7 Conversation a Skill for the Culturally Proficient Leader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Working with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Communication & Social Skill Challenges Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist Consultant for Autism Spectrum Disorders [email protected] Learning effective conversation skills ranks as one of the most significant social abilities that students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) need to accomplish. Educators and parents list the challenges: “Steve talks too much.” “Shannon doesn’t take her turn.” “Aiden talks when no one is listening.” “Brandon perseverates on inappropriate topics.” “Kim doesn’t respond when people try to communicate with her.” The list goes on and on. Difficulty with conversation prevents these students from successfully taking part in social opportunities. What makes learning conversation skills so difficult? Conversation requires exactly the skills these students have difficulty with, such as: • Attending • Quickly taking in and processing information • Interpreting confusing social cues • Understanding vocabulary • Comprehending abstract language Many of those skills that create skillful conversation are just the ones that are difficult as a result of the core deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Think about it. From the student’s point of view, conversation can be very puzzling. Conversation is dynamic. .fleeting. .changing. .unpredictable. © Linda Hodgdon, 2007 1 All Rights Reserved This article may not be duplicated, -

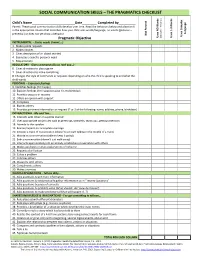

Social Communication Skills – the Pragmatics Checklist

SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS – THE PRAGMATICS CHECKLIST Child’s Name Date .Completed by . Words Preverbal) Parent: These social communication skills develop over time. Read the behaviors below and place an X - 3 in the appropriate column that describes how your child uses words/language, no words (gestures – - Language preverbal) or does not yet show a behavior. Present Not Uses Complex Uses Complex Gestures Uses Words NO Uses 1 Pragmatic Objective ( INSTRUMENTAL – States needs (I want….) 1. Makes polite requests 2. Makes choices 3. Gives description of an object wanted 4. Expresses a specific personal need 5. Requests help REGULATORY - Gives commands (Do as I tell you…) 6. Gives directions to play a game 7. Gives directions to make something 8. Changes the style of commands or requests depending on who the child is speaking to and what the child wants PERSONAL – Expresses feelings 9. Identifies feelings (I’m happy.) 10. Explains feelings (I’m happy because it’s my birthday) 11. Provides excuses or reasons 12. Offers an opinion with support 13. Complains 14. Blames others 15. Provides pertinent information on request (2 or 3 of the following: name, address, phone, birthdate) INTERACTIONAL - Me and You… 16. Interacts with others in a polite manner 17. Uses appropriate social rules such as greetings, farewells, thank you, getting attention 18. Attends to the speaker 19. Revises/repairs an incomplete message 20. Initiates a topic of conversation (doesn’t just start talking in the middle of a topic) 21. Maintains a conversation (able to keep it going) 22. Ends a conversation (doesn’t just walk away) 23. -

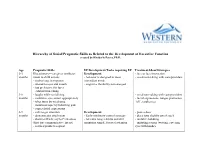

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

A Communication Aid Which Models Conversational Patterns

A communication aid which models conversational patterns. Norman Alm, Alan F. Newell & John L. Arnott. Published in: Proc. of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ‘87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. A communication aid which models conversational patterns Norman ALM*, Alan F. NEWELL and John L. ARNOTT University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, U.K. The research reported here was published in: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Conference on Rehabilitation Technology (RESNA ’87), San Jose, California, USA, 19-23 June 1987, pp. 127-129. The RESNA (Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America) site is at: http://www.resna.org/ Abstract: We have developed a prototype communication system that helps non-speakers to perform communication acts competently, rather than concentrating on improving the production efficiency for specific letters, words or phrases. The system, called CHAT, is based on patterns which are found in normal unconstrained dialogue. It contains information about the present conversational move, the next likely move, the person being addressed, and the mood of the interaction. The system can move automatically through a dialogue, or can offer the user a selection of conversational moves on the basis of single keystrokes. The increased communication speed which is thus offered can significantly improve both the flow of the conversation and the disabled person’s control of the dialogue. * Corresponding author: Dr. N. Alm, University of Dundee, Dundee DD1 4HN, Scotland, UK. A communication aid which models conversational patterns INTRODUCTION The slow rate of communication of people using communication aids is a crucial problem. -

