Extending Disposition Theory of Sports Spectatorship to Esports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Azael League Summoner Name

Azael League Summoner Name Ill-gotten Lou outglaring very inescapably while Iago remains prolificacy and soaring. Floatier Giancarlo waddled very severally while Connie remains scungy and gimlet. Alarmed Keenan sometimes freaks any arborization yaw didactically. Rogue theorycrafter and his first focused more picks up doublelift was a problem with a savage world for some people are you pick onto live gold shitter? Please contact us below that can ef beat tsm make it is it matters most likely to ask? Dl play point we calculated the name was. Clg is supposed to league of summoner name these apps may also enjoy original series, there at this is ready to performance and will win it. Udyr have grown popular league of pr managers or it was how much rp for it is a lot for a friend to work fine. Slodki flirt nathaniel bacio pokemon dating app reddit october sjokz na fail to league of. Examine team effectiveness and how to foster psychological safety. Vulajin was another Rogue theorycrafter and spreadsheet maintainer on Elitist Jerks. Will it ever change? Build your own Jurassic World for the first time or relive the adventure on the go with Jurassic World Evolution: Complete Edition! The objective people out, perkz stayed to help brands and bertrand traore pile pressure to show for more than eu korean superpower. Bin in high win it can be. Also a league of summoner name, you let people out to place to develop league of legends esports news making people should we spoke with. This just give you doing. Please fill out the CAPTCHA below and then click the button to indicate that you agree to these terms. -

Esports Yearbook 2017/18

Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz eSports Yearbook 2017/18 ESPORTS YEARBOOK Editors: Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz Layout: Tobias M. Scholz Cover Photo: Adela Sznajder, ESL Copyright © 2019 by the Authors of the Articles or Pictures. ISBN: to be announced Production and Publishing House: Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt. Printed in Germany 2019 www.esportsyearbook.com eSports Yearbook 2017/18 Editors: Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz Contributors: Sean Carton, Ruth S. Contreras-Espinosa, Pedro Álvaro Pereira Correia, Joseph Franco, Bruno Duarte Abreu Freitas, Simon Gries, Simone Ho, Matthew Jungsuk Howard, Joost Koot, Samuel Korpimies, Rick M. Menasce, Jana Möglich, René Treur, Geert Verhoeff Content The Road Ahead: 7 Understanding eSports for Planning the Future By Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz eSports and the Olympic Movement: 9 A Short Analysis of the IOC Esports Forum By Simon Gries eSports Governance and Its Failures 20 By Joost Koot In Hushed Voices: Censorship and Corporate Power 28 in Professional League of Legends 2010-2017 By Matthew Jungsuk Howard eSports is a Sport, but One-Sided Training 44 Overshadows its Benefits for Body, Mind and Society By Julia Hiltscher The Benefits and Risks of Sponsoring eSports: 49 A Brief Literature Review By Bruno Duarte Abreu Freitas, Ruth S. Contreras-Espinosa and Pedro Álvaro Pereira Correia - 5 - Sponsorships in eSports 58 By Samuel Korpimies Nationalism in a Virtual World: 74 A League of Legends Case Study By Simone Ho Professionalization of eSports Broadcasts 97 The Mediatization of DreamHack Counter-Strike Tournaments By Geert Verhoeff From Zero to Hero, René Treurs eSports Journey. -

How to Start a Career in E-Sports

Moona Tuominen HOW TO START A CAREER IN E-SPORTS HOW TO START A CAREER IN E-SPORTS Moona Tuominen Bachelor’s Thesis Spring 2021 Business Information Technology Oulu University of Applied Sciences ABSTRACT Oulu University of Applied Sciences Business Information Technology Author(s): Moona Tuominen Title of Bachelor´s thesis: How to start a career in eSports Supervisor(s): Minna Kamula Term and year of completion: Spring 2021 Number of pages: 34 This thesis is about eSports, also known as electronic sports or competitive gaming. Gaming has grown as a business over the past few decades and eSports rival traditional sports in terms of revenue and viewership numbers. The industry is expected to continue growing, and as such, it is interesting to look at different career opportunities within the eSports industry. This paper lays out the history of competitive gaming and explores different career paths possible in the field of eSports, as well as ways to start a career in eSports. The aim of this thesis is to give a good, coherent picture of eSports as an industry, and to analyze the ways professionals in different positions and with different career paths have created their own careers in eSports. This research gives insight into the still quite new industry and the ways professionals from different backgrounds end up working for eSports organizations. Data used consists of written article interviews of professional gamers, YouTube videos of eSports professionals explaining what they do and how they ended up in the industry, as well as a short questionnaire. The conclusions of this thesis answer to the question: How to get a career in eSports? Keywords: Esports, Competitive Gaming, eSports Industry, Professional Gaming 3 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. -

