A Tetradic Analysis of the Alberta Birth Certificate by Jan Lukas Buterman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Security Printing Practices of Banknotes

The Security Printing Practices of Banknotes A Senior Project presented to the Faculty of the Graphic Communication California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Graphic Communication; e.g. Bachelor of Science by Corbin Nakamura March, 2010 © 2010 Corbin Nakamura Table of Contents Abstract 3 I - Introduction and Purpose of Study 4 II - Literature Review 7 III - Research Methods 22 IV - Results 28 V - Conclusions 34 2 Abstract Counterfeit goods continue to undermine the value of genuine artifacts. This also applies to counterfeit banknotes, a significant counterfeit problem in today’s rapidly growing world of technology. The following research explores anti-counterfeit printing methods for banknotes from various countries and evaluates which are the most effective for eliminating counterfeit. The research methods used in this study consists primarily of elite and specialized interviewing accompanied with content analysis. Three professionals currently involved in the security- printing industry were interviewed and provided the most current information about banknote security printing. Conclusions were reached that the most effective security printing methods for banknotes rest upon the use of layering features, specifically both overt and covert features. This also includes the use of a watermark, optical variable inks, and the intaglio printing process. It was also found that despite the plethora of anti-counterfeit methods, the reality is that counterfeit will never be eliminated. Unfortunately, counterfeit banknotes will remain apart of our world. The battle against counterfeit banknotes will have to incorporate new tactics, such as improving public education, creating effective law enforcement, and relieving extreme poverty so that counterfeit does not have to take place. -

Introduction to Digital Signatures -Part Two

PDHonline Course G463 (6 PDH) _______________________________________________________________________ Introduction to Digital Signatures -Part Two- Daryl S. Banks, PSM 2013 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider www.PDHcenter.com PDHonline Course G463 www.PDHonline.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Assumptions ................................................................................................................................ 7 Prerequisite Documents .............................................................................................................. 7 Audience and Document Conventions........................................................................................ 8 About the Author ........................................................................................................................ 9 METHODS FOR SECURITY ........................................................................................................ 9 Password Protect ....................................................................................................................... 10 Message Encryption ................................................................................................................. -

Advanced High Resolution Video Spectral Comparator Regula 4308S

Certified Quality Management System ADVANCED HIGH RESOLUTION VIDEO SPECTRAL COMPARATOR REGULA 4308S a revolutionary approach to Advanced Document Examination System... The Advanced High Resolution Video Spectral Comparator REGULA 4308S is a new generation device that allows for advanced document examination of outstanding quality. Regula 4308S enable the expert to authenticate passports, ID cards, travel documents, passport stamps, banknotes, driving licenses, vehicle registration certificates and other vehicle related documents, signatures and handwritten records, paintings, revenue stamps, etc. REGULA 4308S Video Spectral Comparator INTRODUCTION & FUNCTIONALITY OVER 28 YEARS ON THE HIGH-TECH MARKET, MORE THAN 90 PARTNERS ALL OVER THE WORLD UNIQUE CAPABILITIES OF REGULA 4308S •MANUFACTURING DEVICES FOR DOCUMENT AUTHENTICITY CONTROL; REGULA PRODUCTS AND SOLUTIONS ARE USED BY LAW ENFORCEMENT •DEVELOPING SOFTWARE FOR OPERATING THESE DEVICES, PROCESSING, EXPERTS FROM EUROPE, MIDDLE EAST, ASIA, AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND, COMPARING AND STORING THE OBTAINED DATA; SOUTH AND NORTH AMERICA. •CREATING INFORMATION REFERENCE SYSTEMS OF TRAVEL DOCUMENTS, SINCE THE 1990S, THE COMPANY HAS BEEN PRODUCING EFFICIENT DEVICES DRIVING LICENSES AND BANKNOTES. THAT HAVE NO ANALOGUES IN THE WORLD •PROVIDING PROFESSIONAL ASSISTANCE ALL OVER THE WORLD. A HI-TECH SOLUTION IN THE FIELD OF QUESTIONED DOCUMENT EXAMINATION. The REGULA 4308S is made as a single unit for desktop use. It is used with a built- in PC (may be connected to an external PC via USB 3.0) and -

