Expert Committee Appointed by The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

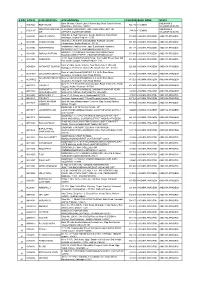

Grama/Ward Sachivalayam Recruitment (Sports Quota) 01/2020

Grama/Ward Sachivalayam Recruitment (Sports Quota) 01/2020 Provisional Priority list As per G.O.Ms.No. 74 YAT&C (Sports) Department, Government of A.P For the post :- Mahila Police Kurnool District Forms Genuinene DISCIPLINE Team/ Priority given Submitted ss HALL TICKET Name of the Remarks if S.No As per Level of Particiption and Backup Individual As per As per Confirmati NO Candidate any Annexure -I Annexure -II Annexure - on III (Yes/No) Participated in 29th National Senior Taekwondo Championship U-62 Weight Catagery held at District Sports Complex New Sarkanda, Vilaspur Chhattisgarh from 20th THUMMALA to 22th October 2010. 1 201101008041 PALLI TAEKWONDA I 27 Form-II Back up: Participated in 29th AP State Senior Inter District KRISHNAVENI Taekwondo Championship held at Sri Sri Function Hall Madhurawada, Visakhapatnam from 4th to 6th September 2010 Secured Gold Medal. Partcipated in 52nd Senior National Basketball Championships Men & Women held at Ludhina, Punjab from 5th to 12th March 2002. 2 201201000421 K SIREESHA BASKETBALL Back up: Participated in XXV AP Inter District Basketball T 27 Form - II Yes Championship Men & Women held at Anantapurmu from 05th to 08th December 2001 Secured Runners. For the post :- Mahila Police Kurnool District Forms Genuinene DISCIPLINE Team/ Priority given Submitted ss HALL TICKET Name of the Remarks if S.No As per Level of Particiption and Backup Individual As per As per Confirmati NO Candidate any Annexure -I Annexure -II Annexure - on III (Yes/No) Participated in 40th Senior Women National Handball Championship held at Delhi from 4th to 9th January 2012. State Back up: Participated in 41th AP State Senior Women Certificate DHARMAKARI Form - II & 3 201301022614 HANDBALL Handball Championship held at RGM Engineering College T 27 Yes genuinity INDRAJA IV Nandyal from 17th to 19th December 2011 Secured not Runners. -

Srikakulam-DDMP-Volume I Genral Plan and HVCA Report

District Disaster Management Plan Srikakulam Volume I – General Plan and Hazard Vulnerability and Capacity Analysis Prepared by: District Administration, Srikakulam Supported by: UNDP, Andhra Pradesh Contents 1. The Introduction: ......................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. The Objectives of the Plan: ..................................................................................................... 6 1.2. Approach: ................................................................................................................................ 6 1.3. Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.4. HOW TO USE THIS PLAN ......................................................................................................... 9 1.5. Scope and Ownership of District Disaster Management Plan: ............................................. 10 1.6. Monitoring, evaluation and update of the Plan ................................................................... 11 1.6.1.1. Review and update ................................................................................................... 12 1.6.1.2. Evaluation of the Plan ............................................................................................... 13 2. The Implementation of the District Disaster Management Plan ........................................ 16 2.1. Disaster Management Authorities ...................................................................................... -

Operations and Maintanence Syetems for Metro Railways

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT OF THE SUB-COMMITTEE ON OPERATIONS AND MAINTANENCE SYETEMS FOR METRO RAILWAYS NOVEMBER 2013 Sub-Committee on Operation & Maintenance Practices Ministry of Urban Development Final Report PREFACE 1) In view of the rapid urbanization and growing economy, the country has been moving on the path of accelerated development of urban transport solutions in cities. The cities of Kolkata, Delhi and Bangalore have setup Metro Rail System and are operating them successfully. Similarly the cities of Mumbai, Hyderabad and Chennai are constructing Metro Rail system. Smaller cities like Jaipur, Kochi and Gurgaon too are constructing Metro Rail system. With the new policy of Central Government to empower cities and towns with more than two million population With Metro Rail System, more cities and towns are going to plan and construct the same. It is expected that by the end of the Twelfth Five Year Plan, India will have more than 400 Km of operational metro rail network (up from present 223 Km Approximate). The National Manufacturing Competitiveness Council (NMCC) has been set up by the Government of India to provide a continuing forum for policy dialogue to energise and sustain the growth of manufacturing industries in India. A meeting was organized by NMCC on May 03, 2012 and one of the agenda items in that meeting was “Promotion of Manufacturing for Metro Rail System in India as well as formation of Standards for the same”. In view of the NMCC meeting and heavy investments planned in Metro Rail Systems, Ministry of Urban Development (MOUD) has taken the initiative of forming a Committee for “Standardization and Indigenization of Metro Rail Systems” in May 2012. -

