7 Carrie's Sisters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just How Nasty Were the Video Nasties? Identifying Contributors of the Video Nasty Moral Panic

Stephen Gerard Doheny Just how nasty were the video nasties? Identifying contributors of the video nasty moral panic in the 1980s DIPLOMA THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister der Philosophie Programme: Teacher Training Programme Subject: English Subject: Geography and Economics Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Evaluator Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jörg Helbig, M.A. Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Klagenfurt, May 2019 i Affidavit I hereby declare in lieu of an oath that - the submitted academic paper is entirely my own work and that no auxiliary materials have been used other than those indicated, - I have fully disclosed all assistance received from third parties during the process of writing the thesis, including any significant advice from supervisors, - any contents taken from the works of third parties or my own works that have been included either literally or in spirit have been appropriately marked and the respective source of the information has been clearly identified with precise bibliographical references (e.g. in footnotes), - to date, I have not submitted this paper to an examining authority either in Austria or abroad and that - when passing on copies of the academic thesis (e.g. in bound, printed or digital form), I will ensure that each copy is fully consistent with the submitted digital version. I understand that the digital version of the academic thesis submitted will be used for the purpose of conducting a plagiarism assessment. I am aware that a declaration contrary to the facts will have legal consequences. Stephen G. Doheny “m.p.” Köttmannsdorf: 1st May 2019 Dedication I I would like to dedicate this work to my wife and children, for their support and understanding over the last six years. -

From Sexploitation to Canuxploitation (Representations of Gender in the Canadian ‘Slasher’ Film)

Maple Syrup Gore: From Sexploitation to Canuxploitation (Representations of Gender in the Canadian ‘Slasher’ Film) by Agnieszka Mlynarz A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre Studies Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Agnieszka Mlynarz, April, 2017 ABSTRACT Maple Syrup Gore: From Sexploitation to Canuxploitation (Representations of Gender in the Canadian ‘Slasher’ Film) Agnieszka Mlynarz Advisor: University of Guelph, 2017 Professor Alan Filewod This thesis is an investigation of five Canadian genre films with female leads from the Tax Shelter era: The Pyx, Cannibal Girls, Black Christmas, Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS, and Death Weekend. It considers the complex space women occupy in the horror genre and explores if there are stylistic cultural differences in how gender is represented in Canadian horror. In examining variations in Canadian horror from other popular trends in horror cinema the thesis questions how normality is presented and wishes to differentiate Canuxploitation by defining who the threat is. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Paul Salmon and Dr. Alan Filewod. Alan, your understanding, support and above all trust in my offbeat work ethic and creative impulses has been invaluable to me over the years. Thank you. To my parents, who never once have discouraged any of my decisions surrounding my love of theatre and film, always helping me find my way back despite the tears and deep- seated fears. To the team at Black Fawn Distribution: Chad Archibald, CF Benner, Chris Giroux, and Gabriel Carrer who brought me back into the fold with open arms, hearts, and a cold beer. -

Re-Reading the Monstrous-Feminine : Art, Film, Feminism and Psychoanalysis Ebook

RE-READING THE MONSTROUS-FEMININE : ART, FILM, FEMINISM AND PSYCHOANALYSIS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicholas Chare | 268 pages | 18 Sep 2019 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9781138602946 | English | London, United Kingdom Re-reading the Monstrous-Feminine : Art, Film, Feminism and Psychoanalysis PDF Book More Details Creed challenges this view with a feminist psychoanalytic critique, discussing films such as Alien, I Spit on Your Grave and Psycho. Average rating 4. Name required. Proven Seller with Excellent Customer Service. Enlarge cover. This movement first reached success in the Pitcairn Islands, a British Overseas Territory in before reaching the United States in , and the United Kingdom in where women over thirty were only allowed to vote if in possession of property qualifications or were graduates of a university of the United Kingdom. Sign up Log in. In comparison, both films support the ideas of feminism as they depict women as more than the passive or lesser able figures that Freud and Darwin saw them as. EMBED for wordpress. Doctor of Philosophy University of Melbourne. Her argument that man fears woman as castrator, rather than as castrated, questions not only Freudian theories of sexual difference but existing theories of spectatorship and fetishism, providing a provocative re-reading of classical and contemporary film and theoretical texts. Physical description viii, p. The Bible, if read secularly, is our primal source of horror. The initial display of women as villains despite the little screen time will further allow understanding of the genre of monstrous feminine and the roles and depths allowed in it which may or may not have aided the feminist movement. -

