HS2 Public Consultation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Aylesbury Vale

Appendix A DISTRICT OF AYLESBURY VALE REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE ACT, 1983 LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 1972 AYLESBURY PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY SCHEDULE OF POLLING DISTRICTS AND POLLING PLACES The Aylesbury Vale District Council has designated the following Polling Districts and Polling Places for the Aylesbury Parliamentary Constituency. These Polling Districts and Polling Places will come into effect following the making of The Aylesbury Vale (Electoral Changes) Order 2014. The Polling District is also the Polling Place except where indicated. The same Polling Districts and Polling Places will also apply for local elections. Whilst indicative Polling Stations are shown it is for the Returning Officer for the particular election to determine the location of the Polling Station. Where a boundary is described or shown on a map as running along a road, railway line, footway, watercourse or similar geographical feature, it shall be treated as running along the centre line of the feature. Polling District/Description of Polling Polling Place Indicative Polling District Station Aylesbury Baptist Church, Bedgrove No. 1 Limes Avenue That part of the Bedgrove Ward of Aylesbury Town to the north of a line commencing at Tring Road running south-westwards from 2 Bedgrove to the rear of properties in Bedgrove and Camborne Avenue (but reverting to the road where there is no frontage residential property) to Turnfurlong Lane, thence north-westwards along Turnfurlong Lane to the north-western boundary of No. 1A, thence north-eastwards along the rear boundary of 1 – 14 Windsor Road and 2 – 4 Hazell Avenue to St Josephs RC First School, thence following the south- eastern and north-eastern perimeter of the school site to join and follow the rear boundary of properties in King Edward Avenue, thence around the south-eastern side of 118 Tring Road to the Ward boundary at Tring Road. -

Coldharbour News Coldharbour News

www.coldharbour-pc.gov.uk Coldharbour News The Coldharbour Parish Council Newsletter OctoberJanuary 2014 Pictures of Fair in the Square and Fairford Leys Dog Show inside Published by Coldharbour Parish Council Volume 9 issue 3 Coldharbour Parish News Your Coldharbour Who deals with what? are being urged to park at the main car Dog Mess Again!! Parish Councillors The Parish Council were informed recently park in the village centre and walk to We are sorry that some people are expressing concerns the school during this time. to have to Chairman about local issues on social media sites and keep repeating Planning and Permitted Cllr Andrew Cole whilst people are voicing their opinions – this but it is Development - Ernest Cook Tel. 01296 334651 they are not contacting the relevant bodies one of the such as the Police and Parish Council to biggest issues [email protected] Covenants report them. All councillors agreed that Just a reminder to all residents that you that concern Vice Chairman people need to take responsibility and must seek separate approval from the residents. The report matters to the relevant authority Parish Council Cllr Sally Pattinson Parish Council on any changes you make to to deal with rather than complaining on a your property even if you have been given are not Tel. 01296 331822 This area has always been known as ‘the social media site. Failing to report concerns planning permission or your changes are responsible [email protected] or specific problems means those able to main play area’ and when the improvements for cleaning up have been completed we feel that it would considered to be “Permitted Development”. -

October 2019 Keen Close Friday 7Th February 2020 Fairford Leys Aylesbury Friday 22Nd May 2020 9:30AM —10:30AM 01296 482094 Ring the School Office for More Information

