Children's Television Programming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TV Channel Lineup 607-589-6235

True TV Channel Lineup 607-589-6235 : www.htva.net Spencer East System – Barton, Candor, Halsey Valley, Smithboro, Spencer, Tioga, Weltonville, Willseyville, Lockwood v: 04302020 s Lifeline Tier Basic Tier (ctd.) Digital Tier (ctd) Digital Tier (ctd) High Def (ctd) Premium 3 WBGH NBC 3 Bing. 47 Lifetime 115 IFC 209 WSKG3 PBS Create 506 TBS HD 2 HBO 4 Local Ads 48 Animal Planet 116 TCM 210 WSKG4 PBS World 514 HLN HD 5 Cinemax 6 WICZ FOX 40 Bing. 49 Food Network 117 FX Movies 212 WENY3 CW 2 Elm. 515 CNN HD 98 HBO 2 7 WSKG PBS 46 Bing. 50 Comedy Central 118 Outdoor Channel 216 ESPNU 516 MSNBC HD 400 HBO SD 8 WENY2 CBS Elm. 51 HLN 119 The Golf Channel 223 Paramount 517 FOX News HD 401 HBO 2 SD 9 WIVT ABC 34 Bing. 52 CNN 120 FXX 261 VH1 521 Nick HD 402 HBO Signature 11 WBXI CW 11 Bing. 53 MSNBC 121 ESPN News 523 BIG10 Network HD 403 HBO Family 12 WBNG CBS 12 Bing. 54 FOX News 122 SEC Network 182High DefinitionWSPX Ion 56 HD 524 NFL Network HD* 404 HBO HD 13 WENY ABC 36 Elm. 55 CNBC 124 NFL Network 525 TNT HD 405 HBO 2 HD 14 WBPN MY 8 Bing. 56 Travel Channel 125 NBC Sports 182 WSPX ION 56 HD 527 Discovery HD 410 Cinemax SD 15 Weather Channel 57 VH1 126 RFD 185 WBXI CW 11 HD 528 CMT HD 411 MoMAX 17 Channel Guide 58 MTV 128 BBC World News 200 WBNG CBS 12HD 529 BBC America HD* 412 Cinemax HD 22 WSPX ION 56 Syr. -

Darien Cable TV

Darien Cable TV BASIC 2 WSAV - NBC 8 ION 14 C-Span 4 WJCL - ABC 9 WVAN - GPB 15 The Cowboy 5 Local Bulletin 10 WTGS - FOX Channel Board 11 BS T 16 QVC 6 Basic TV Guide 12 N WG 17 EWTN 7 WTOC - CBS 13 TBN 18 McIntosh Network EXPANDED BASIC 19 ESPN 38 E! 57 CMT Music 20 ESPN2 39 fyi, 58 MTV 21 ESPNews 40 truTV 59 VH1 22 ESPN Classic 41 Discovery 60 CNBC 23 Outdoor 42 Animal Planet 61 CNN Channel 43 TLC 62 HLN 24 Fox Sports 44 History 63 MSNBC South Channel 64 FOX News 25 Fox Sports 45 Food Network 65 The Weather Southeast 46 HGTV Channel 26 Fox Sports 1 47 Oxygen 66 Viceland 27 BET 48 Travel Channel 67 SEC Network 28 TNT 49 Syfy 68 Golf Channel 29 ID 50 Nickelodeon 69 Nat Geo 30 Hallmark 51 Cartoon 70 FXX Channel Network 71 AMC 31 USA 52 Disney 32 FX 53 Comedy Watch 33 Lifetime Central TVEverywhere 34 Freeform 54 OWN is FREE 35 TV Land 55 NBC Sports your cablewith 36 A&E Network 37 Bravo 56 Paramount TV subscription Customers must have a MOVIE PAKS digital set-top box to receive Movie Paks. HBO PACKAGE 225 SHO X BET 243 ActionMax 200 HBO HD** 226 Showtime 244 ThrillerMax 201 HBO Women 245 StarMax 202 HBO Comedy 227 Showtime Next 246 OuterMax 203 HBO Family 228 Showtime 247 MaxLT 204 HBO Plus Family Zone 229 The 205 HBO Signature Movie STARZ PACKAGE 206 HBO Zone Channel (TMC) 260 STARZ HD** 230 TMC Xtra 261 STARZ SHOWTIME/TMC 231 TMC HD** 262 STARZ InBlack PACKAGE 263 STARZ Kids & 220 Showtime HD** CINEMAX PACKAGE Family 221 Showtime 240 Cinemax HD** 264 STARZ Cinema 222 Showtime Too 241 Cinemax 265 STARZ Edge 223 Showtime 242 MoreMax Showcase 224 Showtime Extreme Cable installation charges may apply. -