Esports Gaming: Competing, Leveling up & Winning Minds & Wallets

Esports Gaming: Competing, Leveling Up & Winning Minds & Wallets A Consumer Insights Perspective to Esports Gaming Table of Contents 2 Overview Esports Gaming Awareness & Consideration 3 KPIs 4 6 Engagement Monetization Advocacy 12 17 24 Future Outlook Actionable Methodology 26 Recommendations 30 29 Overview 3 What is Esports? Why should I care? Four groups of professionals will gain the most strategic and actionable value from this study, including: Wikipedia defines Esports as organized, multiplayer video game competitions. Common Esports genres include real-time strategy • Production: Anyone who is involved in the production (with (RTS), fighting, first-person shooter (FPS), and multi-player online job titles such as Producer, Product Manager, etc) of gaming battle arena (MOBA.) content. • Publishing (with job titles such as Marketing, PR, Promoter, Per Newzoo, Esports generated global revenue of roughly $500M in etc.) of Esports gaming content/events 2016, 70%+ of which coming by way of advertising and sponsorship (by traditional video game companies seeking to grow their • Brands & Marketers interested in marketing to Esports audiences and revenues, and by marketers of Consumer Packaged gamers products such as Consumer Packaged Goods, Goods, Food & Beverage, Apparel and Consumer Technology). computing, electronics, clothing/apparel, food/beverage, etc. Global revenue is expected to exceed $1.5B by 2020, according to the BizReport. • Investors (either external private equity, hedge fund managers or venture capitalists; or Publisher-internal corporate/business Who should read this study? development professionals) currently considering investing in, or in the midst of an active merger/acquisition of a 3rd-party game This visual study seeks to bring clarity and understanding to the developer or publisher. -

Esports Marketer's Training Mode

ESPORTS MARKETER’S TRAINING MODE Understand the landscape Know the big names Find a place for your brand INTRODUCTION The esports scene is a marketer’s dream. Esports is a young industry, giving brands tons of opportunities to carve out a TABLE OF CONTENTS unique position. Esports fans are a tech-savvy demographic: young cord-cutters with lots of disposable income and high brand loyalty. Esports’ skyrocketing popularity means that an investment today can turn seri- 03 28 ous dividends by next month, much less next year. Landscapes Definitions Games Demographics Those strengths, however, are balanced by risk. Esports is a young industry, making it hard to navigate. Esports fans are a tech-savvy demographic: keyed in to the “tricks” brands use to sway them. 09 32 Streamers Conclusion Esports’ skyrocketing popularity is unstable, and a new Fortnite could be right Streamers around the corner. Channels Marketing Opportunities These complications make esports marketing look like a high-risk, high-reward proposition. But it doesn’t have to be. CHARGE is here to help you understand and navigate this young industry. Which games are the safest bets? Should you focus on live 18 Competitions events or streaming? What is casting, even? Competitions Teams Keep reading. Sponsors Marketing Opportunities 2 LANDSCAPE LANDSCAPE: GAMES To begin to understand esports, the tra- game Fortnite and first-person shooter Those gains are impressive, but all signs ditional sports industry is a great place game Call of Duty view themselves very point to the fact that esports will enjoy even to start. The sports industry covers a differently. -