www.coldharbour-pc.gov.uk Coldharbour News The Coldharbour Parish Council Newsletterwww.coldharbour-pc.gov.uk OctoberJanuary 20192014 See inside for: Pictures of community events The British Army and Fairford Leys Dates of Forthcoming Events Volume 14 issue2 Coldharbour Parish Council News Your Coldharbour Forthcoming Parish Council Community Events Parish Councillors Annual Remembrance Service Christmas in the Square Chairman Sunday10th November Saturday7th December Cllr Adam Poland This celebration of Christmas starts at 5pm Tel. 01296 291070 with community singing led by Aylesbury [email protected] Concert Band; followed by Christmas Vice Chairman Carols and an Outdoor Nativity presented by the Church on Fairford Leys. Hopefully, Cllr Sally Pattinson after this a loud rendition of Jingle Bells will Tel. 01296 331822 point Father Christmas in the right direction [email protected] for the square. This is a free council Cllr Steven Lambert sponsored event and every child will meet Tel. 01296 338387 Santa and receive a bag of sweets kindly [email protected] donated by Fairford Leys WI. Cllr Andrew Cole Tel. 01296 334651 [email protected] Cllr Caroline Baughan The event starts at 10:30 am in the Church Tel. 01296 331532 on Fairford Leys. All are welcome to attend [email protected] this special service or to assemble in the Cllr Sally-Ann Jarvis Square at 11:00am for the Two Minute Tel. 07585 613009 Silence, followed by a short Service of [email protected] Remembrance in honour of those who have given their lives in service of their Cllr Sarah James country. Wreaths will be laid by Chairman of Tel. -

Download the Case Study

Sustainable Travel Publicity Case Study - Buckinghamshire County Council The Challenge - Create a fl exible base map showing sustainable modes of travel, which can be used to create a wide range of printed leafl ets and online solutions. Buckinghamshire County Council has published a variety of maps to promote sustainable travel, but due to reduced resources and budgets the sustainable travel team were keen to move to a solution which streamlined the production of future mapping products. the solution Pindar Creative has mapped the county of Buckinghamshire using GIS data in a user friendly style. The base map To Wingrave and Leighton Buzzard shows all sustainable modes of travel includingTo Wing, Leighton Buzzard and Milton Keyne s cycle, train and bus routes. This base map is very fl exible and can Watermead Bierton To Wing and Milton Keynes To Bicester, Steeple Claydon and Quainton To Aylesbury Vale Parkway= and Berryfields be used for a wide range of products including printed maps, leafl ets and online solutions, see leafl et and wallchart Quarrendon examples below: Meadowcroft Haydon Elmhurst Hill A V A I C E S S L Y R R A C F S U 6 W M P S G B E A R A N U E R E The A R D N R L S T 6 T D T E O D C X RI D 4 VE C O R R W IN R A L O O G T W L C A Based on Bartholomews mapping. Reproduced by permission H T 60 D O T MO A N A T C A O R Y P C E S R E A A T 165 ToTo WingraveWingrave andand LeightonLeighton BuzzardBuzzard ASE L L E L E O L R D W T A I R N P of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., Bishopbriggs, Glasgow. -

Aylesbury Historic Town Assessment Draft Report 79

Aylesbury Historic Town Assessment Draft Report Figure 44: Morphology of Aylesbury 79 Aylesbury Historic Town Assessment Draft Report Figure 45: period development 80 Aylesbury Historic Town Assessment Draft Report 5 Historic Urban Zones 5.1 Introduction The process of characterising and analysing Buckinghamshire towns produces a large quantity of information at a ‘fine-grained scale’ e.g. the character of particular buildings, town plan forms and location of archaeological data. This multitude of information can be hard to assimilate. In order to distil this information into an understandable form, the project defines larger areas or Historic Urban Zones (HUZs) for each town; these zones provide a framework for summarising information spatially and in written form ( 81 Aylesbury Historic Town Assessment Draft Report Figure 47). Each zone contains several sections including: A summary of the zone including reasons for the demarcation of the zone. An assessment of the known and potential archaeological interest for pre 20th century areas only. An assessment of existing built character. 5.2 Historic Urban Zones The creation of these zones begins with several discrete data sets including historical cartography and documentary sources; known archaeological work; buildings evidence (whether listed or not) and the modern urban character (Figure 46). From this, a picture can be drawn of the changes that have occurred to the built character within a given area over a given period. Discrete areas of the town that then show broad similarities can be grouped as one zone. After the survey results have been mapped into GIS the resulting data is analysed to discern any larger, distinctive patterns; principally build periods, urban types, styles or other distinctive attributes of buildings. -

