Beautiful Martyrs but Also to Obscure and Aestheticize the Holocaust Itself

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wertheimer, Editor Imagining the Seth Farber an American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B

Imagining the American Jewish Community Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor For a complete list of books in the series, visit www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSAJ.html Jack Wertheimer, editor Imagining the Seth Farber An American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B. Murray Zimiles Gilded Lions and Soloveitchik and Boston’s Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to Maimonides School the Carousel Ava F. Kahn and Marc Dollinger, Marianne R. Sanua Be of Good editors California Jews Courage: The American Jewish Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe “How Committee, 1945–2006 Goodly Are Thy Tents”: Summer Hollace Ava Weiner and Kenneth D. Camps as Jewish Socializing Roseman, editors Lone Stars of Experiences David: The Jews of Texas Ori Z. Soltes Fixing the World: Jewish Jack Wertheimer, editor Family American Painters in the Twentieth Matters: Jewish Education in an Century Age of Choice Gary P. Zola, editor The Dynamics of American Jewish History: Jacob Edward S. Shapiro Crown Heights: Rader Marcus’s Essays on American Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Jewry Riot David Zurawik The Jews of Prime Time Kirsten Fermaglich American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares: Ranen Omer-Sherman, 2002 Diaspora Early Holocaust Consciousness and and Zionism in Jewish American Liberal America, 1957–1965 Literature: Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth Andrea Greenbaum, editor Jews of Ilana Abramovitch and Seán Galvin, South Florida editors, 2001 Jews of Brooklyn Sylvia Barack Fishman Double or Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed editors Women and American Marriage Judaism: Historical Perspectives George M. -

Tazria-Metzora Vol.30 No.31.Qxp Layout 1

21 April 2018 6 Iyar 5778 Shabbat ends London 8.58pm Jerusalem 7.50pm Volume 30 No. 31 Tazria-Metzora Artscroll p.608 | Haftarah p.1172 Hertz p.460 | Haftarah p.477 Soncino p.674 | Haftarah p.702 In loving memory of David Yochanan ben Moshe Chair of Elijah, Dermbach, Germany. Before 1768. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem "On the eight day, the flesh of his skin shall be circumcised" (Vayikra 12:3). 1 Sidrah Summary: Tazria-Metzora 1st Aliya (Kohen) – Vayikra 12:1-23 bundle – sprinkle its blood seven times on the After childbirth, a lady would wait several weeks metzora. The metzora would also bring three before bringing an elevation offering (olah) and a animal offerings and three meal offerings. sin offering (chatat). Question: What types of animals did the metzora God told Moshe and Aharon that someone whose bring as offerings? (14:10) Answer on bottom of skin appeared to indicate a particular type of skin page 6. disease (tzara’at) would have to show the blemish 5th Aliya (Chamishi) – 14:21-32 to a Kohen (see p.4 article). The Kohen would A metzora who could not afford three animal evaluate and decide if the affliction was clearly offerings could instead bring one animal offering, tzara’at, thus rendering the person impure (tameh). one meal offering and two birds. If the case was unclear, the Kohen would quarantine the person for seven days, after which the Kohen 6th Aliya (Shishi) – 14:33-15:15 would re-inspect the afflicted area and declare Tzara’at also affected houses. -

