MUSHTAQ AHMAD MALLA Sr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page-7 Local.Qxd

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU TUESDAY, DECEMBER 29, 2020 (PAGE 7) Home Minister unveils Arun Centre invites 40 farmer Jaitley’s statue at DDCA premises unions for talks on Dec 30 NEW DELHI, Dec 28: BCCI President and former though the DDCA has been in India captain Sourav Ganguly, "turmoil" for some time. NEW DELHI, Dec 28: realise the truth. Tomar also said agenda for fresh talks, but despite A controversial build-up he is hopeful of an early solution to this, the government in letter today India opener Shikhar Dhawan, ex "When we play and get 100, The Centre on Monday invited notwithstanding, the Delhi and India opener Gautam Gambhir, it gets recognition but lot of peo- the impasse. has not mentioned any specific District Cricket Association 40 protesting farmer unions for the In a letter to the farmer unions, agenda," Kohar today. who is also a BJP MP from Delhi, ple work behind the scenes and next round of talks on December (DDCA) today unveiled the stat- BCCI Vice President Rajeev help the cricketers. He was a Agriculture Secretary Sanjay "But, we have agreed in-prin- ue of its former president Arun 30 on all relevant issues to find a Aggarwal invited them for the ciple to hold talks with the govern- Shukla and Union Minister cricketer's person. That is the "logical solution" with "open Jaitley at its premises in the Hardeep Puri attended the unveil- role of an administrator," he said. talks at 2 pm on Wednesday at ment." memory of the late administrator mind" to the prolonged impasse Vigyan Bhavan in the national The All India Kisan Sangharsh ing ceremony along with a num- "I remember a phone call over the three new agri laws. -

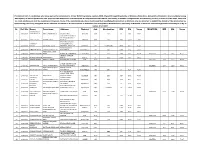

Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. MM MO Acad.%Age 1 20600614 YASMEENA AHAD KH

General Merit list of candidates who have applied for admission to MA Education Progamme (Distance Mode) session-2020 Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. MM MO Acad.%age 1 20600614 YASMEENA AHAD KH. ABDUL AHAD WANI NAMBLABAL PAMPORE PULWAMA OM 10 8.4 84.00 2 20601519 MEHFOOZA ASHIQ ASHIQ HUSSAIN MIR CHADOORA BUDGAM OM 1000 835 83.50 3 20600464 IQRA GULAM MOHD QASBA NUND RESHI COLONY A BEMINA SRINAGAR OM 100 82 82.00 4 20600013 RASIK AHMAD RESHI GUL MOHD RESHI GUNDINOWROZE ANANTNAG OM 945 770 81.48 5 20601399 MUDASIR AHMAD HAJAM BASHIR AHMAD HAJAM BAKUR ALASTENG GANDERBAL GANDERBAL WUP 1000 811 81.10 BABAPORA, BABADEMB ROAD, 6 20602361 SOHAN CHOUDHARY BHOLA RAM CHOUDHARY SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM 1000 809 80.90 7 20602039 MUSTAFA MAJEED AB MAJEED SHAH HAJI BAGH HMT BUDGAM BUDGAM OM 1000 808 80.80 8 20600861 ABID HUSSAIN HAJI MOHD AMIN HAJI SEDOW SHOPIAN SHOPIAN RBA 1000 806 80.60 9 20600983 ASIMA MANZOOR GANIE MANZOOR AHMAD GANIE CHANDHARA PAMPORE PULWAMA PULWAMA OM 100 80.4 80.40 PHASE-II, ALAMDAR BASTI, CHARAR-- 10 20601853 UMAR YOUSEF MOHD YOUSEF KHIRKA SHARIEF BUDGAM OM 10 8 80.00 11 20600127 ARSHID AHMAD MIR GHULAM MOHAMMAD MIR KANITAR SEDRABAL SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM 10 7.98 79.80 12 20601369 INSHA GUL GULAM MOHAMMAD BHAT SHAH HAMDAN COLONY NAIK BAGH SRINAGAR OM 10 7.93 79.30 13 20600164 RUKHSANA MOHAMMAD HAFIZ DAR ZADIBAL HAWAL SRINAGAR OM 10 7.91 79.10 14 20601935 AASHAQ HUSSAIN WANI MOHD ABDULLAH WANI GUNDI SHAMASH BUDGAM RBA 1000 789 78.90 15 20600062 MASARAT NABI BADANA GH NABI BADANA ZAKURA HAZRATBAL SRINAGAR CGB 1000 782 78.20 NUNDRESHI COLONY BEMINA 16 20601409 SADAF ZAHOOR ZAHOOR AHMAD KHAN SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM 330 258 78.18 17 20601556 NIDA BASHIR BASHIR AHMAD ZADOO HOUSE NO 141 BEMINA BYPASS SRINAGAR OM 10 7.79 77.90 H.NO. -

