The Namesake the Top of Mt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To View & Download My Resume

NAWARA BLUE Producer Driven, organized, detail- WORK EXPERIENCE oriented, and creative professional with extensive Roll Up Your Sleeves (2021 COVID Vaccination Special)- Producer NBC/ Camouflage Films, Inc. (Houston, TX) experience in television production. Skillset includes Put A Ring On It (Season 2)- Supervising Field Producer cultivating stories, tracking OWN / Lighthearted ENT (Atlanta, GA) multiple storylines, producing and directing large cast. Skilled Ready to Love (Season 4)- Supervising Field Producer OWN / Lighthearted ENT (Houston, TX) in talent and crew management, control room and Self Employed (Pilot)- Supervising Field Producer floor producing, and directing Magnolia / Red Productions (Dallas, TX) multiple cameras. Experienced in conducting and writing formal Supa Girlz (Season 1 Documentary)- Supervising Field Producer interviews and OTFs. Proficient in HBO MAX / Film-45 (Miami, FL) scheduling, budgeting, casting, Bride & Prejudice (Season 2)- Supervising Producer clearing locations, writing hot TLC/ Kinetic Content (Atlanta, GA) sheets, outlines, beat sheets, creative decks, show bibles, and Little Women Atlanta (Season 6)- Senior Field Producer any other pertinent production Lifetime/ Kinetic Content (Atlanta, GA) documents. Look Me in The Eye (Pilot)- Senior Field Producer OWN/ Kinetic Content (Los Angeles, CA) Digital proficiencies include Microsoft Office, Google Drive, The American Barbeque Showdown (Season 1)- Field Producer and Social Media platforms. Netflix/ All 3 Media (Atlanta, GA) Love Is Blind (Season 1)- Field Producer EDUCATION Netflix/ Delirium TV, LLC (Atlanta, GA) WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY, DETROIT MI 2006-2010 Teen Mom 2 (Season 16)- Field Producer Bachelor of Arts, Public Relations MTV/ MTV (Orlando, FL) Member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Inc. Beta Mu Chapter Married at First Sight: Honeymoon Island (Season 1)- Field Producer Lifetime/ Kinetic Content (Los Angeles, CA & St. -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

John Rasmussen [email protected] New York 917-331-3715 Offline/Online Editor Avid, Finalcut, Premiere

John Rasmussen [email protected] New York 917-331-3715 Offline/Online Editor Avid, FinalCut, Premiere fyi. Pilot Apr/May’16 Reality Editor BRAVO Tour Group S1 Airing May’16 Reality Editor DISCOVERY FAMILY Lost & Found w Mike and Jesse S1 Aired 2015 Reality Editor ANIMAL PLANET Restoration Wild S1 Aired 2015 Reality Editor HISTORY Best of Counting Cars S1 Aired 2015 Reality Editor Mortem Di Virgo June 2015 Short Film Editor HISTORY Best of Pawn Stars S1 Aired 2015 Reality Editor HGTV Flipping the Heartland S1 Aired 2015 Reality Editor A&E Lachey’s Bar S1 Aired 2015 DocuSeries Preditor HISTORY Counting Cars S4 Aired 2014 ‘15 Reality Preditor West of Her Mar -Aug ‘14 Feature Editor fyi. Tiny House Nation S1 Aired 2014 Reality Editor WGN America Wrestling with Death May 2014 Reality Sizzle Editor GAC Pilot Aired 2014 Reality Preditor FYI Tiny House Nation S1 Aired 2014 Reality Editor BRAVO Pilot May 2014 Reality Preditor E! Sizzle April 2014 Reality Editor FOOD NETWORK Pilot April 2014 Reality Preditor OXYGEN Pilot February 2014 Reality Preditor HISTORY Counting Cars S3 Aired 2014 Reality Preditor Milk&Strawberries March 2013 Short Film Editor / Post Sup. HISTORY We’re the Fugawis S1 Aired 2013 Reality Editor LIFETIME Celebrity Home Raiders S1 Aired March ’13 Reality Editor DISCOVERY Pilot February 2012 Reality Editor HISTORY Counting Cars S2 Aired 2012 ‘13 Reality Preditor HISTORY Cajun Pawn Stars S3 Aired 2012 ‘13 Reality Preditor LIFETIME Celebrity Home Raiders October 2012 Reality Pilot Editor UN WATCH Gala Video May 2012 Corporate -

