Top Ten Species Reliant on Zoos 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiger Conservation- Central India

TIGER CONSERVATION- CENTRAL INDIA LOCATION OF KTR Kawal Tiger Reserve Background Initially was a Kawal wildlife sanctuary in 1999 with an area of 892.93 Sq.Km. During 2010 All India Estimation the decline in tiger population in Northern Andhra Pradesh prompted the Govt. of A.P. to consolidate the main tiger area of North Andhra Pradesh. SIGNIFICANCE To protect the biodiversity of Deccan plateau of Sahyadri Mountain Ranges along with ecological processes and conservation of wild gene pool. What are there in Kawal ? Area of Tiger Reserve : 892.23 Sq.km ( Core) 1123.21 (Buffer ) No. of Plants present : 673 species Amphibians : 10 species Reptiles : 34 species Birds / avifauna : 310 species Mammals : 68 Species. Important plant species present : Teak, Rosewood, Diospyros, Anogeisus, Hardwickia, Chloroxylon and Bamboo. Important Mammals : Tiger, Slothbear, Indian Gaur, Wild dog, Wolf, Ratel, Deers ( Chital and Sambar ), Antelopes ( Black buck, Gazelle, NIlgai & Chowsinga). UNIQUENESS OF KAWAL ANTELOPES OF KAWAL Spotted Deer Sambhar INDIA’S NATIONAL BIRD Monitoring of Wildlife in Kawal Contd: Contd: THREATS CONTINUE - KAWAL Habitat destruction Smuggling and felling Extensive sand mining Encroachment Poaching AICHI TARGET 11-To restore the bio diversity 2012- Tiger reserve, included 1123 sq km forest. What has been done in the past 2 years in Kawal to achieve the Aichi Biodiversity targets? AICHI TARGET 5- Habitat improvement works Grass land development • Natural water source development • Construction of check dam • Construction of saucer pits in fringe areas AICHI TARGET 9-Fodder development Obnoxious weeds have been removed in 300 Ha and (12) Locations attempts made to improve fodder by brushwood fencing of 4-5 feet and planting with the fodder species in the gaps by racking the soil, duly removing weeds in the area. -

Beyond the Stripes: Save Tigers Save So

REPORT T2x 2017 BEYOND THE STRIPES SAVE TIGERS, SAVE SO MUCH MORE Front cover A street art painting of a tiger along Brick Lane, London by artist Louis Masai. © Stephanie Sadler FOREWORD: SEEING BEYOND THE STRIPES 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INTRODUCTION 8 1. SAVING A BIODIVERSITY TREASURE TROVE 10 Tigers and biodiversity 12 Protecting flagship species 14 WWF Acknowledgements Connecting landscapes 16 WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced We would like to thank all the tiger-range governments, independent conservation organizations, with over partners and WWF Network offices for their support in the Driving political momentum 18 25 million followers and a global network active in more production of this report, as well as the following people in Return of the King – Cambodia and Kazakhstan 20 than 100 countries. particular: WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s Working Team natural environment and to build a future in which people 2. BENEFITING PEOPLE: CRITICAL ECOSYSTEM SERVICES 22 Michael Baltzer, Michael Belecky, Khalid Pasha, Jennifer live in harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s Safeguarding watersheds and water security 24 biological diversity, ensuring that the use of renewable Roberts, Yap Wei Lim, Lim Jia Ling, Ashleigh Wang, Aurelie natural resources is sustainable, and promoting the Shapiro, Birgit Zander, Caroline Snow, Olga Peredova. Tigers and clean water – India 26 reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. Edits and Contributions: Sejal Worah, Vijay Moktan, Mitigating climate change 28 A WWF International production Thibault Ledecq, Denis Smirnov, Zhu Jiang, Liu Peiqi, Arnold Tigers, carbon and livelihoods – Russian Far East 30 Sitompul, Mark Rayan Darmaraj, Ghana S. -

