It is designed to serve as a resource for healthcare providers, family members, and other stakeholders trying to address the myriad problems faced by patients in need of treatment for drug abuse or addiction. Addiction affects multiple brain circuits, including those involved in reward and motivation, learning and memory, and inhibitory control over behavior. That is why addiction is a brain disease. Some individuals are more vulnerable than others to becoming addicted, depending on the interplay between genetic makeup, age of exposure to drugs, and other environmental influences. -

XANAX® Alprazolam Tablets, USP

XANAX® alprazolam tablets, USP CIV WARNING: RISKS FROM CONCOMITANT USE WITH OPIOIDS Concomitant use of benzodiazepines and opioids may result in profound sedation, respiratory depression, coma, and death [see Warnings, Drug Interactions]. Reserve concomitant prescribing of these drugs for use in patients for whom alternative treatment options are inadequate. Limit dosages and durations to the minimum required. Follow patients for signs and symptoms of respiratory depression and sedation. DESCRIPTION XANAX Tablets contain alprazolam which is a triazolo analog of the 1,4 benzodiazepine class of central nervous system-active compounds. The chemical name of alprazolam is 8-Chloro-1-methyl-6-phenyl-4H-s-triazolo [4,3-α] [1,4] benzodiazepine. The structural formula is represented to the right: Alprazolam is a white crystalline powder, which is soluble in methanol or ethanol but which has no appreciable solubility in water at physiological pH. Each XANAX Tablet, for oral administration, contains 0.25, 0.5, 1 or 2 mg of alprazolam. XANAX Tablets, 2 mg, are multi-scored and may be divided as shown below: 1 Reference ID: 4029640 Inactive ingredients: Cellulose, corn starch, docusate sodium, lactose, magnesium stearate, silicon dioxide and sodium benzoate. In addition, the 0.5 mg tablet contains FD&C Yellow No. 6 and the 1 mg tablet contains FD&C Blue No. 2. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Pharmacodynamics CNS agents of the 1,4 benzodiazepine class presumably exert their effects by binding at stereo specific receptors at several sites within the central nervous system. Their exact mechanism of action is unknown. Clinically, all benzodiazepines cause a dose-related central nervous system depressant activity varying from mild impairment of task performance to hypnosis. -

Behavioral Tolerance: Research and Treatment Implications

US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH EDUCATION AND WELFARE • Public Health Service • Alcohol Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration Behavioral Tolerance: Research and Treatment Implications Editor: Norman A. Krasnegor, Ph.D. NIDA Research Monograph 18 January 1978 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration National lnstitute on Drug Abuse Division of Research 5600 Fishers Lane RockviIle. Maryland 20657 For sale by tho Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 (Paper Cover) Stock No. 017-024-00699-8 The NIDA Research Monogroph series iS prepared by the Division of Research of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Its primary objective is to provide critical re- views of research problem areas and techniques. the content of state-of-the-art conferences, integrative research reviews and significant original research its dual publication emphasis iS rapid and targeted dissemination to the scientific and professional community Editorial Advisory Board Avram Goldstein, M.D Addiction Research Foundation Polo Alto California Jerome Jaffe, M.D College Of Physicians and Surgeons Columbia University New York Reese T Jones, M.D Langley Porter Neuropsychitnc Institute University of California San Francisco California William McGlothlin, Ph D Department of Psychology UCLA Los Angeles California Jack Mendelson. M D Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research Center Harvard Medical School McLeon Hospital Belmont Massachusetts Helen Nowlis. Ph.D Office of Drug Education DHEW Washington DC Lee Robins, Ph.D Washington University School of Medicine St Louis Missouri NIDA Research Monograph series Robert DuPont, M.D. DIRECTOR, NIDA William Pollin, M.D. DIRECTOR, DIVISION OF RESEARCH, NIDA Robert C. -

Pharmacology - Neuroadaptation

Pharmacology - Neuroadaptation All drugs of dependence are associated with increased dopamine activity in the so-called reward pathway of the brain-- this pathway that gives us pleasure and tells us what's good for our survival. The overstimulation of the reward system when we use drugs of abuse, or develop an addiction, sets in motion a reinforcing pattern that teaches us to repeat the behaviour. Over time, as drug use and addiction continues and develops, the brain adapts to the overwhelming surges in dopamine. And it adapts by producing less dopamine, by reducing the number and activity of the dopamine receptors, and by essentially turning down the volume on the dopamine system. Our brain strives for balance. In some respects, we can conceptualise it as constantly adapting and changing to function in a way that we can act and feel normal, a process called homeostasis. And when we talk about homeostasis occurring in the brain, we use the term neuroadaptation. When we consume a drug, we alter the functioning of our brain. We upset the balance, and as a result, our brain tries to adapt. It tries to minimise the effect of the drug and get back to normal. If we use a drug frequently, then the brain will adapt to try and be in balance when the drug is present. But if we then stop taking the drug, our brain is no longer in balance, and it can take a really long time for the brain to re-adapt. In psychopharmacology, we refer to these processes as drug tolerance and physical drug dependence. -