NP Distofattend-2014-15

DISTRICT_CD DISTRICT_NAME NONPUB_INST_CD NONPUB_INST_NAME 91‐223‐NP‐HalfK 91‐224‐NP‐FullK‐691‐225‐NP‐7‐12 Total NonPub 010100 ALBANY 010100115665 BLESSED SACRAMENT SCHOOL 0 112 31 143 010100 ALBANY 010100115671 MATER CHRISTI SCHOOL 0 145 40 185 010100 ALBANY 010100115684 ALL SAINTS' CATHOLIC ACADEMY 0 100 29 129 010100 ALBANY 010100115685 ACAD OF HOLY NAME‐LOWER 049049 010100 ALBANY 010100115724 ACAD OF HOLY NAMES‐UPPER 0 18 226 244 010100 ALBANY 010100118044 BISHOP MAGINN HIGH SCHOOL 0 0 139 139 010100 ALBANY 010100208496 MAIMONIDES HEBREW DAY SCHOOL 0 45 22 67 010100 ALBANY 010100996053 HARRIET TUBMAN DEMOCRATIC 0 0 18 18 010100 ALBANY 010100996179 CASTLE ISLAND BILINGUAL MONT 0 4 0 4 010100 ALBANY 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) 0 230 572 802 010100 ALBANY 010100997616 FREE SCHOOL 0 25 7 32 010100 Total ALBANY 1812 010201 BERNE KNOX 010201805052 HELDERBERG CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 1 25 8 34 010201 Total 0 34 010306 BETHLEHEM 010306115761 ST THOMAS THE APOSTLE SCHOOL 0 148 48 196 010306 BETHLEHEM 010306809859 MT MORIAH ACADEMY 0 11 20 31 010306 BETHLEHEM 010306999575 BETHLEHEM CHILDRENS SCHOOL 1 12 3 16 010306 Total 0 243 010500 COHOES 010500996017 ALBANY MONTESSORI EDUCATION 0202 010500 Total 0 2 010601 SOUTH COLONIE 010601115674 CHRISTIAN BROTHERS ACADEMY 0 38 407 445 010601 SOUTH COLONIE 010601216559 HEBREW ACAD‐CAPITAL DISTRICT 0 63 15 78 010601 SOUTH COLONIE 010601315801 OUR SAVIOR'S LUTHERAN SCHOOL 9 76 11 96 010601 SOUTH COLONIE 010601629639 AN NUR ISLAMIC SCHOOL 0 92 23 115 010601 Total 0 734 010623 NORTH COLONIE CSD 010623115655 -

Association for Jewish Studies 43Rd Annual Conference December 18–20, 2011

43 ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES JEWISH FOR ASSOCIATION New York, NY 10011-6301 NY York, New 16th Street 15 West History Jewish for c/o Center Studies Jewish for Association 43ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES DECEMBER 18–20, 2011 GRAND HYATT WASHINGTON WASHINGTON, DC 43 RD ANNUAL CONFERENCE RD ANNUAL DECEMBER 18–20, 2011 Association for Jewish Studies Association for Jewish Studies c/o Center for Jewish History 43rd Annual Conference 15 West 16th Street New York, NY 10011-6301 Program Book Contents Phone: (917) 606-8249 Fax: (917) 606-8222 E-mail: [email protected] Association for Jewish Studies Goals and Standards.................................................... 4 www.ajsnet.org Institutional Members.................................................................................................... 5 President AJS Staff Marsha Rozenblit, University of Maryland Rona Sheramy, Executive Director Message from the Conference Chair............................................................................. 6 Vice President/Membership Karen Terry, Program and Membership and Outreach Coordinator Conference Information................................................................................................ 8 Anita Norich, University of Michigan Natasha Perlis, Project Manager Vice President/Program Emma Barker, Conference and Program Program Committee and Division Coordinators........................................................... 9 Derek Penslar, University of Toronto Associate 2011 Award Recipients................................................................................................. -

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California

ALABAMA ARKANSAS N. E. Miles Jewish Day School Hebrew Academy of Arkansas 4000 Montclair Road 11905 Fairview Road Birmingham, AL 35213 Little Rock, AR 72212 ARIZONA CALIFORNIA East Valley JCC Day School Abraham Joshua Heschel 908 N Alma School Road Day School Chandler, AZ 85224 17701 Devonshire Street Northridge, CA 91325 Pardes Jewish Day School 3916 East Paradise Lane Adat Ari El Day School Phoenix, AZ 85032 12020 Burbank Blvd. Valley Village, CA 91607 Phoenix Hebrew Academy 515 East Bethany Home Road Bais Chaya Mushka Phoenix, AZ 85012 9051 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 Shalom Montessori at McCormick Ranch Bais Menachem Yeshiva 7300 N. Via Paseo del Sur Day School Scottsdale, AZ 85258 834 28th Avenue San Francisco, CA 94121 Shearim Torah High School for Girls Bais Yaakov School for Girls 6516 N. Seventh Street, #105 7353 Beverly Blvd. Phoenix, AZ 85014 Los Angeles, CA 90035 Torah Day School of Phoenix Beth Hillel Day School 1118 Glendale Avenue 12326 Riverside Drive Phoenix, AZ 85021 Valley Village, CA 91607 Tucson Hebrew Academy Bnos Devorah High School 3888 East River Road 461 North La Brea Avenue Tucson, AZ 85718 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Yeshiva High School of Arizona Bnos Esther 727 East Glendale Avenue 116 N. LaBrea Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85020 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Participating Schools in the 2013-2014 U.S. Census of Jewish Day Schools Brandeis Hillel Day School Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy 655 Brotherhood Way 9120 West Olympic Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94132 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Brawerman Elementary Schools Hebrew Academy of Wilshire Blvd. Temple 14401 Willow Lane 11661 W. -

