Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHONICS INSTRUCTION in NEW BASAL READER PROGRAMS Dolores Durkin University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign February 1990

I L L NO I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Technical Report No. 496 PHONICS INSTRUCTION IN NEW BASAL READER PROGRAMS Dolores Durkin University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign February 1990 Center for the Study of Reading TECHNICAL ^ %>ok REPORTS C 0f lop. 4'ý ^- ^ UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 174 Children's Research Center 51 Gerty Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF READING Technical Report No. 496 PHONICS INSTRUCTION IN NEW BASAL READER PROGRAMS Dolores Durkin University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign February 1990 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 51 Gerty Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 The work upon which this publication was based was supported in part by the Office of Educational Research and Improvement under Cooperative Agreement No. G0087-C1001-90 with the Reading Research and Education Center. The publication does not necessarily reflect the views of the agency supporting the research. EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD 1989-90 James Armstrong Jihn-Chang Jehng Linda Asmussen Robert T. Jimenez Gerald Arnold Bonnie M. Kerr Yahaya Bello Paul W. Kerr Diane Bottomley Juan Moran Catherine Burnham Keisuke Ohtsuka Candace Clark Kathy Meyer Reimer Michelle Commeyras Hua Shu John M. Consalvi Anne Stallman Christopher Currie Marty Waggoner Irene-Anna Diakidoy Janelle Weinzierl Barbara Hancin Pamela Winsor Michael J. Jacobson Marsha Wise MANAGING EDITOR Fran Lehr MANUSCRIPT PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS Delores Plowman Debra Gough Durkin Phonics Instruction - 1 Abstract This report describes the results of an examination of five basal reader series, analyzed for the purpose of learning about the phonics instruction that each provides from kindergarten through Grade 6. -

Janet and John: Here We Go Free Download

JANET AND JOHN: HERE WE GO FREE DOWNLOAD Mabel O'Donnell,Rona Munro | 40 pages | 03 Sep 2007 | Summersdale Publishers | 9781840246131 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom Janet and John Series Toral Taank rated it it was amazing Nov 29, All of our paper waste is recycled and turned into corrugated cardboard. Doesn't post to Germany See details. Visit my eBay shop. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Shelves: beginner-readersfemale-author-or- illustrator. Hardcover40 pages. Reminiscing Read these as a child, Janet and John: Here We Go use with my Grandbabies X Previous image. Books by Mabel O'Donnell. No doubt, Janet and John: Here We Go critics will carp at the daringly minimalist plot and character de In a recent threadsome people stated their objections to literature which fails in its duty to be gender-balanced. Please enter a number less than or equal to Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Watch this item Unwatch. Novels portal Children's literature portal. Janet and John: Here We Go O'Donnell and Rona Munro. Ronne Randall. Learning to read. Inas part of a trend in publishing nostalgic facsimiles of old favourites, Summersdale Publishers reissued two of the original Janet and John books, Here We Go and Off to Play. Analytical phonics Basal reader Guided reading Independent reading Literature circle Phonics Reciprocal teaching Structured word inquiry Synthetic phonics Whole language. We offer great value books on a wide range of subjects and we have grown steadily to become one of the UK's leading retailers of second-hand books. -

Literacy in India: the Gender and Age Dimension

OCTOBER 2019 ISSUE NO. 322 Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension TANUSHREE CHANDRA ABSTRACT This brief examines the literacy landscape in India between 1987 and 2017, focusing on the gender gap in four age cohorts: children, youth, working-age adults, and the elderly. It finds that the gender gap in literacy has shrunk substantially for children and youth, but the gap for older adults and the elderly has seen little improvement. A state-level analysis of the gap reveals the same trend for most Indian states. The brief offers recommendations such as launching adult literacy programmes linked with skill development and vocational training, offering incentives such as employment and micro-credit, and leveraging technology such as mobile-learning to bolster adult education, especially for females. It underlines the importance of community participation for the success of these initiatives. Attribution: Tanushree Chandra, “Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension”, ORF Issue Brief No. 322, October 2019, Observer Research Foundation. Observer Research Foundation (ORF) is a public policy think tank that aims to influence the formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India. ORF pursues these goals by providing informed analyses and in-depth research, and organising events that serve as platforms for stimulating and productive discussions. ISBN 978-93-89622-04-1 © 2019 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, archived, retained or transmitted through print, speech or electronic media without prior written approval from ORF. Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension INTRODUCTION “neither in terms of absolute levels of literacy nor distributive justice, i.e., reduction in gender Literacy is one of the most essential indicators and caste disparities, does per capita income of the quality of a country’s human capital. -

Literacy UN Acked: What DO WE MEAN by Literacy?