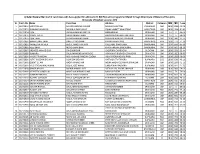

Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO

Modified General Merit list of candidates who have applied for admission to B.Ed. prgoramme (Kashmir Chapter) offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir session-2018 Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %age 1 1892469 TABASUM GANI ABDUL GANI GANAIE NAZNEENPORA TRAL PULWAMA OM 1170 1009 86.24 2 1898382 ZARKA AMIN M A PAMPORI BAGH-I-MEHTAB SRINAGAR OM 10 8.54 85.40 3 1891053 MAIDA MANZOOR MANZOOR AHMAD DAR BATENGOO KHANABAL ANANTNAG ANANTNAG OM 500 426 85.20 4 1892123 FARHEENA IFTIKHAR IFTIKHAR AHMAD WANI AKINGAM ANANTNAG ANANTNAG OM 1000 852 85.20 5 1891969 PAKEEZA RASHID ABDUL RASHID WANI SOGAM LOLAB KUPWARA OM 10 8.51 85.10 6 1893162 SADAF FAYAZ FAYAZ AHMAD SOFAL SHIRPORA ANANTNAG OM 100 85 85.00 BASRAH COLONY ELLAHIBAGH 7 1895017 ROSHIBA RASHID ABDUL RASHID NAQASH BUCHPORA SRINAGAR OM 10 8.47 84.70 8 1894448 RUQAYA ISMAIL MOHAMMAD ISMAIL BHAT GANGI PORA, B.K PORA, BADGAM BUDGAM OM 10 8.44 84.40 9 1893384 SHAFIA SHOWKET SHOWKET AHMAD SHAH BATAMALOO SRINAGAR OM 10 8.42 84.20 BABA NUNIE GANIE, 10 1893866 SAHREEN NIYAZ MUNSHI NIYAZ AHMAD KALASHPORA,SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM 900 756 84.00 11 1893858 UZMA ALTAF MOHD ALTAF MISGAR GULSHANABAD K.P ROAD ANANTNAG ANANTNAG OM 1000 837 83.70 12 1893540 ASMA RAMZAN BHAT MOHMAD RAMZAN BHAT NAGBAL GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM 3150 2630 83.49 13 1895633 SEERATH MUSHTAQ MUSHTAQ AHMED WANI DEEWAN COLONY ISHBER NISHAT SRINAGAR OM 1900 1586 83.47 14 1891869 SANYAM VIPIN SETHI ST.1 FRIENDS ENCLAVE FAZILKA OTHER STATE OSJ 2000 1666 83.30 15 1895096 NADIYA AHAD ABDUL AHAD LONE SOGAM LOLAB KUPWARA OM 10 8.33 83.30 16 1892438 TABASUM ASHRAF MOHD. -