How the Kurnool District in Andhra Pradesh, India, Fought Corona (Case Study)

Dobe M, Sahu M. How the Kurnool district in Andhra Pradesh, India, fought Corona (Case study). SEEJPH 2020, posted: 18 November 2020. DOI: 10.4119/seejph-3963 CASE STUDY How the Kurnool district in Andhra Pradesh, India, fought Corona Madhumita Dobe1, Monalisha Sahu1 1 Department of Health Promotion and Education, All India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health, West Bengal, India. Corresponding author: Madhumita Dobe; Address: 110, Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolkata - 700073, West Bengal, India; Telephone: +9830123754; Email:[email protected] P a g e 1 | 9 Dobe M, Sahu M. How the Kurnool district in Andhra Pradesh, India, fought Corona (Case study). SEEJPH 2020, posted: 18 November 2020. DOI: 10.4119/seejph-3963 Abstract Background: Kurnool, one of the four districts in the Rayalaseema region of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, emerged as a COVID-19 hotspot by mid-April 2020. Method: The authors compiled the publicly available information on different public health measures in Kurnool district and related them to the progression of COVID-19 from March to May 2020. Results: Two surges in pandemic progression of COVID-19 were recorded in Kurnool. The ini- tial upsurge in cases was attributed to return of people from other Indian states, along with return of participants of a religious congregation in Delhi, followed by in-migration of workers and truckers from other states and other districts of Andhra Pradesh, particularly from the state of Maharashtra (one of the worst affected states in India) and Chennai (the Koyambedu wholesale market - epicenter of the largest cluster of COVID-19 in Tamil Nadu). -

03404349.Pdf

UA MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT STUDY GROUP Jagdish M. Bhagwati Nazli Choucri Wayne A. Cornelius John R. Harris Michael J. Piore Rosemarie S. Rogers Myron Weiner a ........ .................. ..... .......... C/77-5 INTERNAL MIGRATION POLICIES IN AN INDIAN STATE: A CASE STUDY OF THE MULKI RULES IN HYDERABAD AND ANDHRA K.V. Narayana Rao Migration and Development Study Group Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 August 1977 Preface by Myron Weiner This study by Dr. K.V. Narayana Rao, a political scientist and Deputy Director of the National Institute of Community Development in Hyderabad who has specialized in the study of Andhra Pradesh politics, examines one of the earliest and most enduring attempts by a state government in India to influence the patterns of internal migration. The policy of intervention began in 1868 when the traditional ruler of Hyderabad State initiated steps to ensure that local people (or as they are called in Urdu, mulkis) would be given preferences in employment in the administrative services, a policy that continues, in a more complex form, to the present day. A high rate of population growth for the past two decades, a rapid expansion in education, and a low rate of industrial growth have combined to create a major problem of scarce employment opportunities in Andhra Pradesh as in most of India and, indeed, in many countries in the third world. It is not surprising therefore that there should be political pressures for controlling the labor market by those social classes in the urban areas that are best equipped to exercise political power. -

LHA Recuritment Visakhapatnam Centre Screening Test Adhrapradesh Candidates at Mudasarlova Park Main Gate,Visakhapatnam.Contact No

