Language Unlocks Reading: Supporting Early Language and Reading for Every Child

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Look at Linguistic Readers

Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts Volume 10 Issue 3 April 1970 Article 5 4-1-1970 A Look At Linguistic Readers Nicholas P. Criscuolo New Haven, Connecticut Public Schools Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Criscuolo, N. P. (1970). A Look At Linguistic Readers. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 10 (3). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol10/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Education and Literacy Studies at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. A LOOK AT LINGUISTIC READERS Nicholas P. Criscuolo NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT, PUBLIC SCHOOLS Linguistics, as it relates to reading, has generated much interest lately among educators. Although linguistics is not a new science, its recent focus has captured the interest of the reading specialist because both the specialist and the linguist are concerned with language. This surge of interest in linguistics becomes evident when one sees that a total of forty-four articles on linguistics are listed in the Education Index for July, 1965 to June, 1966. The number of articles on linguistics written for educational journals has been increasing ever SInce. This interest has been sharpened to some degree by the publi cation of Chall's book Learning to Read: The Great Debate (1). -

Similarities and Differences Between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Similarities and Differences between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology Yuki Itani-Adams1, Junko Iwasaki2, Satomi Kawaguchi3* 1ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2601, Australia 2School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, 2 Bradford Street, Mt Lawley WA 6050, Australia 3School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Bullecourt Ave, Milperra NSW 2214, Australia Corresponding Author: Satomi Kawaguchi , E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This paper compares the acquisition of Japanese morphology of two bilingual children who had Received: June 14, 2017 different types of exposure to Japanese language in Australia: a simultaneous bilingual child Accepted: August 14, 2017 who had exposure to both Japanese and English from birth, and a successive bilingual child Published: December 01, 2017 who did not have regular exposure to Japanese until he was six years and three months old. The comparison is carried out using Processability Theory (PT) (Pienemann 1998, 2005) as a Volume: 6 Issue: 7 common framework, and the corpus for this study consists of the naturally spoken production Special Issue on Language & Literature of these two Australian children. The results show that both children went through the same Advance access: September 2017 developmental path in their acquisition of the Japanese morphological structures, indicating that the same processing mechanisms are at work for both types of language acquisition. However, Conflicts of interest: None the results indicate that there are some differences between the two children, including the rate Funding: None of acquisition, and the kinds of verbal morphemes acquired. -

Learning About Phonology and Orthography

EFFECTIVE LITERACY PRACTICES MODULE REFERENCE GUIDE Learning About Phonology and Orthography Module Focus Learning about the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language (often referred to as letter-sound associations, graphophonics, sound- symbol relationships) Definitions phonology: study of speech sounds in a language orthography: study of the system of written language (spelling) continuous text: a complete text or substantive part of a complete text What Children Children need to learn to work out how their spoken language relates to messages in print. Have to Learn They need to learn (Clay, 2002, 2006, p. 112) • to hear sounds buried in words • to visually discriminate the symbols we use in print • to link single symbols and clusters of symbols with the sounds they represent • that there are many exceptions and alternatives in our English system of putting sounds into print Children also begin to work on relationships among things they already know, often long before the teacher attends to those relationships. For example, children discover that • it is more efficient to work with larger chunks • sometimes it is more efficient to work with relationships (like some word or word part I know) • often it is more efficient to use a vague sense of a rule How Children Writing Learn About • Building a known writing vocabulary Phonology and • Analyzing words by hearing and recording sounds in words Orthography • Using known words and word parts to solve new unknown words • Noticing and learning about exceptions in English orthography Reading • Building a known reading vocabulary • Using known words and word parts to get to unknown words • Taking words apart while reading Manipulating Words and Word Parts • Using magnetic letters to manipulate and explore words and word parts Key Points Through reading and writing continuous text, children learn about sound-symbol relation- for Teachers ships, they take on known reading and writing vocabularies, and they can use what they know about words to generate new learning. -