Female Authorship in the Slumber Party Massacre Trilogy

FEMALE AUTHORSHIP IN THE SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE TRILOGY By LYNDSEY BROYLES Bachelor of Arts in English University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 2016 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2019 FEMALE AUTHORSHIP IN THE SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE TRILOGY Thesis Approved: Jeff Menne Thesis Adviser Graig Uhlin Lynn Lewis ii Name: LYNDSEY BROYLES Date of Degree: MAY, 2019 Title of Study: FEMALE AUTHORSHIP IN THE SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE TRILOGY Major Field: ENGLISH Abstract: The Slumber Party Massacre series is the only horror franchise exclusively written and directed by women. In a genre so closely associated with gender representation, especially misogynistic sexual violence against women, this franchise serves as a case study in an alternative female gaze applied to a notoriously problematic form of media. The series arose as a satire of the genre from an explicitly feminist lesbian source only to be mediated through the exploitation horror production model, which emphasized female nudity and violence. The resulting films both implicitly and explicitly address feminist themes such as lesbianism, trauma, sexuality, and abuse while adhering to misogynistic genre requirements. Each film offers a unique perspective on horror from a distinctly female viewpoint, alternately upholding and subverting the complex gender politics of women in horror films. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................1 -

Q & a with Stephanie Rothman

UCLA CSW Update Newsletter Title Q & A with Stephanie Rothman Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4jx713vz Author Sher, Ben Publication Date 2008-04-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California StephanieBY BEN SHER Rothman q&a with the director of The Velvet Vampire and The Student Nurses WITH Co-sponsorSHIP from the Center for the Study of Wom- en, The Crank, UCLA’s grad student run film society, recently hosted a special screening of writer-director Stephanie Roth- man’s acclaimed film The Velvet Vampire (1971) with the filmmaker in attendance. Rothman, writer-director of “exploitation” films like The Student Nurses (1970), Terminal Island (1973), and The Working Girls (1974) was one of the most prolific female filmmak- ers working in Hollywood in the 1970s. During that decade, her films were at the center of feminist debates concerning the most effective way in which women could use film to overturn Holly- wood’s often degrading representations. While some argued that the creation of avant-garde and independent films was the key to breaking the influence of the patriarchal system, others contend- ed that women working within the mainstream could dismantle and revise Hollywood representations to reveal and disempower their misogynistic qualities. Scholar Pam Cook wrote that “Rothman’s work was part of this polemic, since her films could be seen as a prime example of feminist subversion from within, using the generic formulae of exploitation cinema in the interest 1 of her own agenda as a woman director.” APR08 11 CSupdateW In her introduction to The Velvet Vampire, we were making films on a very low budget political opinions and we tried to make the Rothman stated that, “while in the Dracula for primarily drive-ins and older theaters in stories have more psychological depth. -

Marketing Swedish Crime Fiction in a Transnational Context

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies Title Uncovering a Cover: Marketing Swedish Crime Fiction in a Transnational Context Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6308x270 Journal Journal of Transnational American Studies, 7(1) Author Nilsson, Louise Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/T871030648 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SPECIAL FORUM Uncovering a Cover: Marketing Swedish Crime Fiction in a Transnational Context LOUISE NILSSON Key to the appeal of Scandinavian crime literature is the stoic nature of its detectives and their peculiarly close relationship with death. One conjures up a brooding Bergmanesque figure contemplating the long dark winter. [. .] Another narrative component just as vital is the often bleak Scandinavian landscape which serves to mirror the thoughts of the characters. ——Jeremy Megraw and Billy Rose, “A Cold Night’s Death: The Allure of Scandinavian Crime Fiction”1 The above quote from the New York Public Library’s website serves as a mise-en-place for introducing Scandinavian crime fiction by presenting the idea of the exotic, mysterious North. A headline on the website associates the phrase “A Cold Night’s Death” with the genre often called Nordic noir. A selection of Swedish book covers is on display, featuring hands dripping with blood, snow-covered fields spotted with red, and dark, gloomy forests. A close-up of an ax on one cover implies that there is a gruesome murder weapon. At a glance it is apparent that Scandinavian crime fiction is set in a winter landscape of death that nevertheless has a seductive allure. -

Proquest Dissertations

Juridically Minded, Justifiably Frightened: Academic Legitimacy and the Suspension of Horror Graeme Langdon A Thesis In the Department of Film Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2010 © Graeme Langdon, 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et ?F? Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-67155-9 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-67155-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Exploiting Exploitation Die Entwicklung des Exploitation-Genres und die Möglichkeit seiner weiblichen Aneignung Verfasserin Magdalena Eder angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Maga.Phil.) Wien, im September 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Thetaer-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuerin: Maga. Drin. Andrea B. Braidt, Mlitt 1 Einleitung..............................................................................................................6 1.1 Problemstellung und Zielsetzung..................................................................6 1.1.1 Vorgehensweise.....................................................................................10 2 Das Exploitationgenre.........................................................................................12 2.1 Einführung...................................................................................................12 2.2 60er und 70er: Filmhistorischer Hintergrund...........................................17 2.2.1 Produktion: Aus der Not eine Tugend.................................................21 2.2.2 Vermarktung: 'Gotta tell ´em to sell ´em'...........................................27 2.2.3 Darstellung: Frauen als Spektakel und Bedrohung...........................30 2.3 Space and Opportunity: Raum zur Aneignung..........................................39 2.3.1 A fine Line: Zwischen Kunst und Pornografie.....................................41 2.3.2 Sex durch Gewalt vs. -