LHA Recuritment Visakhapatnam centre Screening test Adhrapradesh Candidates at Mudasarlova Park main gate,Visakhapatnam.Contact No. 0891-2733140 Date No. Of Candidates S. Nos. 12/22/2014 1300 0001-1300 12/23/2014 1300 1301-2600 12/24/2014 1299 2601-3899 12/26/2014 1300 3900-5199 12/27/2014 1200 5200-6399 12/28/2014 1200 6400-7599 12/29/2014 1200 7600-8799 12/30/2014 1177 8800-9977 Total 9977 FROM CANDIDATES / EMPLOYMENT OFFICES GUNTUR REGISTRATION NO. CASTE GENDER CANDIDATE NAME FATHER/ S. No. Roll Nos ADDRESS D.O.B HUSBAND NAME PRIORITY & P.H V.VENKATA MUNEESWARA SUREPALLI P.O MALE RAO 1 1 S/O ERESWARA RAO BHATTIPROLU BC-B MANDALAM, GUNTUR 14.01.1985 SHAIK BAHSA D.NO.1-8-48 MALE 2 2 S/O HUSSIAN SANTHA BAZAR BC-B CHILAKURI PETA ,GUNTUR 8/18/1985 K.NAGARAJU D.NO.7-2-12/1 MALE 3 3 S/O VENKATESWARULU GANGANAMMAPETA BC-A TENALI. 4/21/1985 SHAIK AKBAR BASHA D.NO.15-5-1/5 MALE 4 4 S/O MAHABOOB SUBHANI PANASATHOTA BC-E NARASARAO PETA 8/30/1984 S.VENUGOPAL H.NO.2-34 MALE 5 5 S/O S.UMAMAHESWARA RAO PETERU P.O BC-B REPALLI MANDALAM 7/20/1984 B.N.SAIDULU PULIPADU MALE 6 6 S/O PUNNAIAH GURAJALA MANDLAM ,GUNTUR BC-A 6/11/1985 G.RAMESH BABU BHOGASWARA PET MALE 7 7 S/O SIVANJANEYULU BATTIPROLU MANDLAM, GUNTUR BC-A 8/15/1984 K.NAGARAJENDRA KUMAR PAMIDIMARRU POST MALE 8 8 S/O. -

List-Of-TO-STO-20200707191409.Pdf

Annual Review Report for the year 2018-19 Annexure 1.1 List of DTOs/ATOs/STOs in Andhra Pradesh (As referred to in para 1.1) Srikakulam District Vizianagaram District 1 DTO, Srikakulam 1 DTO, Vizianagaram 2 STO, Narasannapeta 2 STO, Bobbili 3 STO, Palakonda 3 STO, Gajapathinagaram 4 STO, Palasa 4 STO, Parvathipuram 5 STO, Ponduru 5 STO, Salur 6 STO, Rajam 6 STO, Srungavarapukota 7 STO, Sompeta 7 STO, Bhogapuram 8 STO, Tekkali 8 STO, Cheepurupalli 9 STO, Amudalavalasa 9 STO, Kothavalasa 10 STO, Itchapuram 10 STO, Kurupam 11 STO, Kotabommali 11 STO, Nellimarla 12 STO, Hiramandalam at Kothur 12 STO, Badangi at Therlam 13 STO, Pathapatnam 13 STO, Vizianagaram 14 STO, Srikakulam East Godavari District 15 STO, Ranasthalam 1 DTO, East Godavari Visakhapatnam District 2 STO, Alamuru 1 DTO, Visakhapatnam 3 STO, Amalapuram 2 STO, Anakapallli (E) 4 STO, Kakinada 3 STO, Bheemunipatnam 5 STO, Kothapeta 4 STO, Chodavaram 6 STO, Peddapuram 5 STO, Elamanchili 7 DTO, Rajahmundry 6 STO, Narsipatnam 8 STO, R.C.Puram 7 STO, Paderu 9 STO, Rampachodavaram 8 STO, Visakhapatnam 10 STO, Rayavaram 9 STO, Anakapalli(W) 11 STO, Razole 10 STO, Araku 12 STO, Addateegala 11 STO, Chintapalli 13 STO, Mummidivaram 12 STO, Kota Uratla 14 STO, Pithapuram 13 STO, Madugula 15 STO, Prathipadu 14 STO, Nakkapalli at Payakaraopeta 16 STO, Tuni West Godavari District 17 STO, Jaggampeta 1 DTO, West Godavari 18 STO, Korukonda 2 STO, Bhimavaram 19 STO, Anaparthy 3 STO, Chintalapudi 20 STO, Chintoor 4 STO, Gopalapuram Prakasam District 5 STO, Kovvur 1 ATO, Kandukuru 6 STO, Narasapuram -