Memo 4 | Fall 2012 LEAD FOR LITERACY MEMO Providing guidance for leaders dedicated to children's literacy development, birth to age 9 L U: W D W M L? The Issue: To make decisions that have a positive What Competencies Does a Reader Need to impact on children’s literacy outcomes, leaders need a Make Sense of This Passage? keen understanding of literacy itself. But literacy is a complex concept and there are many key HIGH-SPEED TRAINS* service that moved at misunderstandings about what, exactly, literacy is. A type of high-speed a speed of one train was first hundred miles per Unpacking Literacy Competencies hour. Today, similar In this memo we focus specifically on two broad introduced in Japan about forty years ago. Japanese trains are categories of literacy competencies: skills‐based even faster, traveling The train was low to competencies and knowledge‐based competencies. at speeds of almost the ground, and its two hundred miles nose looked somewhat per hour. There are like the nose of a jet. Literacy many reasons that These trains provided high-speed trains are Reading, Wring, Listening & Speaking the first passenger popular. * Passage adapted from Good & Kaminski (2007) Skills Knowledge Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, 6th ed. ‐ Concepts about print ‐ Concepts about the ‐ The ability to hear & world Map sounds onto letters (e.g., /s/ /p/ /ee/ /d/) work with spoken sounds ‐ The ability to and blend these to form a word (speed) ‐ Alphabet knowledge understand & express Based ‐ Word reading complex ideas ‐ Recognize -

Assessing the Lexile Framework: Results of a Panel Meeting

NATIONAL CENTER FOR EDUCATION STATISTICS Working Paper Series August 2001 The Working Paper Series was initiated to promote the sharing of the valuable work experience and knowledge reflected in these preliminary reports. These reports are viewed as works in progress, and have not undergone a rigorous review for consistency with NCES Statistical Standards prior to inclusion in the Working Paper Series. U.S. Department of Education Office of Educational Research and Improvement. NATIONAL CENTER FOR EDUCATION STATISTICS Working Paper Series Assessing the Lexile Framework: Results of a Panel Meeting Working Paper No. 2001-08 August 2001 Sheida White, Ph.D. Assessment Division National Center for Education Statistics John Clement, Ph.D. Education Statistics Services Institute U.S. Department of Education Office of Educational Research and Improvement. U.S. Department of Education Rod Paige Secretary Office of Educational Research and Improvement Grover J. Whitehurst Assistant Secretary National Center for Education Statistics Gary W. Phillips Acting Commissioner The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is the primary federal entity for collecting, analyzing and reporting data related to education in the United States and other nations. It fulfills a congressional mandate to collect, collate, analyze, and report full and complete statistics on the condition of education in the United States; conduct and publish reports and specialized analyses of the meaning and significance of such statistics; assist state and local education agencies in improving their statistical systems; and review and report on education activities in foreign countries. NCES activities are designed to address high priority education data needs; provide consistent, reliable, complete, and accurate indicators of education status and trends; and report timely, useful, and high quality data to the U.S. -