Kupwara District

Ground Water Information Booklet- Kupwara District Government of India Ministry of Water Resources CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET KUPWARA DISTRICT, JAMMU & KASHMIR NORTH WESTERN HIMALAYAN REGION JAMMU March 2013 Ground Water Information Booklet- Kupwara District GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET KUPWARA DISTRICT, JAMMU & KASHMIR CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 CLIMATE & RAINFALL 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOIL TYPES 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO 4.1 Geology 4.2 Hydrogeology 4.3 Depth to water level 4.4 Ground Water Resources 4.5 Ground Water Quality 4.6 Status of Ground Water Development 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 5.1 Ground Water Development 5.2 Water Conservation & Artificial Recharge 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES & PROBLEMS 7.0 AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY 8.0 AREAS NOTIFIED BY CGWA / SGWA 9.0 RECOMMENDATIONS Ground Water Information Booklet- Kupwara District KUPWARA DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl. No. ITEMS STATISTICS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i) Geographical area (sq km) 2379 ii) Administrative Divisions (2001) • Number of Tehsil & Sub-tehsils 3 • Number of CD Blocks 11 • Number of Panchayats 234 • Number of Villages 370 iii) Population (2001 Census) • Total population 6,50,393 persons • Population Density (pers/sq km) 237 • Muslim & others Population 97.37% & 2.63% • Sex Ratio 906 iv) Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 869 mm 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic units • High Karewa Plateau lands • Sharp ridges of hard rock • Intervening valleys & River Terraces- Lolab valleys that is 6 Kms long and 4.4 kms wide is most important. Average Range 1635 m amsl Major Drainages • Kishan Ganga basin • Pohru river is the distributaries of Jhelum • Nanchar Nala drains Eastern part • Pohru river basin • Kahmil Nala drains Western part 3. -

Provisional List of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to 2

Provisional List of candidates who have applied for admission to 2-Year B.Ed.Programme session-2020 offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir. Any candidate having discrepancy in his/her particulars can approach the Directorate of Admissions & Competitive Examinations, University of Kashmir alongwith the documentary proof by or before 31-07-2021, after that no claim whatsoever shall be considered. However, those of the candidates who have mentioned their Qualifying Examination as Masters only are directed to submit the details of the Graduation by approaching personally alongwith all the relevant documnts to the Directorate of Admission and Competitive Examinaitons, University of Kashmir or email to [email protected] by or before 31-07-2021 Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO %age MASTERS MM MO %age SHARIQ RAUOF 1 20610004 AHMAD MALIK ABDUL AHAD MALIK QASBA KHULL KULGAM RBA BSC 10 6.08 60.80 VPO HOTTAR TEHSILE BILLAWAR DISTRICT 2 20610005 SAHIL SINGH BISHAN SINGH KATHUA KATHUA RBA BSC 3600 2119 58.86 BAGHDAD COLONY, TANZEELA DAWOOD BRIDGE, 3 20610006 RASSOL GH RASSOL LONE KHANYAR, SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM BCOMHONS 2400 1567 65.29 KHAWAJA BAGH 4 20610008 ISHRAT FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMAD DAR BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM BSC 1800 912 50.67 MOHAMMAD SHAFI 5 20610009 ARJUMAND JOHN WANI PANDACH GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM BSC 1800 899 49.94 MASTERS 700 581 83.00 SHAKAR CHINTAN 6 20610010 KHADIM HUSSAIN MOHD MUSSA KARGIL KARGIL ST BSC 1650 939 56.91 7 20610011 TSERING DISKIT TSERING MORUP -

Census of India 1981

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES-8 JAMMU & KASHMIR Special Paper of 1981 VILLAGE / TOWN WISE POPULATION AND SCHEDULED CASTE POPULATION ABDUL GANI Joint Dil ector of Census Operations Jammu and Kashmir PREFACE This is a special publication presenting the 1981 Census total popu lation and scheduled caste population of the State, districts and Tehsils down to village/urban block level to meet the requirement of data users interested in figures of population at village/ward level. This requirement could have been served by the 1981 District Census Handbooks which contain comprehensive basic information about populatIon by sex including literacy and work partici pation but the printing and publication of these handbooks which is the respon sibility of the State government will take some time. Until these handbooks are published, it is hoped that the present volume will serve a useful purpose to feed the urgent requirement of all data users. The Director of Census Opserations Shri A. H. Khan, under whose guidance the entire census operations were carried out, deserve all cred it for the success of the operations but he had to leave the organisation because of superannuation before this paper could be made ready for the press. I must record my deepest sense of gratitude to Shri V.S. Verma, Registrar General, India and Shri V.P. Pandey, Joint Registrar General, IndIa for their valuable guidance and for having agreed to bring out this specIal paper even in deviation of the approved census publications programme and arrange for its printing on a priority basis through the Printing Divi~ion of the Registrar General's Office under the supervision of Shri Tirath Dass, Joint Director. -

December, 2019)

