SESSION 12 Neo-Impressionism and Post-Impressionism (Monday 4Th November & Tuesday 3Rd December)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern

Lauren Jimerson exhibition review of Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Citation: Lauren Jimerson, exhibition review of “Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern ,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw. 2020.19.1.14. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Jimerson: Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Grand Palais, Paris October 9, 2019–January 27, 2020 Catalogue: Stéphane Guégan ed., Toulouse-Lautrec: Résolument moderne. Paris: Musée d’Orsay, RMN–Grand Palais, 2019. 352 pp.; 350 color illus.; chronology; exhibition checklist; bibliography; index. $48.45 (hardcover) ISBN: 978–2711874033 “Faire vrai et non pas idéal,” wrote the French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864– 1901) in a letter to his friend Étienne Devismes in 1881. [1] In reaction to the traditional establishment, constituted especially by the École des Beaux-Arts, the Paris Salon, and the styles and techniques they promulgated, Toulouse-Lautrec cultivated his own approach to painting, while also pioneering new methods in lithography and the art of the poster. He explored popular, even vulgar subject matter, while collaborating with vanguard artists, writers, and stars of Bohemian Paris. Despite his artistic innovations, he remains an enigmatic and somewhat liminal figure in the history of French modern art. -

The Centenary of Independence Two Young Peasant Women

The Centenary of Independence by Henri Rousseau Painted in 1892, this depicts the celebration of the French independence of 1792. There are peasants dancing the farandole under a liberty tree. Serious and dignified republican leaders look on at the happy people of France. The bright colors and solid figures are allegorical of the radiant and strong state of France under its good government. Two Young Peasant Women by Camille Pissaro This was painted in 1891. The artist had a desire to “educate the people” by depicting scenes of people working on farms and in rural settings. He made an effort to be realist rather than idealistic. He wanted to depict people as they really were not in order to make allegorical statements or send political messages. Exotic Landscape by Henri Rousseau This was painted in 1908 and is part of a series of jungle scenes by this artist. He purposely painted in a naive or primitive style. Though the painting looks simplistic the lay- ers of paint are built up layer by meticulous layer to give the depth of color and vibrancy that the artist desired. He didn’t even begin painting until he was in his forties, but by the age of 49 he was able to quit his regular job and paint full time. He was self taught. When Will You Marry? by Paul Gauguin The artist moved to Tahiti from his native France, looking for a simpler life. He was disappointed to find Tahiti colonized and most of the traditional lifestyle gone. His most famous paintings are all of Tahitian scenes. -

Paul Gauguin

Sarah Kapp Art History and Visual Studies Major (honours) Business Minor De-Mythicizing the Artist: Presented March 6, 2019 This research was supported by the Jamie Cassels Undergraduate Research Award University of Victoria Supervised by Dr. Catherine Harding How Gauguin Responded to the Art Market Assistance from Dr. Melissa Berry Political Conditions Introduction Imperialism and Primitivism in the Late-Nineteenth Century Like celebrities, famous artists face rumours and myths Gauguin’s stylistic innovations were just one component of his self-promotional endeavor that overwhelm their public reception. Vincent van Gogh that appeared in the Volpini Suite. It was his engagement with ‘primitive’ subject- has become inextricably linked to the tale of the tortured matter—which included depictions of local peasant and folk culture—that served as a soul who sliced off his ear; Pablo Picasso to the tale fashionable and marketable technique (Perry 6). In the 1889 suite, Gauguin depicted of the womanizing innovative artist; and Salvador Dalí people in their daily surroundings, including: Breton peasant women chatting, Martinican as the eccentric artist who did too many drugs. This women carrying baskets of fruit, and women from Arles out walking (Juszczak 119). research dismantles the myth of Paul Gauguin (1848- After his creation of the Volpini Suite, Gauguin’s use of ‘primitive’ subjects intensified, 1903), who, in the late-twentieth century, became ultimately becoming a defining feature of his artistic practice. Gauguin’s work in the the target of feminist and post-colonialist theorists, Volpini Show correlated to contemporary ideas about the ‘primitive’. The Exposition who criticized him for sexualized depictions of young Universelle juxtaposed the newly built Eiffel Tower and the Gallery of Machines with women, as well as ‘plagiarizing’ and ‘pillaging’ the art ethnographic exhibits from around the world (Chu 439). -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

