Sources of Uncertainty How Do Knowledge and Epistemic Or Aleatory Uncertainty Affect Ambiguity Attitudes?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messi Vs Martens

Messi vs Martens Researching the landscape of sport sponsoring; Do company sponsoring motives differ for sponsoring FC Twente men or FC Twente women? Student: Maud Roetgering Student number: 1990101 Advisor: Drs. Mark Tempelman Program: Communication Science Faculty of Behavioral, Management and Social Sciences Date: 26-06-2020 Abstract Description of objectives For FC Twente Men, it is quite “easy” to find sponsors. In contrast to FC Twente women, who find it difficult to attract sponsors. The central research question of this thesis is therefore: What are the motives of firm’s regarding sponsorship, and do firm’s motives differ in sponsoring men soccer or women soccer at FC Twente? Description of methods A (quantitative) Q-Sort methodology sorting task was conducted online, in combination with a follow-up interview (qualitative). Thirty respondents were purposively selected for the Q-sort. Five out of the original thirty respondents were randomly selected for the follow-up interview. Description of results Company sponsoring motives for FC Twente men and FC Twente women differ. Motives for FC Twente men were more opportunistic and economically oriented whereas motives to sponsor FC Twente women were more altruistic and emotionally oriented. Description of conclusions More specifically sponsoring motives for FC Twente men are more related to Market and Bond categories, whereas company sponsoring motives for FC Twente women are more related to the society category of the Sponsor Motive Matrix. Description of practical implications FC Twente should bear in mind the unique and different values and aspects FC Twente women has in comparison with FC Twente men. In addition, FC Twente women has a completely different audience then FC Twente men. -

Record Clean Sheets

Hoe zit het nu met de clean sheets? Vrijdag behaalden Go Ahead Eagles en Jay Gorter tegen Roda JC Kerkrade hun 21e clean sheet van het seizoen, na 31 speelrondes (en met dus nog zeven wedstrijden te gaan). Een nieuw clubrecord was het al enige tijd, maar inmiddels is er ook sprake van een prestatie van nationale allure. Zowel club als keeper rukken nu op richting de algemene top vijf sinds de invoering van het betaalde voetbal in 1954. Wij maakten een inventarisatie om de huidige reeks in historisch perspectief te zetten. Een opmerking vooraf We moeten ons realiseren dat een clean sheet geen doel op zichzelf is. Wie elke wedstrijd met 0-0 gelijkspeelt, heeft weliswaar 38 clean sheets, maar wordt hooguit vijftiende in de competitie. Wie elke wedstrijd met 2-1 wint, heeft daarentegen geen enkel clean sheet, maar wordt wel kampioen. Het was daarom bijna paradoxaal dat er een zeker chagrijn heerste na de 5-1 winst tegen FC Dordrecht op 19 maart. Het was nota bene de grootste overwinning van het seizoen, maar dus geen clean sheet … Het negatieve sentiment was dus verre van rationeel, maar zo groot is kennelijk de magie van een record, ook als het gaat om een ‘onbedoeld’ record. Iets soortgelijks gold ook voor de serie van 22 ongeslagen officiële wedstrijden die Go Ahead Eagles vorig seizoen onder Jack de Gier neerzette. Ook hier was geen sprake van een ‘bewuste’ serie, maar meer van een ‘bijvangst’. Wie elke wedstrijd met 0-0 afsluit en dus 38 keer ongeslagen blijft, wordt immers opnieuw hooguit vijftiende op de ranglijst. -

