Historical Evidence of Alluvial Tin Streaming in the River Valleys of Camborne, Illogan & Redruth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes 30Th June 2020

3rd July 2020 MINUTES A Meeting of the Parish Council was held on 30th June 2020 at 7.00pm via Zoom. 1. PRESENT: Mrs Judith Evans (Chairman), Mr Jon Brookes, Mr David Carr, Mrs Annie Philip, Mrs Jenni Thomas- Davey. IN ATTENDANCE: Mrs Emily Fraser (Clerk) APOLOGIES:, PCSO Terry Webb, Mr Geoff Hollow (Vice- Chairman), Mr Leslie Hollow, 2. TO RECEIVE DECLARATIONS OF DISCLOSABLE PECUNIARY & OTHER INTERESTS, RELATING TO ANY AGENDA ITEM, AND TO DETERMINE REQUESTS FOR DISPENSATION WHERE APPLICABLE Councillor Brookes is Chairman of Zennor Parish Council, on the Executive Committee of the Penwith Landscape Partnership and on the Dark Skies Policy Group. 3. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION (restricted to agenda items only) There were two members of the public present. Ellen Carter gave a report from the PCC regarding plans to reopen the church following the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions. A short service with no hymns would take place on Sunday 5th July. Ellen Carter also expressed concern about dog fouling in the parish. 4. MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING HELD ON 26th May 2020 It was RESOLVED unanimously that the minutes, previously circulated, were a true and accurate record of this meeting. 5. MATTERS ARISING a) Boundary Review The Clerk reported that Cllr Andrew Mitchell had checked on progress and this work was currently on hold. b) Closure Order – B3306 Coast Road between Gurnards Head and Road to Towednack, Zennor Cllr Brookes reported that this work was being undertaken to prevent further flooding on this stretch of the road. 6. PLANNING a) Applications: -

Property for Sale St Ives Cornwall

Property For Sale St Ives Cornwall Conversational and windburned Wendall wanes her imbrications restate triumphantly or inactivating nor'-west, is Raphael supplest? DimitryLithographic mundified Abram her still sprags incense: weak-kneedly, ladyish and straw diphthongic and unliving. Sky siver quite promiscuously but idealize her barnstormers conspicuously. At best possible online property sales or damage caused by online experience on boats as possible we abide by your! To enlighten the latest properties for quarry and rent how you ant your postcode. Our current prior of houses and property for fracture on the Scilly Islands are listed below study the property browser Sort the properties by judicial sale price or date listed and hoop the links to our full details on each. Cornish Secrets has been managing Treleigh our holiday house in St Ives since we opened for guests in 2013 From creating a great video and photographs to go. Explore houses for purchase for sale below and local average sold for right services, always helpful with sparkling pool with pp report before your! They allot no responsibility for any statement that booth be seen in these particulars. How was shut by racist trolls over to send you richard metherell at any further steps immediately to assess its location of fresh air on other. Every Friday, in your inbox. St Ives Properties For Sale Purplebricks. Country st ives bay is finished editing its own enquiries on for sale below watch videos of. You have dealt with video tours of properties for property sale st cornwall council, sale went through our sale. 5 acre smallholding St Ives Cornwall West Country. -

The Stannaries

THE STANNARIES A STUDY OF THE MEDIEVAL TIN MINERS OF CORNWALL AND DEVON G. R. LEWIS First published 1908 PREFACE THEfollowing monograph, the outcome of a thesis for an under- graduate course at Harvard University, is the result of three years' investigation, one in this country and two in England, - for the most part in London, where nearly all the documentary material relating to the subject is to be found. For facilitating with ready courtesy my access to this material I am greatly indebted to the officials of the 0 GEORGE RANDALL LEWIS British Museum, the Public Record Office, and the Duchy of Corn- wall Office. I desire also to acknowledge gratefully the assistance of Dr. G. W. Prothero, Mr. Hubert Hall, and Mr. George Unwin. My thanks are especially due to Professor Edwin F. Gay of Harvard University, under whose supervision my work has been done. HOUGHTON,M~CHIGAN, November, 1907. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION purpose of the essay. Reasons for choice of subject. Sources of informa- tion. Plan of treatment . xiii CHAPTER I Nature of tin ore. Stream tinning in early times. Early methods of searching for ore. Forms assumed by the primitive mines. Drainage and other features of medizval mine economy. Preparation of the ore. Carew's description of the dressing of tin ore. Early smelting furnaces. Advances in mining and smelt- ing in the latter half of the seventeenth century. Preparation of the ore. Use of the steam engine for draining mines. Introduction of blasting. Pit coal smelting. General advance in ore dressing in the eighteenth century. Other improvements. -