Art-Related Archival Materials in the Chicago Area

ART-RELATED ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN THE CHICAGO AREA Betty Blum Archives of American Art American Art-Portrait Gallery Building Smithsonian Institution 8th and G Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20560 1991 TRUSTEES Chairman Emeritus Richard A. Manoogian Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin Mrs. Richard Roob President Mrs. John N. Rosekrans, Jr. Richard J. Schwartz Alan E. Schwartz A. Alfred Taubman Vice-Presidents John Wilmerding Mrs. Keith S. Wellin R. Frederick Woolworth Mrs. Robert F. Shapiro Max N. Berry HONORARY TRUSTEES Dr. Irving R. Burton Treasurer Howard W. Lipman Mrs. Abbott K. Schlain Russell Lynes Mrs. William L. Richards Secretary to the Board Mrs. Dana M. Raymond FOUNDING TRUSTEES Lawrence A. Fleischman honorary Officers Edgar P. Richardson (deceased) Mrs. Francis de Marneffe Mrs. Edsel B. Ford (deceased) Miss Julienne M. Michel EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Members Robert McCormick Adams Tom L. Freudenheim Charles Blitzer Marc J. Pachter Eli Broad Gerald E. Buck ARCHIVES STAFF Ms. Gabriella de Ferrari Gilbert S. Edelson Richard J. Wattenmaker, Director Mrs. Ahmet M. Ertegun Susan Hamilton, Deputy Director Mrs. Arthur A. Feder James B. Byers, Assistant Director for Miles Q. Fiterman Archival Programs Mrs. Daniel Fraad Elizabeth S. Kirwin, Southeast Regional Mrs. Eugenio Garza Laguera Collector Hugh Halff, Jr. Arthur J. Breton, Curator of Manuscripts John K. Howat Judith E. Throm, Reference Archivist Dr. Helen Jessup Robert F. Brown, New England Regional Mrs. Dwight M. Kendall Center Gilbert H. Kinney Judith A. Gustafson, Midwest -

Mnittv of Fmt ^Rt (M

PAULGAUGUIN AS IMPRESSIONIST PAINTER - A CRITICAL STUDY DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRIMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Mnittv of fmt ^rt (M. F. A.) BT MS. SAB1YA K4iATQQTI Under the supervision of 0^v\o-vO^V\CM ' r^^'JfJCA'-I ^ M.JtfzVl Dr. (Mrs.) SIRTAJ RIZVl Co-Supervisor PARTMENT OF FINE ART IGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 DS2890 ^^ -2-S^ 0 % ^eAtcMed to ^ff ^urents CHAIRMAN ALiGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS ALIGARH—202 002 (U.P.). INDIA Dated. TO WHOM IT BIAY CONCERN This is to certify that Miss Sabiya Khatoon of Master of Fine Arts (M.F.A.) has completed her dissertation entitled "PAOL GAUGUIN AS IMPRESSIONIST PAINTER - A CRITICAL STUDY", under the supervision of Prof. Ashfaq M. Rizvi and Co-Supervision Dr. (Mrs.) Sirtaj Rizvi, Reader, Department of Fine Arts. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the work is based on the investigations made, data collected and analysed by her and it has not been submitted in any other University or Institution for any Degree. 15th MAY, 1997 ( B4RS. SEEMA JAVED ) ALIGARH CHAIRMAN PHONES—OFF. : 400920,400921,400937 Extn. 368 RES. : (0571) 402399 TELEX : 564—230 AMU IN FAX ; 91—0571—400528 CONTENTS PAGE ND. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 1. INTRODUCTION 1-19 2. LIFE SKETCH OF PAUL 20-27 GAUGUIN 3. WORK AND STYLE 28-40 4. INFLUENCE OF PAUL 41-57 GAUGUIN OWN MY WORK 5. CONCLUSION ss-eo INDEX OF PHOTOGRAPHS BIBLIOGRAPHY ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I immensely obliged to my Supervisor Prof. Ashfaq Rizvi whose able guidance and esteemed patronage the dissertation would be given final finishing. -