IMPLEMENTATION AND ALLOCATION OF BAR CODES TO HEALTH CARE FACILITIES IN JAMMU & KASHMIR PCB (December, 2019) Jammu & Kashmir Pollution Control Board Parivesh Bhawan, Gladni, Transport Nagar, Narwal, Jammu-180 006 Sheikh-ul -Alam Complex, Behind Govt. Silk Factory, Rajbagh,Srinagar -190 0008 https://jkspcb.nic.in E.mail: [email protected] Government of Jammu & Kashmir JAMMU & KASHMIR POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD IMPLEMENTATION OF BAR CODE SYSTEM IN HEALTH CARE FACILITIES AND COMMON BIO-MEDICAL WASTE TREATMENT FACILITES OF JAMMU & KASHMIR The Bio-medical Waste Management Rules, 2016 notified on 28.03.2016 and amended thereof on 16/3/2018, 19/2/2019 and 10/5/2019, respectively, under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, stipulates that it is the duty of every Health Care Facility (HCF) to establish a Bar Code system for bags or containers containing biomedical waste (BMW) to be sent out of the premises for further treatment and disposal in accordance with the guidelines issued by the Central Pollution Control Board, by 27.03.2019 [Rule-4 (i)]. Also, Rule 5 of the BMWM Rules, 2016 stipulates that it is the duty of every Operator of a Common Bio-medical Waste Treatment Facility (CBMWTF) to establish bar code system for handling of bio-medical waste in accordance with the guidelines issued by the Central Pollution Control Board, by 27.03.2019. “Guidelines for Bar Code System for Effective Management of Bio-medical Waste” prepared by Central Pollution Control Board, Delhi in April, 2018, is to facilitate and provide guidance to both the Occupier as well as Operator of CBMWTF to establish bar code system and also to have uniformity in adoption of the bar code system throughout the country, thereby ensuring effective enforcement of the BMWM Rules, 2016. -

A Brief About HELP Foundation, J&K

A Brief about HELP Foundation, J&K HELP Foundation J&K is a nonprofit organization (registered as a society with the Registrar of Societies) set up in 1997, by Nighat Shafi, with the objective of providing a helping hand to people affected by the violence in the strife-torn valley. The focus has been on providing education and mental health counseling to women and children, who have been the worst victims of turmoil, relief and rehabilitation to various sections of the society who are severely challenged by physical disability and/or economic deprivation. With a team of dedicated trustees, volunteers and staff, the Foundation has extended its activities in almost all districts of Jammu and Kashmir State. EDUCATION, CAPACITY BUILDING & TRAININGS: SHAH ANWAR MEMORIAL SECONDARY SCHOOL: The school is located in an area which is close to the Line of Control (LOC) between India & Pakistan. This area was worst hit by violence which erupted in the valley in 1989. The district has the most number of widows. In 2000, the Foundation took possession of an existing primary school with only 24 children. The Foundation constructed an additional building with every kind of facility like, computer lab, library, science laboratory and a bus service to carry children from far flung areas of the district. A new class was added every year and the school has become a Secondary school, which is a leading school in the district of Kupwara. In the year 2007 another 3 storey building with 15 rooms was constructed with an attached play ground. At present, the school has enrolled 500 children with 250 orphans who are not charged any tuition fee and are also provided books and uniforms free of charges, also the families of the orphan children are provided regular financial assistance. -