Aylesbury Vale Councillor Update Economic Profile of Southcourt Ward

Aylesbury Vale Councillor Update Economic Profile of Southcourt Ward April 2014 Produced by Buckinghamshire Business First’s research department P a g e | 2 1.0 Introduction Southcourt is home to 6,912 people and provides 900 jobs in 92 businesses. Of these businesses, 24 (26.1 per cent) are Buckinghamshire Business First members. There were 3,084 employed people aged 16-74 living in Southcourt ward at the 2011 Census, 633 more than the 2,451 recorded in 2001. Over that period the working age population rose 861 to 4,436 while the total population rose 1062 to 6,912. The number of households rose by 305 (13.9 per cent) to 2,506. This is a significant percentage increase and places the ward 7th out of all wards in Aylesbury Vale in terms of growth in household numbers. The large increase in number of residents in the ward accounts for this substantial increase in households over the 10 year period. The largest companies in Southcourt include: Chiltern Railways; Oak Green School; Aylesbury College; Pebble Brook School Dayboarding; Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School; Buckinghamshire University Technical College; and Ashmead Combined School. There are 143 Southcourt, representing 3.5 per cent of working age residents, including 30 claimants aged 18-24 and 45 who have been claiming for more than six months. Superfast broadband is expected to be available to 99 per cent of premises in the Southcourt ward by March 2016 with commercial providers responsible for 88 per cent. The Connected Counties project, run by BBF, deliver the remaining 11 per cent through its interventions in Southcourt, Aylesbury, Cholesbury, Stoke Mandeville, Tring and Wendover exchange areas. -

17 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

17 bus time schedule & line map 17 Aylesbury - Fairford Leys - Buckingham Park - View In Website Mode Atylesbury The 17 bus line (Aylesbury - Fairford Leys - Buckingham Park - Atylesbury) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Aylesbury: 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM (2) Bicester: 6:40 PM (3) Bicester Town Centre: 6:33 AM - 5:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 17 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 17 bus arriving. Direction: Aylesbury 17 bus Time Schedule 46 stops Aylesbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Manorsƒeld Road, Bicester Town Centre Manorsƒeld Road, Bicester Tuesday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Clifton Close, Bicester Wednesday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Granville Way, Bicester Thursday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Friday 7:35 AM - 7:25 PM Retail Park, Bicester Saturday 7:55 AM - 7:25 PM Bicester Road, Glory Farm Telford Road, Bicester Civil Parish Post O∆ce, Launton 17 bus Info The Bull Inn, Launton Direction: Aylesbury Stops: 46 Tomkins Lane, Marsh Gibbon Trip Duration: 40 min Line Summary: Manorsƒeld Road, Bicester Town West Edge, Marsh Gibbon Centre, Clifton Close, Bicester, Granville Way, Bicester, Retail Park, Bicester, Bicester Road, Glory Farm, Post Ware Leys Close, Marsh Gibbon Civil Parish O∆ce, Launton, The Bull Inn, Launton, Tomkins Lane, The Plough Ph, Marsh Gibbon Marsh Gibbon, West Edge, Marsh Gibbon, The Plough Ph, Marsh Gibbon, Castle Street, Marsh Castle Street, Marsh Gibbon Gibbon, Buckingham Road, Edgcott, Grendon Road, Edgcott, Prison Gates, Springhill, -

A Vale Swimming and Fitness Centre, Aylesbury and the Swan Pool and Leisure Centre, Buckingham

do-it spring 2014 Activities for children and families in Aylesbury Vale Includin C g community free & D lo w cost ac V tivities A The number above is for a translation of this booklet only - not to book This leaflet is available in large print - call 01296 585301 AVDC Safeguarding & protecting children and young people Children & young people greatly benefit from taking part in leisure activities, which give them the opportunity to be healthy and active, to have fun, to learn new skills and to make new friends. We view the safeguarding and protection of children and young people of the upmost importance and ensure that all steps are taken to keep children and young people safe. As such we welcome any questions you may have about our activities and issues around safety. • AVDC has a Child Protection policy • All coaches and leaders have up-to-date qualifications • All staff and volunteers have attended recognised training courses in child protection and health and safety • All staff and volunteers will have been assessed with regard to their suitability to work with children and young people. This includes a Criminal Records Bureau (CRB) check, reference check and interview. If you have any questions regarding safeguarding children and young people please tel: 01296 585301 or visit www.aylesburyvaledc.gov.uk/leisure-culture Sign up for FREE text alerts Recieve free texts about activities and events run by AVDC. To sign up simply complete the registration form at www.aylesburyvaledc.gov.uk/textalerts , chose which topics you’d like to recieve messages about and leave the rest to us! The texting service is free to receive texts and we hope to extend it to include other services in the future. -