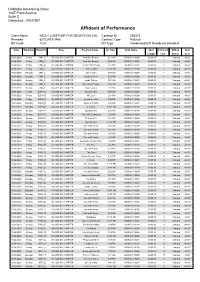

Affidavit of Performance

OnMedia Advertising Sales 1037 Front Avenue Suite C Columbus , GA31901 Affidavit of Performance Client Name KELLY LOEFFLER FOR SENATE/GA COL Contract ID 238373 Remarks 62722413-1456 Contract Type Political Bill Cycle 1/20 Bill Type Condensed EAI Broadcast Standard Date Weekday Network Zone Program Name Air Time Spot Name Spot Contract Billing Spot Length Line Status Cost 01/24/2020 Friday CNN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER New Day Berman 6:44 AM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/24/2020 Friday CNN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER New Day Berman 6:50 AM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/24/2020 Friday CNN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER Senate Trial Trump 6:31 PM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/24/2020 Friday CNN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER CNN Tonight 10:59 PM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/25/2020 Saturday CNN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER Smerconish 9:57 AM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/25/2020 Saturday CNN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER Situation Room 5:26 PM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/26/2020 Sunday CNN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER Inside Politics 7:51 AM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/26/2020 Sunday CNN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER State Union Tapper 9:28 AM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/26/2020 Sunday CNN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER Iowa Caucus 7:37 PM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/24/2020 Friday ESPN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER SportsCenter 6:57 AM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 5 Charged 48.00 * 01/24/2020 Friday ESPN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER NFL Live 2:01 PM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 5 Charged 48.00 * 01/24/2020 Friday ESPN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER Around the Horn 5:25 PM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 5 Charged 48.00 * 01/25/2020 Saturday ESPN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER Baylor at Florida 9:00 PM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 5 Charged 48.00 * 01/25/2020 Saturday ESPN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER X Games 11:36 PM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 5 Charged 48.00 * 01/26/2020 Sunday ESPN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER SportsCenter 6:25 AM GASKL 011620H 00:00:30 5 Charged 48.00 * 01/26/2020 Sunday ESPN_E GA-CBS MC CHARTER Post. -

Today's Television

54 TV TUESDAY DECEMBER 29 2020 Start the day Zits Insanity Streak lHAD~UCflA UNFORTUNATE::!.'(, t;HE: with a laugh TIMr;;:AT!-UN OL-DME'1VUR ... OW NoTM1NG MUCM, How are dogs like cell JUST $OCllL 1>1STlNC1NG ,.. phones? 1>.NI> YoO? They both have collar id. wHaT kind of key can never unlock a door? A monkey. Snake Tales Swamp I OON'"r -.HIN< -rHl:S Today’s quiz IS GOING "l"O SE. .. 1. is a monteith a type of bowl, cape or curtain? 291220 2. The tangelo is a hybrid of which two fruits? f fq()J/ 3. What is a farthingale? T oday’S TeleViSion 4. Which country is the nine SeVen abc SbS Ten world’s second largest oil 6.00 Today. 6.00 Sunrise. 8.00 Pre-Game 6.00 Cook And The Chef. (R) 6.00 WorldWatch. 10.30 German 6.00 Left Off The Map. 6.30 producer? 9.00 Today Extra Show. 9.00 Cricket. Second Test. 6.25 Short Cuts To Glory. News. 11.00 Spanish News. 11.30 Everyday Gourmet. 7.00 Ent. Summer. (PG) Australia v India. Day 4. Morning (R) 7.00 News. 10.00 David Turkish News. 12.00 Arabic News Tonight. 7.30 Judge Judy. (PG) 11.30 Morning News. session. 11.00 The Lunch Break. Attenborough’s Tasmania. (R) F24. (France) 12.30 ABC America: 8.00 Bold. (PG) 8.30 Studio 5. What does the Latin 12.00 MOVIE: Miss Pettigrew 11.40 Cricket. Australia v India. 11.00 Gardening Australia. (R) World News Tonight. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job. -

