Systematically Bridging the Gap Between Novae and Supernovae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Dwarfs

Chandra X-Ray Observatory X-Ray Astronomy Field Guide White Dwarfs White dwarfs are among the dimmest stars in the universe. Even so, they have commanded the attention of astronomers ever since the first white dwarf was observed by optical telescopes in the middle of the 19th century. One reason for this interest is that white dwarfs represent an intriguing state of matter; another reason is that most stars, including our sun, will become white dwarfs when they reach their final, burnt-out collapsed state. A star experiences an energy crisis and its core collapses when the star's basic, non-renewable energy source - hydrogen - is used up. A shell of hydrogen on the edge of the collapsed core will be compressed and heated. The nuclear fusion of the hydrogen in the shell will produce a new surge of power that will cause the outer layers of the star to expand until it has a diameter a hundred times its present value. This is called the "red giant" phase of a star's existence. A hundred million years after the red giant phase all of the star's available energy resources will be used up. The exhausted red giant will puff off its outer layer leaving behind a hot core. This hot core is called a Wolf-Rayet type star after the astronomers who first identified these objects. This star has a surface temperature of about 50,000 degrees Celsius and is A composite furiously boiling off its outer layers in a "fast" wind traveling 6 million image of the kilometers per hour. -

Pos(INTEGRAL 2010)091

A candidate former companion star to the Magnetar CXOU J164710.2-455216 in the massive Galactic cluster Westerlund 1 PoS(INTEGRAL 2010)091 P.J. Kavanagh 1 School of Physical Sciences and NCPST, Dublin City University Glasnevin, Dublin 9, Ireland E-mail: [email protected] E.J.A. Meurs School of Cosmic Physics, DIAS, and School of Physical Sciences, DCU Glasnevin, Dublin 9, Ireland E-mail: [email protected] L. Norci School of Physical Sciences and NCPST, Dublin City University Glasnevin, Dublin 9, Ireland E-mail: [email protected] Besides carrying the distinction of being the most massive young star cluster in our Galaxy, Westerlund 1 contains the notable Magnetar CXOU J164710.2-455216. While this is the only collapsed stellar remnant known for this cluster, a further ~10² Supernovae may have occurred on the basis of the cluster Initial Mass Function, possibly all leaving Black Holes. We identify a candidate former companion to the Magnetar in view of its high proper motion directed away from the Magnetar region, viz. the Luminous Blue Variable W243. We discuss the properties of W243 and how they pertain to the former Magnetar companion hypothesis. Binary evolution arguments are employed to derive a progenitor mass for the Magnetar of 24-25 M Sun , just within the progenitor mass range for Neutron Star birth. We also draw attention to another candidate to be member of a former massive binary. 8th INTEGRAL Workshop “The Restless Gamma-ray Universe” Dublin, Ireland September 27-30, 2010 1 Speaker Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Licence. -

Luminous Blue Variables

Review Luminous Blue Variables Kerstin Weis 1* and Dominik J. Bomans 1,2,3 1 Astronomical Institute, Faculty for Physics and Astronomy, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2 Department Plasmas with Complex Interactions, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 3 Ruhr Astroparticle and Plasma Physics (RAPP) Center, 44801 Bochum, Germany Received: 29 October 2019; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 29 February 2020 Abstract: Luminous Blue Variables are massive evolved stars, here we introduce this outstanding class of objects. Described are the specific characteristics, the evolutionary state and what they are connected to other phases and types of massive stars. Our current knowledge of LBVs is limited by the fact that in comparison to other stellar classes and phases only a few “true” LBVs are known. This results from the lack of a unique, fast and always reliable identification scheme for LBVs. It literally takes time to get a true classification of a LBV. In addition the short duration of the LBV phase makes it even harder to catch and identify a star as LBV. We summarize here what is known so far, give an overview of the LBV population and the list of LBV host galaxies. LBV are clearly an important and still not fully understood phase in the live of (very) massive stars, especially due to the large and time variable mass loss during the LBV phase. We like to emphasize again the problem how to clearly identify LBV and that there are more than just one type of LBVs: The giant eruption LBVs or h Car analogs and the S Dor cycle LBVs. -