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet Written by Belinda Dekker Dyslexia Support Australia https://dekkerdyslexia.wordpress.com/ Structured Literacy • Structured literacy is a scientifically researched based approach to the teaching of reading. Structured literacy can be in the form of teachers trained in the use of structured literacy methodologies and programs that adhere to the fundamental and essential components of structured literacy. • Structure means that there is a step by step clearly defined systematic process to the teaching of reading. Including a set procedure for introducing, reviewing and practicing essential concepts. Concepts have a clearly defined sequence from simple to more complex. Each new concept builds upon previously introduced concepts. • Knowledge is cumulative and the program or teacher will use continuous assessment to guide a student’s progression to the next clearly defined step in the program. An important fundamental component is the automaticity of a concept before progression. • Skills are explicitly or directly taught to the student with clear explanations, examples and modelling of concepts. ‘The term “Structured Literacy” is not designed to replace Orton Gillingham, Multi-Sensory or other terms in common use. It is an umbrella term designed to describe all of the programs that teach reading in essentially the same way'. Hal Malchow. President, International Dyslexia Association A Position Statement on Approaches to Reading Instruction Supported by Learning Difficulties Australia "LDA supports approaches to reading instruction that adopt an explicit structured approach to the teaching of reading and are consistent with the scientific evidence as to how children learn to read and how best to teach them. -

Orton-Gillingham Or Multisensory Structured Language Approaches

JUST THE FACTS... Information provided by The International Dyslexia Association® ORTON-GILLINGHAM-BASED AND/OR MULTISENSORY STRUCTURED LANGUAGE APPROACHES The principles of instruction and content of a Syntax: Syntax is the set of principles that dictate the multisensory structured language program are essential sequence and function of words in a sentence in order for effective teaching methodologies. The International to convey meaning. This includes grammar, sentence Dyslexia Association (IDA) actively promotes effective variation, and the mechanics of language. teaching approaches and related clinical educational Semantics: Semantics is that aspect of language intervention strategies for dyslexics. concerned with meaning. The curriculum (from the beginning) must include instruction in the CONTENT: What Is Taught comprehension of written language. Phonology and Phonological Awareness: Phonology is the study of sounds and how they work within their environment. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound PRINCIPLES OF INSTRUCTION: How It Is Taught in a given language that can be recognized as being Simultaneous, Multisensory (VAKT): Teaching is distinct from other sounds in the language. done using all learning pathways in the brain Phonological awareness is the understanding of the (visual/auditory, kinesthetic-tactile) simultaneously in internal linguistic structure of words. An important order to enhance memory and learning. aspect of phonological awareness is phonemic awareness or the ability to segment words into their Systematic and Cumulative: Multisensory language component sounds. instruction requires that the organization of material follows the logical order of the language. The Sound-Symbol Association: This is the knowledge of sequence must begin with the easiest and most basic the various sounds in the English language and their elements and progress methodically to more difficult correspondence to the letters and combinations of material. -

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program The International Dyslexia Association identifies Structured Literacy as an effective instructional approach for meeting the needs of students who struggle with learning to read. Structured Literacy utilizes systematic, explicit instruction to teach decoding skills including phonology, sound-symbol association, syllable types, morphology, syntax, and semantics. Structured Literacy instruction has been around for over a century and is sometimes referred to as systematic reading instruction, phonics-based reading instruction, the Orton-Gillingham Approach, or synthetic phonics, among other names. The SIPPS (Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics, and Sight Words) program, developed by Dr. John Shefelbine, is a multilevel program that develops the word-recognition strategies and skills that enable students to become independent and confident readers and writers. Dr. Shefelbine’s research emphasizes systematic instruction, and in many ways parallels the Orton-Gillingham Approach. Structured Literacy The table below notes the elements of Structured Literacy aligned to the SIPPS program. Elements of Structured Literacy SIPPS Phonology Defined as the study of sound structure of spoken Phonological awareness activities appear in every words; includes rhyming, counting words in lesson in SIPPS Beginning, Extension, and Plus. spoken sentences, clapping syllables in spoken These activities begin with segmenting and words, and phonemic awareness (manipulation of blending, include rhyme, and increase in complexity sounds). to dropping and substituting phonemes. Sound-Symbol Association Defined as connecting sounds to print, including Spelling-sounds are explicitly taught throughout the blending and segmenting. This should occur two program. Sounds are taught in order of utility, which ways: visual to auditory (reading) and auditory to allows students to quickly begin to read connected visual (spelling). -

All Oral Reading Practice Is Not Equal Or How Can I Integrate Fluency Into My Classroom?