Social Welfare Deptt

AADHAR BASED BIOMETRIC IDENTIFICATION AND SKILL PROFILING Reports Select Department :- SOCIAL WELFARE DE Select District :- All Sno. District Name Parentage Address Present Office DOB Category YASMEENA MOHD ANWAR DISTRICT SOCIAL WELFARE 1 ANANTNAG FOHAR MATTAN ANANTNAG 14-03-1977 CASUAL LABOURERS ANWAR BHAT DEPT ANANTNAG PART TIME SWEEPERS IN 2 ANANTNAG REHTI BEGUM GH MOHD WAGAY MATTAN ANNATNAG SW ANANTNAG 07-06-1962 DIFFERENT DEPARTMENTS MOHD PART TIME SWEEPERS IN 3 ANANTNAG RAMZAN MOHD SHABAN AINOO PAHALGAM SW ANANTNAG 06-03-1975 DIFFERENT SHEIKH DEPARTMENTS SHAHZADA FAROOQ AHMAD GULSHANABAD SARNAL DISTRICT SOCIAL WELFARE 4 ANANTNAG 12-03-1968 CASUAL LABOURERS AKTHER BHAT ANANTNAG DEPT ANANTNAG PART TIME SWEEPERS IN ABDUL GANI 5 ANANTNAG HAJRA AKHTER JANGLATMANDI ANANTNAG DSWO ANANTNAG 21-07-1963 DIFFERENT SHEIKH DEPARTMENTS DISTRICT SOCIAL WELFARE 6 ANANTNAG NUSRAT JAN ALI MOHD WAZA SRIGUFWAWA ANANTNAG 24-02-1983 CASUAL LABOURERS DEPT ANANTNAG FEHMEEDA PEER IFRAN MIRMADAN DOORU 7 ANANTNAG DOORU 30-03-1977 SEASONAL LABOURERS AHKTER AHMAD ANANTNAG DISTRICT SOCIAL WELFARE 8 ANANTNAG NIGHAT RASHID AB RASHID WANI HAZRATBAL ANANTNAG 27-06-1977 CASUAL LABOURERS DEPT ANANTNAG http://10.149.2.27/abbisp/AdminReport/District_Wise.aspx[1/17/2018 2:40:49 PM] SWEETY 9 ANANTNAG ALI MOHD WANI NAI BASTI KP ROAD DOORU 01-01-1965 SEASONAL LABOURERS AKHTER SHAHEENA 10 ANANTNAG AB AZIZ NAJAR MOMINABAD ANANTNAG DSWO ANANTNAG 27-11-1977 CASUAL LABOURERS AKHTER PART TIME SWEEPERS IN JASREENA 11 ANANTNAG ABDUL GANI MALIK MIR MAIDAN DOORU SW ANANTNAG 15-03-1994 -

Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address

Updated General Meri List of candidates who have applied for admission to MA Education programme offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir session-2018 Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %age 1 18272836 SABREENA ALI ALI MOHAMMAD KUMAR MONGHAMA TRAL PULWAMA OM 2400 1598 66.58 2 18272853 SUMMAYYA BASHIR BASHIR AHMAD BHAT IQBAL MARKET ANANTNAG ANANTNAG OM 2400 1964 81.83 3 18272854 IQRA GH MOHAMMAD SHOLLA HABBAKADAL SRINAGAR OM 10 6 60.00 4 18272856 KOMAL NAZIR NAZIR AHMAD SHAH BAGWANPORA BAR BAR SHAH SRINAGAR OM 10 6 60.00 5 18272859 IQRA SHAH ALI MOHAMMAD SHAH MAHARAJA BAZAR SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM 1800 940 52.22 6 18272861 SHAHID SIRAJ SHAH SIRAJ UD DIN SHAH KAMAD ANANTNAG ANANTNAG RBA 1000 773 77.30 7 18272881 YASMEENA AKTHER ABDUL AHAD TANTRAY GUZERBAL GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM 1000 658 65.80 8 18272882 ASEE SHAFI MOHD SHAFI BHAT KHAN HARRAN GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM 1000 682 68.20 9 18272887 ARSHEED AHMAD DAR GH QADIR DAR QAZIPORA CHADOORA BUDGAM OM 1800 998 55.44 10 18272889 SUMAIRA GHULAM MOHD WANGNOO ARAMWARI RAJBAGH SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM 1800 1023 56.83 11 18272890 MASRAT RAMZAN MOHAMMAD RAMZAN GOONA ABI KARPORA NEHRU PARK SRINAGAR OM 1800 1009 56.06 12 18272891 ALTAF HUSSAIN BADANA ALIM DIN BADANA HAFRADA TRATHPORA KUPWARA CGB 1800 830 46.11 13 18272892 QURAT UL AIN NAZIR AHMAD MIR INDRA NAGAR SONWAR SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM 1800 1100 61.11 14 18272893 MUSHTAQ AHMAD AWAN ABDUL AZIZ AWAN DARDPORA KRALPORA KUPWARA CGB 1800 931 51.72 15 18272898 SHAKIR BASHIR BASHIR AHMAD SOFI SATBONI LAL -

CHAPTER 1. 1.0 General Information About Lessee/Licensee A) Name & Address of the Lessee Mr