The Jewish Observer

··~1 .··· ."SH El ROT LEUMI''-/ · .·_ . .. · / ..· .:..· 'fo "ABSORPTION" •. · . > . .· .. ·· . NATIONALSERVICE ~ ~. · OF SOVIET. · ••.· . ))%, .. .. .. · . FOR WOMEN . < ::_:··_---~ ...... · :~ ;,·:···~ i/:.)\\.·:: .· SECOND LOOKS: · · THE BATil.E · . >) .·: UNAUTHORIZED · ·· ·~·· "- .. OVER CONTROL AUTOPSIES · · · OF THE RABBlNATE . THE JEWISH OBSERVER in this issue ... DISPLACED GLORY, Nissan Wo/pin ............................................................ 3 "'rELL ME, RABBI BUTRASHVILLI .. ,"Dov Goldstein, trans lation by Mirian1 Margoshes 5 So~rn THOUGHTS FROM THE ROSHEI YESHIVA 8 THE RABBINATE AT BAY, David Meyers................................................ 10 VOLUNTARY SERVICE FOR WOMEN: COMPROMISE OF A NATION'S PURITY, Ezriel Toshavi ..... 19 SECOND LOOKS RESIGNATION REQUESTED ............................................................... 25 THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July and August, by the Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, New York 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. Subscription: $5.00 per year; Two years, $8.50; Three years, $12.00; outside of the United States, $6.00 per year. Single copy, fifty cents. SPECIAL OFFER! Printed in the U.S.A. RABBI N ISSON W OLPJN THE JEWISH OBSERVER Editor 5 Beekman Street 7 New York, N. Y. 10038 Editorial Board D NEW SUBSCRIPTION: $5 - 1 year of J.O. DR. ERNEST L. BODENHEIMER Plus $3 • GaHery of Portraits of Gedolei Yisroel: FREE! Chairman RABBI NATHAN BULMAN D RENEWAL: $12 for 3 years of J.0. RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS Plus $3 - Gallery of Portraits of Gedo lei Yisroel: FREE! JOSEPH FRIEDENSON D GIFT: $5 - 1 year; $8.50, 2 yrs.; $12, 3 yrs. of ].0. RABBI YAACOV JACOBS Plus $3 ·Gallery of Portraits of Gedolei Yisroel: FREE! RABBI MOSHE SHERER Send '/Jf agazine to: Send Portraits to: THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not iVarne .... -

Bus Operator Profiles 2018

OPERATOR PROFILE April 1, 2018 - March 31, 2019 Total Number Number of Percent OPERATOR NAME of Inspections Out of Service Out of Service OPER-ID Location Region 1ST CLASS TRANSPORTATION SERVICE 1 0 0 48486 QUEENS VILLAGE 11 21ST AVENUE BUS CORP 131 10 7.6 3531 BROOKLYN 11 21ST AVENUE BUS CORP(BX) 2 0 0 58671 BRONX 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 33 1 3 6043 BROOKLYN 11 5 STAR LIMO OF ELMIRA 2 0 0 49862 ELMIRA 4 5 STAR SCHOOL BUS LLC 47 1 2.1 55223 BROOKLYN 11 A & A AFFORDABLE LIMOUSINE SERV INC 2 0 0 55963 BETHPAGE 10 A & B VAN SERVICE 48 0 0 3479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & N TRANSIT CORP. 12 0 0 51985 BROOKLYN 11 A & W TOURS INC 6 0 0 46192 BROOKLYN 11 A + MEDICAL TRANSPORTATION 1 1 100 58635 BALDWINSVILLE 3 A AND M QUALITY LIMO INC 2 0 0 57446 JERSEY CITY NJ 11 A HUDSON VALLEY LIMOUSINE INC 3 0 0 49975 CIRCLEVILLE 8 A TO B EXPRESS TRANS INC 16 0 0 33830 ISLANDIA 10 A WHITE STAR LIMOUSINE SERVICE, INC 12 4 33.3 48165 NEW HYDE PARK 11 A YANKEE LINE INC 3 0 0 49754 BOSTON MA 11 A&D TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 27 0 0 55234 ONEONTA 2 A&H AMERICAN LIMO CORP. 10 3 30 53971 AVENEL NJ 11 A&H LIMO CORP 3 1 33.3 58529 RUTHERFORD NJ 11 A&H NYC LIMO CORP. 8 2 25 56633 RUTHERFORD NJ 11 A.E. FALCONI CORP. 2 0 0 25675 CORONA 11 A.E.F. -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