To Download The

FREE EXAM Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined Wellness Plans Extended Hours Multiple Locations www.forevervets.com4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA! ! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! September 24 - 30, 2020 INSIDE: has a new home at The latest House & Home THE LINKS! Listings Chris Rock gets 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 Page 21 Jacksonville Beach dramatic as Offering: · Hydrafacials ‘Fargo’ returns · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring Chris Rock stars in the Season 4 premiere · B12 Complex / of “Fargo” Sunday on FX. Lipolean Injections Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 www.SkinnyJax.com1 x 5” ad Now is a great time to It will provide your home: List Your Home for Sale • Complimentary coverage while the home is listed • An edge in the local market Kathleen Floryan LIST IT because buyers prefer to purchase a Broker Associate home that a seller stands behind • Reduced post-sale liability with [email protected] ListSecure® 904-687-5146 WITH ME! https://www.kathleenfloryan.exprealty.com BK3167010 I will provide you a FREE https://expressoffers.com/exp/kathleen-floryan America’s Preferred Ask me how to get cash offers on your home! Home Warranty for your home when we put it on the market. 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN FX brings Chris Rock to ‘Fargo’ for series’ fourth season What’s Available NOW Though the last visit to “Fargo” was a and pitched him what I wanted to do, and while ago, it’s still on the television map. -

Chapter 5 DATA COLLECTION TABLE of CONTENTS Page

August 1, 2007 TRAFFIC ENGINEERING MANUAL Chapter 5 DATA COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 5-1.00 INTRODUCTION . .5-5 1.01 Purpose 1.02 Scope 1.03 Chapter Organization 5-2.00 GLOSSARY . .5-5 5-3.00 VOLUME COUNTS . .5-9 3.01 Types of Traffic Counts 3.02 Regularly Conducted Counts 3.03 Equipment 3.04 Field Data Collection 3.05 Data Recording Forms 3.06 Sample Sizes 3.07 Computations 3.08 Uses of Volume Counts 5-4.00 SPOT SPEED . .5-16 4.01 Equipment 4.02 Field Data Collection 4.03 Data Recording Forms 4.04 Sample Size 4.05 Computations 4.06 Uses of Sport Speed Data 5-5.00 TRAVEL TIME AND DELAY . .5-17 5.01 Types of Delay Studies 5.02 Equipment 5.03 Field Data Collection 5.04 Data Recording Forms 5.05 Sample Size 5.06 Computations 5.07 Uses of Travel/Delay Studies 5-6.00 VEHICLE OCCUPANCY . .5-21 6.01 Equipment 6.02 Field Data Collection 6.03 Data Recording Forms 6.04 Sample Size 6.05 Computations 6.06 Uses of Vehicle Occupancies 5-1 August 1, 2007 TRAFFIC ENGINEERING MANUAL Page 5-7.00 LANE OCCUPANCY . .5-22 7.01 Equipment 7.02 Field Data Collection 7.03 Data Recording Forms 7.04 Sample Size 7.05 Computations 7.06 Uses of Lane Occupancies 5-8.00 VEHICLE DENSITY . .5-23 8.01 Equipment 8.02 Field Data Collection 8.03 Data Recording Forms 8.04 Sample Size 8.05 Computations 8.06 Uses of Vehicle Densities 5-9.00 QUEUE STUDIES . -