EAZA Tiger Campaign

B USHMEAT | R AINFOREST | T I GER | S HELLSHOCK | R HINO | M ADAGASCAR | A MPHIBIAN | C ARNIVORE | A PE EAZA Conservation Campaigns Over the last ten years Europe’s leading zoos and EAZA Tiger aquariums have worked together in addressing a variety of issues affecting a range of species and habitats. EAZA’s annual conservation campaigns have Campaign raised funds and promoted awareness amongst 2002-2004 millions of zoo visitors each year, as well as providing the impetus for key regulatory change. | INTRODUCTION | The Tiger campaign was EAZA's third campaign and the first to run for two years, from September 2002 until September 2004. It was launched to raise awareness for the conservation concerns facing tigers in the wild. About a century ago seven to eight subspecies of tiger still roamed the planet, but due to habitat loss, hunting and illegal wildlife trade three subspecies became extinct. For this campaign EAZA collaborated with 21st Century Tiger, a wild tiger conservation partnership between the Zoological Society of London and Global Tiger Patrol, which raises funds for tiger conservation projects in the field. | CAMPAIGN AIMS | Data suggests that in 2008 there were about 3,800 to 5,180 tigers left in the wildi, and their populations are shrinking further due to increased human activity. Their habitats across Asia are confined, small and isolated. The EAZA Tiger Campaign aimed, therefore, to promote awareness of the threats tigers face in their natural habitats, while at the same time raising the profile of zoos as conservation organisations. Additionally it was aimed to raise funds to support wild tiger conservation projects. -

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Speciestm

Species 2014 Annual ReportSpecies the Species of 2014 Survival Commission and the Global Species Programme Species ISSUE 56 2014 Annual Report of the Species Survival Commission and the Global Species Programme • 2014 Spotlight on High-level Interventions IUCN SSC • IUCN Red List at 50 • Specialist Group Reports Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis), Endangered. © Martin Harvey Muhammad Yazid Muhammad © Amazing Species: Bleeding Toad The Bleeding Toad, Leptophryne cruentata, is listed as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. It is endemic to West Java, Indonesia, specifically around Mount Gede, Mount Pangaro and south of Sukabumi. The Bleeding Toad’s scientific name, cruentata, is from the Latin word meaning “bleeding” because of the frog’s overall reddish-purple appearance and blood-red and yellow marbling on its back. Geographical range The population declined drastically after the eruption of Mount Galunggung in 1987. It is Knowledge believed that other declining factors may be habitat alteration, loss, and fragmentation. Experts Although the lethal chytrid fungus, responsible for devastating declines (and possible Get Involved extinctions) in amphibian populations globally, has not been recorded in this area, the sudden decline in a creekside population is reminiscent of declines in similar amphibian species due to the presence of this pathogen. Only one individual Bleeding Toad was sighted from 1990 to 2003. Part of the range of Bleeding Toad is located in Gunung Gede Pangrango National Park. Future conservation actions should include population surveys and possible captive breeding plans. The production of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is made possible through the IUCN Red List Partnership. -

Tiger Conservation Enhancement in Bhutan

Final Report TIGER CONSERVATION ENHANCEMENT IN BHUTAN (January 2000 – June 2001) WWF-Bhutan Program Chubachu PB 210 Thimphu July 2001 TIGER CONSERVATION ENHANCEMENT IN BHUTAN Final report to the Save the Tiger Fund of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Submitted July 2001 by World Wildlife Fund Project #1999-0268-093 (January 2000 to June 2001) This final report presents the cumulative achievement of the Tiger Conservation Enhancement Project in Bhutan initiated in January of 2000 and funded by the Save the Tiger Fund. INTRODUCTION Bhutan occupies a unique position within the environment and development debate. Its late entry into the development race has given Bhutan the opportunity to learn from the experiences of its neighbors. Moreover, Bhutan has had the option of carefully building an environmentally sustainable and culturally appropriate development strategy. Accordingly, approximately 72 percent of Bhutan’s forests are still intact, of which 60 percent is to be protected and maintained in the future as decided by the 73rd session of the Bhutan National Assembly. Over a quarter of the kingdom is under an extensive network of protected areas, and another 9 percent of the kingdom is included in a network of biological corridors connecting the nine different protected areas. Bhutan’s tiger population is estimated somewhere between115 and 150, with approximately 70 to 80 adult tigers. Despite these promising trends, Bhutan’s environment is under threat. Although the low population density of 13 people per square kilometer has protected the natural habitat from heavy encroachment and over-exploitation of its resources, the population growth rate is of great concern. -