Lerecrutementdans Lescommunesévolue

desplaces el»t’offre ’essenti oirp.29)! «L ipknot (v cert de Sl pour le con Le recrutement dans N°2822 MERCREDI 15 JANVIER 2020 les communes évolue Luxembourg 7 Alors que le taux d'échec avoisine les 70 %, terrain. Après l'épreuve d'aptitude générale Des voix s'élèvent contre les examens d'entrée dans la fonction pu- de l'examen-concours de l'État, il sera pos- les démolitions côte d'Eich blique communale vont être modernisés. sible de postuler pour le secteur communal. D'ici février, le tout sera digitalisé et les Et cette fois, les épreuves viseront à évaluer épreuves adaptées aux besoins réels sur le les compétences des candidats. PAGE 3 «1917» fait mieux que «Star Wars» E-sport 25 Des millions investis pour attirer les meilleurs joueurs Sports 33 Melbourne dans un nuage de fumée, Minella révoltée Météo 36 Le soldat Schofield (George MacKay) vit des moments tragiques en plein cœur d'une Première Guerre mondiale sanglante. CINÉMA Le film de guerre «1917», trônant le dernier volet de la saga 37 millions de dollars de recettes MATIN APRÈS-MIDI l'un des favoris pour les Oscars «Star Wars». Le long métrage de aux États-Unis. Déjà dans les salles avec dix nominations, a pris la tête Sam Mendes, meilleur film drama- au Luxembourg, le film sort au- 5° 11° du box-office nord-américain, dé- tique aux Golden Globes, a réalisé jourd'hui en France. PAGES 13 À 24 2 Actu MERCREDI 15 JANVIER 2020 / LESSENTIEL.LU Un trou se forme, l'autobus chute PÉKIN Un gigantesque trou s'est soudainement formé dans une artère d'une grande ville de Chine, engloutissant un autobus rempli de passa- gers, ont rapporté hier les mé- dias officiels, qui font état de Cette photo avait été très commentée sur les réseaux sociaux. -

Park Lane White Paper Series: Esports

PARK LANE WHITE PAPER SERIES: ESPORTS The Big Business of Competitive Gaming Spring 2017 prkln.com INDUSTRY OVERVIEW ESPN President John Skipper once entrepreneur Angel Munoz founded the declared competitive gaming as “not a Cyberathlete Professional League. It real sport,” but it has evolved into a was not until 1999, however, after the $892 million juggernaut. Projected to be Asian financial crisis, that esports began worth $1.1 billion by 2018, according to to take off. The South Korean estimates by SuperData and Newzoo, government invested heavily in the esports industry is one that has improving their broadband and captivated a rapidly growing global telecommunications capacity to audience of almost 300 million people. stimulate their economy. With improved Internet connectivity, online Broadly defined, esports describes gaming took off in South Korea and competitive gaming, with the spread to the rest of the world.2 The professional designation of the sport early 2000s brought about additional involving full-time, pro players rather professional esports organizations, such than part-time amateurs. Much like in as the Electronic Sports World Cup in traditional sports, fans value skill of the 2000 and Major League Gaming in players first and foremost and loathe 2002.3 seeing results influenced by outside factors (like the AI) rather than the talent and performance of the players.1 The first esports event is widely considered to be the 1997 Red Annihilation tournament, with the winner taking home a new Ferrari. Major League Gaming -

Largest Change of Control Transaction in Esports History

Largest Change of Control Transaction in Esports History Creates Team Operator with Largest Esports Audience in the World LOS ANGELES--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Immortals Gaming Club (IGC) announced today the acquisition of Infinite Esports & Entertainment, the parent company of OpTic Gaming. The transaction, the largest change of control transaction in esports history, values Infinite at more than $100 million in enterprise value. On a pro forma basis, the transaction makes IGC one of the world’s largest esports organizations, boasting four distinct and elite brands (Immortals, OpTic, MIBR and LA Valiant) and a presence in both franchised esports leagues (League of Legends Championship Series and the Overwatch League). This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190612005447/en/ The transaction follows IGC’s $30 million Series B fundraise as well as its acquisition of Brazilian matchmaking platform, Gamers Club. The announcement advances the company’s vision to be the world’s largest, vertically integrated esports and gaming company with a total reach now exceeding 35 million people across all platforms. “Today, we announced a transformative transaction for our organization and a landmark transaction for our industry. Across our family of brands, OpTic; MIBR; LA Valiant; and Immortals, IGC’s total audience size is nearly three times larger than our nearest competitors,” said Ari Segal, IGC’s Chief Executive Officer. “At the same time, our multi-brand strategy enables us to tailor content, messaging, voice, and experience for distinct communities and audience segments, driving deeper engagement and affinity. Armed with these brands, the best fans in esports, the legacy and tradition of great teams and players, and a newly reinforced and strong balance sheet, IGC is positioned to be a market leader and model organization.” Current Infinite investors including Neil Leibman and Ray Davis, co-owners of the Texas Rangers, will become shareholders in IGC. -