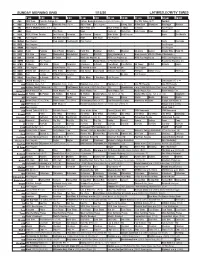

Sunday Morning Grid 1/12/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/12/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News College Basketball Michigan State at Purdue. (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å NBC4 News Paid Program Saving Pets A New Leaf Champion Bensinger Monster 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Hearts of Rock-Park Jack Hanna News Ocean Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Paid Program Fox News Sunday News The Issue Paid Program 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Christina Joanne Simply Ming Food 50 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Wunderkind Wunderkind Darwin’s Biz Kid$ Aging Backwards 3 Brain Secrets With Dr. Michael Merzenich Å 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Pathway Win Walk Prince Carpenter A Jackson In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Ed Young Bethel Kelinda Hagee 4 6 KFTR Paid Program Super Genios (TVY) El mundo es tuyo El mundo es tuyo Paid Program 5 0 KOCE Nature Cat Nature Cat Wild Kratts Wild Kratts Odd Squad Odd Squad Antiques Roadshow Antiques Nature (N) Å NOVA Å 5 2 KVEA Paid La Liga Fútbol Premier League La Liga Paid Program 5 6 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up Paid Cath. -

Cable/Coax Channel Line up 01/20/2020 Installer: ______Effective January 20, 2020 CSR: ______

01/20/2020 Cable/Coax Channel Line Up Installer: _______________ Effective January 20, 2020 CSR: _______________ Economy Package: Expanded Package: 3 ION 3 ION 42 A&E 4 KAIT2 NBC 4 KAIT2 NBC 43 Turner Classic Movies 5 KJNB2 CBS 5 KJNB2 CBS 44 Freeform 6 Local Access 6 Local Access 45 Lifetime 7 TV Guide/POP 7 TV Guide/POP 46 Hallmark 8 KAIT ABC 8 KAIT ABC 47 Bravo 9 Me TV/My Network 9 Me TV/My Network 48 TBS 10 VTN 10 VTN 49 TNT 11 Cozi TV 11 Cozi TV 50 FX 12 The Weather Channel 12 The Weather Channel 51 USA 13 KJNB FOX 13 KJNB FOX 52 Hallmark Movies/Mysteries 14 FoxSports Plus-Cardinals 14 FoxSports Plus-Cardinals 53 SEC Network 15 KTEJ AETN2 Create 15 KTEJ AETN2 Create 54 TV Land 16 Qubo 16 Qubo 55 Nickelodeon 17 ION Plus 17 ION Plus 56 Cartoon Network 18 Grit TV 18 Grit TV 57 Disney 19 KTEJ AETN 19 KTEJ AETN 58 CMT 20 Trinity Broadcasting 20 Trinity Broadcasting 59 Paramount 21 HSN 21 HSN 60 MTV 22 QVC 22 QVC 61 VH-1 23 KJOS CW Plus 23 KJOS CW Plus 62 Outdoor Channel 24 WKNO PBS 24 WKNO PBS 63 History Channel 25 HGTV 25 HGTV 64 TLC 26 GCT 26 GCT 65 Discovery 27 PHS 27 PHS 66 E! TV 96 CSPAN 28 Travel Channel 67 Tru TV 97 KTEJ AETN 3 29 National Geographic 68 SyFy 98 CSPAN 2 30 Animal Planet 69 Comedy Central 31 Fox News 70 Food Network 32 Fox Sports SW 71 FXX 33 ESPN 72 Fox Sports 1 34 ESPN 2 73 BBC America 35 ESPN News 74 Oxygen 36 ESPN Classic 75 NBC Sports Network 37 CNN 76 Family Entertainment TV 38 Headline News 77 Pursuit 39 CNBC 96 CSPAN 40 MSNBC 97 KTEJ AETN 3 41 AMC 98 CSPAN2 99 SEC 2 Economy and Expanded Subscribers: If your TV is Digital Ready, using the TV’s remote, choose MENU and CHANNEL SCAN to receive programming. -