Biological Components of Substance Abuse and Addiction

Biological Components of Substance Abuse and Addiction September 1993 OTA-BP-BBS-117 NTIS order #PB94-134624 GPO stock #052-003-01350-9 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Mice of Technology Assessment, BioZogicaZ Components of Substance Abuse and Addiction, OTA-BP-BBS-1 17 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government printing Offke, September 1993). II 10[ \cllc h> 111( I Is ( l(l\ c1 Illllclll 1’1 Illllllp ( )Illcc $L1pCrlfl[L’llL! L’11[ of [)(). UIIIC’111.. \lJl[ $[t~[~ \\( )1’ \\ J.hlllg({lll. [)( ?( l~()? ‘~ ~?h ISBN 0-16 -042096-2 Foreword ubstance abuse and addiction are complex phenomena that defy simple explanation or description. A tangled interaction of factors contributes to an individual’s experimentation with, use, and perhaps subsequent abuse of drugs. Regardless of the mix of contributing factors, the actions and effectss exerted by drugs of abuse underlie all substance abuse and addiction. In order to understand substance abuse and addiction it is first necessary to understand how drugs work in the brain, why certain drugs have the potential for being abused, and what, if any, biological differences exist among individuals in their susceptibility to abuse drugs. This background paper is the first of two documents being produced by OTA as part of an assessment of Technologies for Understanding the Root Causes of Substance Abuse and Addiction. The assessment was requested by the House Committee on Government Operations, the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, and the Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources. This background paper describes biological contributing factors to substance abuse and addiction. The second document being produced by this study will discuss the complex interactions of biochemical, physiological, psychological, and sociological factors leading to substance abuse and addiction. -

Pharmacogenomics: the Promise of Personalized Medicine for CNS Disorders

Neuropsychopharmacology REVIEWS (2009) 34, 159–172 & 2009 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0893-133X/09 $30.00 REVIEW ............................................................................................................................................................... www.neuropsychopharmacology.org 159 Pharmacogenomics: The Promise of Personalized Medicine for CNS Disorders Jose de Leon*,1,2,3,4 1 2 Mental Health Research Center, Eastern State Hospital, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA; College of Medicine, 3 4 University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA; College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA; Psychiatry and Neurosciences Research Group (CTS-549), Institute of Neurosciences, Medical School, University of Granada, Granada, Spain This review focuses first on the concept of pharmacogenomics and its related concepts (biomarkers and personalized prescription). Next, the first generation of five DNA pharmacogenomic tests used in the clinical practice of psychiatry is briefly reviewed. Then the possible involvement of these pharmacogenomic tests in the exploration of early clinical proof of mechanism is described by using two of the tests and one example from the pharmaceutical industry (iloperidone clinical trials). The initial attempts to use other microarray tests (measuring RNA expression) as peripheral biomarkers for CNS disorders are briefly described. Then the challenge of taking pharmacogenomic tests (compared to drugs) into clinical practice is explained by focusing on regulatory -

Prescription Drug Abuse See Page 10

Preventing and recognizing prescription drug abuse See page 10. from the director: The nonmedical use and abuse of prescription drugs is a serious public health problem in this country. Although most people take prescription medications responsibly, an estimated 52 million people (20 percent of those aged 12 and Prescription older) have used prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons at least once in their lifetimes. Young people are strongly represented in this group. In fact, the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s (NIDA) Drug Abuse Monitoring the Future (MTF) survey found that about 1 in 12 high school seniors reported past-year nonmedical use of the prescription pain reliever Vicodin in 2010, and 1 in 20 reported abusing OxyContin—making these medications among the most commonly abused drugs by adolescents. The abuse of certain prescription drugs— opioids, central nervous system (CNS) depressants, and stimulants—can lead to a variety of adverse health effects, including addiction. Among those who reported past-year nonmedical use of a prescription drug, nearly 14 percent met criteria for abuse of or dependence on it. The reasons for the high prevalence of prescription drug abuse vary by age, gender, and other factors, but likely include greater availability. What is The number of prescriptions for some of these medications has increased prescription dramatically since the early 1990s (see figures, page 2). Moreover, a consumer culture amenable to “taking a pill for drug abuse? what ails you” and the perception of 1 prescription drugs as less harmful than rescription drug abuse is the use of a medication without illicit drugs are other likely contributors a prescription, in a way other than as prescribed, or for to the problem. -

