Anticipating Trouble: Congressional Primaries and Incumbent Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Institutional Report to the University Senate of the United Methodist Church Volume II: Self-Study Report to the Higher Learning Commission NCA, 2014

1 Institutional Report to The University Senate of The United Methodist Church Volume II: Self-Study Report to the Higher Learning Commission NCA, 2014 Submitted by Dr. Roderick L. Smothers, President Philander Smith College Little Rock, Arkansas 72202 August 2015 2 2014 Self-Study Report PREPARED FOR THE HIGHER LEARNING COMMISSION OF NCA Submitted by Dr. Lloyd E. Hervey Interim President September 2014 3 2014 Self-Study Report Developed for the Higher Learning Commission Of the North Central Association by the 2012-2014 PSC HLC Self-Study Committee Mission Statement Philander Smith College’s mission is to graduate academically accomplished students, grounded as advocates for social justice, determined to change the world for the better 4 President’s Welcome Philander Smith College (PSC) welcomes the team from the Higher Learning Commission (HLC) to our campus in Little Rock, Arkansas. It is our pleasure to provide the HLC with our Self-Study Report for 2007 -2014. This report is the work of the Philander Smith College community of learners who are ―moving forward‖ with an emphasis on ―creating a measurable and sustainable academic culture on our campus.‖ The College‘s mission is to ―graduate academically accomplished students, grounded as advocates for social justice, determined to change the world for the better.‖ As a four-year liberal arts institution with a strong Christian heritage and strong ties to the United Methodist Church, Philander Smith College is committed to offer our students the highest quality education in collaboration with the Higher Learning Commission because we believe that higher education is the key to economic, social, political, and personal empowerment. -

New Faces in the Senate

NEW FACES IN THE SENATE Kelly Ayotte (R-NH) Mark Kirk (R-IL) Replaces retiring Senator Judd Gregg (R) Replaces retiring Senator Roland Burris (D) Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) Mike Lee (R-UT) Replaces retiring Senator Christopher Dodd (D) Defeated Senator Bob Bennett (R) in the primary Roy Blunt (R-MO) Jerry Moran (R-KS) Replaces retiring Senator Kit Bond (R) Replaces retiring Senator Sam Brownback (R) John Boozman (R-AR) Rand Paul (R-KY) Replaces defeated Senator Blanche Lincoln (D) Replaces retiring Senator Jim Bunning (R) Dan Coats (R-IN) Rob Portman (R-OH) Replaces retiring Senator Evan Bayh (D) Replaces retiring Senator George Voinovich (R) Chris Coons (D-DE) Marco Rubio (R-FL) Replaces retiring Senator Ted Kaufman (D) Replaces retiring Senator George LeMieux (R) John Hoeven (R-ND) Pat Toomey (R-PA) Replaces retiring Senator Byron Dorgan (D) Replaces Senator Arlen Specter (D), who was defeated in the primary Ron Johnson (R-WI) Defeated Senator Russ Feingold (D) ARKANSAS – John Boozman (R) Defeated incumbent Senator Blanche Lincoln (D). Senator-elect John Boozman comes to the U.S. Senate after serving 5 terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from the Third District of Arkansas. Boozman served as Assistant Whip to Eric Cantor and on the Foreign Affairs Committee, including the Africa and Global Health subcommittee. Prior to his political career, Dr. Boozman ran an optometry clinic in Arkansas. Senator-elect Boozman has been a strong leader on many issues related to International Affairs programs, particularly on global health. He is the founder of the Congressional Malaria and Neglected Tropical Disease Caucus and was awarded the Congressional Leadership Award by the “The goal is to Global Health Council for his work in 2010. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Congressional Pictorial Directory.Indb I 5/16/11 10:19 AM Compiled Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing Gregg Harper, Chairman