Systematically Bridging the Gap Between Novae and Supernovae

CSIRO PUBLISHING Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, 2012, 29, 482–488 Review http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/AS11061 Systematically Bridging the Gap Between Novae and Supernovae M. M. Kasliwal Department of Astronomy, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd, M/C 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA, and Carnegie Institution for Science, 813 Santa Barbara St, Pasadena, CA 91101, USA Email: [email protected] Abstract: The venerable study of cosmic explosions is over a century old. However, until recently, there has existed a glaring six-magnitude luminosity gap between the brightest novae and faintest supernovae. Serendipitous discoveries, archival searches and ongoing systematic surveys are yielding optical transients that are fainter, faster and rarer than supernovae. Theorists predict a variety of mechanisms to produce transients in the gap and observers have the best chance of finding them in the local Universe. Here I review the discoveries and the unique physics of cosmic explosions that bridge this gap between novae and supernovae. Keywords: surveys — novae, cataclysmic variables — supernovae: general Received 2011 October 18, accepted 2012 June 15, published online 2012 July 12 1 Introduction and supernovae. Ultraviolet/X-ray transients, variable The venerable field of cosmic explosions has a rich stars (e.g. luminous blue variables), and extremely history. Since the discovery of the first supernova in AD luminous supernovae are not discussed here. 185 and the first nova in AD 1670, we have discovered E 6600 supernovae and E 1000 novae. In the past cen- 2 Theoretically Predicted Transients in the Gap tury, explosions have unveiled the synthesis of elements Theoretically, a wide variety of fundamental stellar heavier than iron, the acceleration of the Universe’s outcomes are expected to result in transients in the gap. -

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants There is a large variety of stellar models which have a distinct core – envelope structure. While any main sequence star, or any white dwarf, may be well approximated with a single polytropic model, the stars with the core – envelope structure may be approximated with a composite polytrope: one for the core, another for the envelope, with a very large difference in the “K” constants between the two. This is a consequence of a very large difference in the specific entropies between the core and the envelope. The original reason for the difference is due to a jump in chemical composition. For example, the core may have no hydrogen, and mostly helium, while the envelope may be hydrogen rich. As a result, there is a nuclear burning shell at the bottom of the envelope; hydrogen burning shell in our example. The heat generated in the shell is diffusing out with radiation, and keeps the entropy very high throughout the envelope. The core – envelope structure is most pronounced when the core is degenerate, and its specific entropy near zero. It is supported against its own gravity with the non-thermal pressure of degenerate electron gas, while all stellar luminosity, and all entropy for the envelope, are provided by the shell source. A common property of stars with well developed core – envelope structure is not only a very large jump in specific entropy but also a very large difference in pressure between the center, Pc, the shell, Psh, and the photosphere, Pph. Of course, the two characteristics are closely related to each other. -

Supernovae Sparked by Dark Matter in White Dwarfs

Supernovae Sparked By Dark Matter in White Dwarfs Javier F. Acevedog and Joseph Bramanteg;y gThe Arthur B. McDonald Canadian Astroparticle Physics Research Institute, Department of Physics, Engineering Physics, and Astronomy, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, K7L 2S8, Canada yPerimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, Ontario, N2L 2Y5, Canada November 27, 2019 Abstract It was recently demonstrated that asymmetric dark matter can ignite supernovae by collecting and collapsing inside lone sub-Chandrasekhar mass white dwarfs, and that this may be the cause of Type Ia supernovae. A ball of asymmetric dark matter accumulated inside a white dwarf and collapsing under its own weight, sheds enough gravitational potential energy through scattering with nuclei, to spark the fusion reactions that precede a Type Ia supernova explosion. In this article we elaborate on this mechanism and use it to place new bounds on interactions between nucleons 6 16 and asymmetric dark matter for masses mX = 10 − 10 GeV. Interestingly, we find that for dark matter more massive than 1011 GeV, Type Ia supernova ignition can proceed through the Hawking evaporation of a small black hole formed by the collapsed dark matter. We also identify how a cold white dwarf's Coulomb crystal structure substantially suppresses dark matter-nuclear scattering at low momentum transfers, which is crucial for calculating the time it takes dark matter to form a black hole. Higgs and vector portal dark matter models that ignite Type Ia supernovae are explored. arXiv:1904.11993v3 [hep-ph] 26 Nov 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Dark matter capture, thermalization and collapse in white dwarfs 4 2.1 Dark matter capture . -

The Impact of the Astro2010 Recommendations on Variable Star Science

The Impact of the Astro2010 Recommendations on Variable Star Science Corresponding Authors Lucianne M. Walkowicz Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley [email protected] phone: (510) 642–6931 Andrew C. Becker Department of Astronomy, University of Washington [email protected] phone: (206) 685–0542 Authors Scott F. Anderson, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Joshua S. Bloom, Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley Leonid Georgiev, Universidad Autonoma de Mexico Josh Grindlay, Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Steve Howell, National Optical Astronomy Observatory Knox Long, Space Telescope Science Institute Anjum Mukadam, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Andrej Prsa,ˇ Villanova University Joshua Pepper, Villanova University Arne Rau, California Institute of Technology Branimir Sesar, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Nicole Silvestri, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Nathan Smith, Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley Keivan Stassun, Vanderbilt University Paula Szkody, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Science Frontier Panels: Stars and Stellar Evolution (SSE) February 16, 2009 Abstract The next decade of survey astronomy has the potential to transform our knowledge of variable stars. Stellar variability underpins our knowledge of the cosmological distance ladder, and provides direct tests of stellar formation and evolution theory. Variable stars can also be used to probe the fundamental physics of gravity and degenerate material in ways that are otherwise impossible in the laboratory. The computational and engineering advances of the past decade have made large–scale, time–domain surveys an immediate reality. Some surveys proposed for the next decade promise to gather more data than in the prior cumulative history of astronomy. -