List of Courtwise Bluejeans Ids and Passcodes in Krishna District 238

List of Courtwise Bluejeans IDs and Passcodes in Krishna District 5937525977 3261 1 Prl. District & Sessions Court, Krishna at Machilipatnam 2 I Addl. District Court, Machilipatnam 842 119 875 9 5504 II Addl. District Court, Krishna atVijayawada-cum- 538 785 792 7 1114 3 Metropolitan SessionsCourt at ,Vijayawada 311 358 517 7 3033 Spl. Judge for trial of cases under SPE & ACB-cum-III 4 Addl. District and Sessions Judge, Krishna at Vijayawada - cum-Addl. Metropolitan Sessions Court at ,Vijayawada Family Court-cum-IV Addl. District & Sessions Court, 7694386088 7525 5 Krishna at ,Vijayawada Mahila Court in the cadre of Sessions Judge –cum-V Addl. 482 741 622 0 8184 6 Dist. Sessions Court ,Vijayawada VI Addl. District & Sessions Court, Krishna (FTC), 590 857 849 4 7065 7 Machilipatnam VII Addl. District & Sessions Court, Krishna (FTC), 242 806 244 0 3116 8 Vijayawada VIII Addl. District and Sessions Court (FTC),Krishna at 324 248 605 5 4183 9 Vijayawada 10 IX-A.D.J.-cum-II-A.M.S.J. Court, Machilipatnam 448 887 050 7 4714 Spl. Sessions Court for trail of cases filed under SCs & STs 480 235 460 9 3240 11 (POA) Act, 1989-cum- X Additional District and Sessions Court ,Machilipatnam 12 XI Additional District Judge, Gudivada 456 613 601 5 2522 13 XII Addl. District Judge, Vijayawada 351 655 494 5 3868 14 XIII Addl. District Judge, Vijayawada 4124289203 3447 15 XIV Addl. District Judge, Vijayawada 7812770254 6990 16 XV Addl. District Judge, Nuzvid 4404009687 5197 17 XVI Addl. District Judge , Nandigama 4314769870 9309 18 Spl. -

Public Private Partnership Projects in India Compendium of Case Studies

Government of India Ministry of Finance Department of Economic Affairs Public Private Partnership Projects in India Compendium of Case Studies c Government of India Ministry of Finance Department of Economic Affairs Public Private Partnership Projects in India Compendium of Case Studies December 2010 Compendium of Case Studies Public Private Partnership projects in India Public Private Partnership projects © Department of Economic Affairs All rights reserved Published by: PPP Cell, Department of Economic Affairs Ministry of Finance, Government of India New Delhi-110 001, India www.pppinindia.com Disclaimer This Compendium of Case Studies has been prepared as a part of a PPP capacity building programme that is being developed by the Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India (DEA) with funding support from the World Bank, AusAID South Asia Region Infrastructure for Growth Initiative and the Public Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF). A consulting consortium, consisting of Economic Consulting Associates Limited (ECA) and CRISIL Risk and Infrastructure Solutions Limited (CRIS), commissioned by the World Bank, has prepared this compendium based on extensive external consultations. ECA and CRIS have taken due care and caution in preparing the contents of this compendium. The accuracy, adequacy or completeness of any information contained in this toolkit is not guaranteed and DEA, World Bank, AusAID, PPIAF, ECA or CRIS are not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for the results obtained from the use of such information. The contents of this compendium should not be construed to be the opinion of the DEA, World Bank, AusAID or PPIAF. DEA is not liable for any direct, indirect, incidental or consequential damages of any kind whatsoever to the subscribers / users / transmitters / distributors of this toolkit. -

Police Matters: the Everyday State and Caste Politics in South India, 1900�1975 � by Radha Kumar

PolICe atter P olice M a tte rs T he v eryday tate and aste Politics in South India, 1900–1975 • R a dha Kumar Cornell unIerIt Pre IthaCa an lonon Copyright 2021 by Cornell University The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https:creativecommons.orglicensesby-nc-nd4.0. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New ork 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 2021 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kumar, Radha, 1981 author. Title: Police matters: the everyday state and caste politics in south India, 19001975 by Radha Kumar. Description: Ithaca New ork: Cornell University Press, 2021 Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021005664 (print) LCCN 2021005665 (ebook) ISBN 9781501761065 (paperback) ISBN 9781501760860 (pdf) ISBN 9781501760877 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Police—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Law enforcement—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste— Political aspects—India—Tamil Nadu—History. Police-community relations—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste-based discrimination—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HV8249.T3 K86 2021 (print) LCC HV8249.T3 (ebook) DDC 363.20954820904—dc23 LC record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005664 LC ebook record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005665 Cover image: The Car en Route, Srivilliputtur, c. 1935. The British Library Board, Carleston Collection: Album of Snapshot Views in South India, Photo 6281 (40). -

DISTRICT PRIMARY EDUCATION Programvffi-Phasf!