S. Prt. 112-1 One Hundred Twelfth Congress Congressional Pictorial Directory 2011 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 2011 congressional pictorial directory.indb I 5/16/11 10:19 AM Compiled Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing Gregg Harper, Chairman For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800; Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-087912-8 online version: www.fdsys.gov congressional pictorial directory.indb II 5/16/11 10:19 AM Contents Photographs of: Page President Barack H. Obama ................... V Vice President Joseph R. Biden, Jr. .............VII Speaker of the House John A. Boehner ......... IX President pro tempore of the Senate Daniel K. Inouye .......................... XI Photographs of: Senate and House Leadership ............XII-XIII Senate Officers and Officials ............. XIV-XVI House Officers and Officials ............XVII-XVIII Capitol Officials ........................... XIX Members (by State/District no.) ............ 1-152 Delegates and Resident Commissioner .... 153-154 State Delegations ........................ 155-177 Party Division ............................... 178 Alphabetical lists of: Senators ............................. 181-184 Representatives ....................... 185-197 Delegates and Resident Commissioner ........ 198 Closing date for compilation of the Pictorial Directory was March 4, 2011. * House terms not consecutive. † Also served previous Senate terms. †† Four-year term, elected 2008. congressional pictorial directory.indb III 5/16/11 10:19 AM congressional pictorial directory.indb IV 5/16/11 10:19 AM Barack H. Obama President of the United States congressional pictorial directory.indb V 5/16/11 10:20 AM congressional pictorial directory.indb VI 5/16/11 10:20 AM Joseph R. -

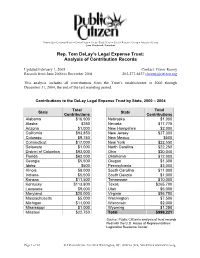

Analysis of Contribution Records

Buyers Up • Congress Watch • Critical Mass • Global Trade Watch • Health Research Group • Litigation Group Joan Claybrook, President Rep. Tom DeLay’s Legal Expense Trust: Analysis of Contribution Records Updated February 1, 2005 Contact: Conor Kenny Records from June 2000 to December 2004 202-277-6427 [email protected] This analysis includes all contributions from the Trust’s establishment in 2000 through December 31, 2004, the end of the last reporting period. Contributions to the DeLay Legal Expense Trust by State, 2000 – 2004 Total Total State State Contributions Contributions Alabama $16,900 Nebraska $1,000 Alaska $250 Nevada $17,775 Arizona $1,000 New Hampshire $2,000 California $93,850 New Jersey $27,300 Colorado $9,750 New Mexico $500 Connecticut $17,000 New York $22,550 Delaware $1,000 North Carolina $22,250 District of Columbia $93,000 Ohio $20,040 Florida $63,000 Oklahoma $12,000 Georgia $5,500 Oregon $1,300 Idaho $500 Pennsylvania $3,000 Illinois $8,000 South Carolina $11,000 Indiana $5,500 South Dakota $1,000 Kansas $11,500 Tennessee $10,000 Kentucky $113,800 Texas $265,700 Louisiana $9,000 Utah $5,000 Maryland $20,000 Virginia $56,750 Massachusetts $5,000 Washington $7,506 Michigan $11,000 Wisconsin $2,000 Mississippi $1,000 Wyoming $1,250 Missouri $22,750 Total $999,221 Source: Public Citizen’s analysis of trust records filed with the U.S. House of Representatives Legislative Resource Center. Page 1 of 12 215 Pennsylvania Ave SE • Washington, DC 20003 • (202) 546-4996 • www.citizen.org Contributions to the DeLay Legal Expense Trust by Members of Congress or Their Political Action Committees, 2000 – 2004 Total Total Member of Congress Member of Congress Contributions Contributions Rep. -