In Only 2 Weeks

JOAN DACHS BAIS YAAKOV • YESHIVAS TIFERES TZVI 6122 N. CALIFORNIA AVENUE • 773.465.8889 • JDBYYTT.ORG NEW STUDENT APPLICATION DEADLINE: IN ONLY 2 WEEKS Rabbi Borenstein’s class learning about the שר האופים and שר המשקים dreams of ב׳ שבט תשפ״א • JAN. 15 2021 הדלקת נרות 4:24 פרשת וארא CALENDAR UPDATE לע”נ Tuesday’s learning in JDBY and YTT was sponsored - MON. JAN. 18 ברוך בן אברהם עביר ז”ל JDBY-YTT Midwinter Break SUN. JAN 24 לע”נ Tuesday’s learning in YTT was sponsored משה מאיר בן הרב יוסף ז”ל by Tzvi and Sharona Perlman and Family MON. JAN. 25 School Resumes for JDBY-YTT Friday’s learning in JDBY and YTT was dedicated in memory of our beloved talmidah ATT Professional Development Day – YTT Dismissal 12:15; MON. FEB. 15 ע”ה Miss Sara Leah Kacev Nursery No School שרה לאה ע”ה בת יבלח”ט ר’ יוסף נ”י ג’ שבט whose yahrtzeit is on Shabbos Affiliated with the Associated Talmud Torahs of Chicago. A partner with the Jewish United Fund in serving our community. Rabbi Pfeiffer’s Class Using A Speaker To Learn B’chavrusa With Boys Who Are In Quarantine CHAIM DAFNER WITH HIS KRIAH KUPCAKE! FROG HATS FOR LETTER F RABBI KAUFMAN’S CLASS ACTING LEARNING ABOUT THE OUT THE PARSHA LAMED TES MELACHOS 2 STAR TALMID Eli Saks proudly showing his completed Tefilla card from Rabbi Kaufman and a Nachas Note for Rabbi TIFERES TALMIDIM Katz. MICHAEL ABOWITZ, YOSEF AHRON KALISH, ARYEH GORDON SHMUEL PARETZKY, ELI SHULMAN, GEDALYA BROYDE SPECIAL SIYUM Dovi Cohen and Yechiel Sheinfeld completed Meseches Yuma baal peh-in one shot! Efraim Diena said a Dvar Torah in honor of the Siyum and Rabbi Muller and Rabbi Tenenbaum joined the class in celebrating this accomplishment. -