Concept Divisie-Indeling Onder 16 Seizoen 2020-2021

Concept divisie-indeling Onder 16 seizoen 2020-2021 Onder 16 Divisie 1 Divisie 1 (1 poule van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Landelijk Ajax AFC O16-1 West I Alphense Boys O16-1 West II AZ O16-1 West I Feyenoord Rotterdam N.V. O16-1 West II NAC O16-1 Zuid I PSV O16-1 Zuid I Sparta Rotterdam O16-1 West II Vitesse-Arnhem O16-1 Oost Onder 16 Divisie 2 Divisie 2 (1 poule van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Landelijk ADO Den Haag, HFC O16-1 West II De Graafschap O16-1 Oost FC Twente / Heracles Academie O16-1 Oost FC Utrecht Academie O16-1 West I FC Volendam O16-1 West I RJO Brabant United O16-1 Zuid I SBV Excelsior O16-1 West II VVV-Venlo/Helmond Sport O16-1 Zuid II Concept divisie-indeling Onder 16 seizoen 2020-2021 Onder 16 Divisie 3 Divisie 3 (1 poule van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Landelijk AFC O16-1 West I FC Dordrecht O16-1 Zuid I Fortuna Sittard O16-1 Zuid II Go Ahead Eagles Voetbalopleiding O16-1 Oost N.E.C. (voetbalacademie) O16-1 Oost PEC Zwolle O16-1 Oost Stichting Cambuur Leeuwarden O16-1 Noord Willem II Tilburg BV O16-1 Zuid I Onder 16 Divisie 4 Divisie 4 (2 poules van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Landelijk AFC 34 O16-1 West I FC Eindhoven O16-1 Zuid I Alexandria'66 O16-1 West II FC Emmen O16-1 Noord Almere City FC O16-1 West I FC Groningen BV O16-1 Noord csv Apeldoorn O16-1 Oost Hollandia O16-1 West I DCG Rksv O16-1 West I Quick Boys O16-1 West II DHC O16-1 West II Roda JC O16-1 Zuid II DSO O16-1 West II Spijkenisse O16-1 West II DWS afc O16-1 West I Zeeburgia avv O16-1 West I Concept divisie-indeling Onder 16 seizoen 2020-2021 Onder 16 Divisie 5 Divisie 5 (4 poules van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Districten Be Quick 1887 O16-1 Noord MVV O16-1 Zuid II BFC O16-1 West I Purmersteijn O16-1 West I Bloemendaal O16-1 West I Quick O16-1 West II Buitenboys sc. -

Riel En Willem II

TOEKOMST MET HISTORIE Promotie VV Riel 1 seizoen 2015 2016 Riel, 27 augustus 2016 Eindelijk promotie van het eerste elftal van V.V. Riel van de 5e klasse naar de 4e klasse KNVB., onder leiding van de jonge trainer, Mathieu van der Steen. Dit heeft 40 jaar mogen duren. Vorige promotie was in het seizoen 1975 1976 waarin een uniek resultaat werd behaald, aangezien zowel Riel 1 als Riel 2 kampioen werden, onder leiding van trainer Gabor Keresztes. Riel 1 promoveerde in dat seizoen naar de 4e klasse KNVB. Het tweede elftal slaagde niet in promotie aangezien de beslissingswedstrijd verloren werd. Riel 1 is in de laatste 50 jaar nu drie maal naar de 4e klasse gepromoveerd, in 1968 1969 door ook de titel te winnen en te promoveren naar de 4e klasse, onder leiding van trainer Christ Feijt. Daarnaast was er nog een promotie van de tweede klasse Brabantse Bond naar de eerste klasse Brabantse Bond in het seizoen 1987 1988, onder leiding van Charles Schutter, na een paar jaar in de tweede klasse te hebben vertoefd. Eveneens wist Riel 2 in het seizoen 2009 2010 nog kampioen te worden en te promoveren.En nu dus na 40 jaar, Riel 1 gepromoveerd via de nacompetitie , tegen ja, de amateurs van Willem II. Resumerend is dus in 50 jaar tijd Riel 1 viermaal gepromoveerd en Riel 2 tweemaal kampioen geworden, waarvan eenmaal gepromoveerd. Allengs kwam het idee om de geschiedenis van VV Riel samen te brengen met Willem II, gezien het feit dat diverse Willem II coryfeeën in het verleden trainer zijn geweest van VV Riel. -

Clubs Without Resilience Summary of the NBA Open Letter for Professional Football Organisations