Prescription Medications: Misuse, Abuse, Dependence, and Addiction

Substance Abuse Treatment May 2006 Volume 5 Issue 2 ADVISORYNews for the Treatment Field Prescription Medications: Misuse, Abuse, Dependence, and Addiction How serious are prescription Older adults are particularly vulnerable to misuse and medication use problems? abuse of prescription medications. Persons ages 65 and older make up only 13 percent of the population but Development and increased availability of prescription account for one-third of all medications prescribed,3 drugs have significantly improved treatment of pain, and many of these prescriptions are for psychoactive mental disorders, anxiety, and other conditions. Millions medications with high abuse and addiction liability.4 of Americans use prescription medications safely and Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health responsibly. However, increased availability and vari- indicate that nonmedical use of prescription medications ety of medications with psychoactive effects (see Table was the second most common form of substance abuse 1) have contributed to prescription misuse, abuse, among adults older than 55.5 dependence, and addiction. In 2004,1 the number of Americans reporting abuse2 of prescription medications Use of prescription medications in ways other than was higher than the combined total of those reporting prescribed can have a variety of adverse health conse- abuse of cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, and heroin. quences, including overdose, toxic reactions, and serious More than 14.5 million persons reported having used drug interactions leading to life-threatening conditions, prescription medications nonmedically within the past such as respiratory depression, hypertension or hypoten- year. Of this 14.5 million, more than 2 million were sion, seizures, cardiovascular collapse, and death.6 between ages 12 and 17. -

Pharmacogenomic Testing Panels for Major Depressive Disorder

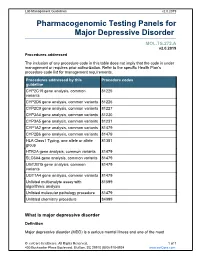

Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2019 Pharmacogenomic Testing Panels for Major Depressive Disorder MOL.TS.272.A v2.0.2019 Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedures addressed by this Procedure codes guideline CYP2C19 gene analysis, common 81225 variants CYP2D6 gene analysis, common variants 81226 CYP2C9 gene analysis, common variants 81227 CYP3A4 gene analysis, common variants 81230 CYP3A5 gene analysis, common variants 81231 CYP1A2 gene analysis, common variants 81479 CYP2B6 gene analysis, common variants 81479 HLA Class I Typing, one allele or allele 81381 group HTR2A gene analysis, common variants 81479 SLC6A4 gene analysis, common variants 81479 UGT2B15 gene analysis, common 81479 variants UGT1A4 gene analysis, common variants 81479 Unlisted multianalyte assay with 81599 algorithmic analysis Unlisted molecular pathology procedure 81479 Unlisted chemistry procedure 84999 What is major depressive disorder Definition Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a serious mental illness and one of the most © eviCore healthcare. All Rights Reserved. 1 of 7 400 Buckwalter Place Boulevard, Bluffton, SC 29910 (800) 918-8924 www.eviCore.com Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2019 common mental disorders in the United States, carrying the heaviest burden of disability among all mental and behavioral disorders. In 2016, roughly 16 million adults in the United States experienced at least one major depression episode in the previous year; this number represented 6.7% of all adults in the United States.1 A major depressive episode can include a number of symptoms, including depressed mood, insomnia or hypersomnia, change in appetite or weight, low energy, poor concentration, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, among other symptoms. -

Advances in and Limitations of Up-And-Down Methodology a Pre´Cis of Clinical Use, Study Design, and Dose Estimation in Anesthesia Research Nathan L

Ⅵ REVIEW ARTICLE David C. Warltier, M.D., Ph.D., Editor Anesthesiology 2007; 107:144–52 Copyright © 2007, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Advances in and Limitations of Up-and-down Methodology A Pre´cis of Clinical Use, Study Design, and Dose Estimation in Anesthesia Research Nathan L. Pace, M.D., M.Stat.,* Mario P. Stylianou, Ph.D.† Sequential design methods for binary response variables of the patient can be observed immediately.1 The earliest exist for determination of the concentration or dose associated use by the anesthesia research community of one partic- with the 50% point along the dose–response curve; the up-and- ular sequential design—the up-and-down method down method of Dixon and Mood is now commonly used in anesthesia research. There have been important developments (UDM)—seems to have been in studies of the effective in statistical methods that (1) allow the design of experiments concentration for a 50% response (EC50 or minimum for the measurement of the response at any point (quantile) alveolar concentration) of inhalation anesthestics.2,3 along the dose–response curve, (2) demonstrate the risk of Columb and Lyons4 used the same design and reported certain statistical methods commonly used in literature reports, the EC —labeled by them the minimum local analgesic (3) allow the estimation of the concentration or dose—the tar- 50 get dose—associated with the chosen quantile without the as- concentration (MLAC)—of epidural bupivacaine and li- sumption of the symmetry of the tolerance distribution, and (4) docaine for pain relief during labor.