CHAPTER 1. 1.0 General information about lessee/Licensee a) Name & address of the lessee Mr. Ab. Ahad Wani S/O Mohd. Munawar Wani. R/O: Kalarooch A/P: Drugmulla Kupwar (J&K) Registered office: Kalarooch A/P: Drugmulla Kupwara (J&K) b) Status of the applicant Private Individual. c) Name & address of the RQP preparing the mining plan Gulam Nabi Chowdry, Abdul Majid Mir 05/DGM/RQP/2017 11/DGM/RQP/2017 9419086373, 9419458699 1.1 Details of the Mining Lease Letter of intent in favour of M/S Ab. Ahad Wani. S/O Mohd. Munawar Wani R/O Kalarooch A/P: Drugmulla Kupwar (J&K) has been issued by the Director Geology & Mining vide his communication No. 676/MCC/DGM/Block-09/Kup/18/6680-84 dated 04-01-2018 for grant of Mining lease of Minor mineral Block, Check Drugmula to Kalaruch Upstream Pohru Nallah District Kupwara covering an area 9.40 hectares (Including prohibited area). This Minor mineral block is located in Check Drugmula Tehsil & District Kupwara. Details of the minor mineral block with Khasra number is given below: Table-1 S.NO Village Name Khasra No. Type Hectares 1.0 Check ---- Nallah, Muck, 9.40 Drugmula Boulders, Bajri 1 a) Name of Mineral Minor Mineral including boulders, cobbles, pebbles, sand and Nallah muck is contained in the lease area. b) Description Report of the mining lease/ Quarry license with plan (enclose copy of sanction order/ lease deed/ license) Director Geology & Mining vide his communication No. 676/MCC/DGM/Block- 09/Kup/18/6680-84 dated 04-01-2018 (Annexure-I), issued letter of intent in favour of the successful bidder for submission of Mining Plan and Environment clearance within 6 months so that lease is granted in his favour for the Block Check Drugmula to Kalaruch Upstream Pohru Nallah District Kupwara covering an area 9.40 hectares. -

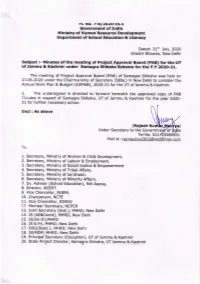

Minutes of the Meeting of Project Approval Board (PAB) for the UT of Jammu & Kashmir Under Samagra Shiksha Scheme for the F.Y 2O2O-2L

Fl. No. 7-Al2O2O-IS.4 Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education & Literacy Dated: 31't )uly,2O2O Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi Subject :- Minutes of the meeting of Project Approval Board (PAB) for the UT of Jammu & Kashmir under Samagra Shiksha Scheme for the F.Y 2O2O-2L. The meeting of Project Approval Board (PAB) of Samagra Shiksha was held on 23.06.2020 under the Chairmanship of Secretary (SE&L) in New Delhi to consider the Annual Work Plan & Budget (AWP&B), 202O-2t for the UT of Jammu & Kashmir. 2. The undersigned is directed to forward herewith the approved copy of PAB i.'iinutes in respect of Samagra Shiksha, UT of Jammu & Kashmir for the year 2O2O- 2L for fufther necessary action. Encl : As above (Rajesh Ku ) Under Secretary to the Governm ta Tel No. 011 3384501 Mail id : [email protected] To, 1. Secretary, Ministry of Women & Child Development. 2. Secretary, Ministry of Labour & Employment. 3. Secretary, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment 4. Secretary, Ministry of Tribal Affairs. 5. Secretary, Ministry of Jal Shakti. 6. Secretary, Ministry of Minority Affairs. 7.Dy. Adviser (School Education), Niti Aayog. 8. Director, NCERT. 9, Vice Chancellor, NIEPA. 10. Chairperson, NCTE 11. Vice Chancellor, IGNOU 1-2, Member Secretary, NCPCR 13. Joint Secretary (Inst.), MHRD, New Delhi 14. JS (AE&Coord), MHRD, New Delhi 15. JS(SS-rr),MHRD 16. JS & FA, MHRD, New Delhi 17. DDG(Stats.), MHRD, New Delhi 18. JS(MDM, MHRD, New Delhi 19. Principal Secretary (Education), UT of Jammu & Kashmir 20.