STANDING COMMITTEES of the SENATE Agriculture, Nutrition, And

STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE SENATE [Republicans in roman; Democrats in italic; Independents in SMALL CAPS] [Room numbers beginning with SD are in the Dirksen Building, SH in the Hart Building, SR in the Russell Building, and S in The Capitol] Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry 328A Russell Senate Office Building 20510–6000 phone 224–6901, fax 224–9287, TTY/TDD 224–2587 http://agriculture.senate.gov meets first and third Wednesdays of each month Tom Harkin, of Iowa, Chairman. Patrick J. Leahy, of Vermont. Richard G. Lugar, of Indiana. Kent Conrad, of North Dakota. Jesse Helms, of North Carolina. Thomas A. Daschle, of South Dakota. Thad Cochran, of Mississippi. Max Baucus, of Montana. Mitch McConnell, of Kentucky. Blanche Lincoln, of Arkansas. Pat Roberts, of Kansas. Zell Miller, of Georgia. Peter Fitzgerald, of Illinois. Debbie Stabenow, of Michigan. Craig Thomas, of Wyoming. E. Benjamin Nelson, of Nebraska. Wayne Allard, of Colorado. Mark Dayton, of Minnesota. Tim Hutchinson, of Arkansas. Paul Wellstone, of Minnesota. Mike Crapo, of Idaho. SUBCOMMITTEES [The chairman and ranking minority member are ex officio (non-voting) members of all subcommittees on which they do not serve.] Forestry, Conservation, and Rural Revitalization Blanche Lincoln, of Arkansas, Chair. Patrick J. Leahy, of Vermont. Mike Crapo, of Idaho. Thomas A. Daschle, of South Dakota. Mitch McConnell, of Kentucky. Max Baucus, of Montana. Craig Thomas, of Wyoming. Debbie Stabenow, of Michigan. Wayne Allard, of Colorado. Mark Dayton, of Minnesota. Tim Hutchinson, of Arkansas. Marketing, Inspection, and Product Promotion Max Baucus, of Montana, Chairman. Patrick J. Leahy, of Vermont. Peter Fitzgerald, of Illinois. Kent Conrad, of North Dakota. -

Advocatevolume 20, Number 5 September/October 2006 the Most Partisan Time of the Year Permanent Repeal of the Estate Tax Falls Victim to Congressional Battle

ADVOCATEVolume 20, Number 5 September/October 2006 The Most Partisan Time of the Year Permanent repeal of the estate tax falls victim to congressional battle By Jody Milanese Government Affairs Manager s the 109th Congress concludes— with only a possible lame-duck Asession remaining—it is unlikely Senate Majority Leader William Frist (R-Tenn.) will bring the “trifecta” bill back to the Senate floor. H.R. 5970 combines an estate tax cut, minimum wage hike and a package of popular tax policy extensions. The bill fell four votes short in August. Frist switched his vote to no dur- ing the Aug. 3 consideration of the Estate Tax and Extension of Tax Relief Act of 2006, which reserved his right COURTESY ISTOCKPHOTO as Senate leader to bring the legisla- The estate tax—and other parts of the current tax system—forces business owners to tion back to the floor. Despite Frist’s pay exorbitant amounts of money to the government and complete myriad forms. recent statement that “everything is any Democrats who voted against that, as of now, there is no intension on the table” for consideration prior the measure would switch their of separating elements of the trifecta to the November mid-term elections, position in an election year. package before a lame-duck session. many aides are doubtful the bill can Frist has given a task force of Since failing in the Senate in be altered enough to garner three four senators—Finance Chairman August, there has been wide debate more supporters. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), Budget over the best course of action to take Senate Minority Leader Harry Chairman Judd Gregg (R-N.H.), in achieving this top Republican pri- Reid (D-Nev.) has pushed hard to Policy Chairman Jon Kyl (R-Ariz.) ority. -