Ow Video Arrow Arrow Video Arrow Vi Arrow Video

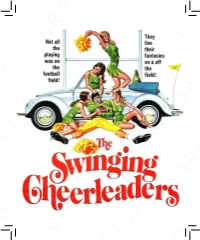

VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW ARROW VIDEO ARROW ARROW VIDEO 1 ARROW VIDEO ARROW ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW ARROW VIDEO ARROW ARROW VIDEO 2 ARROW VIDEO CONTENTS 4 7 Cast and Crew ARROW Pom Poms and Politics (2016) 20 by Cullen Gallagher About the Restoration ARROW 3 VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CAST AND CREW ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Ron HajekRainbeaux • Ric SmithCarrott • •Colleen Jason SommersCamp • Rosanne • Ian Sander Katon StarringA Jack Jo Johnston Hill Film ARROW ARROWalso starring VIDEO Jack Denton • John Quade • Bob Minor VIDEO with Mae Mercer And George Wallace director of photography ARROW Alfred Taylor, ARROW VIDEO edited by Mort Tubor William Castleman & Willam Loose A.R.P.S. music by Robinsonproduction Boyce designed& B.B. Neel by Jane Witherspoon & Betty Conkey ARROW VIDEOwritten by ARROW produced by John Prizer directed by Jack Hill ARROW VIDEO 4 ARROW VIDEO ARROW ARROW 5 VIDEO VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW POM POMS AND POLITICS VIDEO by Cullen Gallagher Romancing – and romanticising – the modern girl has been a preoccupation with American cinema from its inception. The first two decades of cinema saw numerous butterfly and serpentine dancers wiggling across the screen (and often these short films were hand- coloured to accentuate their alluring, scintillating, and fantastic qualities). The 1910s saw ARROW hordes of bathing beauties invading the screen (thank you, Mack Sennett); the 1920s had VIDEO their flappersVIDEO and vamps, while the 1930s had chorus girls and gold diggers; Betty Grable and other pin-ups inspired troops during the 1940s; beat girls, bombshells and femme fatales were the ‘it’ girls of the 1950s; and the 1960s began with beach babes and ended with The Stewardesses (1969). -

Developments in Revenge, Justice and Rape in the Cinema

Int J Semiot Law https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-019-09614-7 Developments in Revenge, Justice and Rape in the Cinema Peter W. G. Robson1 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract The index to the 2018 VideoHound Guide to Films suggests that under the broad heading of “revenge” there have been something in excess of 1000 flms. This appears to be the largest category in this comprehensive guide and suggests that this is, indeed, a theme which permeates the most infuential sector of popular cul- ture. These flms range from infuential and lauded flms with major directors and stars like John Ford (The Searchers (1956) and Alejandro González Iñárritu (The Revenant (2015)) to “straight to video” gorefests with little artistic merit and a spe- cifc target audience (The Hills Have Eyes (1977)). There is, as the Film Guide numbers suggest much in between like Straw Dogs (1972) and Outrage (1993). The making and re-making of “revenge” flms continues with contributions in 2018 from such major stars as Denzel Washington in The Equalizer 2 and Brue Willis in Death Wish. Within this body of flm is a roster of flms which allow us to speculate on the nature of the legal system and what individual and to a lesser extent commu- nity responses are likely where there appears to be a defcit of justice. One of the sub-groups within the revenge roster is a set of flms which focus on revenge by the victim for rape which are discussed for their rather diferent approach to the issue of justice. -

The Rhetoric of Rape-Revenge Films

THE RHETORIC OF RAPE-REVENGE FILMS: ANALYZING VIOLENT FEMALE PORTRAYALS IN MEDIA FROM A NARRATIVE PERSPECTIVE OF STANDPOINT FEMINISM Rachel Jean Turner Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of Communication Studies, Indiana University September 2018 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master's Thesis Committee ______________________________________ Catherine A. Dobris, Ph.D., Chair ______________________________________ Jennifer J. Bute, Ph.D. ______________________________________ Krista Hoffmann-Longtin, Ph.D. ii © 2018 Rachel Jean Turner iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my husband, three children, mother, father, three younger brothers, and best friend Mysty. But most of all, to God, who I know I would not have had the grace to make it this far without. I thank my husband for the inspiration he gave me to be true to myself. My three children I give thanks to for giving me a reason to keep going when I just wanted to give up. I am also immensely grateful to my mom for instilling values in me that helped to make the concepts taught in academia much easier to understand. To my dad, I give you thanks for giving me a shoulder to cry on. Thank you to my three younger brothers for being my competition. To Mysty, I dedicate this thesis to you for the curiosity and inspiration you ignited within me in the first place. And finally, God, thank you for being my rock and my salvation.