Application to Tax-Exempt Financing Interest Rate Swaps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incentives for Central Clearing and the Evolution of Otc Derivatives

INCENTIVES FOR CENTRAL CLEARING AND THE EVOLUTION OF OTC DERIVATIVES – [email protected] A CCP12 5F No.55 Yuanmingyuan Rd. Huangpu District, Shanghai, China REPORT February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................... 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................. 5 1. MARKET OVERVIEW ............................................................................................. 8 1.1 CENTRAL CLEARING RATES OF OUTSTANDING TRADES ..................... 8 1.2 MARKET STRUCTURE – COMPRESSION AND BACKLOADING ............... 9 1.3 CURRENT CLEARING RATES ................................................................... 11 1.4 INITIAL MARGIN HELD AT CCPS .............................................................. 16 1.5 UNCLEARED MARKETS ............................................................................ 17 1.5.1 FX OPTIONS ...................................................................................... 18 1.5.2 SWAPTIONS ...................................................................................... 19 1.5.3 EUROPE ............................................................................................ 21 2. TRADE PROCESSING ......................................................................................... 23 2.1 TRADE PROCESSING OF NON-CLEARED TRADES ............................... 23 2.1.1 CUSTODIAL ARRANGEMENTS ....................................................... -

Section 1256 and Foreign Currency Derivatives

Section 1256 and Foreign Currency Derivatives Viva Hammer1 Mark-to-market taxation was considered “a fundamental departure from the concept of income realization in the U.S. tax law”2 when it was introduced in 1981. Congress was only game to propose the concept because of rampant “straddle” shelters that were undermining the U.S. tax system and commodities derivatives markets. Early in tax history, the Supreme Court articulated the realization principle as a Constitutional limitation on Congress’ taxing power. But in 1981, lawmakers makers felt confident imposing mark-to-market on exchange traded futures contracts because of the exchanges’ system of variation margin. However, when in 1982 non-exchange foreign currency traders asked to come within the ambit of mark-to-market taxation, Congress acceded to their demands even though this market had no equivalent to variation margin. This opportunistic rather than policy-driven history has spawned a great debate amongst tax practitioners as to the scope of the mark-to-market rule governing foreign currency contracts. Several recent cases have added fuel to the debate. The Straddle Shelters of the 1970s Straddle shelters were developed to exploit several structural flaws in the U.S. tax system: (1) the vast gulf between ordinary income tax rate (maximum 70%) and long term capital gain rate (28%), (2) the arbitrary distinction between capital gain and ordinary income, making it relatively easy to convert one to the other, and (3) the non- economic tax treatment of derivative contracts. Straddle shelters were so pervasive that in 1978 it was estimated that more than 75% of the open interest in silver futures were entered into to accommodate tax straddles and demand for U.S. -

Interest Rate Options

Interest Rate Options Saurav Sen April 2001 Contents 1. Caps and Floors 2 1.1. Defintions . 2 1.2. Plain Vanilla Caps . 2 1.2.1. Caplets . 3 1.2.2. Caps . 4 1.2.3. Bootstrapping the Forward Volatility Curve . 4 1.2.4. Caplet as a Put Option on a Zero-Coupon Bond . 5 1.2.5. Hedging Caps . 6 1.3. Floors . 7 1.3.1. Pricing and Hedging . 7 1.3.2. Put-Call Parity . 7 1.3.3. At-the-money (ATM) Caps and Floors . 7 1.4. Digital Caps . 8 1.4.1. Pricing . 8 1.4.2. Hedging . 8 1.5. Other Exotic Caps and Floors . 9 1.5.1. Knock-In Caps . 9 1.5.2. LIBOR Reset Caps . 9 1.5.3. Auto Caps . 9 1.5.4. Chooser Caps . 9 1.5.5. CMS Caps and Floors . 9 2. Swap Options 10 2.1. Swaps: A Brief Review of Essentials . 10 2.2. Swaptions . 11 2.2.1. Definitions . 11 2.2.2. Payoff Structure . 11 2.2.3. Pricing . 12 2.2.4. Put-Call Parity and Moneyness for Swaptions . 13 2.2.5. Hedging . 13 2.3. Constant Maturity Swaps . 13 2.3.1. Definition . 13 2.3.2. Pricing . 14 1 2.3.3. Approximate CMS Convexity Correction . 14 2.3.4. Pricing (continued) . 15 2.3.5. CMS Summary . 15 2.4. Other Swap Options . 16 2.4.1. LIBOR in Arrears Swaps . 16 2.4.2. Bermudan Swaptions . 16 2.4.3. Hybrid Structures . 17 Appendix: The Black Model 17 A.1. -