Ccfiber TV Channel Lineup

CCFiber TV Channel Lineup Locals+ Expanded (cont'd) Stingray Music Premium Channels (cont'd) 2 WKRN (ABC) 134 Travel Channel Included within Ultimate Cinemax Package 4 WSMV (NBC) 140 Viceland 210 Adult Alternative 5 WTVF (CBS) 144 OWN 211 ALT Rock Classics 330 5StarMAX 6 WTVF 5+ 145 Oxygen 212 Americana 331 ActionMAX East 8 WNPT (PBS) 146 Bravo 213 Bluegrass 332 ActionMAX West 9 QVC 147 E! 214 Broadway 333 MaxLatino 10 QVC2 148 We TV 215 Chamber Music 334 Cinemax East 12 ION 149 Lifetime 216 Classic Masters 335 Cinemax West 14 Qubo 151 Lifetime Movie Network 217 Classic R&B Soul 336 MoreMAX East 17 WZTV (FOX) 153 Hallmark Channel 218 Classic Rock 337 MoreMAX West 19 EWTN 154 Hallmark Movie 219 Country Classics 338 MovieMAX 20 Shop HQ 155 Hallmark Drama 220 Dance Clubbin 339 OuterMAX 21 Inspiration 160 Nick Jr. 221 Easy Listening 340 ThrillerMAX East 22 TBN 161 Disney Channel 222 Eclectic Electronic 341 ThrillerMAX West 25 WPGD 164 Cartoon Network 223 Everything 80's 27 CSPAN 165 Discovery Family 224 Flashback 70's Starz Package 28 CSPAN 2 166 Universal Kids 225 Folk Roots 29 CSPAN 3 168 Nickelodeon 226 Gospel 360 Starz West 30 WNPX (ION) 189 TV Land 227 Groove Disco and Funk 361 Starz East 32 WUXP (MY TV) 190 MTV 228 Heavy Metal 362 Starz Kids East 35 Jewelry TV 191 MTV 2 229 Hip Hop 363 Starz Kids West 36 HSN 192 VH1 230 Hit List 364 Starz in Black West 37 HSN2 194 BET 231 Holiday Hits 365 Starz in Black East 38 WJFB (Shopping) 200 CMT 232 Hot Country 366 Starz Edge West 41 WHTN (CTN) Ultimate (Includes Locals+ & Expanded) 233 Jammin -

E02630506 Fiber Creative Templates Q2 2021 Spring Channel

Channel Listings for The Triangle All channels available in HD unless otherwise noted. Download the latest version at SD Channel available in SD only google.com/fiber/channels ES Spanish language channel As of Summer 2021, channels and channel listings are subject to change. Local A—C ESPNews 211 National Geographic 327 Channel C-SPAN 131 A&E 298 ESPNU 213 EWTN 456 NBC Sports Network 203 C-SPAN 2 132 ACC Network 221 ES ES NBC Universo 487 C-SPAN 3 133 AMC 288 EWTN en Espanol 497 NewsNation 303 Cary TV SD 142 American Heroes 340 Food Network 392 NFL Network 219 Durham Community 8 Channel FOX Business News 120 Channel Animal Planet 333 FOX Deportes ES 470 Nickelodeon 421 SD Durham Public Schools 144 Bally Sports Carolinas 204 FOX News Channel 119 Nick2 422 HSN 23 Bally Sports Southeast 205 FOX Sports 1 208 Nick Jr. 425 SD HSN2 24 BBC America 287 FOX Sports 2 209 Nick Music 362 NASA 321 BBC World News 112 Freeform 286 Nicktoons 423 QVC 25 BET 355 Fusion 105 O—T QVC2 26 BET Gospel SD 378 FX 282 RTN 10 Public Access SD 143 BET Her 356 FX Movie Channel 281 Olympic Channel 602 RTN 11 Government 141 BET Jams SD 363 FXX 283 OWN: Oprah Winfrey 334 Access SD BET Soul SD 369 FYI 299 Oxygen 404 RTN 18 Education SD 18 Boomerang 431 GAC: Great American 373 Paramount Network 341 SD SD Country POSITIV TV 453 RTN 22 Bulletin Board 140 Bravo 296 ES The North Carolina 78 BTN – Outer Territory 207 Galavision 467 Science Channel 331 Channel BTN2 623 Golf Channel 249 SEC Network 216 SD WFPXDT (Court TV) 21 BTN3 624 Hallmark Channel 291 SEC Overflow 617 SD WLFLDT -