Syllabus 1 Lín Táo 林燾 and Gêng Zhènshëng 耿振生

CHINESE 542 Introduction to Chinese Historical Phonology Spring 2005 This course is a basic introduction at the graduate level to methods and materials in Chinese historical phonology. Reading ability in Chinese is required. It is assumed that students have taken Chinese 342, 442, or the equivalent, and are familiar with articulatory phonetics concepts and terminology, including the International Phonetic Alphabet, and with general notions of historical sound change. Topics covered include the periodization of the Chinese language; the source materials for reconstructing earlier stages of the language; traditional Chinese phonological categories and terminology; fânqiè spellings; major reconstruction systems; the use of reference materials to determine reconstructions in these systems. The focus of the course is on Middle Chinese. Class: Mondays & Fridays 3:30 - 5:20, Savery 335 Web: http://courses.washington.edu/chin532/ Instructor: Zev Handel 245 Gowen, 543-4863 [email protected] Office hours: MF 2-3pm Grading: homework exercises 30% quiz 5% comprehensive test 25% short translations 15% annotated translation 25% Readings: Readings are available on e-reserves or in the East Asian library. Items below marked with a call number are on reserve in the East Asian Library or (if the call number starts with REF) on the reference shelves. Items marked eres are on course e-reserves. Baxter, William H. 1992. A handbook of Old Chinese phonology. (Trends in linguistics: studies and monographs, 64.) Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. PL1201.B38 1992 [eres: chapters 2, 8, 9] Baxter, William H. and Laurent Sagart. 1998 . “Word formation in Old Chinese” . In New approaches to Chinese word formation: morphology, phonology and the lexicon in modern and ancient Chinese. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Shallow Vs Non-Shallow Orthographies and Learning to Read Workshop 28-29 September 2005

A Report of the OECD-CERI LEARNING SCIENCES AND BRAIN RESEARCH Shallow vs Non-shallow Orthographies and Learning to Read Workshop 28-29 September 2005 St. John’s College Cambridge University UK Co-hosted by The Centre for Neuroscience in Education Cambridge University Report prepared by Cassandra Davis OECD, Learning Sciences and Brain Research Project 1 Background information The goal of this report of this workshop is to: • Provide an overview of the content of the workshop presentations. • Present a summary of the discussion on cross-language differences in learning to read and the future of brain science research in this arena. N.B. The project on "Learning Sciences and Brain Research" was introduced to the OECD's CERI Governing Board on 23 November 1999, outlining proposed work for the future. The purpose of this novel project was to create collaboration between the learning sciences and brain research on the one hand, and researchers and policy makers on the other hand. The CERI Governing Board recognised this as a risk venture, as most innovative programmes are, but with a high potential pay-off. The CERI Secretariat and Governing Board agreed in particular that the project had excellent potential for better understanding learning processes over the lifecycle, but that ethical questions also existed. Together these potentials and concerns highlighted the need for dialogue between the different stakeholders. The project is now in its second phase (2002- 2005), and has channelled its activities into 3 networks (literacy, numeracy and lifelong learning) using a three dimensional approach: problem-focused; trans-disciplinary; and international. -

Reading Depends on Writing, in Chinese

Reading depends on writing, in Chinese Li Hai Tan*, John A. Spinks†, Guinevere F. Eden‡, Charles A. Perfetti§, and Wai Ting Siok*¶ *Department of Linguistics, and †Vice Chancellor’s Office, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China; ‡Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC 20057; and §Learning Research and Development Center, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 12560 Communicated by Robert Desimone, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, April 28, 2005 (received for review January 3, 2005) Language development entails four fundamental and interactive this argument are two characteristics of the Chinese language: (i) abilities: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Over the past Spoken Chinese is highly homophonic, with a single syllable four decades, a large body of evidence has indicated that reading shared by many words, and (ii) the writing system encodes these acquisition is strongly associated with a child’s listening skills, homophonic syllables in its major graphic unit, the character. particularly the child’s sensitivity to phonological structures of Thus, when learning to read, a Chinese child is confronted with spoken language. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that the the fact that a large number of written characters correspond to close relationship between reading and listening is manifested the same syllable (as depicted in Fig. 1A), and phonological universally across languages and that behavioral remediation information is insufficient to access semantics of a printed using strategies addressing phonological awareness alleviates character. reading difficulties in dyslexics. The prevailing view of the central In addition to these system-level (language and writing system) role of phonological awareness in reading development is largely factors, Chinese writing presents some script-level features that based on studies using Western (alphabetic) languages, which are distinguish it visually from alphabetic systems. -