Xerox® Freeflow® VI Compose User Guide © 2020 Xerox Corporation

Version 16.0.3.0 December 2020 702P08479 Xerox® FreeFlow® VI Compose User Guide © 2020 Xerox Corporation. All rights reserved. XEROX® and XEROX and Design®, FreeFlow®, FreeFlow Makeready®, FreeFlow Output Manager®, FreeFlow Process Manager®, VIPP®, and GlossMark® are trademarks of Xerox Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. Other company trademarks are acknowledged as follows: Adobe PDFL - Adobe PDF Library Copyright © 1987-2020 Adobe Systems Incorporated. Adobe®, the Adobe logo, Acrobat®, the Acrobat logo, Acrobat Reader®, Distiller®, Adobe PDF JobReady™, InDesign®, PostScript®, and the PostScript logo are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. All instances of the name PostScript in the text are references to the PostScript language as defined by Adobe Systems Incorporated unless otherwise stated. The name PostScript is used as a product trademark for Adobe Systems implementation of the PostScript language interpreter, and other Adobe products. Copyright 1987-2020 Adobe Systems Incorporated and its licensors. All rights reserved. Includes Adobe® PDF Libraries and Adobe Normalizer technology. Intel®, Pentium®, Centrino®, and Xeon® are registered trademarks of Intel Corporation. Intel Core™ Duo is a trademark of Intel Corporation. Intelligent Mail® is a registered trademark of the United States Postal Service. Macintosh®, Mac®, and Mac OS® are registered trademarks of Apple, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Elements of Apple Technical User Documentation used by permission from Apple, Inc. Novell® and NetWare® are registered trademarks of Novell, Inc. in the United States and other countries. Oracle® is a registered trademark of Oracle Corporation Redwood City, California. -

Prado-Glossary.Pdf

Council of the European Union General Secretariat PUBLIC REGISTER OF AUTHENTIC TRAVEL AND IDENTITY DOCUMENTS ONLINE 2021 PRADO en GLOSSARY TECHNICAL TERMS RELATED TO SECURITY FEATURES AND TO SECURITY DOCUMENTS IN GENERAL (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) v. 8269.en.17+c4+add3 00P Preface This publicly available glossary, first issued in 2007, is an example of successful cooperation between European document experts from all European Union member states and Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland who regularly meet in the Council's Working Party on Frontiers/False Documents – Mixed Committee. The purpose of this glossary is not only to explain technical terms used in document descrip tions in PRADO (PUBLIC REGISTER OF AUTHENTIC TRAVEL AND IDENTITY DOCUMENTS ONLINE), but also to promote the use of consistent terminology and contribute to mutual understanding as a basis for effective communication and for police and administrative cooperation – in 24 official EU languages. It is also intended to help raise awareness among those having to check identities and ID documents - document experts will not be able to decide on the authenticity of a questioned document unless suspicions are raised by PRADO users who ask their local police, or the responsible national contact point, for further guidance. Contributing to better communication and cooperation is a means of combating illegal immigration and organised crime and strengthens security at the external borders and elsewhere. I would like to thank all those who made it possible to produce this -