All Oral Reading Practice Is Not Equal or How Can I Integrate Fluency Into My Classroom? Melanie Kuhn Rutgers, Graduate School of Education Paula Schwanenflugel University of Georgia ABSTRACT This paper discusses fluency’s role in reading development and suggests ways of incorporating fluency instruction into the literacy curriculum through a range of oral reading approaches. It concentrates on two distinct groups of learners: students who are making the shift to fluent reading (generally second and third graders) and those who have experienced difficulty making this transition (usually in fourth grade and beyond). As such, it presents approaches that can supplement a given literacy curriculum as well as approaches that can serve as the basis of a shared reading program. This range of instructional methods should assist both groups of learners in making the transition from purposeful decoding and monotonous reading to automatic word recognition and the expressive rendering of text. Literacy Teaching and Learning Volume 11, Number 1 pages 1–20 Literacy Teaching and Learning Volume 11, Number 1 Becoming a skilled reader is a multifaceted process. As part of this process, it is essential that students learn to develop their background knowledge, phonemic awareness and letter-sound correspondences, build their vocabularies, construct meaning from text, and more (National Institute for Child Health and Human Development [NICHD] National Reading Panel Report, 2000; International Reading Association, 2002). Further, they must get to the point where they can do all of this simultaneously and automatically in what is called fluent reading. This article presents several effective approaches to oral reading instruction that will assist students in becoming fluent readers and will allow them to make the transition from purposeful decoding and monotonous reading to automatic word recognition and the expressive rendering of text. -

Popular Measurement 2

One Fish, Two Fish Ranch Measures Reading Best Benjamin D. Wright and A. Jackson Stenner Think of reading as the tree in Figure l . It has roots up nine different reading tests to prove the separate identities like oral comprehension and phonological awareness. As read- of his nine kinds. He gave his nine tests to hundreds of stu- ing ability grows, a trunk extends through grade school, high dents, analyzed their responses to prove his thesis, and reported school, and college branching at the top into specialized vo- that he had established nine kinds of reading . But when Louis cabularies. That single trunk is longer than many realize. It Thurstone reanalyzed Davis' data (1946), Thurstone showed grows quite straight and conclusively that Davis singular from first grade Figure 1 had no evidence of more through college. than one dimension of Reading has al- The Reading Tree reading . ways been the most re- searched topic in educa- Anchor Study - tion. There have been 1970s many studies of reading In the 1970s, ability, large and small, worry about national lit- local and national. When One eracy moved the U.S. gov the results of these stud- Dominant ernment to finance a na- ies are reviewed, one clear Factor tional Anchor Study Uae- picture emerges. Despite Defines get, 1973) . Fourteen dif- the 97 ways to test read- the Trunk ferent reading tests were ing ability, many decades administered to a great of empirical data docu- many children in order to ment definitively that no uncover the relationships Carrot, 1971 researcher has been able Bashaw-Rentz, 1975 among the 14 different to measure more than one DavWrhurstone, 1948 test scores Bormuth, 1988 . -

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: the Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C. (2018). Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy. OT Practice 23(15), 14–18. The Research: Occupational therapy interventions for visual processing skills were found to positively affect academic achievement and social participation. Key elements of intervention activities needed for progress include: fine motor activities, copying skills, gross motor activities, and a high level of cognitive interaction with completing activities. What is it? Visual information processing skills refers to “a group of visual cognitive skills used for extracting and organizing visual information from the environment and integrating this information with other sensory modalities and higher cognitive functions”. Visual information processing skills are divided into three components: visual spatial, visual analysis, and visual motor. Visual motor integration skills (i.e. eye-hand coordination) are related to an individual’s ability to combine visual information processing skills with fine motor or gross motor movement. Studies have found that visual motor integration is a component of reading skills in children in elementary school Specific Combination of Intervention Strategies Found to be Successful Fine motor activities ● Intervention activities: Manipulating small items (e.g., beads, coins); opening the thumb web space, separating the two sides of the hand; practicing finger isolation; -

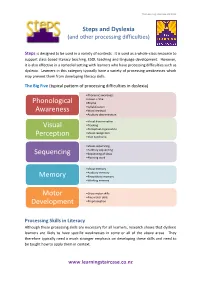

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word.