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: Analysing the Super-Senior Swap Element

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: analysing the Super-Senior Swap element Nicoletta Baldini * July 2003 Basic Facts In a typical cash flow securitization a SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) transfers interest income and principal repayments from a portfolio of risky assets, the so called asset pool, to a prioritized set of tranches. The level of credit exposure of every single tranche depends upon its level of subordination: so, the junior tranche will be the first to bear the effect of a credit deterioration of the asset pool, and senior tranches the last. The asset pool can be made up by either any type of debt instrument, mainly bonds or bank loans, or Credit Default Swaps (CDS) in which the SPV sells protection1. When the asset pool is made up solely of CDS contracts we talk of ‘synthetic’ Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs); in the so called ‘semi-synthetic’ CDOs, instead, the asset pool is made up by both debt instruments and CDS contracts. The tranches backed by the asset pool can be funded or not, depending upon the fact that the final investor purchases a true debt instrument (note) or a mere synthetic credit exposure. Generally, when the asset pool is constituted by debt instruments, the SPV issues notes (usually divided in more tranches) which are sold to the final investor; in synthetic CDOs, instead, tranches are represented by basket CDSs with which the final investor sells protection to the SPV. In any case all the tranches can be interpreted as percentile basket credit derivatives and their degree of subordination determines the percentiles of the asset pool loss distribution concerning them It is not unusual to find both funded and unfunded tranches within the same securitisation: this is the case for synthetic CDOs (but the same could occur with semi-synthetic CDOs) in which notes are issued and the raised cash is invested in risk free bonds that serve as collateral. -

Understanding Swap Spread.Pdf

Understanding and modelling swap spreads By Fabio Cortes of the Bank’s Foreign Exchange Division. Interest rate swap agreements were developed for the transfer of interest rate risk. Volumes have grown rapidly in recent years and now the swap market not only fulfils this purpose, but is also used to extract information about market expectations and to provide benchmark rates against which to compare returns on fixed-income securities such as corporate and government bonds. This article explains what swaps are; what information might be extracted from them; and what appear to have been the main drivers of swap spreads in recent years. Some quantitative relationships are explored using ten-year swap spreads in the United States and the United Kingdom as examples. Introduction priced efficiently at all times, swap spreads may be altered by perceptions of the economic outlook and A swap is an agreement between two parties to exchange supply and demand imbalances in both the swap and cash flows in the future. The most common type of the government bond markets. interest rate swap is a ‘plain vanilla fixed-for-floating’ interest rate swap(1) where one party wants to receive The volume of swap transactions has increased rapidly floating (variable) interest rate payments over a given in recent years (see Chart 1). Swaps are the largest period, and is prepared to pay the other party a fixed type of traded interest rate derivatives in the OTC rate to receive those floating payments. The floating (over-the-counter)(4) market, accounting for over 75% of rate is agreed in advance with reference to a specific short-term market rate (usually three-month or Chart 1 six-month Libor).(2) The fixed rate is called the swap rate OTC interest rate contracts by instrument in all and should reflect, among other things, the value each currencies Total interest rate swaps outstanding party attributes to the series of floating-rate payments to Total forward-rate agreements outstanding Total option contracts outstanding US$ trillions be made over the life of the contract. -

Ice Crude Oil

ICE CRUDE OIL Intercontinental Exchange® (ICE®) became a center for global petroleum risk management and trading with its acquisition of the International Petroleum Exchange® (IPE®) in June 2001, which is today known as ICE Futures Europe®. IPE was established in 1980 in response to the immense volatility that resulted from the oil price shocks of the 1970s. As IPE’s short-term physical markets evolved and the need to hedge emerged, the exchange offered its first contract, Gas Oil futures. In June 1988, the exchange successfully launched the Brent Crude futures contract. Today, ICE’s FSA-regulated energy futures exchange conducts nearly half the world’s trade in crude oil futures. Along with the benchmark Brent crude oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil and gasoil futures contracts, ICE Futures Europe also offers a full range of futures and options contracts on emissions, U.K. natural gas, U.K power and coal. THE BRENT CRUDE MARKET Brent has served as a leading global benchmark for Atlantic Oseberg-Ekofisk family of North Sea crude oils, each of which Basin crude oils in general, and low-sulfur (“sweet”) crude has a separate delivery point. Many of the crude oils traded oils in particular, since the commercialization of the U.K. and as a basis to Brent actually are traded as a basis to Dated Norwegian sectors of the North Sea in the 1970s. These crude Brent, a cargo loading within the next 10-21 days (23 days on oils include most grades produced from Nigeria and Angola, a Friday). In a circular turn, the active cash swap market for as well as U.S. -