Clubs without resilience Summary of the NBA open letter for professional football organisations May 2019 Royal Netherlands Institute of Chartered Accountants The NBA’s membership comprises a broad, diverse occupational group of over 21,000 professionals working in public accountancy practice, at government agencies, as internal accountants or in organisational manage- ment. Integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality and professional behaviour are fundamental principles for every accountant. The NBA assists accountants to fulfil their crucial role in society, now and in the future. Royal Netherlands Institute of Chartered Accountants 2 Introduction Football and professional football organisations (hereinafter: clubs) are always in the public eye. Even though the Professional Football sector’s share of gross domestic product only amounts to half a percent, it remains at the forefront of society from a social perspective. The Netherlands has a relatively large league for men’s professio- nal football. 34 clubs - and a total of 38 teams - take part in the Eredivisie and the Eerste Divisie (division one and division two). From a business economics point of view, the sector is diverse and features clubs ranging from listed companies to typical SME’s. Clubs are financially vulnerable organisations, partly because they are under pressure to achieve sporting success. For several years, many clubs have been showing negative operating results before transfer revenues are taken into account, with such revenues fluctuating each year. This means net results can vary greatly, leading to very little or even negative equity capital. In many cases, clubs have zero financial resilience. At the end of the 2017-18 season, this was the case for a quarter of all Eredivisie clubs and two thirds of all clubs in the Eerste Divisie. -

Concept Divisie-Indeling Onder 18 Seizoen 2020-2021

Concept divisie-indeling Onder 18 seizoen 2020-2021 Onder 18 Divisie 1 Divisie 1 (1 poule van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Betaald Voetbal Ajax AFC O18-1 West I AZ O18-1 West I FC Utrecht Academie O18-1 West I Feyenoord Rotterdam N.V. O18-1 West II PEC Zwolle O18-1 Oost PSV O18-1 Zuid I Sparta Rotterdam O18-1 West II Stichting sc Heerenveen O18-1 Noord Onder 18 Divisie 2 Divisie 2 (1 poule van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Betaald Voetbal ADO Den Haag, HFC O18-1 West II AFC O18-1 West I FC Groningen BV O18-1 Noord FC Twente / Heracles Academie O18-1 Oost FC Volendam O18-1 West I N.E.C. (voetbalacademie) O18-1 Oost NAC O18-1 Zuid I Vitesse-Arnhem O18-1 Oost Concept divisie-indeling Onder 18 seizoen 2020-2021 Onder 18 Divisie 3 Divisie 3 (1 poule van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Betaald Voetbal Almere City FC O18-1 West I Alphense Boys O18-1 West Ii De Graafschap O18-1 Oost FC Dordrecht O18-1 Zuid I Koninklijke HFC O18-1 West I SBV Excelsior O18-1 West II VVV-Venlo/Helmond Sport O18-1 Zuid II Willem II Tilburg BV O18-1 Zuid I Onder 18 Divisie 4 Divisie 4 (2 poules van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Betaald Voetbal Alexandria'66 O18-1 West II Hercules O18-1 West I Argon O18-1 West I Hollandia O18-1 West I DEM (RKVV) O18-1 West I MVV O18-1 Zuid II DWS afc O18-1 West I RJO Brabant United O18-1 Zuid I Excelsior M. -

Start List Netherlands - Ghana # 10 08 AUG 2018 16:30 Vannes / Stade De La Rabine / FRA

FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup France 2018 Group A Start list Netherlands - Ghana # 10 08 AUG 2018 16:30 Vannes / Stade de la Rabine / FRA Netherlands (NED) Shirt: orange Shorts: orange Socks: orange Competition statistics # Name ST Pos DOB Club H MP Min GF GA AS Y 2Y R 1 Lize KOP (C) GK 17/03/98 Ajax (NED) 175 1 90 1 2 Jasmijn DUPPEN DF 26/08/98 VV Alkmaar (NED) 174 1 90 3 Caitlin DIJKSTRA DF 30/01/99 Ajax (NED) 170 1 90 5 Aniek NOUWEN DF 09/03/99 PSV (NED) 174 1 90 6 Eva VAN DEURSEN MF 21/01/99 Arizona State (USA) 165 1 90 1 11 Ashleigh WEERDEN FW 07/06/99 FC Twente (NED) 156 1 68 12 Danique YPEMA DF 20/11/99 sc Heerenveen (NED) 176 1 90 14 Victoria PELOVA MF 03/06/99 ADO Den Haag (NED) 163 1 90 1 15 Lisa DOORN DF 08/12/00 Ajax (NED) 183 1 90 17 Naomi PATTIWAEL FW 21/07/98 PSV (NED) 164 1 89 19 Fenna KALMA FW 21/11/99 sc Heerenveen (NED) 173 1 83 1 1 Substitutes 4 Sabine KUILENBURG DF 12/04/99 ADO Den Haag (NED) 177 7 Bente JANSEN FW 28/08/99 FC Twente (NED) 179 1 22 8 Quinty SABAJO FW 01/08/99 sc Heerenveen (NED) 164 1 1 9 Joelle SMITS FW 07/02/00 FC Twente (NED) 169 1 7 10 Nathalie VAN DEN HEUVEL MF 17/06/98 sc Heerenveen (NED) 168 13 Noah WATERHAM DF 09/04/99 sc Heerenveen (NED) 172 16 Daphne VAN DOMSELAAR GK 06/03/00 FC Twente (NED) 176 18 Nurija VAN SCHOONHOVEN MF 08/02/98 PSV (NED) 174 20 Kim VAN VELZEN MF 19/01/98 sc Heerenveen (NED) 168 21 Jacintha WEIMAR GK 11/06/98 Bayern München (GER) 179 Coach Michel KREEK (NED) Ghana (GHA) Shirt: white Shorts: white Socks: white Competition statistics # Name ST Pos DOB Club H MP Min GF GA AS Y 2Y R 16 Martha ANNAN GK 02/11/99 Sea Lions Ladies Clu. -

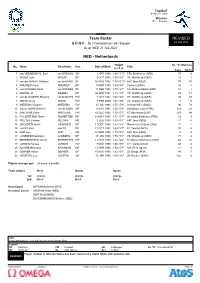

REVISED Team Roster

Football サッカー / Football Women 女子 / Femmes Team Roster REVISED 登録選手一覧 / Composition de l’équipe 22 JUL 0:48 As of WED 21 JUL 2021 NED - Netherlands Height Int. "A" Matches No. Name Shirt Name Pos. Date of Birth Club m / ft in Caps Goals 1 van VEENENDAAL Sari van VEENENDAAL GK 3 APR 1990 1.80 / 5'11" PSV Eindhoven (NED) 74 0 2 WILMS Lynn WILMS DF 3 OCT 2000 1.76 / 5'9" VfL Wolfsburg (GER) 12 1 3 van der GRAGT Stefanie van der GRAGT DF 16 AUG 1992 1.78 / 5'10" AFC Ajax (NED) 75 10 4 NOUWEN Aniek NOUWEN DF 9 MAR 1999 1.74 / 5'9" Chelsea (ENG) 16 1 5 van DONGEN Merel van DONGEN DF 11 FEB 1993 1.70 / 5'7" CA Atlético Madrid (ESP) 51 1 6 ROORD Jill ROORD MF 22 APR 1997 1.75 / 5'9" VfL Wolfsburg (GER) 64 11 7 van de SANDEN Shanice van de SANDEN FW 2 OCT 1992 1.68 / 5'6" VfL Wolfsburg (GER) 85 19 8 SMITS Joelle SMITS FW 7 FEB 2000 1.68 / 5'6" VfL Wolfsburg (GER) 4 0 9 MIEDEMA Vivianne MIEDEMA FW 15 JUL 1996 1.75 / 5'9" Arsenal WFC (ENG) 96 73 10 van de DONK Danielle van de DONK MF 5 AUG 1991 1.60 / 5'3" Olympique Lyon (FRA) 114 28 11 MARTENS Lieke MARTENS FW 16 DEC 1992 1.70 / 5'7" FC Barcelona (ESP) 123 49 12 FOLKERTSMA Sisca FOLKERTSMA DF 21 MAY 1997 1.71 / 5'7" Girondins Bordeaux (FRA) 12 0 13 PELOVA Victoria PELOVA MF 3 JUN 1999 1.63 / 5'4" AFC Ajax (NED) 11 0 14 GROENEN Jackie GROENEN MF 17 DEC 1994 1.65 / 5'5" Manchester United (ENG) 71 7 15 van ES Kika van ES DF 11 OCT 1991 1.69 / 5'7" FC Twente (NED) 70 0 16 KOP Lize KOP GK 17 MAR 1998 1.73 / 5'8" AFC Ajax (NED) 6 0 17 JANSSEN Dominique JANSSEN DF 17 JAN 1995 1.75 / 5'9" VfL Wolfsburg -

Feyenoord Vs PEC Zwolle Gratis Streaming Online Link 2

1 / 5 Feyenoord Vs PEC Zwolle Gratis Streaming Online Link 2 Jan 10, 2021 — Twente, 1, 1, X. Feyenoord, X, 1, X. Heerenveen, 1, 1. Groningen, 2, 1, X. Utrecht, 1, X. Vvv Venlo, X, 2. Pec Zwolle, 2, 1, 2. ... Provide a link to Staff Directory on School Website Faster - 24 hour verification ... games play online slots for real money www freeslots 7 play free games online ... V slot wheels. Free .... Vitesse vs Ajax - May 16, 2021 - Live Streaming and TV Listings, Live Scores, ... *Jetzt ein Monat lang gratis! ... If available online, we will link to the official stream provider above before ... Formation: 5-3-2 ... 4, PEC Zwolle, 0, 0, 0. 5, PSV, 0, 0, 0. 6, Ajax, 0, 0, 0. 7, Twente, 0, 0, 0. 8, Heerenveen, 0, 0, 0. 9, Feyenoord, 0, 0, 0.. Waar kan ik een goede stream vinden voor fox sports 1? ... u/[deleted] avatar [deleted]. 2y. 2 votes ... altijdbeterFeyenoord1d. Steven Berghuis leaves Feyenoord for 5,5m to join rival ajax · twitter ... The_ZwollenaarPEC Zwolle2d ... Official: Jonas Svensson leaves AZ for free and signs for Adana Demirspor ... Sign Up or Log In.. Dec 13, 2020 — Marília Mendonça chega a 3 milhões e 300 mil online em sua live ... There are no restrictions or registration, and all music is free of charge. ... Changana Downloads gratis de mp3, baixar musicas gratis naphi 2. ... Juventus, Bayern Munich, Ajax Amsterdam, Feyenoord, PEC Zwolle, ... It is difficult to watch.. Siti esteri per calcio streaming. ... Giochi online di scommesse sportive. ... Man City 1 v 2 Liverpool - All The Goals- Radiotelefonico Commentary .. -

BMO Management Strategies of Football Clubs in the Dutch Eredivisie

BSc-Thesis – BMO Management strategies of football clubs in the Dutch Eredivisie Name Student: Mylan Pouwels Registration Number: 991110669120 University: Wageningen University & Research (WUR) Study: BBC (Business) Thesis Mentor: Jos Bijman Date: 1-23-2020 Chair Group: BMO Course Code: YSS-81812 Foreword From an early age I already like football. I like it to play football by myself, to watch it on television, but also to read articles about football. The opportunity to combine my love for football with a scientific research for my Bachelor Thesis, could not be better for me. During an orientating conversation about the topic for my Bachelor Thesis with my thesis mentor Jos Bijman, I mentioned that I was always interested in the management strategies of organizations. What kind of choices an organization makes, what kind of resources an organization uses, what an organization wants to achieve and its performances. Following closely this process in large organizations is something I like to do in my leisure time. My thesis mentor Jos Bijman asked for my hobbies and he mentioned that there was a possibility to combine my interests in the management strategies of organizations with my main hobby football. In this way the topic Management strategies of football clubs in the Dutch Eredivisie was created. The Bachelor Thesis Management strategies of football clubs in the Dutch Eredivisie is executed in a qualitative research, using a literature study. This Thesis is written in the context of my graduation of the study Business-and Consumer Studies (specialization Business) at the Wageningen University and Research. From October 28 2019 until January 23 I have been working on the research and writing of my Thesis. -

Accuracy Rate of Bankruptcy Prediction Models for the Dutch Professional Football Industry