State Delegations

STATE DELEGATIONS Number before names designates Congressional district. Democrats in roman; Republicans in italic; Independent in SMALL CAPS; Independent Democrat in SMALL CAPS ITALIC; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface. ALABAMA SENATORS 2. Terry Everett Richard C. Shelby 3. Mike Rogers Jeff Sessions 4. Robert B. Aderholt 5. Robert E. ‘‘Bud’’ Cramer, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES 6. Spencer Bachus [Democrats 2, Republicans 5] 7. Artur Davis 1. Jo Bonner ALASKA SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE Ted Stevens [Republican 1] Lisa Murkowski At Large - Don Young ARIZONA SENATORS 2. Trent Franks John McCain 3. John B. Shadegg Jon Kyl 4. Ed Pastor 5. Harry E. Mitchell REPRESENTATIVES 6. Jeff Flake [Democrats 4, Republicans 4] 7. Rau´l M. Grijalva 1. Rick Renzi 8. Gabrielle Giffords ARKANSAS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES Blanche L. Lincoln [Democrats 3, Republicans 1] Mark L. Pryor 1. Marion Berry 2. Vic Snyder 3. John Boozman 4. Mike Ross CALIFORNIA SENATORS 2. Wally Herger Dianne Feinstein 3. Daniel E. Lungren Barbara Boxer 4. John T. Doolittle 5. Doris O. Matsui REPRESENTATIVES 6. Lynn C. Woolsey [Democrats 33, Republicans 19] 7. George Miller 1. Mike Thompson 8. Nancy Pelosi 295 296 Congressional Directory 9. Barbara Lee 32. Hilda L. Solis 10. Ellen O. Tauscher 33. Diane E. Watson 11. Jerry McNerney 34. Lucille Roybal-Allard 12. Tom Lantos 35. Maxine Waters 13. Fortney Pete Stark 36. Jane Harman 14. Anna G. Eshoo 37. —— 1 15. Michael M. Honda 38. Grace F. Napolitano 16. Zoe Lofgren 39. Linda T. Sa´nchez 17. Sam Farr 40. Edward R. Royce 18. Dennis A. Cardoza 41. Jerry Lewis George Radanovich 19. -

Anouncement from the Florida Developmental Disabilities Council

Anouncement from the Florida Developmental Disabilities Council Congressional Action Critical to Avoid Cuts to Developmental Disability Home and Community Based Waiver The Florida House has passed their Appropriations Act. There were no new budget changes for services. The cuts that remain in the House are a cap of $120,000 on Tier One cost plans and the elimination of behavior assistance services in group homes. The Florida Senate also passed their Appropriations Act. Sen. Peaden sponsored an amendment that had passed in the full Appropriations Committee to restore most of the cuts to the Agency for Persons with Disabilities (APD) if the enhanced Medicaid extension dollars - Federal Medical Assistance Percentages (FMAP) - come from the federal government. If the Federal Medicaid Match dollars are authorized there will be no cuts to dollars for consumer cost plans, APD providers and Intermediate Care facilities. The Senate shares the $120,000 cap to Tier One and the behavioral assistance cuts to group homes that the House has in their budget. Because these issues are the same in the House and the Senate, they will not be looked at again in the Budget Conference meetings. The Budget Conference process is a process of negotiating budget item differences from the House and the Senate. Our attention now turns to Congress. The U.S. House of Representatives has been preoccupied with health care reform and does not yet have a date on when they will address the FMAP issue. A jobs bill that includes the enhanced FMAP recently passed the Senate and now must be taken up by the House. -