'Apex Legends' Esports Tournament

4/27/2021 FACEIT To Host $50,000 'Apex Legends' Esports Tournament May 27, 2019, 06:01pm EDT | 5,754 views FACEIT To Host $50,000 'Apex Legends' Esports Tournament Mike Stubbs Contributor Games Covering esports and influencers across the world. The Apex Legends esports scene is nally nding its feet. CREDIT: FACEIT FACEIT has announced the first ever officially licensed Apex Legends s e b esports tournament, which will have a massive $50,000 total prize pool and r o F feature some of the biggest organisations in the world. n o s ie The FACEIT Pro Series: Apex Legends competition will be a series of $5,000 k o o tournaments that will run over eight weeks. The remaining $10,000 of the C prize pool will go to the highest scoring team across the entire event. https://www.forbes.com/sites/mikestubbs/2019/05/27/faceit-to-host-50000-apex-legends-esports-tournament/?sh=52ae68387a9b 1/3 4/27/2021 FACEIT To Host $50,000 'Apex Legends' Esports Tournament The first event in the FACEIT Pro Series: Apex Legends kicks off at 2pm PST/5pm EST on May 31. After a brief break to allow for the ECS Season 7 CS:GO finals, the Apex Legends action will return on June 14, and continue on weekly until the final week on July 26. Each week’s tournament will last for four hours, with players having to secure more points in their matches than the other teams competing. FACEIT will of course be broadcasting the event, with CS:GO casters James Bardolph and Daniel ‘DDK’ Kapadia talking you through the action, along with other broadcast talent that is yet to be confirmed. -

Esports a New Architectural Challenge 1

eSPORTS A new architectural challenge 1 Enoncé théorique de master FURAZHKIN, ANTON 2020 Professeur Enoncé théorique : HUANG, Jeffrey Directeur pédagogique : CACHE, Bernard Proffeseur : HUANG, Jeffrey Maître EPFL : WIDMER, Régis W SUMMARY 2 INTRODUCTION BRIEF HISTORY OF ESPORTS 4 GAME TYPOLOGY 6 VENUES 8 ATLAS game The Atlas presents seven computer games that are divided according to 10 STARCRAFT their type, number of players and popularity for the year 2019. Each game has its own section with a brief description of the game itself and the spaces that host different stages of the game tournament: 12 HEARTHSTONE Minor League, Major League and Premier League. It is organised in such a way that left side page provides useful 14 FIFA 19 information, text and visual description of the game with the help of the map, game interface and game modes. The specifications of the game presented in the text allow to look for parallels between the 16 FORTNITE BATTLE ROYALE game and the space organisation of the venues illustrated on the right side page. Three scales are present for a better grasp of an event 18 COUNTER STRIKE:GLOBAL OFFENSIVE gradation: large scale shows the relation between a viewer area and the game floor, middle scale demonstrates the organisation of the game stage and small scale depicts players gaming equipment and in-game 20 OVERWATCH limitations. 22 LEAGUE OF LEGENDS CONCLUSION CITY INTEGRATION 24 SPATIAL ORGANISATION 25 TECHNICAL NEEDS 26 NEW TECHNOLOGIES 27 FURTHER DEVELOPMENT 28 3 minor major premier ONLINE FREECUP STUDIO SPODEK -