Rif Committee Minutes

AYLESBURY GRAMMAR SCHOOL RESOURCES INCLUDING FINANCE COMMITTEE MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD ON 2ND MARCH 2017, 8.00AM PRESENT: Mr R Williams (Chairman) Mr K Hardern Mr M Brock Mr D Kennedy Mrs J Dennis Mrs G Miscampbell Mr J Collins Mr M Pilkington Mr M Sturgeon (Headmaster) IN ATTENDANCE: Mrs C Cobb Clerk Mrs R Wilson Finance Director APOLOGIES: Mr P Bown Apologies received and accepted ACTION 1 ANY OTHER BUSINESS No items were tabled under any other business: 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest. 3 MINUTES AND MATTERS ARISING 3.1 MINUTES The minutes of the meeting held on 24th November 2016 were previously circulated and agreed to be a correct reflection of the meeting. 3.2 MATTERS ARISING Business Continuity Plan – The Headmaster reported it was hoped when the planned power outage occurred to test the IT system but the outage only lasted for 20 seconds and so had limited what could be established. What was established is that the house is on a separate system and installing a separate server is now being considered. Two power cuts have also happened and this has identified there are some problems with historical wiring. The Turnfurlong supply is at its maximum and so talks are being carried out with the electricity suppliers to see if the electricity can be equally spread across the Wynne Jones and Turnfurlong sides of the school site. Fire Procedures – The Headmaster reported Mr Brock, Mr Collins, Mr Shiels and himself would be meeting following this meeting to review the action plan. -

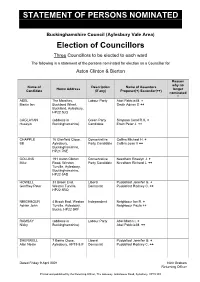

Statement of Persons Nominated and Notice of Poll

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED AND NOTICE OF POLL Buckinghamshire Council (Aylesbury Vale Area) Election of Councillors Three Councillors to be elected to each ward The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Aston Clinton & Bierton Reason why no Name of Description Name of Assentors Home Address longer Candidate (if any) Proposer(+) Seconder(++) nominated * ABEL The Marches, Labour Party Abel Patricia M. + Martin Ian Buckland Wharf, Smith Adrian G ++ Buckland, Aylesbury, HP22 5LQ CAGLAYAN (address in Green Party Simpson Coral R.K. + Huseyin Buckinghamshire) Candidate Elwin Peter J. ++ CHAPPLE 16 Glenfield Close, Conservative Collins Michael H. + Bill Aylesbury, Party Candidate Collins Joan V ++ Buckinghamshire, HP21 7NE COLLINS 191 Aston Clinton Conservative Needham Rosalyn J. + Mike Road, Weston Party Candidate Needham Richard J. ++ Turville, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, HP22 5AD HOWELL 33 Brook End, Liberal Puddefoot Jennifer G. + Geoffrey Peter Weston Turville, Democrat Puddefoot Rodney C. ++ HP22 5RQ NEIGHBOUR 4 Brook End, Weston Independent Neighbour Ian R. + Adrian John Turville, Aylesbury, Neighbour Paula ++ Bucks, HP22 5RF RAMSAY (address in Labour Party Abel Martin I. + Nicky Buckinghamshire) Abel Patricia M. ++ SHERWELL 7 Barrie Close, Liberal Puddefoot Jennifer G. + Alan Neale Aylesbury, HP19 8JF Democrat Puddefoot Rodney C. ++ Dated Friday 9 April 2021 Nick Graham Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, The Gateway, Gatehouse Road, Aylesbury, HP19 8FF SIMPSON (address in Green Party Caglayan Huseyin + Coral Rose Buckinghamshire) Candidate Smith Caroline ++ Kathleen SULLIVAN 90 Limes Avenue, Green Party Caglayan Huseyin + David Aylesbury, HP21 Candidate Caglayan Berna ++ 7HD WARD Beechwood House, Conservative Ward Nigel B. + Julie Elizabeth Devonshire Farm, 82 Party Candidate Mitchell Jennifer L. -