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE All Programming Subject to Change Without Notice

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE All programming subject to change without notice. Visit www.mtco.com for current channel directory. ReStart TV available on ALL channels! Channel Directory Premium Channels A&E Network 525 Hallmark Drama 480 TLC 549 HBO ACC Network 472 Hallmark Movie & Mystery 586 TNT 521 HBO 600 AMC 571 HGTV 537 Travel Channel 573 HBO2 601 American Heroes Channel 527 History Channel 529 TruTV 522 HBO Comedy 603 Animal Planet 550 HSN 578 Turner Classic Movies 520 HBO Family 602 BBC America 572 IFC 544 TV Land 553 HBO Latino 606 BBC World 485 Inspiration 587 Universal Kids 466 HBO Signature 604 BET 575 Investigation Discovery 551 UNIVERSO 360 HBO Zone 605 BET Gospel 357 Jewelry TV 579 UP 321 BET Her 356 Lifetime Movie Network 538 USA Network 523 CINEMAX BET Jams 352 Lifetime Real Women 40 VH1 583 5StarMAX 613 BET Soul 355 Lifetime Television 539 Viceland 528 ActionMAX 609 Big Ten Network 564 LOGO 340 WBBM 2-CBS 2 501 Cinemax 607 Cinemáx 612 Big Ten Network Overflow 420 Marquee Network 560 WBBM Dabl 215 MoreMAX 608 Boomerang 462 MGM HD 479 WBBM Fave TV 216 MovieMAX 611 Bravo 541 Military History 339 WBBM Start TV 214 OuterMAX 614 Cartoon Network 530 Motor Trend Network 552 WCIU Decades TV 203 ThrillerMAX 610 CBS Sports Network 474 MSNBC 513 WCIU Heroes & Icons 227 CMT 584 MTV 581 WCIU MeTV 226 SHOWTIME CMT Music 358 MTV Classic 354 WCIU MeTV+ 228 FLIX 634 CNBC 512 MTV Live 489 WCIU The CW 10 506 Sho x BET 622 CNBC World 334 MTV Tr3s 350 WCIU The U 229 Sho2 (east) 628 CNN 510 MTV U 353 WCPX ION 38 507 Sho2 (west) 629 CNN Headline News -

Broadcast Television (1945, 1952) ………………………

Transformative Choices: A Review of 70 Years of FCC Decisions Sherille Ismail FCC Staff Working Paper 1 Federal Communications Commission Washington, DC 20554 October, 2010 FCC Staff Working Papers are intended to stimulate discussion and critical comment within the FCC, as well as outside the agency, on issues that may affect communications policy. The analyses and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the FCC, other Commission staff members, or any Commissioner. Given the preliminary character of some titles, it is advisable to check with the authors before quoting or referencing these working papers in other publications. Recent titles are listed at the end of this paper and all titles are available on the FCC website at http://www.fcc.gov/papers/. Abstract This paper presents a historical review of a series of pivotal FCC decisions that helped shape today’s communications landscape. These decisions generally involve the appearance of a new technology, communications device, or service. In many cases, they involve spectrum allocation or usage. Policymakers no doubt will draw their own conclusions, and may even disagree, about the lessons to be learned from studying the past decisions. From an academic perspective, however, a review of these decisions offers an opportunity to examine a commonly-asserted view that U.S. regulatory policies — particularly in aviation, trucking, and telecommunications — underwent a major change in the 1970s, from protecting incumbents to promoting competition. The paper therefore examines whether that general view is reflected in FCC policies. It finds that there have been several successful efforts by the FCC, before and after the 1970s, to promote new entrants, especially in the markets for commercial radio, cable television, telephone equipment, and direct broadcast satellites. -