POSTERS SESSION I: Atmospheres of Massive Stars

Abstracts of Posters 25 POSTERS (Grouped by sessions in alphabetical order by first author) SESSION I: Atmospheres of Massive Stars I-1. Pulsational Seeding of Structure in a Line-Driven Stellar Wind Nurdan Anilmis & Stan Owocki, University of Delaware Massive stars often exhibit signatures of radial or non-radial pulsation, and in principal these can play a key role in seeding structure in their radiatively driven stellar wind. We have been carrying out time-dependent hydrodynamical simulations of such winds with time-variable surface brightness and lower boundary condi- tions that are intended to mimic the forms expected from stellar pulsation. We present sample results for a strong radial pulsation, using also an SEI (Sobolev with Exact Integration) line-transfer code to derive characteristic line-profile signatures of the resulting wind structure. Future work will compare these with observed signatures in a variety of specific stars known to be radial and non-radial pulsators. I-2. Wind and Photospheric Variability in Late-B Supergiants Matt Austin, University College London (UCL); Nevyana Markova, National Astronomical Observatory, Bulgaria; Raman Prinja, UCL There is currently a growing realisation that the time-variable properties of massive stars can have a funda- mental influence in the determination of key parameters. Specifically, the fact that the winds may be highly clumped and structured can lead to significant downward revision in the mass-loss rates of OB stars. While wind clumping is generally well studied in O-type stars, it is by contrast poorly understood in B stars. In this study we present the analysis of optical data of the B8 Iae star HD 199478. -

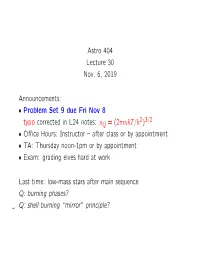

Astro 404 Lecture 30 Nov. 6, 2019 Announcements

Astro 404 Lecture 30 Nov. 6, 2019 Announcements: • Problem Set 9 due Fri Nov 8 2 3/2 typo corrected in L24 notes: nQ = (2πmkT/h ) • Office Hours: Instructor – after class or by appointment • TA: Thursday noon-1pm or by appointment • Exam: grading elves hard at work Last time: low-mass stars after main sequence Q: burning phases? 1 Q: shell burning “mirror” principle? Low-Mass Stars After Main Sequence unburnt H ⋆ helium core contracts H He H burning in shell around core He outer layers expand → red giant “mirror” effect of shell burning: • core contraction, envelope expansion • total gravitational potential energy Ω roughly conserved core becomes more tightly bound, envelope less bound ⋆ helium ignition degenerate core unburnt H H He runaway burning: helium flash inert He → 12 He C+O 2 then core helium burning 3α C and shell H burning “horizontal branch” star unburnt H H He ⋆ for solar mass stars: after CO core forms inert He He C • helium shell burning begins inert C • hydrogen shell burning continues Q: star path on HR diagram during these phases? 3 Low-Mass Post-Main-Sequence: HR Diagram ⋆ H shell burning ↔ red giant ⋆ He flash marks “tip of the red giant branch” ⋆ core He fusion ↔ horizontal branch ⋆ He + H shell burning ↔ asymptotic giant branch asymptotic giant branch H+He shell burn He flash core He burn L main sequence horizontal branch red giant branch H shell burning Sun Luminosity 4 Temperature T iClicker Poll: AGB Star Intershell Region in AGB phase: burning in two shells, no core fusion unburnt H H He inert He He C Vote your conscience–all -