Tax Treatment of Derivatives

United States Viva Hammer* Tax Treatment of Derivatives 1. Introduction instruments, as well as principles of general applicability. Often, the nature of the derivative instrument will dictate The US federal income taxation of derivative instruments whether it is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset is determined under numerous tax rules set forth in the US (see discussion of section 1256 contracts, below). In other tax code, the regulations thereunder (and supplemented instances, the nature of the taxpayer will dictate whether it by various forms of published and unpublished guidance is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset (see discus- from the US tax authorities and by the case law).1 These tax sion of dealers versus traders, below). rules dictate the US federal income taxation of derivative instruments without regard to applicable accounting rules. Generally, the starting point will be to determine whether the instrument is a “capital asset” or an “ordinary asset” The tax rules applicable to derivative instruments have in the hands of the taxpayer. Section 1221 defines “capital developed over time in piecemeal fashion. There are no assets” by exclusion – unless an asset falls within one of general principles governing the taxation of derivatives eight enumerated exceptions, it is viewed as a capital asset. in the United States. Every transaction must be examined Exceptions to capital asset treatment relevant to taxpayers in light of these piecemeal rules. Key considerations for transacting in derivative instruments include the excep- issuers and holders of derivative instruments under US tions for (1) hedging transactions3 and (2) “commodities tax principles will include the character of income, gain, derivative financial instruments” held by a “commodities loss and deduction related to the instrument (ordinary derivatives dealer”.4 vs. -

An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming John Jackson Ada Li Asani Sarkar Patricia Zobel Staff Report No. 557 March 2012 Revised October 2012 FRBNY Staff REPORTS This paper presents preliminary fi ndings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily refl ective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming, John Jackson, Ada Li, Asani Sarkar, and Patricia Zobel Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 557 March 2012; revised October 2012 JEL classifi cation: G12, G13, G18 Abstract This paper examines the over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives (IRD) market in order to inform the design of post-trade price reporting. Our analysis uses a novel transaction-level data set to examine trading activity, the composition of market participants, levels of product standardization, and market-making behavior. We fi nd that trading activity in the IRD market is dispersed across a broad array of product types, currency denominations, and maturities, leading to more than 10,500 observed unique product combinations. While a select group of standard instruments trade with relative frequency and may provide timely and pertinent price information for market partici- pants, many other IRD instruments trade infrequently and with diverse contract terms, limiting the impact on price formation from the reporting of those transactions. -

Panagora Global Diversified Risk Portfolio General Information Portfolio Allocation

March 31, 2021 PanAgora Global Diversified Risk Portfolio General Information Portfolio Allocation Inception Date April 15, 2014 Total Assets $254 Million (as of 3/31/2021) Adviser Brighthouse Investment Advisers, LLC SubAdviser PanAgora Asset Management, Inc. Portfolio Managers Bryan Belton, CFA, Director, Multi Asset Edward Qian, Ph.D., CFA, Chief Investment Officer and Head of Multi Asset Research Jonathon Beaulieu, CFA Investment Strategy The PanAgora Global Diversified Risk Portfolio investment philosophy is centered on the belief that risk diversification is the key to generating better risk-adjusted returns and avoiding risk concentration within a portfolio is the best way to achieve true diversification. They look to accomplish this by evaluating risk across and within asset classes using proprietary risk assessment and management techniques, including an approach to active risk management called Dynamic Risk Allocation. The portfolio targets a risk allocation of 40% equities, 40% fixed income and 20% inflation protection. Portfolio Statistics Portfolio Composition 1 Yr 3 Yr Inception 1.88 0.62 Sharpe Ratio 0.6 Positioning as of Positioning as of 0.83 0.75 Beta* 0.78 December 31, 2020 March 31, 2021 Correlation* 0.87 0.86 0.79 42.4% 10.04 10.6 Global Equity 43.4% Std. Deviation 9.15 24.9% U.S. Stocks 23.6% Weighted Portfolio Duration (Month End) 9.0% 8.03 Developed non-U.S. Stocks 9.8% 8.5% *Statistic is measured against the Dow Jones Moderate Index Emerging Markets Equity 10.0% 106.8% Portfolio Benchmark: Nominal Fixed Income 142.6% 42.0% The Dow Jones Moderate Index is a composite index with U.S. -

Interest Rate Swap Contracts the Company Has Two Interest Rate Swap Contracts That Hedge the Base Interest Rate Risk on Its Two Term Loans