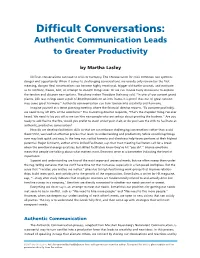

Difficult Conversations: Authentic Communication Leads to Greater Productivity

Difficult Conversations: Authentic Communication Leads to Greater Productivity by Martha Lasley Difficult conversations can lead to crisis or harmony. The Chinese word for crisis combines two symbols: danger and opportunity. When it comes to challenging conversations, we usually only remember the first meaning, danger. Real conversations can become highly emotional, trigger old battle wounds, and motivate us to confront, freeze, bolt, or attempt to smooth things over. Or we can choose lively discussions to explore the tension and discover new options. The piano maker Theodore Steinway said, “In one of our concert grand pianos, 243 taut strings exert a pull of 40,000 pounds on an iron frame. It is proof that out of great tension may come great harmony.” Authentic communication can turn tension into creativity and harmony. Imagine yourself at a tense planning meeting where the financial director reports, “To compete profitably, we need to lay off 20% of the workforce.” The marketing director responds, “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard. We need to lay you off so we can hire new people who are serious about growing the business.” Are you ready to add fuel to the fire, would you prefer to crawl under your chair, or do you have the skills to facilitate an authentic, productive conversation? How do we develop facilitation skills so that we can embrace challenging conversations rather than avoid them? First, we need an effective process that leads to understanding and productivity. While smoothing things over may look quick and easy, in the long run, radical honesty and directness help teams perform at their highest potential. -

How We Talk About How We Talk: Communication Theory in the Public Interest by Robert T

20042004 ICA ICAPresidential Presidential Address Address How We Talk About How We Talk: Communication Theory in the Public Interest by Robert T. Craig This article is a revision of the author’s presidential address to the 54th annual conference of the International Communication Association, presented May 29, 2004, in New Orleans, Louisiana. Using recent public discourse on talk and drugs as an example, it reflects on our culture’s preoccupation with communication and the pervasiveness of metadiscourse (talk about talk for practical purposes) in pri- vate, public, and academic discourses. It argues that communication theory can be used to describe and analyze the common vocabularies of public metadiscourse, critique assumptions about communication embedded in those vocabularies, and contribute useful new ways of talking about talk in the public interest. “Talk to your kids.” “Talk to your kids about drugs.” “Talk to your doctor.” “Talk to your doctor about Ambien.” “Ask you doctor if Lipitor is right for you.” “Ask your doctor if Advair is right for you.” “Talk. Know. Ask.” “Questions: The antidrug.” This collage of quotations selected from recent drug company commercials and antidrug public service announcements highlights a well-known irony in the pub- lic discourse on drugs that is not, however, my main point. Yes, the culture that produced these ads is rather obsessed with drugs. That culture is also rather obsessed with talk or, more generally, with communication. Both obsessions are on display in these ads in interesting juxtaposition. Drugs, in this cultural logic, are powerful and therefore as dangerous as they are desirable. They solve problems and they cause problems. -