Fundamental Parameters of 4 Massive Eclipsing Binaries in Westerlund 1

Active OB stars: structure, evolution, mass loss and critical limits Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 272, 2010 c 2010 International Astronomical Union C. Neiner, G. Wade, G. Meynet & G. Peters DOI: 00.0000/X000000000000000X Fundamental Parameters of 4 Massive Eclipsing Binaries in Westerlund 1 E. Koumpia and A.Z. Bonanos † National Observatory of Athens, Institute of Astronomy & Astrophysics, I. Metaxa & Vas. Pavlou St., Palaia Penteli GR-15236 Athens, Greece [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Westerlund 1 is one of the most massive young clusters known in the Local Group, with an age of 3-5 Myr. It contains an assortment of rare evolved massive stars, such as blue, yellow and red supergiants, Wolf-Rayet stars, a luminous blue variable, and a magnetar, as well as 4 massive eclipsing binary systems (Wddeb, Wd13, Wd36, WR77o, see Bonanos 2007). The eclipsing binaries present a rare opportunity to constrain evolutionary models of massive stars, the distance to the cluster and furthermore, to determine a dynamical lower limit for the mass of a magnetar progenitor. Wddeb, being a detached system, is of great interest as it allows determination of the masses of 2 of the most massive unevolved stars in the cluster. We have analyzed spectra of all 4 eclipsing binaries, taken in 2007-2008 with the 6.5 meter Magellan telescope at Las Campanas Observatory, Chile, and present fundamental parameters (masses, radii) for their component stars. Keywords. open clusters and associations: individual (Westerlund 1), stars: fundamental pa- rameters, stars: early-type, binaries: eclipsing, stars: Wolf-Rayet 1. Introduction Westerlund 1 (Wd1) is one of the most massive compact young star clusters known in the Local Group. -

Neutron Stars: End State of High-Mass Stars

Chapter 13: The Stellar Graveyard 3/31/2009 Habbal Astro110http://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2001/1227/index.html Chapter 13 Lecture 26 1 Low mass star High mass (>8 Msun) star Ends as a white dwarf. Ends in a supernova, leaving a neutron star or black hole 3/31/2009 Habbal Astro110 Chapter 13 Lecture 26 2 White dwarfs: end state of low-mass stars • Inert remaining cores of dead low-mass stars. • No internal energy generation: start hot and steadily cool off. Optical image X-ray image Sirius A Sirius A high mass star high mass star Sirius B Sirius B white dwarf white dwarf 3/31/2009 Habbal Astro110 Chapter 13 Lecture 26 3 White dwarfs are supported against gravitational collapse by electron degeneracy pressure 3/31/2009 Habbal Astro110 Chapter 13 Lecture 26 4 A 1 MSun white dwarf is about the same size as the Earth… ⇒ A teaspoon of white dwarf material would weight 10 tons! 3/31/2009 Habbal Astro110 Chapter 13 Lecture 26 5 More massive white dwarfs are smaller! Mass ⇒ gravitational compression ⇒ density ⇒ radius Chandrasekhar limit: white dwarfs cannot be more massive than 1.4 MSun 3/31/2009 Habbal Astro110 Chapter 13 Lecture 26 6 White dwarfs in binary systems • WDʼs gravity can accrete gas from companion star. • Accreted gas can erupt in a short modest burst of nuclear fusion: novae • However, WDs cannot BANG! be more than 1.4 MSun. • If WD accretes too much gas, it is destroyed in a white dwarf supernova 3/31/2009 Habbal Astro110 Chapter 13 Lecture 26 7 Nova: a nuclear explosion on the surface of a WD, gas is expelled and system returns to normal 3/31/2009 Habbal Astro110 Chapter 13 Lecture 26 8 One way to tell supernova types apart is with a light curve showing how the luminosity changes. -

Stellar Death: White Dwarfs, Neutron Stars, and Black Holes

Stellar death: White dwarfs, Neutron stars & Black Holes Content Expectaions What happens when fusion stops? Stars are in balance (hydrostatic equilibrium) by radiation pushing outwards and gravity pulling in What will happen once fusion stops? The core of the star collapses spectacularly, leaving behind a dead star (compact object) What is left depends on the mass of the original star: <8 M⦿: white dwarf 8 M⦿ < M < 20 M⦿: neutron star > 20 M⦿: black hole Forming a white dwarf Powerful wind pushes ejects outer layers of star forming a planetary nebula, and exposing the small, dense core (white dwarf) The core is about the radius of Earth Very hot when formed, but no source of energy – will slowly fade away Prevented from collapsing by degenerate electron gas (stiff as a solid) Planetary nebulae (nothing to do with planets!) THE RING NEBULA Planetary nebulae (nothing to do with planets!) THE CAT’S EYE NEBULA Death of massive stars When the core of a massive star collapses, it can overcome electron degeneracy Huge amount of energy BAADE ZWICKY released - big supernova explosion Neutron star: collapse halted by neutron degeneracy (1934: Baade & Zwicky) Black Hole: star so massive, collapse cannot be halted SN1006 1967: Pulsars discovered! Jocelyn Bell and her supervisor Antony Hewish studying radio signals from quasars Discovered recurrent signal every 1.337 seconds! Nicknamed LGM-1 now called PSR B1919+21 BRIGHTNESS TIME NATURE, FEBRUARY 1968 1967: Pulsars discovered! Beams of radiation from spinning neutron star Like a lighthouse Neutron