The Activation of Phonology During Silent Chinese Word Reading

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Copyright 1999 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. Learning, Memory', and Cognition 0278-7393/99/S3.0O 1999, Vol. 25, No. 4,838-857 The Activation of Phonology During Silent Chinese Word Reading Yaoda Xu Alexander Pollatsek Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Massachusetts at Amherst Mary C. Potter Massachusetts Institute of Technology The role of phonology in silent Chinese compound-character reading was studied in 2 experiments using a semantic relatedness judgment task. There was significant interference from a homophone of a "target" word that was semantically related to an initially presented cue word whether the homophone was orthographically similar to the target or not This interference was only observed for exact homophones (i.e., those that had the same tone, consonant, and vowel). In addition, the effect was not significantly modulated by target or distractor frequency, nor was it restricted to cases of associative priming. Substantial interference was also found from orthographically similar nonhomophones of the targets. Together these data are best accounted for by a model that allows for parallel access of semantics via 2 routes, 1 directly from orthography to semantics and the other from orthography to phonology to semantics. The initial acquisition of most languages (with the orthography to meaning and two indirect routes to meaning important exception of sign language) is through speech. via a phonological representation, one based on spelling-to- When humans develop secondary verbal skills—reading and sound rules or regularities (a "prelexical" route) and the writing—it is unclear whether they establish a direct link other based on orthographic identification of a lexical entry from orthography to meaning or whether orthography is that leads to the activation of the word's phonological linked to phonology, with phonology remaining the sole or representation (a "postlexical" route). -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

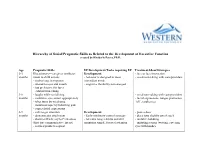

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives An effectively written language objective: • Stems form the linguistic demands of a standards-based lesson task • Focuses on high-leverage language that will serve students in other contexts • Uses active verbs to name functions/purposes for using language in a specific student task • Specifies target language necessary to complete the task • Emphasizes development of expressive language skills, speaking and writing, without neglecting listening and reading Sample language objectives: Students will articulate main idea and details using target vocabulary: topic, main idea, detail. Students will describe a character’s emotions using precise adjectives. Students will revise a paragraph using correct present tense and conditional verbs. Students will report a group consensus using past tense citation verbs: determined, concluded. Students will use present tense persuasive verbs to defend a position: maintain, contend. Language Objective Frames: Students will (function: active verb phrase) using (language target) . Students will use (language target) to (function: active verb phrase) . Active Verb Bank to Name Functions for Expressive Language Tasks articulate defend express narrate share ask define identify predict state compose describe justify react to summarize compare discuss label read rephrase contrast elaborate list recite revise debate explain name respond write Language objectives are most effectively communicated with verb phrases such as the following: Students will point out similarities between… Students will express agreement… Students will articulate events in sequence… Students will state opinions about…. Sample Noun Phrases Specifying Language Targets academic vocabulary complete sentences subject verb agreement precise adjectives complex sentences personal pronouns citation verbs clarifying questions past-tense verbs noun phrases prepositional phrases gerunds (verb + ing) 2011 Kate Kinsella, Ed.D. -

Specific Language Impairment As Systemic Developmental Disorders Christophe Parisse, Christelle Maillart

Specific language impairment as systemic developmental disorders Christophe Parisse, Christelle Maillart To cite this version: Christophe Parisse, Christelle Maillart. Specific language impairment as systemic developmental dis- orders. Journal of Neurolinguistics, Elsevier, 2009, 22, pp.109-122. 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2008.07.004. halshs-00353028 HAL Id: halshs-00353028 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00353028 Submitted on 14 Jan 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Specific language impairment as systemic developmental disorders Christophe Parisse1 and Christelle Maillart2 1- INSERM-MoDyCo, CNRS, Paris X Nanterre University 2- University of Liège 1 Abstract Specific Language Impairment (SLI) is a disorder characterised by slow, abnormal language development. Most children with this disorder do not present any other cognitive or neurological deficits. There are many different pathological developmental profiles and switches from one profile to another often occur. An alternative would be to consider SLI as a generic name covering three developmental language disorders: developmental verbal dyspraxia, linguistic dysphasia, and pragmatic language impairment. The underlying cause of SLI is unknown and the numerous studies on the subject suggest that there is no single cause. We suggest that SLI is the result of an abnormal development of the language system, occurring when more than one part of the system fails, thus blocking the system’s natural compensation mechanisms.