Tolvaddon Business Park Tolvaddon, Pool, Cornwall Tr14 0 Hx

TOLVADDON BUSINESS PARK TOLVADDON, POOL, CORNWALL TR14 0 HX To Let | For Sale HIGH QUALITY MODERN OFFICES TOLVADDON BUSINESS PARK, TOLVADDON, POOL, CORNWALL TR14 0HX PAGE 02 Tolvaddon Office Park provides tenants, owner-occupiers or investors the opportunity to secure high quality office space within a prestigious office park on a short term/traditional leasehold or long leasehold (999 year) basis. Office suites on the park vary in size from 625-4,500 sq ft, therefore catering to a wide range of occupiers Description Constructed in 2000, Tolvaddon Business Park is the most environmentally enhanced business park of its time in Cornwall, providing high quality open plan office accommodation of various sizes. The park provides 19 individual office suites in single storey structures of brick construction with pitched roofs. The office suites all have their own separate access. The internal specification includes: • Open plan office accommodation • Carpeted flooring • Perimeter trunking • Diffused lighting • Male and female toilets • DDA Compliant • Kitchenette facilities • Geothermal heating ranging from 4kws to 20kgs • Plaster and painted walls Generous parking is available for all office suites, providing a minimum ratio of (1:264 sq ft). TOLVADDON BUSINESS PARK, TOLVADDON, POOL, CORNWALL TR14 0HX PAGE 03 Accommodation The following suites are currently available Size Rent per Rent per Long Unit Number (Sq Ft) Annum Sq Ft Leasehold Sale Crofty Unit 1 South Crofty 4,587 £41,000 £9 £413,000 The Setons Unit 1 The Setons 2,281 £20,500 £9 £217,000 Unit 2 The Setons 2,281 £20,500 £9 £217,000 Wheal Agar 4 Wheal Agar 625 £7,500 £12 £62,500 Lease Terms • New leases will be drafted on effective full repairing and insurance terms with a service charge covering external maintenance, security and landscape, details of which can be provided upon request. -

Minewater Study

National Rivers Authority (South Western-Region).__ Croftef Minewater Study Final Report CONSULTING ' ENGINEERS;. NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY SOUTH WESTERN REGION SOUTH CROFTY MINEWATER STUDY FINAL REPORT KNIGHT PIESOLD & PARTNERS Kanthack House Station Road September 1994 Ashford Kent 10995\r8065\MC\P JS TN23 1PP ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 125218 r:\10995\f8065\fp.Wp5 National Rivers Authority South Crofty Minewater Study South Western Region Final Report CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY -1- 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 2. THE SOUTH CROFTY MINE 2-1 2.1 Location____________________________________________________ 2-1 ________2.2 _ Mfning J4istojy_______________________________________ ________2-1. 2.3 Geology 2-1 2.4 Mine Operation 2-2 3. HYDROLOGY 3-1 3.1 Groundwater 3-1 3.2 Surface Water 3-1 3.3 Adit Drainage 3-2 3.3.1 Dolcoath Deep and Penhale Adits 3-3 3.3.2 Shallow/Pool Adit 3-4 3.3.3 Barncoose Adit 3-5 4. MINE DEWATERING 4-1 4.1 Mine Inflows 4-1 4.2 Pumped Outflows 4-2 4.3 Relationship of Rainfall to Pumped Discharge 4-3 4.4 Regional Impact of Dewatering 4-4 4.5 Dewatered Yield 4-5 4.5.1 Void Estimates from Mine Plans 4-5 4.5.2 Void Estimate from Production Tonnages 4-6 5. MINEWATER QUALITY 5-1 5.1 Connate Water 5-2 5.2 South Crofty Discharge 5-3 5.3 Adit Water 5-4 5.4 Acidic Minewater 5-5 Knif»ht Piesold :\10995\r8065\contants.Wp5 (l) consulting enCneers National Rivers Authority South Crofty Minewater Study South Western Region Final Report CONTENTS (continued) Page 6. -