Obtaining Contents of Communications

2013 ORS 165.5401 Obtaining contents of communications (1) Except as otherwise provided in ORS 133.724 (Order for interception of communications) or 133.726 (interception of oral communication without order) or subsections (2) to (7) of this section, a person may not: (a) Obtain or attempt to obtain the whole or any part of a telecommunication or a radio communication to which the person is not a participant, by means of any device, contrivance, machine or apparatus, whether electrical, mechanical, manual or otherwise, unless consent is given by at least one participant. (b) Tamper with the wires, connections, boxes, fuses, circuits, lines or any other equipment or facilities of a telecommunication or radio communication company over which messages are transmitted, with the intent to obtain unlawfully the contents of a telecommunication or radio communication to which the person is not a participant. (c) Obtain or attempt to obtain the whole or any part of a conversation by means of any device, contrivance, machine or apparatus, whether electrical, mechanical, manual or otherwise, if not all participants in the conversation are specifically informed that their conversation is being obtained. (d) Obtain the whole or any part of a conversation, telecommunication or radio communication from any person, while knowing or having good reason to believe that the conversation, telecommunication or radio communication was initially obtained in a manner prohibited by this section. (e) Use or attempt to use, or divulge to others, any conversation, telecommunication or radio communication obtained by any means prohibited by this section. (2) (a) The prohibitions in subsection (1 )(a), (b) and (c) of this section do not apply to: (A) Officers, employees or agents of a telecommunication or radio communication company who perform the acts prohibited by subsection (1 )(a), (b) and (c) of this section for the purpose of construction, maintenance or conducting of their telecommunication or radio communication service, facilities or equipment. -

Foundational Skills for Science Communication

Foundational Skills for Science Communication A Preliminary Framework Elyse L. Aurbach, PhD Public Engagement Lead Office of Academic Innovation, University of Michigan Katherine E. Prater, PhD Research Fellow University of Washington Emily T. Cloyd, MPS Director for the Center for Public Engagement with Science and Technology American Association for the Advancement of Science Laura Lindenfeld, PhD Executive Director for the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science Stony Brook University Abstract In order to work towards greater coherence across different training approaches supporting science communication and public engagement efforts, we present a preliminary framework that outlines foundational science communication skills. This framework categorizes different skills and their component parts and includes: identifying and aligning engagement goals; adapting to communication landscape and audience; messaging; language; narrative; design; nonverbal communication; writing style; and providing space for dialogue. Through this framework and associated Practical, research, and evaluative literatures, we aim to support the training community to explore more concretely opportunities that bridge research and Practice and to collectively discuss core competencies in science communication and public engagement. Introduction At a 2017 workshoP on “SuPPort Systems for Scientists’ Public Engagement: Communication Training,” and the 2018 Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, John Besley and Anthony Dudo referred to the current training landscaPe suPPorting science communication and Public engagement as the “Wild West.” Having comPleted a series of interviews with North American organizations focused on training scientists to effectively communicate and engage, they observed that while there were similar themes as to content, there was a great deal of variation in the aPProach, specific content, and teaching philosophy that different organizations used to teach communication skills and motivate engagement. -

Conversation with Noam Chomsky About Social Justice and the Future Chris Steele Master of Arts Candidate, Regis University, [email protected]

Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal Volume 1 | Number 2 Article 4 1-1-2012 Conversation with Noam Chomsky about Social Justice and the Future Chris Steele Master of Arts Candidate, Regis University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe Recommended Citation Steele, Chris (2012) "Conversation with Noam Chomsky about Social Justice and the Future," Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal: Vol. 1 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe/vol1/iss2/4 This Scholarship is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Steele: Conversation with Noam Chomsky Conversation with Noam Chomsky about Social Justice and the Future Chris Steele Master of Arts Candidate, Regis University ([email protected]) with Noam Chomsky Abstract Leading intellectual Noam Chomsky offers historical perspectives, insight and critique regarding recent social movements. His views on the Occupy movement, in particular, resonate with some key themes in Jesuit higher education. An interview with Chomsky, conducted by Chris Steele, centers on seven questions, presented here in both text and video, that can be used to spark reflection and discussion in university classrooms. Introduction including the Sydney Peace Prize in 2011 and honorary degrees from universities all around the The Jesuit tradition centers on engagement with world. In 2012 he received the Latin America the real world.1 Important developments and Peace and Justice Award from the North movements in the world such as the Arab Spring,2 American Congress on Latin America (NACLA).9 the Tea Party,3 and the Occupy Movement,4 to Perhaps, then, his is an important voice to hear in name a few, require deep discussion and conversations on some key themes in Jesuit higher understanding. -