DISTRICT PRIMARY EDUCATION PROGRAMvffi-PHASf!:: (A m ovem ent,for^ "^<n u. Chirtocpr DisTfiC|f DISTRICT'gptJCATION '1998-2003 CKITTOOR DISTRIC ANDHRA FRADESK f t - C6Mny & UOCUMfflffrflON CtNTB' 'lijticziil TnstitEducatico;^! ^ {i g a nd ni»tt at ion. ^ Aifr^indo Mar*, s < ^ . INDEX S.No Chapter Page No. 1. Vision for DPEP : Chittoor District 01-04 2. About the District 05-07 3. District situational analysis - Educational scenario 08-15 4. Enrollment - Drop outs - Retention 16-22 5. Equity 23-31 6. Key issues and concerns 32-38 7. Access 39-46 8. Quality in education 47-55 9. Planning process 56-62* 10. Management structures 63-71 11. Community participation in DPEP 72-74 12. Educational Plan & Cost Estimates 75-99 APPENDIX NJEPA DC D09752 CHAPTER - I VISION FOR DPEP : CHITTOOR DISTRICT •liducaiion for All' is a compelling goal because education improves both the lives of children and the economic and social development of the nation. A child who has access to quality primary schooling has a better chance in life. Learning to read, to wxite and to do basic arithmetic provides a foundation for continued learning through out life. Also important are the life skills that education gives to children. Education gives a child a better chance for a full, healthy and secure life. The education system in our country has made great efforts in providing primarv’ education to substantial numbers for the last five decades. Yet, the system failed in two wavs. System failed to reach some children (children in the school less habitations, working and street children, Girls with daily responsibilities. -

S No Atm Id Atm Location Atm Address Pincode Bank

S NO ATM ID ATM LOCATION ATM ADDRESS PINCODE BANK ZONE STATE Bank Of India, Church Lane, Phoenix Bay, Near Carmel School, ANDAMAN & ACE9022 PORT BLAIR 744 101 CHENNAI 1 Ward No.6, Port Blair - 744101 NICOBAR ISLANDS DOLYGUNJ,PORTBL ATR ROAD, PHARGOAN, DOLYGUNJ POST,OPP TO ANDAMAN & CCE8137 744103 CHENNAI 2 AIR AIRPORT, SOUTH ANDAMAN NICOBAR ISLANDS Shop No :2, Near Sai Xerox, Beside Medinova, Rajiv Road, AAX8001 ANANTHAPURA 515 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 3 Anathapur, Andhra Pradesh - 5155 Shop No 2, Ammanna Setty Building, Kothavur Junction, ACV8001 CHODAVARAM 531 036 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 4 Chodavaram, Andhra Pradesh - 53136 kiranashop 5 road junction ,opp. Sudarshana mandiram, ACV8002 NARSIPATNAM 531 116 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 5 Narsipatnam 531116 visakhapatnam (dist)-531116 DO.NO 11-183,GOPALA PATNAM, MAIN ROAD NEAR ACV8003 GOPALA PATNAM 530 047 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 6 NOOKALAMMA TEMPLE, VISAKHAPATNAM-530047 4-493, Near Bharat Petroliam Pump, Koti Reddy Street, Near Old ACY8001 CUDDAPPA 516 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 7 Bus stand Cudappa, Andhra Pradesh- 5161 Bank of India, Guntur Branch, Door No.5-25-521, Main Rd, AGN9001 KOTHAPET GUNTUR 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta, P.B.No.66, Guntur (P), Dist.Guntur, AP - 522001. 8 Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW8001 GAJUWAKA BRANCH 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 9 Gajuwaka, Anakapalle Main Road-530026 GAJUWAKA BRANCH Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW9002 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH