Communalism #15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN INTERVENTIONS in DEMOCRATIC THEORY by BRIAN CARL BERNHARDT B.A., James Madison University, 2005 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2010

BEYOND THE DEMOCRATIC STATE: ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN INTERVENTIONS IN DEMOCRATIC THEORY by BRIAN CARL BERNHARDT B.A., James Madison University, 2005 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science 2014 This thesis entitled: Beyond the Democratic State: Anti-Authoritarian Interventions in Democratic Theory written by Brian Carl Bernhardt has been approved for the Department of Political Science Steven Vanderheiden, Chair Michaele Ferguson David Mapel James Martel Alison Jaggar Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Bernhardt, Brian Carl (Ph.D., Political Science) Beyond the Democratic State: Anti-Authoritarian Interventions in Democratic Theory Thesis directed by Associate Professor Steven Vanderheiden Though democracy has achieved widespread global popularity, its meaning has become increasingly vacuous and citizen confidence in democratic governments continues to erode. I respond to this tension by articulating a vision of democracy inspired by anti-authoritarian theory and social movement practice. By anti-authoritarian, I mean a commitment to individual liberty, a skepticism toward centralized power, and a belief in the capacity of self-organization. This dissertation fosters a conversation between an anti-authoritarian perspective and democratic theory: What would an account of democracy that begins from these three commitments look like? In the first two chapters, I develop an anti-authoritarian account of freedom and power. -

The Rise of Ethical Anarchism in Britain, 1885-1900

1 e[/]pater 2 sie[\]cle THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 By Mark Bevir Department of Politics Newcastle University Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU U.K. ABSTRACT In the nineteenth century, anarchists were strict individualists favouring clandestine organisation and violent revolution: in the twentieth century, they have been romantic communalists favouring moral experiments and sexual liberation. This essay examines the growth of this ethical anarchism in Britain in the late nineteenth century, as exemplified by the Freedom Group and the Tolstoyans. These anarchists adopted the moral and even religious concerns of groups such as the Fellowship of the New Life. Their anarchist theory resembled the beliefs of counter-cultural groups such as the aesthetes more closely than it did earlier forms of anarchism. And this theory led them into the movements for sex reform and communal living. 1 THE RISE OF ETHICAL ANARCHISM IN BRITAIN 1885-1900 Art for art's sake had come to its logical conclusion in decadence . More recent devotees have adopted the expressive phase: art for life's sake. It is probable that the decadents meant much the same thing, but they saw life as intensive and individual, whereas the later view is universal in scope. It roams extensively over humanity, realising the collective soul. [Holbrook Jackson, The Eighteen Nineties (London: G. Richards, 1913), p. 196] To the Victorians, anarchism was an individualist doctrine found in clandestine organisations of violent revolutionaries. By the outbreak of the First World War, another very different type of anarchism was becoming equally well recognised. The new anarchists still opposed the very idea of the state, but they were communalists not individualists, and they sought to realise their ideal peacefully through personal example and moral education, not violently through acts of terror and a general uprising. -

Charlotte Wilson, the ''Woman Question'', and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism

IRSH, Page 1 of 34. doi:10.1017/S0020859011000757 r 2011 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Charlotte Wilson, the ‘‘Woman Question’’, and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism S USAN H INELY Department of History, State University of New York at Stony Brook E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: Recent literature on radical movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has re-cast this period as a key stage of contemporary globali- zation, one in which ideological formulations and radical alliances were fluid and did not fall neatly into the categories traditionally assigned by political history. The following analysis of Charlotte Wilson’s anarchist political ideas and activism in late Victorian Britain is an intervention in this new historiography that both supports the thesis of global ideological heterogeneity and supplements it by revealing the challenge to sexual hierarchy that coursed through many of these radical cross- currents. The unexpected alliances Wilson formed in pursuit of her understanding of anarchist socialism underscore the protean nature of radical politics but also show an over-arching consensus that united these disparate groups, a common vision of the socialist future in which the fundamental but oppositional values of self and society would merge. This consensus arguably allowed Wilson’s gendered definition of anarchism to adapt to new terms as she and other socialist women pursued their radical vision as activists in the pre-war women’s movement. INTRODUCTION London in the last decades of the nineteenth century was a global crossroads and political haven for a large number of radical activists and theorists, many of whom were identified with the anarchist school of socialist thought. -

Social Ecology and Communalism

Murray Bookchin Bookchin Murray $ 12,95 / £ xx,xx Social Ecology and Communalism Replace this text Murray Bookchin ocial cology Social Ecology and Communalism and Communalism Social Ecology S E and Communalism AK Press Social Ecology and Communalism Murray Bookchin Social Ecology and Communalism Bookchin, Murray Social Ecology and Communalism Library of Congress Control Number 2006933557 ISBN 978-1-904859-49-9 Published by AK Press © Eirik Eiglad and Murray Bookchin 2006 AK Press 674–A 23rd St. Oakland, CA 94612 USA www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press UK PO Box 12766 Edinburgh, EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555–5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] Design and layout by Eirik Eiglad Contents An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism 7 What is Social Ecology? 19 Radical Politics in an Era of Advanced Capitalism 53 The Role of Social Ecology in a Period of Reaction 68 The Communalist Project 77 After Murray Bookchin 117 An Introduction to Social Ecology and Communalism We are standing at a crucial crossroads. Not only does the age- old “social question” concerning the exploitation of human labor remain unresolved, but the plundering of natural resources has reached a point where humanity is also forced to politically deal with an “ecological question.” Today, we have to make conscious choices about what direction society should take, to properly meet these challenges. At the same time, we see that our very ability to make the necessary choices are being undermined by an incessant centralization of economic and political power. Not only is there a process of centralization in most modern nation states that divests humanity of any control over social affairs, but power is also gradually being transferred to transnational institutions. -

Bookchin's Libertarian Municipalism

BOOKCHIN’S LIBERTARIAN MUNICIPALISM Janet BIEHL1 ABSTRACT: The purpose of this article is to present the Libertarian Municipalism Theory developed by Murray Bookchin. The text is divided into two sections. The first section presents the main precepts of Libertarian Municipalism. The second section shows how Bookchin’s ideas reached Rojava in Syria and is influencing the political organization of the region by the Kurds. The article used the descriptive methodology and was based on the works of Murray Bookchin and field research conducted by the author over the years. KEYWORDS: Murray Bookchin. Libertarian Municipalism. Rojava. Introduction The lifelong project of the American social theorist Murray Bookchin (1921-2006) was to try to perpetuate the centuries-old revolutionary socialist tradition. Born to socialist revolutionary parents in the Bronx, New York, he joined the international Communist movement as a Young Pioneer in 1930 and trained to become a young commissar for the coming proletarian revolution. Impatient with traditional secondary education, he received a thoroughgoing education in Marxism-Leninism at the Workers School in lower Manhattan, immersing himself in dialectical materialism and the labor theory of value. But by the time Stalin’s Soviet Union formed a pact with Nazi Germany (in the sum- mer of 1939), he cut his ties with the party to join the Trotskyists, who expected World War II to end in international proletarian revolutions. When the war 1 Janet Biehl is an American political writer who is the author of numerous books and articles associated with social ecology, the body of ideas developed and publicized by Murray Bookchin. -

Was the Inca Empire a Socialist State? A

INCA EMPIRE 55 WAS THE INCA EMPIRE A SOCIALIST STATE? A HISTORICAL DISCUSSION meadow, and they tilled in common a portion of the agricultural land for the support of the chief, the cult 2 Kevin R. Harris and the aged. However, not all land was used for communal purposes all Before the Spanish conquest of the Americas in the fifteenth and the time. Sometimes individual members of the community used sixteenth centuries, the Inca Empire spread down much of the the land for a period of time for personal use. Llamas and modern South American coast in the Andes Mountains. The alpacas also grazed on the land. These large animals were used empire consisted of more than ten million inhabitants and had, for work and their wool was used to make clothing in the Inca 3 at the time, a very unique political and economic system. The State. When a common couple was married the community 4 government divided land and animals amongst members of the built them a modest house. It was a custom in Incan society for nation, not necessarily equally, and a system was in place to take people to help others in the community who were in need. care of the elderly and sick. Social scientists have been debating “People were expected to lend their labor to cultivate neighbors’ how to classify the Inca Empire for centuries. Arguments have land, and expected that neighbors would help them in due been made which classified the Inca Empire as a socialist state. course. All capable people were collaborated to support the Many elements of socialism existed in the Inca Empire, but can incapable—orphans, widows, the sick—with food and 5 the state really be classified as socialistic? housing.” Inca commoners expected this courtesy from their The Incas moved into the area which is now known as the neighbors. -

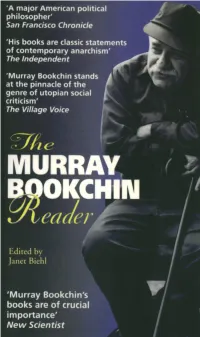

The Murray Bookchin Reader

The Murray Bookchin Reader We must always be on a quest for the new, for the potentialities that ripen with the development of the world and the new visions that unfold with them. An outlook that ceases to look for what is new and potential in the name of "realism" has already lost contact with the present, for the present is always conditioned by the future. True development is cumulative, not sequential; it is growth, not succession. The new always embodies the present and past, but it does so in new ways and more adequately as the parts of a greater whole. Murray Bookchin, "On Spontaneity and Organization," 1971 The Murray Bookchin Reader Edited by Janet Biehl BLACK ROSE BOOKS Montreal/New York London Copyright © 1999 BLACK ROSE BOOKS No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system-without written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from the Canadian Reprography Collective, with the exception of brief passages quoted by a reviewer in a newspaper or magazine. Black Rose Books No. BB268 Hardcover ISBN: 1-55164-119-4 (bound) Paperback ISBN: 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-71026 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Bookchin, Murray, 1921- Murray Bookchin reader Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55164-119-4 (bound). ISBN 1-55164-118-6 (pbk.) 1. Libertarianism. 2. Environmentalism. 3. Human ecology. -

Rethinking Property, Money and Banking

Rethinking Property, Money and Banking: Social Ownership, Self-Management and Mutuality in the Anarchist Economy Carlota Moreno Villar (11063556) University of Amsterdam MSc Thesis Political Science (International Relations) Word count: 23761 Date: June 2020 Thesis group Alternatives to Capitalism: Models of Future Society Supervisor Dr. Annette Freyberg-Inan Second Reader Dr. Paul Raekstad 1 Abstract Capitalism is a social, political and economic system embedded in history which inherently creates inequality and oppressive social relations. The main sources of inequality and oppression in capitalism are private property and the monetary system —which fuel the process of accumulation— and the racial and colonial nature of capitalism. The focus of this thesis will be on private property and money. Money and monetary policy will be analysed from a heterodox sociological and historical perspective. The aim of this thesis will be to propose economic reforms that are conducive to the development of an alternative anarchist economy, incorporating insights from heterodox economic theory and grassroots economic experiments. The thesis will argue that the fundamental values of anarchism are equality, freedom and solidarity. Further, it will propose three principles of allocation that should guide an anarchist economy. Namely, self-management, mutuality and social ownership. The economic reforms that follow these principles, and which are conducive to the development of an anarchist economy, include the introduction of complementary currencies -

A Social-Ecological Perspective on Degrowth As a Political Ideology

Capitalism Nature Socialism ISSN: 1045-5752 (Print) 1548-3290 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcns20 Beyond the Limits of Nature: A Social-ecological Perspective on Degrowth as a Political Ideology Eleanor Finley To cite this article: Eleanor Finley (2018): Beyond the Limits of Nature: A Social-ecological Perspective on Degrowth as a Political Ideology, Capitalism Nature Socialism, DOI: 10.1080/10455752.2018.1499122 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2018.1499122 Published online: 23 Jul 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 36 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcns20 CAPITALISM NATURE SOCIALISM https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2018.1499122 Beyond the Limits of Nature: A Social-ecological Perspective on Degrowth as a Political Ideology Eleanor Finley Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA ABSTRACT This article offers a critical analysis of the ideological position of degrowth from the perspective of social ecology. It agrees with Giorgios Kallis’ call to abolish the growth imperative that capitalism embodies today, but it also presents a critique of the conceptual underpinnings of this notion. More precisely, I argue that degrowth as an ideological platform reproduces a binary conception of society and nature, an oppositional mentality which is a key concept to hierarchical epistemology. Degrowth as a political agenda is thus prone to appropriation to authoritarian ends. In order to temper this tendency and help degrowth as a tool of analysis reach its liberatory potential, I advocate its consideration alongside a social-ecological position. -