Famous Impressionist Artists Chart

Impressionist Artist 1 of the Month Name: Nationality: Date Born:________Date Died:________ Gallery: ©Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com January 2010 2 Famous Impressionist Artist Edgar Degas Vincent Van Gogh Georges Seurat Paul Cezanne Claude Monet Henri de ToulouseToulouse----LautrecLautrec PierrePierre----AugusteAuguste Renoir Paul Gauguin Mary Cassatt Paul Signac Alfred Sisley Camille Pissarro Bertha Morisot ©Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com January 2010 3 Edgar Degas Gallery: Little Dancer of Fourteen Years , Ballet Rehearsal, 1873 Dancers at The Bar The Singer with glove Edgar Degas (19 July 1834 – 27 September 1917), born HilaireHilaire----GermainGermainGermain----EdgarEdgar De GasGas, was a French artist famous for his work in painting , sculpture , printmaking and drawing . He is regarded as one of the founders of Impressionism although he rejected the term, and preferred to be called a realist. [1] A superb draughtsman , he is especially identified with the subject of the dance, and over half his works depict dancers. Early in his career, his ambition was to be a history painter , a calling for which he was well prepared by his rigorous academic training and close study of classic art. In his early thirties, he changed course, and by bringing the traditional methods of a history painter to bear on contemporary subject matter, he became a classical painter of modern life. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Degas ©Nadene of http://practicalpages.wordpress.com January 2010 4 Vincent Van Gogh Gallery: Bedroom in Arles The Starry Night Wheat Field with Cypresses Vincent Willem van Gogh (30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter whose work had a far-reaching influence on 20th century art for its vivid colors and emotional impact. -

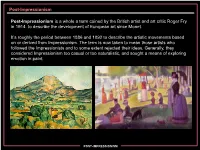

Post-Impressionism Post-Impressionism Is a Whole A

Post-Impressionism Post-Impressionism is a whole a term coined by the British artist and art critic Roger Fry in 1914, to describe the development of European art since Monet. It’s roughly the period between 1886 and 1892 to describe the artistic movements based on or derived from Impressionism. The term is now taken to mean those artists who followed the Impressionists and to some extent rejected their ideas. Generally, they considered Impressionism too casual or too naturalistic, and sought a means of exploring emotion in paint. POST-IMPRESSIONISM Post-Impressionism Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Disabled poster artist known as one of the first Graphic Designers Paul Cezanne Large block-like brushstrokes; Still lifes, Landscapes Vincent Van Gogh Distrurbed painter of loose brushstrokes and bright, vivid colors George Seurat Founder of Pointillism; Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte Paul Gauguin Rejected Urban Life and choose secondary-colored Tahitian women Auguste Rodin Bronze sculptor; Very loose and not detailed. “The Thinker”, and “Burghers of Calais” Edvard Munch Long brushstrokes to create haunting images POST-IMPRESSIONISM Post-Impressionism Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec ” At the Moulin Rouge” Art Institute of Chicago. 1895 French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864- 1901) was interested in capturing the sensibility of modern life and deeply admired Degas. Because of this interest and admiration, his work intersects with that of the Impressionists. However, his work has an added satirical edge to it and often borders on caricature. Toulouse-Latutrec’s art was, to a degree, the expression of his life. Self-exiled by his odd stature and crippled legs from the high society his ancient aristocratic name entitled him to enter, he became denizen of the night world of Paris, consorting with a tawdry population of entertainers, prostitutes, and other social outcasts. -

Sfoglia L'arte Alla Scoperta Dell'arte, in Tutte Le Sue Forme, Degli Artisti E Delle Loro Opere

SISTEMA BIBLIOTECARIO DI MONTE CLARO Mostra Bibliografica Sfoglia l'arte alla scoperta dell'arte, in tutte le sue forme, degli artisti e delle loro opere Centro Regionale di Documentazione Biblioteche per Ragazzi 20 storie a regola d'arte / a cura di Marco Dallari e Alessandra Francucci. - [Bologna] : 1 Art'è, [2000?]. - 87 p. : ill. ; 21x26 cm.(Art'è ragazzi) 3D : la scultura contemporanea: luoghi, spazi, materiali / a cura di Maura Pozzati. - 2 Bologna : Art'è, 2002. - 55 p. : ill. ; 22x27 cm.(Art'è ragazzi) A passeggio con Monet / Julie Merberg e Suzanne Bober. - San Dorligo della Valle : 3 EL, [2003!. - 1 v. : cartone, ill. ; 14x14 cm. ((Tit. della cop. A scuola col museo : guida alla didattica artistica / Renate Eco ; in collaborazione con 4 Renato Giovannoli. - Milano : Gruppo editoriale Fabbri-Bompiani-Sonzogno-ETAS, 1986. - X, 216 p. : ill. ; 19x19 cm.(Strumenti Bompiani) A scuola di arte / Mick Manning & Brita Granstrom. - Trieste : Editoriale scienza, 2000. 5 - 47 p. : ill. ; 28 cm. ((Traduzione di Laura Servidei. ABC d'arte : lettere nascoste nei quadri / Anne Guery, Olivier Dussutour. - Modena : 6 Franco Cosimo Panini, 2011. - [64] p. : in gran parte ill. ; 26x26 cm. ((Traduzione di Federica Previata.(Libri ad arte) Alberi : segni, parole, scienza e altro per un gioco ad arte / ideato e curato da Maria Flora Giubilei e Simonetta Maione ; collaborazione ai testi di Gianni Franzone ; racconto di Pia Pera ; illustrazioni di Michele Ferri ; esperto di alberi Libereso Guglielmi ; quaderno-laboratorio di Paola Ciarcià, Libereso Guglielmi e Simonetta Maione ; DVD 7 voce narrante di Pia Pera ; a cura di Enrico Pierini. - Bazzano : Artebambini, 2010. -