Counting Cars

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE HISTORY® Revs Up for More Wheeling and Dealing When Danny ‘The Count’ Koker Returns to the Driver’s Seat for an All-New Season of… COUNTING CARS New York, NY – His name is The Count, and his game is one-of-a-kind, customized classic cars and motorcycles. Danny “The Count” Koker doesn’t just love hot rods and choppers. He lives for them. Whether it’s a ’63 Corvette, a classic Thunderbird, a muscle-bound Trans Am, or a yacht-sized Caddy, he knows these high-performance beauties inside and out. What’s more, he’ll do anything it takes to get his hands on those he likes – he’s known for pulling over cars he passes on the road and offering cash for them on the spot, or for using a retailer’s PA system to lure a car owner back to the parking lot to make a deal – and then “flip” them for a profit. Danny and the crew from Count’s Kustoms, his Vegas-based auto repair business, are behind the wheel again for a new season of COUNTING CARS, premiering Tuesday, April 9 at 9pm ET on HISTORY. The heat is on as the boys buy, trick out and re-sell classic cars, bikes and more. Danny is obsessed, so the more rides he buys, the faster they have to move to keep Count’s Kustoms in business. This season’s projects span all eras of cars, trucks, bikes and trikes. They’ll be working with Ziggy Marley to restore and customize Bob Marley’s last car, a 1980 Mercedes 500SL Euro; and customizing a soap box derby car for a youngster. -

TALENT CASTING/DEVELOPMENT a Royal Wedding Special (Snapchat +TLC) Watercooler Casting

TALENT CASTING/DEVELOPMENT A Royal Wedding Special (Snapchat +TLC) Watercooler Casting Group 9 Drag Me Down The Aisle (TLC) Watercooler Casting ALXEMY X Casting & Host Development Watercooler Casting Group 9-Thrillist, Dodo, & Seeker Trekenomics & Snow Day Watercooler Casting Travel Channel Ancient Beasts (Travel Channel) Watercooler Casting Arrow Media Gatherings (Reese Witherspoon/WT) Watercooler Casting Part2Pictures In Bed With Simon Watercooler Casting FYI A Mans World (Bravo) Watercooler Casting Lucky 8 Zooborns (Animal Planet) Watercooler Casting MY Entertainment Ice Age Live (Animal Planet) Watercooler Casting Renegade Times Square 24/7 (Travel Channel) Watercooler Casting Departure Films Love Sick (Lifetime) Watercooler Casting Big Apple Productions Blind Partners (Spike) Watercooler Casting Blackfin Teenprenuer (Lifetime) Watercooler Casting Lincoln Square Studios Miami Flips (Gabrielle Union/HGTV) Watercooler Casting Deaprture Films A&E Character PitchFest 2016 Watercooler Casting A&E Networks Mysteries of Jamaica Watercooler Casting Switchblade Entertainment WT “Swirled” (VH1) Watercooler Casting Left/Right & Superb Entertainment “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles” (Travel) Watercooler Casting Switchblade Entertainment “Sh*t We Don’t Talk About” (Science Channel) Watercooler Casting MY Entertainment “My Crazy Kids” (TLC) Watercooler Casting Back2Back “The Audience” (Bravo) Watercooler Casting ITV “Amazon Women” (Lifetime) Watercooler Casting Watercooler Casting/Mike TV “Autopsy Girls” (Oxygen) Watercooler Casting GRB Multiple Development Project(s) Watercooler Casting ITV (Consulting/Retainer) Untitled DIY Development Project Watercooler Casting Back Roads Entertainment “Restorative Justice” (A&E) Watercooler Casting Citizen Jones 2015 Spike Casting Pitch Fest Watercooler Casting Spike “Coming to America” (BBC) Watercooler Casting Voltage TV “Unlisted” (ABC Family) Watercooler Casting Lincoln Studios “Reaching For Heaven” (Oxygen) Watercooler Casting EOne “Boots of Glory” (Tru) Watercooler Casting Jane St. -

O.305.438.9200 - [email protected]