Congressional Advisory Boards, Commissions, and Groups

CONGRESSIONAL ADVISORY BOARDS, COMMISSIONS, AND GROUPS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE ACADEMY BOARD OF VISITORS [Title 10, U.S.C., Section 9355(a)] Board Member Year Appointed Appointed by the President: Roel Campos 2016 Linda Cubero 2016 Benjamin Drew 2016 Judith Fedder 2016 Soudarak Hoppin 2016 Edward Rice (Chair) 2016 Appointed by the Vice President or the Senate President Pro Tempore: Senator Mazie K. Hirono, of Hawaii 2015 Senator Jerry Moran, of Kansas 2015 Senator Tom Udall, of New Mexico 2015 Appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives: Representative Jared Polis, of Colorado 2010 Representative Doug Lamborn, of Colorado 2009 Representative Martha McSally, of Arizona 2015 Bruce Swezey 2017 Appointed by the Chairman, Senate Armed Services Committee: Senator Cory Gardner, of Colorado 2015 Appointed by the Chairman, House Armed Services Committee: Vacant. UNITED STATES MILITARY ACADEMY BOARD OF VISITORS [Title 10, U.S.C., Section 4355(a)] Members of Congress Senate Richard Burr, of North Carolina. Kirsten E. Gillibrand, of New York. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. Christopher Murphy, of Connecticut. House Steve Womack, Representative of Arkansas, Sean Patrick Maloney, Representative of New Chair. York. K. Michael Conaway, Representative of Texas. Stephanie N. Murphy, Representative of Thomas J. Rooney, Representative of Florida. Florida. Presidential Appointees: Brenda Sue Fulton, of New Jersey, Vice Chair. 501 502 Congressional Directory Elizabeth McNally, of New York. Frederick H. Black, Sr., of North Carolina. Bridget Altenburg, of Illinois. Hon. Gerald McGowan, of Washington, DC. Jane Holl Lute, of Virginia. UNITED STATES NAVAL ACADEMY BOARD OF VISITORS [Title 10, U.S.C., Section 6968(a)] Appointed by the President: Judge Evan Wallach, U.S. -

9 Distribution List of Environmental Impact Statement

FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT SPRINGDALE NORTHERN BYPASS 9 DISTRIBUTION LIST OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Copies of the Final Environmental Impact Statement have been distributed to the following agencies and organizations: FEDERAL AGENCIES U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Little Rock District Permits Branch - Little Rock, AR U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service - Conway, AR U.S. Department of Interior, Office of Environmental Policy & Compliance- Washington, D.C. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency -Washington, D.C. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 6-Dallas, TX National Resources Conservation Service-Little Rock, AR STATE AGENCIES Arkansas Department of Health Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality Arkansas Department of Higher Education Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism Arkansas Economic Development Commission Arkansas Forestry Commission Arkansas Game & Fish Commission Arkansas Geological Commission Arkansas Land Commissioner Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission Arkansas Soil & Water Conservation Commission Arkansas State Plant Board Arkansas State Police Arkansas Water Resources Center Arkansas Waterways Commission Department of Arkansas Heritage Department of Education Department of Human Services Department of Finance & Administration Livestock & Poultry Commission Office of Rural Advocacy Office of the State Archeologist Office of the Governor State Historic Preservation Program DISTRIBUTION LIST OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT 9-1 FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT SPRINGDALE -

Talk Business Poll Conducted by Talk Business Research & Hendrix

Talk Business Poll Conducted by Talk Business Research & Hendrix College Thursday, October 14, 2010 AR-Governor & Senator 1,953 Likely Arkansas Voters Margin of Error +/- 2.2% How likely are you to vote in the November elections for statewide office? 94% Very Likely 6% Somewhat Likely N/A Somewhat Unlikely (Call Ended) N/A Very Unlikely (Call Ended) If the election for Arkansas Governor were today, who would you vote for? 34% Jim Keet, the Republican 3.5% Jim Lendall, the Green Party nominee 50% Governor Mike Beebe, the Democrat 12.5% Undecided If the election for U.S. Senate were today, who would you vote for? 4% John Gray, the Green Party nominee 36% Senator Blanche Lincoln, the Democrat 49% Cong. John Boozman, the Republican 4% Trevor Drown, the Independent 7% Undecided Q. For Statistical Purposes, please tell us your age. Q. Please tell us which ethnicity best describes you. Q. Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, or other? Q. Please tell us your gender. Notes on Raw Data/Weighting: Age (weighted by 2008 Arkansas exit poll data) 17% Under the age of 30 27% Between the ages of 30 and 44 37% Between the Ages of 45 and 64 19% 65 or older Ethnicity (not weighted) 8.5% African-American 1.5% Asian-American 85% Caucasian or White 2% Latino 3% Other Party ID (not weighted) 27% Republican 36% Democrat 30% Independent 7% Other Gender (weighted by 2008 Arkansas exit poll data) 45% Male 55% Female Congressional District (weighted) 25% First; 25% Second; 25% Third; 25% Fourth BREAKOUT