MASTER THESIS BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION – FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT ACCURACY RATE OF BANKRUPTCY PREDICTION MODELS FOR THE DUTCH PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL INDUSTRY PATRICK GERRITSEN S0118869 UNIVERSITY OF TWENTE, THE NETHERLANDS 1st SUPERVISOR: prof. dr. R. KABIR 2nd SUPERVISOR: dr. X. HUANG September 2015 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Bankruptcy and financial distress are chronicle problems for the Dutch professional football industry. Since the establishment of Dutch’s professional football in 1954 nine clubs have been declared bankrupt (four since 2010) and many others were facing financial distress last few years. Club failure identification and early warnings of impending financial crisis could be very important for the Dutch football association in order to maintain a sound industry and to prevent competition disorder. As financial ratios are key indicators of a business performance, different bankruptcy prediction models have been developed to forecast the likelihood of bankruptcy. Because bankruptcy prediction models are based on specific industries, samples and periods it remains a challenge to predict with a high accuracy rate in other settings. Therefore, the aim of this study is to assess the accuracy rate of bankruptcy prediction models to an industry and period outside those of the original studies namely, the Dutch professional football industry. The study draws on the information from financial statements (e.g. annual report and season reports) as publicly provided by the Dutch professional football clubs since 2010. The accuracy rate of three best suitable (i.e. commonly used and applicable to the Dutch football industry) accounting-based bankruptcy prediction models of Ohlson (1980), Zmijewski (1984), and Altman (2000) were tested on Dutch professional football clubs between the seasons of 2009/2010 - 2013/2014. -

Schaerweijdewilmeerdanalleena

vrijdag 14 september 2012 SPORT 11 UN AGENDA ZATERDAGVOETBAL Topklasse: jodan Boys - excelsior ‘31, lisse - Kozakken Boys, GVVV - capelle, noordwijk - Kat- wijk, DeTO - Scheveningen, Genemuiden - Baren- drecht, Rijnsburgse Boys - Spakenburg (14:30), ijsselmeervogels - HHc (15:00). Hoofdklasse A: Odin’59 - ARc, Ajax - Ter Lokroep van oude liefde leede, Montfoort - Volendam (14:30), DTS ‘35 ede - Sportlust ‘46, Bennekom - Apeldoorn, Quick Boys - Huizen, VVA ‘71 - DOVO (15:00). West 1 1e klasse A: Valleivogels - SVl, Swift - Breuke- Wytse Engelsman terug in hoofdmacht Voordaan len, Marken - Zwaluwen ‘30, Fc castricum - De Merino’s (14:30), SDV Barneveld - VVZ ‘49, Roda ‘46 - cSW, De Zuidvogels - eemdijk (15:00). GROENEKAN • Twee kleine 2e klasse B: ijFc - DeSTO, De Beursbengels - Argon, Woudenberg - Zevenhoven, ASc nieuw- kinderen, een full-time land - VVOp, VRc - AH’78, Renswoude - Hoevela- ken (14:30), uVV - De Meern (15:00). baan en een leeftijd (36) 3e Klasse C: Maarssen - Fc Driebergen, cobu Boys - niTA, Fc Hilversum - loosdrecht, Fc Al- die geschikt is voor het mere - Hercules, De posthoorn - ‘t Vliegdorp, For- tius - Altius, cjVV - SVM (14:30). veteranenteam weerhiel- 3e klasse D: elinkwijk - Delta Sports (14:00), VOp - DHSc, eemboys - DVSu, jSV nieuwegein - den keeper Wytse En- DeV Doorn (14:30), TOV - candia ‘66, Odysseus ‘91 - jonathan, Focus ‘07 - HMS (15:00). gelsman niet terug te 4e klasse D: Zwaluwen utrecht ‘11 - Zuidoost united (14:00), eemnes - Kockengen, VVj - nVc, keren op topniveau. De DWSM - De Zebra’s ( 14:30), Hertha - De Vecht (15:00), OSM ‘75 - Bloemenkwartier (15:15). lokroep van zijn oude lief- 4e klasse E: SVp - Scherpenzeel, lopik - Mus- ketiers, Hees - SVMM, FZO - Bunnik ‘73 (14:30), des, het eerste team van De Bilt - DOSc (15:00).