Illegal Evictions from India's Tiger Reserves

For tribes, for nature, for all humanity Illegal evictions from India’s tiger reserves The officials from the reserve forced us to leave Subelal Dhurwey, Baiga tribe Evicted from Kanha Tiger Reserve, India 01 Illegal evictions from Indian Tiger Reserves Contents Introduction 02 What does national law say? 04 How is national law being violated? 06 Violations of international law and commitments 16 Involvement of international conservation organisations 17 Conclusion 18 References 20 02 Illegal evictions from Indian Tiger Reserves Introduction Tribal communities living in Indian tiger reserves are being We were one of the last families illegally evicted from their ancestral homelands in the name of to resist. But the officials from conservation. Tiger conservationists insist that these evictions the reserve forced us to leave. are “voluntary relocations” but as this legal analysis proves, in They told us they’d take care many cases they are forced and therefore illegal. of us for three years, but they didn’t do a thing. Even when my Over 100,000 people have already been removed from brother was killed, no one came protected areas in India.1 In 2016, the head of the National to help us Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) announced that almost Subelal Dhurwey, a young Baiga man 300,000 people, from over 700 villages, are also earmarked for whose brother, Sukhdev Dhurwey, was 2 murdered after being evicted relocation. A further three to four million people live inside India’s Kanha Tiger Reserve protected areas and wildlife corridors with the threat of eviction hanging over them.3 Millions more have been deprived fully or 4 partially of their sources of livelihood and survival. -

Reptile Diversity in an Amazing Tropical Environment: the West Indies - L

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT - Vol. VIII - Reptile Diversity In An Amazing Tropical Environment: The West Indies - L. Rodriguez Schettino REPTILE DIVERSITY IN AN AMAZING TROPICAL ENVIRONMENT: THE WEST INDIES L. Rodriguez Schettino Department of Zoology, Institute of Ecology and Systematics, Cuba To the memory of Ernest E. Williams and Austin Stanley Rand Keywords: Reptiles, West Indies, geographic distribution, morphological and ecological diversity, ecomorphology, threatens, conservation, Cuba Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reptile diversity 2.1. Morphology 2.2.Habitat 3. West Indian reptiles 3.1. Greater Antilles 3.2. Lesser Antilles 3.3. Bahamas 3.4. Cuba (as a study case) 3.4.1. The Species 3.4.2. Geographic and Ecological Distribution 3.4.3. Ecomorphology 3.4.4. Threats and Conservation 4. Conclusions Acknowledgments Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The main features that differentiate “reptiles” from amphibians are their dry scaled tegument andUNESCO their shelled amniotic eggs. In– modern EOLSS studies, birds are classified under the higher category named “Reptilia”, but the term “reptiles” used here does not include birds. One can externally identify at least, three groups of reptiles: turtles, crocodiles, and lizards and snakes. However, all of these three groups are made up by many species that are differentSAMPLE in some morphological characters CHAPTERS like number of scales, color, size, presence or absence of limbs. Also, the habitat use is quite variable; there are reptiles living in almost all the habitats of the Earth, but the majority of the species are only found in the tropical regions of the world. The West Indies is a region of special interest because of its tropical climate, the high number of species living on the islands, the high level of endemism, the high population densities of many species, and the recognized adaptive radiation that has occurred there in some genera, such as Anolis, Sphaerodactylus, and Tropidophis. -