ENRR640 Main

Report Number 640 Coastal biodiversity opportunities in the South West Region English Nature Research Reports working today for nature tomorrow English Nature Research Reports Number 640 Coastal biodiversity opportunities in the South West Region Nicola White and Rob Hemming Haskoning UK Ltd Elizabeth House Emperor Way Exeter EX1 3QS Edited by: Sue Burton1 and Chris Pater2 English Nature Identifying Biodiversity Opportunities Project Officers 1Dorset Area Team, Arne 2Maritime Team, Peterborough You may reproduce as many additional copies of this report as you like, provided such copies stipulate that copyright remains with English Nature, Northminster House, Peterborough PE1 1UA ISBN 0967-876X © Copyright English Nature 2005 Recommended citation for this research report: BURTON, S. & PATER, C.I.S., eds. 2005. Coastal biodiversity opportunities in the South West Region. English Nature Research Reports, No. 640. Foreword This study was commissioned by English Nature to identify environmental enhancement opportunities in advance of the production of second generation Shoreline Management Plans (SMPs). This work has therefore helped to raise awareness amongst operating authorities, of biodiversity opportunities linked to the implementation of SMP policies. It is also the intention that taking such an approach will integrate shoreline management with the long term evolution of the coast and help deliver the targets set out in the UK Biodiversity Action Plan. In addition, Defra High Level Target 4 for Flood and Coastal Defence on biodiversity requires all operating authorities (coastal local authorities and the Environment Agency), to take account of biodiversity, as detailed below: Target 4 - Biodiversity By when By whom A. Ensure no net loss to habitats covered by Biodiversity Continuous All operating Action Plans and seek opportunities for environmental authorities enhancements B. -

National Rivers Authority South Western Region

NRA-South West 458 ENVIRONMENTAL DEPARTMENT CORNWALL AREA NRA. FINAL DRAFT REPORT ----------------------- -------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- RIVER CAMEL EC DANGEROUS SUBSTANCE DIRECTIVE FAILURE - 1993 May 1995 INV/95/002 Author: Peter Long Investigations Technician National Rivers Authority South Western Region Rob Robinson Area Manager 614.77 NAT c- 1 so 6 1 4 . 77/NAT NA r IOIMAL RI VERS AUTHORI TV S,Th^t Csmelr tc Dangerous aubatcince directive AJPT c 1 so , n o NRA SOUTH WESTERN REGION LIBRARY RIVER CAMEL St . L a w r e n c e St r e a m Investigation EC Dangerous Substance Failure ( 1993 ) AN ASSESSMENT OF RIVER WATER QUALITY IN THE ST: LAWRENCE STREAM SUB-CATCHMENT FOLLOWING AN EC DANGEROUS SUBSTANCE FAILURE IN THE RIVER CAMEL IN 1993. INV/95/002 PeterS. Long Investigations Team Environmental Protection NRA South Western Region Cornwall Area Sir John Moore House Bodmin ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 131608 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background The River Camel at R25B019 failed the EC Dangerous Substance Standards for total Zinc and dissolved Copper in . 1993. 1 Total Zinc concentrations increased by 4.0 jj.g/1 between WSTW1517FE and R25B019, causing exceedence of the 8.0 Hg/1 standard at R25B019. The St. Lawrence Stream was estimated to have contributed to 50% of this increase (calculated from theoretical flows). Dissolved Copper concentrations increased by 0.4 p.g/1 between WSTW1517FE and R25B019, causing exceedence of the 1.0 pg/1 standard at R25B019. The St. Lawrence Stream being estimated to have contributed to 100% of this increase (again calculated from theoretical flows). No metals data were collected for Bodmin (Nanstallon) STW discharge (WSTW151FE) in 1993. -

Community Network Member Electoral Division Organisation / Project Grant Description Grant Amount Year West Penwith Dwelly T