$400.0 million. However, the $100.0 million expansion feature may or may not be available to the Company depending upon prevailing credit market conditions. To date the Company has not sought to borrow under the expansion feature. Borrowings under the Credit Agreement carry interest rates that are either prime-based or Libor-based. Interest rates under these borrowings include a base rate plus a margin between 0.00% and 0.75% on Prime-based borrowings and between 0.625% and 1.75% on Libor-based borrowings. Generally, the Company’s borrowings are Libor-based. The revolving loans may be borrowed, repaid and reborrowed until January 31, 2012, at which time all amounts borrowed must be repaid. The revolver borrowing capacity is reduced for both amounts outstanding under the revolver and for letters of credit. The original term loan will be repaid in 18 consecutive quarterly installments which commenced on September 30, 2007, with the final payment due on January 31, 2012, and may be prepaid at any time without penalty or premium at the option of the Company. The 2008 term loan is co-terminus with the original 2007 term loan under the Credit Agreement and will be repaid in 16 consecutive quarterly installments which commenced June 30, 2008, plus a final payment due on January 31, 2012, and may be prepaid at any time without penalty or premium at the option of Gartner. The Credit Agreement contains certain customary restrictive loan covenants, including, among others, financial covenants requiring a maximum leverage ratio, a minimum fixed charge coverage ratio, and a minimum annualized contract value ratio and covenants limiting Gartner’s ability to incur indebtedness, grant liens, make acquisitions, be acquired, dispose of assets, pay dividends, repurchase stock, make capital expenditures, and make investments. -

Derivative Valuation Methodologies for Real Estate Investments

Derivative valuation methodologies for real estate investments Revised September 2016 Proprietary and confidential Executive summary Chatham Financial is the largest independent interest rate and foreign exchange risk management consulting company, serving clients in the areas of interest rate risk, foreign currency exposure, accounting compliance, and debt valuations. As part of its service offering, Chatham provides daily valuations for tens of thousands of interest rate, foreign currency, and commodity derivatives. The interest rate derivatives valued include swaps, cross currency swaps, basis swaps, swaptions, cancellable swaps, caps, floors, collars, corridors, and interest rate options in over 50 market standard indices. The foreign exchange derivatives valued nightly include FX forwards, FX options, and FX collars in all of the major currency pairs and many emerging market currency pairs. The commodity derivatives valued include commodity swaps and commodity options. We currently support all major commodity types traded on the CME, CBOT, ICE, and the LME. Summary of process and controls – FX and IR instruments Each day at 4:00 p.m. Eastern time, our systems take a “snapshot” of the market to obtain close of business rates. Our systems pull over 9,500 rates including LIBOR fixings, Eurodollar futures, swap rates, exchange rates, treasuries, etc. This market data is obtained via direct feeds from Bloomberg and Reuters and from Inter-Dealer Brokers. After the data is pulled into the system, it goes through the rates control process. In this process, each rate is compared to its historical values. Any rate that has changed more than the mean and related standard deviation would indicate as normal is considered an outlier and is flagged for further investigation by the Analytics team. -

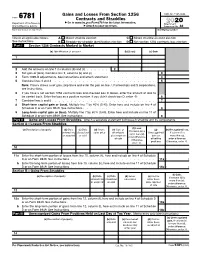

Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to for the Latest Information

Gains and Losses From Section 1256 OMB No. 1545-0644 Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form6781 for the latest information. 2020 Department of the Treasury Attachment Internal Revenue Service ▶ Attach to your tax return. Sequence No. 82 Name(s) shown on tax return Identifying number Check all applicable boxes. A Mixed straddle election C Mixed straddle account election See instructions. B Straddle-by-straddle identification election D Net section 1256 contracts loss election Part I Section 1256 Contracts Marked to Market (a) Identification of account (b) (Loss) (c) Gain 1 2 Add the amounts on line 1 in columns (b) and (c) . 2 ( ) 3 Net gain or (loss). Combine line 2, columns (b) and (c) . 3 4 Form 1099-B adjustments. See instructions and attach statement . 4 5 Combine lines 3 and 4 . 5 Note: If line 5 shows a net gain, skip line 6 and enter the gain on line 7. Partnerships and S corporations, see instructions. 6 If you have a net section 1256 contracts loss and checked box D above, enter the amount of loss to be carried back. Enter the loss as a positive number. If you didn’t check box D, enter -0- . 6 7 Combine lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Short-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 40% (0.40). Enter here and include on line 4 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. See instructions . 8 9 Long-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 60% (0.60). Enter here and include on line 11 of Schedule D or on Form 8949.