Multinational Species Conservation Fund

FY 2009 BUDGET JUSTIFICATION MULTINATIONAL SPECIES CONSERVATION FUND Multinational Species Conservation Fund Appropriations Language For expenses necessary to carry out the African Elephant Conservation Act (16 U.S.C. 4201-4203, 4211- 4214, 4221-4225, 4241-4246, and 1538), the Asian Elephant Conservation Act of 1997 (16 U.S.C. 4261- 4266), the Rhinoceros and Tiger Conservation Act of 1994 (16 U.S.C. 5301-5306), the Great Ape Conservation Act of 2000 (16 U.S.C. 6301-6305), and the Marine Turtle Conservation Act of 2004 (16 U.S.C. 6601-6606), [$8,000,000]$4,256,000, to remain available until expended. (Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2008.) Authorizing Statutes African Elephant Conservation Act, (16 U.S.C. 4201-4203, 4211-4213, 4221-4225, 4242- 4245,1538). Authorizes funding for approved projects for research, conservation, management and protection of African elephants and their habitats. Authorizes prohibitions against the sale, importation, and exportation of ivory derived from African elephants. Authorization of Appropriations: Expires September 30, 2012. Asian Elephant Conservation Act, (16 U.S.C. 4261-4266, 1583). Authorizes financial assistance for cooperative projects for the conservation and protection of Asian elephants and their habitats. Authorization of Appropriations: Expires September 30, 2012. Rhinoceros and Tiger Conservation Act, (16. U.S.C. 5301-5306, 1583). Authorizes grants to other nations and to the CITES Secretariat for programs directly or indirectly assisting in the conservation of rhinoceros and tigers. Prohibits the sale, importation, and exportation of products derived from any species of rhinoceros and tiger. Authorization of Appropriations: Expires September 30, 2012. -

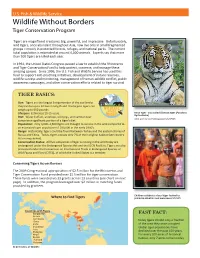

Wildlife Without Borders Tiger Conservation Program

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wildlife Without Borders Tiger Conservation Program Tigers are magnifi cent creatures: big, powerful, and impressive. Unfortunately, wild ti gers, once abundant throughout Asia, now live only in small fragmented groups – mostly in protected forests, refuges, and nati onal parks. The current total populati on is esti mated at around 4,000 animals. Experts say that more than 500 ti gers are killed each year. In 1994, the United States Congress passed a law to establish the Rhinoceros and Tiger Conservati on Fund to help protect, conserve, and manage these amazing species. Since 1996, the U.S. Fish and Wildife Service has used this fund to support anti -poaching initi ati ves, development of nature reserves, wildlife surveys and monitoring, management of human-wildlife confl ict, public awareness campaigns, and other conservati on eff orts related to ti ger survival. TIGER BASICS: Size: Tigers are the largest living member of the cat family; they can be up to 12 feet in length and the largest ti gers can weigh up to 650 pounds. Lifespan: Esti mated 10-15 years. Amur ti ger - also called Siberian ti ger (Panthera ti gris altaica) Diet: Water buff alo, antelope, wild pigs, and sambar deer John and Karen Hollingsworth/USFWS comprise a signifi cant porti on of a ti ger’s diet. Populati on: Only 3,000-4,500 ti gers are thought to survive in the wild compared to an esti mated ti ger populati on of 100,000 in the early 1900’s. Range: Historically, ti gers could be found between Turkey and the eastern shores of Russia and China. -