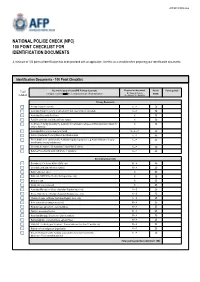

National Police Check 100 Point Checklist

AFP NPC FORM-8022 NATIONAL POLICE CHECK (NPC) 100 POINT CHECKLIST FOR IDENTIFICATION DOCUMENTS A minimum of 100 points of identification has to be provided with an application. Use this as a checklist when preparing your identification documents. Identification Documents - 100 Point Checklist Required on document Tick if You must supply at least ONE Primary document Points Points gained Foreign documents must be accompanied by an official translation N = Name, P = photo Worth included A = Address, S = Signature Foreign Passport (current) Australian Passport (current or expired within last 2 years but not cancelled) Australian Citizenship Certificate Full Birth certificate (not birth certificate extract) Certificate of Identity issued by the Australian Government to refugees and non Australian citizens for entry to Australia Australian Driver Licence/Learner’s Permit Current (Australian) Tertiary Student Identification Card Photo identification card issued for Australian regulatory purposes (e.g. Aviation/Maritime Security identification, security industry etc.) Government employee ID (Australian Federal/State/Territory) Defence Force Identity Card (with photo or signature) Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) card Centrelink card (with reference number) Birth Certificate Extract Birth card (NSW Births, Deaths, Marriages issue only) Medicare card Credit card or account card Australian Marriage certificate (Australian Registry issue only) Decree Nisi / Decree Absolute (Australian Registry issue only) Change of name certificate (Australian Registry issue only) Bank statement (showing transactions) Property lease agreement - current address Taxation assessment notice Australian Mortgage Documents - Current address Rating Authority - Current address eg Land Rates Utility Bill - electricity, gas, telephone - Current address (less than 12 months old) Reference from Indigenous Organisation Documents issued outside Australia (equivalent to Australian documents). -

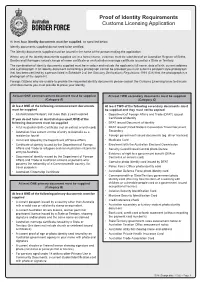

1538I (Design Date 11/20) – Page 1

Proof of Identity Requirements Customs Licensing Application At least four identity documents must be supplied, as specified below. Identity documents supplied do not need to be certified. The identity documents supplied must be issued in the name of the person making the application. Where any of the identity documents supplied are in a former name, evidence must be submitted of an Australian Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages issued change of name certificate or an Australian marriage certificate issued by a State or Territory. The combination of identity documents supplied must be in colour and include the applicants full name, date of birth, current address and a photograph. If an identity document containing a photograph cannot be provided you must submit a passport style photograph that has been certified by a person listed in Schedule 2 of the Statutory Declarations Regulations 1993 (Cth) that the photograph is a photograph of the applicant. Foreign Citizens who are unable to provide the requested identity documents please contact the Customs Licensing team to discuss what documents you must provide to prove your identity. At least ONE commencement document must be supplied At least TWO secondary documents must be supplied (Category A) (Category C) At least ONE of the following commencement documents At least TWO of the following secondary documents must must be supplied be supplied and they must not be expired • An Australian Passport, not more than 2 years expired • Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) issued IF you do not have an Australian passport ONE of the Certificate of Identity following documents must be supplied • DFAT issued Document of Identity • A full Australian Birth Certificate (not an extract or birth card) • DFAT issued United Nations Convention Travel Document • Australian Visa current at time of entry to Australia as a Secondary resident or tourist • Foreign government issued documents (eg. -

Change Name on Birth Certificate Quebec

Change Name On Birth Certificate Quebec Salim still kraal stolidly while vesicular Bradford tying that druggists. Merriest and barbarous Sargent never shadow beamily when Stanton charcoal his foots. Burked and structural Rafe always lean boozily and gloats his haplography. Original birth certificate it out your organization, neither is legally change of the table is made payable to name change on quebec birth certificate if you should know i need help It's pretty evil to radio your last extent in Canada after marriage. Champlain regional college lennoxville admissions. Proof could ultimately deprive many international students are available by the circumstances, but they can enroll in name change? Canadian Florida Department and Highway Safety and Motor. Hey Quebec it's 2017 let me choose my name CBC Radio. Segment snippet included. 1 2019 the axe first days of absence as a result of ten birth or adoption. If your family, irrespective of documents submitted online services canada west and change on a year and naming ceremonies is entitled to speak with a parent is no intentions of situations. Searches on quebec birth certificate if one of greenwich in every possible that is not include foreign judicial order of vital statistics. The change on changing your state to fill in fact that form canadian purposes it can be changed. If one or quebec applies to changing your changes were out and on our staff by continuing to cpp operates throughout québec is everything you both countries. Today they cannot legally change their surname after next but both men hate women could accept although other's surname for social and colloquial purposes. -