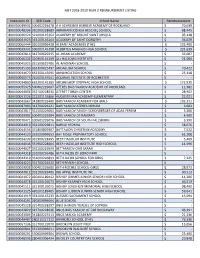

MST 2018-2019 Year 2 Reimbursement Listing

MST 2018-2019 YEAR 2 REIMBURSMENT LISTING Institution ID SED Code School Name Reimbursement 800000039032 500402226478 A H SCHREIBER HEBREW ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 70,039 800000048206 310200228689 ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL SCHOOL $ 68,445 800000046124 321000145364 ACADEMY OF MOUNT SAINT URSULA $ 95,148 800000041923 353100145263 ACADEMY OF SAINT DOROTHY $ 36,029 800000060444 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) $ 102,490 800000039341 500101145198 ALBERTUS MAGNUS HIGH SCHOOL $ 231,639 800000042814 342700629235 AL-IHSAN ACADEMY $ 33,087 800000046332 320900145199 ALL HALLOWS INSTITUTE $ 21,084 800000045025 331500629786 AL-MADINAH SCHOOL $ - 800000035193 662300625497 ANDALUSIA SCHOOL $ 70,422 800000034670 662300145095 ANNUNCIATION SCHOOL $ 25,148 800000050573 261600167041 AQUINAS INSTITUTE OF ROCHESTER $ - 800000034860 662200145185 ARCHBISHOP STEPINAC HIGH SCHOOL $ 172,930 800000055925 500402229697 ATERES BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 12,382 800000044056 332100228530 ATERET TORAH CENTER $ 28,962 800000051126 222201155866 AUGUSTINIAN ACADEMY-ELEMENTARY $ 22,021 800000042667 342800226480 BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY FOR GIRLS $ 103,321 800000087003 342700226221 BAIS YAAKOV ATERES MIRIAM $ 3,683 800000043817 331500229003 BAIS YAAKOV FAIGEH SCHONBERGER OF ADAS YEREIM $ 5,306 800000039002 500401229384 BAIS YAAKOV OF RAMAPO $ 4,980 800000070471 590501226076 BAIS YAAKOV OF SOUTH FALLSBURG $ 3,390 800000044016 332100229811 BARKAI YESHIVA $ 58,076 800000044556 331800809307 BATTALION CHRISTIAN ACADEMY $ 7,522 800000044120 332000999653 BAY RIDGE PREPARATORY SCHOOL -

Luach for Week of Ki Tisa Chabad NP

Baruch Hashem! Luach for Week of Ki Tisa www.chabadnp.com Chabad NP - 21-28 Adar 5781 / March 5-12 Friday, 21 Adar ● Shabbat Candle Lighting at 5:49 PM ● Kabbalat Shabbat - (P. 154) ● Kiddush on p. 179 ● Today in Jewish History R. Elimelech of Lizhensk (1786) The great Rabbi Elimelech of Lizhensk (1717-1786) was one of the elite disciples of Rabbi DovBer, the Maggid of Mezritch, and a colleague of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi. He is also widely known as the No'am Elimelech, the title of the renowned chassidic work he authored. Rabbi Elimelech attracted many thousands of chassidim, among them many who after his passing became great chassidic masters in their own right. Most notable amongst them was Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak Horowitz, the "Seer of Lublin." Many of the current chassidic dynasties trace themselves back to Rabbi Elimelech. 22 Adar - Shabbat Ki Tisa ● Torah Reading Ki Tisa: Exodus 30:11 - 34:35 Parshat Parah: Numbers 19:1-22 Parah: Ezekiel 36:16-36 ● Laws and Customs Parshat Parah The Torah reading of Parah is added to the weekly reading. Parah details the laws of the "Red Heifer" and the process by which a person rendered ritually impure by contact with a dead body was purified. (When the Holy Temple stood in Jerusalem, every Jew had to be in a state of ritual purity in time for the bringing of the Passover offering in the Temple. Today, though we're unable to fulfill the Temple-related rituals in practice, we fulfill them spiritually by studying their laws in the Torah. -

Shabbat Shemot

Candle Lighting W E L C O M E T O T H E D A T M I N Y A N ! (earliest) 3:53 pm (latest) 4:35 pm SHABBAT SHEMOT January 9, 2021 // 25 Tevet 5781 Havdalah 5:38 pm Bara Loewenthal and Nathan Rabinovitch, Co- Presidents D'var Torah by Rabbi Sacks zt"l We invite men and women to use the link in the Rabbi Sacks z’’l had prepared a full year of Covenant & Conversation for 5781, accompanying email to sign up for our in person based on his book Lessons in Leadership. The Office of Rabbi Sacks will carry on minyanim, located at The Jewish Experience. For distributing these essays each week, so people around the world can continue to those unable to make it, we encourage everyone to join us for our virtual daily davening and learn and be inspired by his Torah. learning opportunities. This week’s parsha could be entitled “The Birth of a Leader.” We see Moses, All davening times and classes are published on adopted by Pharaoh’s daughter, growing up as a prince of Egypt. We see him as a our website and calendar. We currently are not young man, for the first time realising the implications of his true identity. He is, offering a virtual option for Shabbat davening. and knows he is, a member of an enslaved and suffering people: “Growing up, he went out to where his own people were and watched them at their hard labour. TJE Minyan Times: He saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, one of his own people” (Ex.