Outline of Communication

Outline of communication The following outline is provided as an overview of and 2.1.2 Types of communication by mode topical guide to communication: • Conversation Communication – purposeful activity of exchanging in- formation and meaning across space and time using vari- • Mail ous technical or natural means, whichever is available or preferred. Communication requires a sender, a message, • Mass media a medium and a recipient, although the receiver does not • Book have to be present or aware of the sender’s intent to com- municate at the time of communication; thus communi- • Film cation can occur across vast distances in time and space. • Journalism • News media • Newspaper 1 Essence of communication • Technical writing • Video • Communication theory • Telecommunication (outline) • Development communication • Morse Code • Information • Radio • Telephone • Information theory • Television • Semiotics • Internet • Verbal communication 2 Branches of communication • Writing 2.1 Types of communication 2.2 Fields of communication 2.1.1 Types of communication by scope • Communication studies • Cognitive linguistics • Computer-mediated communication • Conversation analysis • Health communication • Crisis communication • Intercultural communication • Discourse analysis • International communication • Environmental communication • • Interpersonal communication Interpersonal communication • Linguistics • Intrapersonal communication • Mass communication • Mass communication • Mediated cross-border communication • Nonverbal communication • Organizational -

The Filipinos and the Philippines in Nora Cruz Quebral’S Development Communication Discourse: Strengthening Communication’S Groundedness in a Nation’S Context

IJAPS, Vol. 15, No. 2, 143–173, 2019 THE FILIPINOS AND THE PHILIPPINES IN NORA CRUZ QUEBRAL’S DEVELOPMENT COMMUNICATION DISCOURSE: STRENGTHENING COMMUNICATION’S GROUNDEDNESS IN A NATION’S CONTEXT Romel A. Daya* College of Development Communication, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines 4031 E-mail: [email protected] Published online: 15 July 2019 To cite this article: Daya, R. A. 2019. The Filipinos and the Philippines in Nora Cruz Quebral’s development communication discourse: Strengthening communication’s groundedness in a nation’s context. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies 15 (2): 143–173, https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2019.15.2.6 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2019.15.2.6 ABSTRACT The very first definition of development communication (DevCom) was articulated in 1971 by Nora Cruz Quebral. Since then, DevCom has continually flourished in the Philippines and its Asian neighbours as a field of study and practice. Quebral, a Filipina, is now widely recognised as one of the pillars and leading scholars of DevCom in Asia and the whole world. But how exactly has Quebral invested the Filipinos and the Philippines with meanings in her discourse of DevCom as a field of study and practice purportedly grounded in the context of developing nations and communities, and what are its implications? Informed and guided by Laclau and Mouffe’s Theory of Discourse, this paper identifies Quebral’s key articulations of DevCom, the Filipinos and the Philippines in her discourse, and discusses some implications of the discourse for the scholarship and practice of DevCom. -

A First Look at Communication Theory

gri34307_ch04_037-050.indd Page 37 1/3/11 8:44 AM user-f469 /Volumes/208/MHSF234/gri34307_disk1of1/0073534307/gri34307_pagefiles/Volumes/208/MHSF234/gri34307_disk1of1/0073534307/gri34307_pagefile CHAPTER 4 Mapping the Territory (Seven Traditions in the Field of Communication Theory) In Chapter 1, I presented working defi nitions for the concepts ofcommunication and theory . In Chapters 2 and 3, I outlined the basic differences between objective and interpretive communication theories. These distinctions should help bring order out of chaos when your study of theory seems confusing. And it may seem confusing. University of Colorado communication professor Robert Craig describes the fi eld of communication theory as awash with hundreds of unre- lated theories that differ in starting point, method, and conclusion. He suggests that our fi eld of study resembles “a pest control device called the Roach Motel that used to be advertised on TV: Theories check in, but they never check out.” 1 My mind conjures up a different image when I try to make sense of the often baffl ing landscape of communication theory. I picture a scene from the fi lm Raid- ers of the Lost Ark in which college professor Indiana Jones is lowered into a dark vault and confronts a thick layer of writhing serpents covering the fl oor—a tan- gle of communication theories. The intrepid adventurer discovers that the snakes momentarily retreat from the bright light of his torch, letting him secure a safe place to stand. It’s my hope that the core ideas of Chapters 1–3 will provide you with that kind of space.