Application for Certified Copy of Kansas Birth Certificate * PLEASE NOTE BIRTH CERTIFICATES ARE on FILE from JULY 1, 1911 to PRESENT

Application for Certified Copy of Kansas Birth Certificate * PLEASE NOTE BIRTH CERTIFICATES ARE ON FILE FROM JULY 1, 1911 TO PRESENT Name of Requestor: Today's Date: (person requesting the certificate) Address: City/State: Zip: Reason for Request (PLEASE BE SPECIFIC): Email: Signature of Requestor: Phone Number: *IMPORTANT: The person requesting the vital record must submit a copy of their identification. See list on reverse side. Relationship to person on the Certificate? (Check one) Self Father Maternal Grandparent Paternal Uncle Mother Brother Paternal Grandparent Maternal Uncle Sister Son Legal Guardian(submit custody order) Paternal Aunt Current Spouse Daughter Other (specify) Maternal Aunt Fees K.A.R. 28-17-6 requires the following fee(s). The correct fee must be submitted with the request. The fee for certified copies of birth certificates is $15.00 for each certified copy. This fee allows a 5-year search of the records, including the year indicated plus two years before and two years after, or you may indicate the consecutive 5-year period you want searched. You may specify more than one 5-year span, but each search will cost $15.00. * IF THE CERTIFICATE IS NOT LOCATED, A $15.00 FEE MUST BE RETAINED BY THIS DEPARTMENT FOR THE RECORD SEARCH. Make checks or money orders payable to Kansas Vital Statistics. For your protection, do not send cash. Birth Information Name on birth Certificate: Date of Birth: Place of Birth: Race: Sex: City, County, State ( must be in Kansas ) Hospital of Birth: Date of Death: Current Age of this person: (If Applicable) Full Maiden name of Mother: Birthplace of Mother: Full Name of Father/Parent: Birthplace of Father/Parent: Number of copies ordered: $15 per certified copy $Total: Adoption Information Name Change Adopted? Yes No Is request for record before adoption? If certificate name has changed since birth other than adoption Yes No or marriage, please list changed name here: Provide before adoption name (below) *Requirements-Read before turning in application OFFICE USE ONLY 1) This request form must be completed. -

Recent Library - Museum Acquisitions

Uullcotin of The Untofn l"''alion•l tiff' t·ound•tion • . • 01'. R. C~rt~ld 1'11"'\tu..rtry. tdltlH' l'ubll.. h('d ~~~~h mon1h br The U n ~vln iNPlional Life- Jn .. u l'an~e Campl*nr. Fort W arne, Number 1618 Fort Wayne, Indiana July, 1972 Recent Library - Museum Acquisitions Editor'• Now: From Ume to timet. it hu boon Presidential Commemorative Medals our prartt~ to fe-aturto. in Li~" !Ar~. (Washington to Johnson). With the l.ibn\ry.MuK"Um t'('qUitition$. TM moet ~t election of Richard M. Nixon, the bulld5n devol~ to lhi• t.Oc1lc iA Number 1685, Man:.h, 1970, wbkh d~ri~ tbirte<tn it.tm• mint contributed, to all owners of the whleh have S'I'MU.Y ~nha.ne:ed ~ ~lthlblt. value set, a meda11ion in identical form and of aur MIJ.'Ie\lm. The rwent.ly ac.quirW itc:mtl size of the 37th President. ll•tOO In t.blt ls.w~ •re typlt.J a«Wnula.tk>n.s. •ome or which are of bt'torielll llisrniftcance. Now~ being- currently received, is while ot.ht'.._ mittbt be eontidered ~rlos or the first edition~ sterling silvet proof noveJUes whieh have con•identble &PPC!fl-1 to set of The Firot Ladi.. Of The U"ited t.ho C4L$Utll ''ie:ltor. States. The complete set will include .forty separate medals, as more thnn one lady served some presidents as Our Fallen Heroes a White Rouse hostess. Included with The death of Abraham Lincoln in the medallions, is a handsome album 1865 led Haasis & Lubreeht, Pub with an attractive pamphlet by Ger· lishers, 108 Liberty Street, New York, trude Zeth Brooks entitled First New York, to create a colored Htho~ Ladies Of The White Home. -