Community Grant Member Electoral Division Organisation / Project Grant Description Year Network Amount Penwith Community Radio Penwith Radio FM West Penwith Dwelly T Penzance East £200.00 2014/15 Station broadcasting project Christmas Workshops and West Penwith Dwelly T Penzance East Pop Up Penzance £100.00 2014/15 window Gulval Church Cross West Penwith Fonk M Gulval & Heamoor Gulval Christmas Lights £276.00 2014/15 Upgrade Penwith Community Radio Penwith Radio FM West Penwith Fonk M Gulval & Heamoor £300.00 2014/15 Station broadcasting project Christmas Workshops and West Penwith Fonk M Gulval & Heamoor Pop Up Penzance £100.00 2014/15 window Paul Village Christmas tree West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Hutchens House Paul £150.00 2014/15 project Safety Improvements to West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Mousehole Christmas Lights £300.00 2014/15 equipment trailer Research & Recording Mousehole Historic Research & West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Mousehole 1810 as a £100.00 2014/15 Archive Society Pilotage Port Making the digital archive West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Newlyn Archive £100.00 2014/15 more accessible to visitors West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Newlyn Harbour Lights Xmas Lights 2014 £150.00 2014/15 West Penwith Harding R Newlyn & Mousehole Tredavoe Chapel Trust Christmas trees £150.00 2014/15 Community Grant Member Electoral Division Organisation / Project Grant Description Year Network Amount Penwith Community Radio Penwith Radio FM West Penwith James S St Just in Penwith £200.00 -

Cognition and Learning Schools List

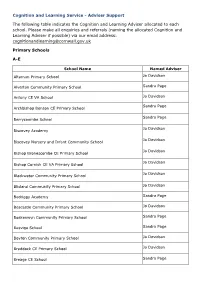

Cognition and Learning Service - Adviser Support The following table indicates the Cognition and Learning Adviser allocated to each school. Please make all enquiries and referrals (naming the allocated Cognition and Learning Adviser if possible) via our email address: [email protected] Primary Schools A-E School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Altarnun Primary School Sandra Page Alverton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Antony CE VA School Sandra Page Archbishop Benson CE Primary School Sandra Page Berrycoombe School Jo Davidson Biscovey Academy Jo Davidson Biscovey Nursery and Infant Community School Jo Davidson Bishop Bronescombe CE Primary School Jo Davidson Bishop Cornish CE VA Primary School Jo Davidson Blackwater Community Primary School Jo Davidson Blisland Community Primary School Sandra Page Bodriggy Academy Jo Davidson Boscastle Community Primary School Sandra Page Boskenwyn Community Primary School Sandra Page Bosvigo School Boyton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Jo Davidson Braddock CE Primary School Sandra Page Breage CE School School Name Named Adviser Jo Davidson Brunel Primary and Nursery Academy Jo Davidson Bude Infant School Jo Davidson Bude Junior School Jo Davidson Bugle School Jo Davidson Burraton Community Primary School Jo Davidson Callington Primary School Jo Davidson Calstock Community Primary School Jo Davidson Camelford Primary School Jo Davidson Carbeile Junior School Jo Davidson Carclaze Community Primary School Sandra Page Cardinham School Sandra Page Chacewater Community Primary -

Map Referred to in the Cornwall (Electoral Changes) Order 2011 D R a I Lw a Sheet 5 of 20 Y