Open Posey Kyle 105Decisiveworks.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE 105 DECISIVE WORKS OF OCCIDENTAL ART BY MICHEL BUTOR (TRANSLATION OF FINAL 50 PAGES) KYLE ANTHONY POSEY SPRING 2019 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Comparative Literature and Art History with honors in Comparative Literature Reviewed and approved* by the following: Dr. Eric Hayot Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature and Asian Studies Honors Advisor/Thesis Supervisor Dr. Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Faculty Reader * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This honors thesis is a translation from French to English of the writer Michel Butor’s art historical survey titled 105 Oeuvres Décisives de la Peinture Occidentale. I have translated the final fifty pages, which roughly covers modern art, beginning with Post-Impressionism. The introduction covers the background to the book, problems of translation, and a note about word- image relationships and what this thesis represents to me. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... v Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter -

Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin Painter, Sculptor 1848 – 1903 • Born on June 7, 1848 in Paris, france • Mother was peruvian, family lived Peru for 4 years • Family returns to France when he is 7 • Serves in the Merchant Marine, then the French Navy • Returns to Paris and becomes a Stockbroker • Marries a danish woman and they have 5 children • They live in Copenhagen where he is a stockbroker • Paints in his free time – buys art in galleries and makes friends with artists Portrait of Madame Gauguin • Decides he wants to (1880) paint full time – leaves his family in Copenhagen and goes back to Paris • His early work is in the impressionist style which is very popular at that time • He is not very successful at his art, he is poor • Leaves France to find a simpler life on a tropical island Aline Gauguin Brothers (1883) Visits his friend Vincent vanGogh in Arles, France where they both paint They quarrel, with van Gogh famously cutting off part of his ! own ear Gauguin leaves france and never sees van Gogh again Night Café at Arles (1888) Decides he doesn’t like impressionism, prefers native art of africa and asia because it has more meaning (symbolism) He paints flat areas of color and bold outlines He lives in Tahiti and The Siesta (1892) paints images of Polynesian life Tahitian women on the beach (1891) • His art is in the Primitivist style- exaggerated body proportions, animal symbolism, geometric designs and bold contrasting colors • Gauguin is the first artist of his time to become successful with this style (so different from the popular impressionism) • His work influences other painters, especially Pablo Picasso When do you get married? (1892) Gauguin spent the remainder of his life painting and living ! in the Marquesas Islands, a very remote, jungle-like ! place in French Polynesia (close to Tahiti) Gauguin’s house, Atuona, ! Marquesas Islands Gauguin lived ! alone in the ! jungle, where ! one day his houseboy arrived to find him dead, with a smile on his face. -

Realism Impressionism Post Impressionism Week Five Background/Context the École Des Beaux-Arts

Realism Impressionism Post Impressionism week five Background/context The École des Beaux-Arts • The École des Beaux-Arts (est. 1648) was a government controlled art school originally meant to guarantee a pool of artists available to decorate the palaces of Louis XIV Artistic training at The École des Beaux-Arts • Students at the École des Beaux Arts were required to pass exams which proved they could imitate classical art. • An École education had three essential parts: learning to copy engravings of Classical art, drawing from casts of Classical statues and finally drawing from the nude model The Academy, Académie des Beaux-Arts • The École des Beaux-Arts was an adjunct to the French Académie des beaux-arts • The Academy held a virtual monopoly on artistic styles and tastes until the late 1800s • The Academy favored classical subjects painted in a highly polished classical style • Academic art was at its most influential phase during the periods of Neoclassicism and Romanticism • The Academy ranked subject matter in order of importance -History and classical subjects were the most important types of painting -Landscape was near the bottom -Still life and genre painting were unworthy subjects for art The Salons • The Salons were annual art shows sponsored by the Academy • If an artist was to have any success or recognition, it was essential achieve success in the Salons Realism What is Realism? Courbet rebelled against the strictures of the Academy, exhibiting in his own shows. Other groups of painters followed his example and began to rebel against the Academy as well. • Subjects attempt to make the ordinary into something beautiful • Subjects often include peasants and workers • Subjects attempt to show the undisguised truth of life • Realism deliberately violates the standards of the Academy.