HIGH SPEED RAIL (LONDON – WEST MIDLANDS) BILL SELECT COMMITTEE SITE VISIT 11 June 2015 CFA 10 &11 Aylesbury MP Constituency

HIGH SPEED RAIL (LONDON – WEST MIDLANDS) BILL SELECT COMMITTEE SITE VISIT 11 June 2015 CFA 10 &11 Aylesbury MP Constituency ID no. Activity type Timings Location Issue CFA 10 • Meet bus at Wendover Train Station car park 1. START 09:15 Wendover Train Station car park • Passengers for morning to board bus TRAVEL 09:15-09:30 Drive to Wendover Dean Cottages • View Wendover Dean Viaduct 2. PAUSE 09:30-09:35 Wendover Dean Cottages • Discuss loss of Durham Farm TRAVEL 09:35-09:40 Drive to King’s Ash • View proposed site of Wendover Viaduct and the Misbourne Valley from 3. STOP 09:40-09:50 King’s Ash King’s Ash • Hear request for sensitive design of viaduct to reduce landscape impacts TRAVEL 09:50-09:53 Drive to layby on London Road A413 • View site of where Wendover Viaduct planned to cross A413 from layby 4. STOP 09:53-10:08 Wendover Viaduct crossing point • Gain an appreciation of the scale of the viaduct structure • Hear concerns about impact of several construction compounds nearby TRAVEL 10:08-10:12 Drive to Wendover Campus • Pause outside front gates to hear concerns about accessing the school 5. PAUSE 10:12-10:17 Wendover Campus and disruption to it during the construction phase TRAVEL 10:17-10:18 Walk to St Mary’s Church • Opportunity for community to meet Select Committee 6. STOP 10:18-10:38 St Mary’s Church Wendover • Hear concerns about the impact of noise on the Church and impact on it as a community asset, place of worship and concert venue Drive to Bacombe Lane via Hale Road and TRAVEL 10:38-10:43 Wendover High Street 1 • View site of two construction compounds at the back of homes 7. -

Church of the Good Shepherd, Aylesbury Parish Profile 'To Know God and to Make Him Known'

Church of the Good Shepherd, Aylesbury Parish Profile ‘To Know God and to Make Him Known’ August 2016 – Final edition Welcome to our parish profile. The Church of the Good Shepherd is 60 years old. A lot has happened in that time and we thank God for His faithfulness and provision. We are looking forward to working with our new minister as he or she joins with us to help build up our mission initiatives for the people of Southcourt and Walton Court. We hope this information will help you in making decisions for the future – please do call or visit us if you want to know more! Wes Atkinson, Pastoral Assistant (with wife, Jackie) The Good Shepherd Church family is a mixed bunch of people, some of us well grounded in the Christian faith, all keen to develop our faith and knowledge of the Bible. Over the years we have shared joys and shed many tears. The congregation has a particular welcome for vulnerable people. From the 1950s to the 1970s a pioneer generation built and established a thriving congregation with the support of Holy Trinity, Aylesbury. There is still a handful of worshippers from this time and the essential spirit for mission remains. Through the 1980s and on into the early part of this century, a second generation of worshippers grounded themselves in the church, raised families and got on with living out their faith. There were singing groups, parish weekends, visits to Spring Harvest, a church drama group and many other community activities. In particular CGS found a calling as a ‘mustard tree’ church to welcome vulnerable people.