The Theory of Developmental Communalism: Description and Bibliography

The Theory of Developmental Communalism: Description and Bibliography Updated September 2019 by Donald Elden Pitzer Professor Emeritus of History, Director Emeritus, Center for Communal Studies University of Southern Indiana, Evansville, Indiana 47712, [email protected] Developmental communalism is both a theory and a process. As a theory, it focuses on movements that choose the communal method of organizing and the adjustments they make to their organizational structures, beliefs, and practices to insure the survival and expansion of the movements. Developmental communalism theory recognizes that communal living is a universally available social mechanism in all times to all peoples, governments, and movements. Secular as well as religious movements adopt communal living, often in a vulnerable early stage because it promises security, solidarity, and survival. Developmental communalism sees communitarianism as a method of social change with both advantages and disadvantages compared to individualism, gradual reform and revolution. Communitarianism is immediate, voluntary, collective, non-violent, and experimental, but it can be isolating, authoritarian, and especially difficult if it attempts communities that require all the elements of a social microcosm. As a process, developmental communalism is an adaptive continuum in both individual communities and the larger movements that found them. To survive over long periods of time, communal groups and their founding movements must adapt to changing realities within and without. The process of developmental communalism poses a double-jeopardy threat to both communal groups and their movements. If communal living becomes an unchangeable commitment, the founding movement may fail to make necessary adjustments, stagnate, and die, thus causing the death of its communal groups. -

MORAL ECONOMY: CLAIMS for the COMMON GOOD by Elizabeth D

MORAL ECONOMY: CLAIMS FOR THE COMMON GOOD By Elizabeth D. Mauritz A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Philosophy – Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT MORAL ECONOMY: CLAIMS FOR THE COMMON GOOD By Elizabeth D. Mauritz The cases, issues, and theoretical convictions of the social science work on the concept ‘Moral Economy’ are explored to develop a full understanding of what divergent theories and accounts share in common and to gauge the philosophical relevance of Moral Economy. The work of E.P. Thompson, James Scott, William Booth, Thomas Arnold, and Daniel Little are featured along with contemporary cases of Moral Economy. Conceptual clarification is guided by the categorization of common qualities including the scope of application, whether it is used historically or normatively, relevant time frame, nature of the community, goals that motivate practitioners, and how people are epistemically situated in relation to the Moral Economy under consideration. Moral Economy is identified here as a community centered response, arising from a sense of common good, reinforced by custom or tradition, to an unjust appropriation or abuse of land, labor, human dignity, natural resources, or material goods; moreover, it is the regular behaviors producing social arrangements that promote just relations between unequal persons or groups within a community to achieve long-term social sustainability. I argue that the moral economists are right to insist that people regularly make collective claims and take action on behalf of their communities for reasons that are not primarily self-interested. Furthermore, I demonstrate that social ethics and political behavior are culturally and temporally contextual, i.e. -

Libertarian Socialism

Libertarian Socialism PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 12 Aug 2012 19:52:27 UTC Contents Articles Libertarian socialism 1 The Venus Project 37 The Zeitgeist Movement 39 References Article Sources and Contributors 42 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 43 Article Licenses License 44 Libertarian socialism 1 Libertarian socialism Libertarian socialism (sometimes called social anarchism,[1][2] and sometimes left libertarianism)[3][4] is a group of political philosophies that promote a non-hierarchical, non-bureaucratic society without private property in the means of production. Libertarian socialists believe in converting present-day private productive property into the commons or public goods, while retaining respect for personal property[5]. Libertarian socialism is opposed to coercive forms of social organization. It promotes free association in place of government and opposes the social relations of capitalism, such as wage labor.[6] The term libertarian socialism is used by some socialists to differentiate their philosophy from state socialism[7][8] or by some as a synonym for left anarchism.[1][2][9] Adherents of libertarian socialism assert that a society based on freedom and equality can be achieved through abolishing authoritarian institutions that control certain means of production and subordinate the majority to an owning class or political and economic elite.[10] Libertarian socialism also constitutes a tendency of thought that