404 Washington Ave., Suite 730 - Miami Beach, FL 33139- o.305.438.9200 - [email protected] IF VOLUME 113, No.309 FACEBOOK.COM/MIAMIHERALD WINNER OF 20 Early storms TUESDAY JULY192016 $1 STAY CONNECTED MIAMIHERALD.COM TWITTER.COM/MIAMIHERALD PULITZER PRIZES 91°/79° See 4B H1 WORLD SCRUTINY ON IRAN NUCLEAR DEAL Documents obtained by the AP show that nuclear limits imposed on Iran will start to ease before the accord expires. 12A TROPICAL LIFE OLYMPIC SPLASH FOR FOOTVOLLEY? In footvolley — a new demonstration sport at the Rio Olympics — you can’t use your hands to get the ball over the net, but you JOHN LOCHER AP Illinois delegate Christian Gramm, left, and other delegates react as some call for a roll call vote on the adoption of the rules Monday at the can use your feet. 1C Republican National Convention in Cleveland. ‘Hold the vote!’ the anti-Trump faction chanted. ‘Roll call!’ Their microphones were shut off. CAMPAIGN 2016 | REPUBLICAN NATIONAL CONVENTION Trump’s law-and-order night preceded by a day of chaos delegates tried one last time to insurrection withdrew — appar- SPORTS ........................................................ BY PATRICIA MAZZEI prevent Donald Trump from ently pressured by party leaders Political unrest marked the [email protected] winning the GOP’s presi- who didn’t want to be embar- FINS SIGN FOSTER first day of the Republican dential nomination. rassed. The maneuver led to National Convention CLEVELAND They amassed raucous protests on the con- TO 1-YEAR DEAL ........................................................ It was supposed to be law-and- enough support to The Dolphins signed It culminated with a order night at the Republican force a full vote of SEE CONVENTION, 2A veteran running back Arian last-ditch protest by National Convention. -

TV Listings FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2015

TV listings FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2015 04:00 10 Years-PG15 13:45 Mini Ninjas 06:00 Grace Unplugged-PG 14:10 The 7D 08:00 Quartet-PG15 14:35 Penn Zero: Part Time Hero 10:00 Planet 51-PG 15:00 Mighty Med 12:00 The Gabby Douglas Story-PG 15:25 Supa Strikas 13:45 Iron Man-PG15 15:55 Kickin’ It 16:00 Quartet-PG15 16:20 Lab Rats 18:00 The Monuments Men-PG15 16:45 Kirby Buckets 20:00 The Grand Budapest Hotel 17:10 Phineas And Ferb 22:00 Not Safe For Work-PG15 17:40 Japaneezi Going Going Gong 18:05 Super Matrak 18:30 Ultimate Spider-Man 19:00 Lab Rats 19:25 Kickin’ It 19:50 Phineas And Ferb 20:10 Phineas And Ferb 01:30 Barricade 20:20 Boyster 03:00 The Four 21:00 Programmes Start At 05:00 Another Year 6:00am KSA 07:15 One Day 09:00 The Station Agent 10:30 All Hat 12:00 Barricade 13:30 Flightplan 15:15 Picture Claire 16:45 Beyond A Reasonable Doubt 18:30 Death At A Funeral 20:00 Bad Company Nat Geo Wild HD 22:00 Legendary 01:45 World’s Weirdest 23:45 Dawn Of The Dead 02:40 The Great Serengeti 03:35 Speed Kills 04:30 Touching The Dragon 05:25 World’s Weirdest MAN OF TAI CHI ON OSN MOVIES ACTION HD 06:20 Wild 24 07:15 World’s Deadliest Riders Of Berk 06:53 Prototype This 10:35 Sheriff Callie’s Wild West 08:10 The Kangaroo King 00:00 Grey’s Anatomy 08:20 Total Drama: Pahkitew 07:38 Food Factory 11:00 Sofia The First 09:05 Valley Of The Wolves 01:00 MasterChef - The Island 08:01 Food Factory 11:30 Henry Hugglemonster 10:00 Monster Fish Professionals 08:40 Johnny Test 08:23 Mind Control Freaks 12:00 Doc McStuffins 10:55 Wild Wild West 02:00 The Listener