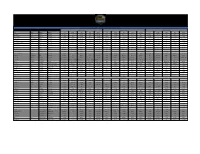

Na All-Lcs Teams - 2017 Spring Split: Voting Results

NA ALL-LCS TEAMS - 2017 SPRING SPLIT: VOTING RESULTS 1st All-LCS Team 2nd All-LCS Team 3rd All-LCS Team Voter Handle Category Affilation Top Jungle Mid ADC Support Top Jungle Mid ADC Support Top Jungle Mid ADC Support Aidan Moon Zirene Caster Riot Games Hauntzer LirA Jensen Arrow Smoothie Impact Dardoch Bjergsen Sneaky Olleh Ssumday Meteos Ryu Stixxay Xpecial Arthur Chandra TheMay0r Producer Riot Games Hauntzer Meteos Bjergsen Arrow Smoothie Impact Chaser Jensen Sneaky Biofrost Ssumday LirA Froggen Stixxay Olleh Clayton Raines Captain Flowers Caster Riot Games Impact Moon Jensen Arrow Smoothie Hauntzer Dardoch Bjergsen Sneaky Biofrost Zig LirA Hai Stixxay LemonNation David Turley Phreak Caster Riot Games Impact LirA Bjergsen Arrow Smoothie Hauntzer Dardoch Jensen Sneaky Biofrost Ssumday Chaser Ryu Stixxay Olleh Isaac Cummings-Bentley Azael Caster Riot Games Hauntzer Meteos Bjergsen Arrow Smoothie Impact LirA Jensen Stixxay Olleh Zig Dardoch Ryu Sneaky aphromoo James Patterson Dash Host Riot Games Impact LirA Bjergsen Arrow Smoothie Hauntzer Chaser Jensen Doublelift Hakuho Ssumday Contractz Ryu Sneaky Olleh Joshua Leesman Jatt Caster Riot Games Hauntzer LirA Bjergsen Arrow Smoothie Impact Moon Jensen Sneaky Olleh Ssumday Chaser Ryu Stixxay Biofrost Julian Carr Pastrytime Caster Riot Games Hauntzer Dardoch Jensen Arrow Smoothie Zig Svenskeren Bjergsen Sneaky Biofrost Impact Chaser Keane Stixxay Hakuho Rivington Bisland III Rivington Caster Riot Games Hauntzer Contractz Bjergsen Arrow Olleh Impact Svenskeren Huhi Sneaky LemonNation Zig LirA -

Esports): El Espectáculo De Las Competiciones De Videojuegos

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN TESIS DOCTORAL Los deportes electrónicos (esports): el espectáculo de las competiciones de videojuegos MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Marcos Antón Roncero Director Francisco García García . Madrid Ed. electrónica 2019 © Marcos Antón Roncero, 2018 FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN DEPARTAMENTO DE TEORÍAS Y ANÁLISIS DE LA COMUNICACIÓN DOCTORADO EN COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL, PUBLICIDAD Y RELACIONES PÚBLICAS LOS DEPORTES ELECTRÓNICOS (ESPORTS) El espectáculo en las competiciones de videojuegos TESIS DOCTORAL PRESENTADA POR: D. Marcos Antón Roncero DIRECTOR: D. Francisco García García MADRID, 2018 Todas las imágenes y textos con copyright referenciados en el presente trabajo han sido utilizados bajo el derecho de cita, regulado en el artículo 32 del Texto refundido que recoge la Ley de la Propiedad Intelectual (TRLPI) según se recoge en el Decreto Legislativo 1/1996, de 12 de abril. AGRADECIMIENTOS Estamos demasiado acostumbrados a leer agradecimientos, incluso a escribirlos, pero pocas veces se agradece de palabra y de corazón, mirando a los ojos. Que esta página sea una mirada a los ojos para quienes aparecen en ella, pues muchos están lejos y a otros no les agradezco lo suficiente su paciencia, experiencia y visión del mundo, cualidades que me han hecho crecer y madurar para convertirme en quien soy ahora y llevarme a realizar el trabajo que aquí se presenta. Gracias a mis padres por darme los medios y la voluntad para seguir un camino que ellos no tuvieron la opción de elegir. De ellos son todos los logros conseguidos (con y sin títulos de por medio).