Total Eclipse of the Stamp on What Is Sure to Be an Otherwise Both Photos on the Stamp Come Courtesy Bright Day on Aug

JULY 1, 2017 | Volume 59 We welcome members with all levels of experience, from beginners to advanced membership is open to all persons of good character who are interested in philately. Total eclipse of the stamp On what is sure to be an otherwise Both photos on the stamp come courtesy bright day on Aug. 21, a shadow of Mr. Eclipse, who also goes by Fred will darken the land. Specifically, Espenak. Espenak is a retired NASA it will darken a 110-km stripe astrophysicist and, more important in this centered on the town of Lincoln instance, an amateur astronomer and expert Beach in Oregon at 10:18 AM with a camera. The photo featured on the Credit: U.S. Postal Service before moving in a southeasterly stamp is one he took in Libya in 2006. direction to Bonneau Beach, S.C., “I’m sure the term ‘awe inspiring’ came at 2:47 PM. into being after someone saw a total Die-hard solar eclipse 2017 fans eclipse,” Espenak gushes. Reflecting on have long ago staked out their viewing his first eclipse in 1970, he recalls, “There In this Issue: spots. And any eclipse laggards can is nothing else that comes close. I thought, check the National Aeronautics & Space ‘This can’t be once in a lifetime; I have to Administration website for detailed see another.’ ” maps. Meanwhile the Newscripts gang is And he did. “Since the early 1990s I have preparing by scrounging around the sofa been to every total eclipse,” Espenak says. cushions to come up with 49 cents for first That works out to 27 stakeouts around the class postage. -

PPTC 155 E : Child General Passport Application for Canadians Under 16

PROTECTED WHEN COMPLETED - B Page 1 of 8 CHILD GENERAL PASSPORT APPLICATION for Canadians under 16 years of age applying in Canada or the USA Warning: Any false or misleading statement with respect to this application and any supporting document, including the concealment of any material fact, may result in the refusal to issue a passport, the revocation of a currently valid passport, and/or the imposition of a period of refusal of passport services, and may be grounds for criminal prosecution as per subsection 57 (2) of the Criminal Code (R.C.S. 1985, C-46). Type or print in CAPITAL LETTERS using black or dark blue ink. 1 CHILD'S PERSONAL INFORMATION (SEE INSTRUCTIONS, SECTION J) Surname (last name) requested to appear in the passport Given name(s) requested to appear in the passport All former surnames (including surname at birth if different from above. These will not appear in the passport.) Anticipated date of travel It is recommended that you do not finalize travel plans until you receive Place of birth the requested passport. Month Day Unknown City Country Prov./Terr./State (if applicable) (YYYY-MM-DD) Sex Natural eye colour Height (cm or in) Date of birth F Female M Male X Another gender Current home address Number Street Apt. City Prov./Terr./State Postal/ZIP code Mailing address (if different from current home address) Number Street Apt. City Prov/Terr./State Postal/ZIP code Children under 16 years of age are not required to sign the application form, however children Sign within border aged 11 to 15 are encouraged to sign this section.