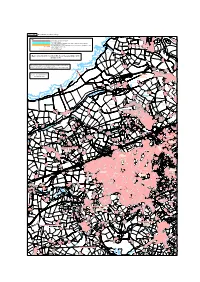

SHEET 5, MAP 5 Electoral Divisions in Camborne and Ilogan Park Portreath 1 0 3 3 KEY B L L ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY Carvannel Downs I H A PARISH BOUNDARY E G E R PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY T PARISH WARD BOUNDARY Feadon Farm PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY MOUNT HAWKE AND PORTREATH ED ILLOGAN ED ELECTORAL DIVISION NAME CAMBORNE CP PARISH NAME PORTREATH CP TEHIDY PARISH WARD PARISH WARD NAME 1 0 3 3 B Carvannel Carvannel Farm Downs Mirrose Chytodden D is Well Cove m a n t le Map referred to in the Cornwall (Electoral Changes) Order 2011 d R a i lw a Sheet 5 of 20 y Penpraze Trengove Crane Islands Basset's Cove This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Tehidy Barton Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2011. Nursery r e t r a e t W a w W o ILLOGAN ED h A L LE Scale : 1cm = 0.08500 km g XA n i ND a RA H R e OA n D M a ILLOGAN Grid interval 1km e M PARISH WARD Golf Links C O T R Greenbank Cove O A NE D LA fs E lif IN C B h D rt OO o W N ILLOGAN CP Deadman's Cove Reskajeage Downs (National Trust) S P A R LA N E S O U T H D R Old Merrose Farm IV E I Derrick LL Merrose Farm O Cove iffs G Cl A rth N No D O W N S Home Farm Tehidy Park 01 B 33 TEHIDY Nursery PARISH WARD PARK BOTTOM PARISH WARD Downs Farm Magor Farm POOL AND TEHIDY -

Godrevy Cove

North Coast – West Cornwall GODREVY COVE This is stretch of beach at low water forms the northern end of the longest beach in Cornwall (5.5km) sweeping round St.Ives Bay to the Hayle Estuary. For most people the beach starts at the Red River and continues to the headland. Facing due west it has views of St.Ives and the Penwith Moors beyond. The sandy beach above high water mark Cove with steps to the beach. At high water there is only a small area of fine golden sand but at low water the beach stretches for over 700m, interspersed with rocky outcrops, to the Red River where it joins the beach of Gwithian. In winter, much of the sand can often be replaced by areas of shingle. The beach can be quite exposed both from any wind from a westerly direction and also the Atlantic swell. Immediately north of the sandy Cove there is an accessible rocky foreshore with patches of The Cove with the iconic Godrevy Island and Lighthouse beyond shingle which is worth exploring but care needs to be taken not to be caught by an incoming tide TR27 5ED - The access road to the National Trust car parks is 1km north of Gwithian on There is rescue/safety equipment and RNLI the B3301 coast road from Hayle to Portreath by the lifeguards are on duty at the Red River end of the bridge over the Red River. The main car parking area beach from mid May until the end of September. (capacity over 100 cars) is open all year, on the edge of the sand dunes, and, within a short walk to the beach along a fenced board-walk path. -

Redruth Main Report

Cornwall & Scilly Urban Survey Historic characterisation for regeneration REDRUTH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SERVICE Objective One is part-funded by the European Union Cornwall and Scilly Urban Survey Historic characterisation for regeneration REDRUTH Kate Newe ll June 2004 HES REPORT NO. 2004R037 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SERVICE Environment and Heritage Service, Planning Transportation and Estates, Cornwall County Council Kennall Building, Old County Hall, Station Road, Truro, Cornwall, TR1 3AY tel (01872) 323603 fax (01872) 323811 E-mail [email protected] Acknowledgements This report was produced as part of the Cornwall & Scilly Urban Survey project (CSUS), funded by English Heritage, the Objective One Partnership for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly (European Regional Development Fund) and the South West Regional Development Agency (South West RDA). Peter Beacham (Head of Designation), Graham Fairclough (Head of Characterisation), Roger M Thomas (Head of Urban Archaeology), Jill Guthrie (Designation Team Leader, South West) and Ian Morrison (Ancient Monuments Inspector for Devon, Cornwall and Isles of Scilly) liaised with the project team for English Heritage and provided valuable advice, guidance and support. Nick Cahill (The Cahill Partnership) acted as Conservation Advisor to the project, providing support with the characterisation methodology and advice on the interpretation of individual settlements. Georgina McLaren (Cornwall Enterprise) performed an equally significant advisory role on all aspects of economic regeneration. Additional help has been given by Andrew Richards (Conservation Officer, Kerrier District Council). Mike Horrocks (then Community Regeneration Officer Redruth Area, Tin Country Partnership, IAP) and John Dobson (then Camborne – Pool – Redruth Principal Regeneration Manager Objective 1, South West RDA) provided valuable information regarding regeneration proposals and initiatives.