Foreign Government-Sponsored Broadcast Programming

February 11, 2021 Foreign Government-Sponsored Broadcast Programming Overview Radio Sputnik, a subsidiary of the Russian government- Congress has enacted several laws to enable U.S. citizens financed Rossiya Segodnya International Information and the federal government to monitor attempts by foreign Agency, airs programming on radio stations in Washington, governments to influence public opinion on political DC, and Kansas City, MO. Rossiya Segodnya has contracts matters. Nevertheless, radio and television viewers may with two different U.S.-based entities to broadcast Radio have difficulty distinguishing programs financed and Sputnik’s programming. One entity is a radio station distributed by foreign governments or their agents. In licensee itself, while the other is an intermediary. DOJ has October 2020, the Federal Communications Commission directed each entity to register under FARA. Copies of the (FCC) proposed new requirements for broadcast radio and Rossiya Segodnya’s contracts with both entities are television stations to identify foreign government-provided available on both the FCC and DOJ websites. programming. FCC filings and a November 2015 report from the Reuters Statutory Background news agency indicate that China Radio International (CRI), For nearly 100 years, beginning with the passage of the an organization owned by the Chinese government, may Radio Act of 1927 (P.L. 69-632) and the Communications have agreements to transmit programming to 10 full-power Act of 1934 (P.L. 73-416), Congress has required broadcast U.S. radio stations, but independent verification is not stations to label content supplied and paid for by third readily available. parties so viewers and listeners can distinguish it from content created by the stations themselves (47 U.S.C. -

Optilink Channel Line-Up

OPTILINK CHANNEL LINE-UP Antenna Basic 2 WSB - TV - ABC (Atl) 6 OptiLink TV 10 WDNN - TV - IND 14 WELF - TV - TBN 3 WRCB - TV - NBC 7 WDSI - TV - FOX 11 WXIA - TV - NBC (Atl) 15 WTCI - TV - PBS 4 TBS 8 WNGH - PBS (GPTV) 12 WDEF - TV - CBS 16 Heartland 5 WAGA - TV - FOX (Atl) 9 WTVC - TV - ABC 13 WFLI - TV - CW Preferred Package Free Antenna Basic PLUS 13 Free HD Channels* HD Channels 18 Channel Guide 38 Disney XD 58 MSNBC 19 SEC 2 39 Disney Jr. 59 CSPAN 1 202 ABC HD* 248 Discovery HD 20 ESPN 40 Cartoon Network 61 truTV 203 NBC HD* 249 History HD 21 ESPN2 41 SportSouth 62 QVC 204 TBS HD* 250 TLC HD 22 ESPN News 42 National Geographic 63 Home Shopping Network 205 FOX HD* 251 Animal Planet HD 23 ESPN Classic 43 Bravo 65 Inspirational Network 207 WDSI HD* 257 CNBC HD 24 SEC Network 44 Food Network 67 Revolt TV 209 WTVC HD* 258 MSNBC HD 25 FOX Sports Net South 45 HGTV 69 Great American Country 212 CBS HD* 269 GAC HD 26 Golf Channel 46 A & E 70 E! Entertainment 213 CW HD* 270 E! Entertainment HD 27 Outdoor Channel 47 Travel Channel 71 Syfy Channel 28 FOX Sports 1 48 Discovery Channel 72 Comedy TV 215 PBS HD* 271 SyFy HD 29 NBC Sports Network 49 History Channel 73 FXX 216 Heartland HD* 273 FXX HD 30 USA 50 TLC 74 American Movie Classics 220 ESPN HD 274 AMC HD 31 TNT 51 Animal Planet 75 Lifetime Movie Network 221 ESPN2 HD 314 FOX Business Network 32 MAVTV 52 Antenna TV 76 Turner Classic Movies 224 SEC Network HD 330 AXS TV HD 33 FX 53 CNN 77 CNN Español 225 FOX Sports HD 347 Oxygen HD 34 ABC Family 54 FOX News Channel 78 Galavision 226 Golf HD -