Global Tiger Day, 2020

Global Tiger Day, 2020 ENVIS RP on Geodiversity & Impact on Environment, School of Environmental Sciences, JNU celebrated the Global Tiger Day, 29th July 2020. A webinar was organized to celebrate Global Tiger Day. Time duration of the webinar was one hour. Panelists included international experts and professionals working in the field of Wildlife and Environment Conservation. These were- 1) Dr. G. Areendran, Director-IGCMC & Coordinator ENVIS , WWF, India, 2)Dr.K.Ramesh,Scientist, WII, India &Adjunct Professor, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, 3) Professor Umesh Kulshrestha, Dean SES, JNU and ENVIS-Coordinator, 4) Prof. P. K. Joshi, SES, JNU 5) Dr Usha Mina, Associate Professor JNU & Co-coordinator JNU ENVIS. Professor Umesh Kulshrestha, Dean SES, JNU and ENVIS-Coordinator moderated the panel discussion. It was attended by more than 200 participants, through Google-Meet platform and Facebook live broadcast. Also, the participants were from different parts of the country and included university students, researchers, faculty members and professionals. 1 Fig.1: Poster and Schedule of the Webinar widely circulated on JNU ENVIS Website & Social media platforms Prof. Umesh Kulshrestha, Dean & ENVIS Coordinator, SES, JNU - He welcomed all the eminent speakers and the participants. Gave a brief introduction of all the speakers. Highlighted the importance of the Global Tiger Day and Tiger as an important species for conservation of the whole ecosystem. According to the latest Tiger Census data released India has about 2964 Tigers. He then invited Dr.G.Areendran, Director-IGCMC & Coordinator ENVIS , WWF, India to deliver his talk. 2 Fig.2: Moderator of the Webinar: Prof. Umesh Kulshrestha, Dean & ENVIS Coordinator, SES, JNU & all speakers on the Panel. -

Media Release New-Look Tiger Island Opens At

MEDIA RELEASE Friday 16 September 2016 NEW-LOOK TIGER ISLAND OPENS AT DREAMWORLD THIS SUNDAY 18/9 Following a $7million transformation, the first stage of Dreamworld’s all-new Tiger Island will open to theme park guests from this Sunday (18/9). Officially launching the exhibit today, Queensland Minster for Tourism and Major Events, the Honourable Kate Jones MP, welcomed the new-look Tiger Island as a world-class, iconic attraction for Queensland. Ms Jones said Dreamworld’s new Tiger Island was a major new tourism drawcard for the Gold Coast. “This is a world class animal exhibit providing animal conservation through responsible tourism,” she said. “I congratulate Dreamworld for delivering on their vision combining tiger conservation and tourism development. This exhibit will attract more visitors to Dreamworld and the Gold Coast, supporting jobs and the local tourism economy.” Gold Coast Deputy Mayor, Councillor Donna Gates said the new Tiger Island would further position the city as a leading holiday destination that is constantly evolving with fresh new product to attract more visitors and keep them coming back again and again. Dreamworld CEO Craig Davidson said the reinvigoration of Tiger Island would ensure the park retained its leading role in the global race to save tigers in the wild. “The redevelopment of Tiger Island is a significant milestone for Dreamworld and a wonderful gift for our tigers and their wild cousins as we celebrate the 21st anniversary of Tiger Island,” said Mr Davidson. “Turning the spotlight on conservation, visitors to this amazing new conservation precinct will be able to feel closer to our tigers than ever before, encouraging empathy and educating guests on the plight of tigers in the wild. -

Restoring Island Biodiversity

Contents Mauritian reptiles Restoring island biodiversity: Mauritian reptiles Restoration and research the reintroduction of endemic Mauritian reptiles Skinks and geckos The Darwin Initiative project Dr Nicholas Cole University of Bristol Project protocol and timetable Dr Carl Jones Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Mauritian reptiles Mauritian reptiles Once one of the richest reptile diversities in the World This adaptive radiation caused the formation of a unique ecosystem In the absence of terrestrial mammals the reptiles evolved to occupy all available niches dependent upon reptiles Allowed adaptive radiation of: Tortoises Nocturnal and diurnal geckos Skinks Reptiles occupied all main functional Snakes groups: Mauritian reptiles Mauritian reptiles Predators: Prey: 1 Mauritian reptiles Mauritian reptiles Grazers and browsers: Seed dispersers: Mauritian reptiles Mauritian reptiles Pollinators: Human related disturbances over the past 400 years: Extensive habitat destruction Introduction of non-native predators and competitors More than 60% of reptile species lost from the main island through extinction or extirpation The majority of the extant species are now confined to offshore islands Mauritian reptiles Restoration and research Remaining island populations: Round Island Most intact reptile fauna of the Mascarenes Restricted and/or fragmented distributions Never invaded by predatory mammals or reptiles The loss of ecological links and food webs Habitat destruction caused