Tv Guide Ukiah Ca

Tv guide ukiah ca Continue 12:00 p.m. 12:30 p.m. 1:00 p.m. 1:30 p.m. 2:00 p.m. 2:30 p.m. 3:30 p.m. 4:30 p.m. 5:30 p.m. 6:00 p.m. 6:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. P.M. 7:30 p.m. 5:30 p.m. 6:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. 8:00 p.m. 5:30 p.m. 6:30 p.m. 7.30pm 1.1.1 Hindi News 12:00 p.m. 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. 00pm English News 12.30 pmLocal programming to 1.30pmLocal programming Shipra's Kitchen 2.30pm Ancient Secrets with Dr Naram 3:00pm Stress Free Life 3.30pm Ask Dr Nandy 4:00pm Colours India 5:00pm to 5:30pm Evening Local Programming Big Picture 6.30pm Diya TV Dialogue 7:00pm English news 8:00pm KAXTD10 1.10 La Vida Christiana Con Marino 12:00pm Perseverando en la Doctrina 12.30pm La Gran comisi'n 1:00pm Chires Ser Sano? 1:30pm Preparaci'n finale 2:00pm Preparaci'n finale 2.30pm Programaci'n para ni'os 3:00pm Esta es tu hor 3.30pm Video musicals 4:00pm Cristiano Mundo 4.30pm Nuevas de Gran Gozo 5:00pm Pregunte al aboga 5:30pm 30pm Nuevas de Gran Gozo 5:00pm Pregunte al aboga 5.30pm Tiempo de revelaci'n 6:00pm Esta es tu hora 6.30pm Hombres y Mujeres de Fe 7.00pm Vida Dura 7.30pm Estableciendo el Rayno 8.0pm KAX D11 1.11 New Artisans Collection India Jewellery Show 11:00am New Jewellery Under $1.11 100 1:00 p.m. -

Sparta Channel Lineup

Optimum Premier Includes Optimum Select Optimum College Sports Pack Premium Channels Effective April 2021 79 UP HD 579 121 Fox College Sports Atlantic 344 Showtime Showcase 119 TVG Network 122 Fox College Sports Central 345 Showtime Women 320 HBO HD 570 123 Fox College Sports Pacific 346 Showtime Next 321 HBO Family 347 Showtime Family Zone Optimum Sports Pack 322 HBO Latino HD 662 348 Showtime West HD 671 Sparta 323 HBO2 HD 661 102 Fight Network HD 602 349 Showtime 2 West HD 672 324 HBO Signature 103 Game+ HD 614 350 Showtime Showcase West 325 HBO Comedy 105 World Fishing Network HD 617 351 The Movie Channel HD 573 Channel 326 HBO Zone 106 Sportsman Channel HD 618 352 The Movie Channel Xtra 327 HBO West HD 663 107 MavTV Motorsport Network HD 619 353 The Movie Channel West HD 675 Lineup 328 HBO2 West HD 664 108 Gol TV (English) 354 The Movie Channel Xtra West 329 HBO Family West 114 Willow 360 Starz Encore 330 HBO Signature West 116 NHL Network HD 616 361 Starz Encore Action + Broadcast Basic 340 Showtime HD 572 119 TVG Network 363 Starz Encore Black 341 Showtime Extreme 130 NFL Red Zone HD 601 365 Starz Encore Classic + Optimum Core 342 Showtime 2 HD 670 Premium Channels 367 Starz Encore Suspense + Optimum Select 343 SHOxBET 369 Starz Encore Westerns 344 Showtime Showcase 270 – 283 MLB Extra Innings (HD Only) 371 Starz Encore West + Optimum Premier 345 Showtime Women 270 – 283 NHL Center Ice (HD Only) 372 Starz Encore Family + Optimum Sports Pack 346 Showtime Next 320 HBO HD 570 373 Starz Encore Espanol + 347 Showtime Family Zone 321