Chesapeake Bay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conowingo Tunnel and the Anthracite Mine Flood-Control Project a Historical Perspective on a “Solution” to the Anthracite Mine Drainage Problem

The Conowingo Tunnel and the Anthracite Mine Flood-Control Project A Historical Perspective on a “Solution” to the Anthracite Mine Drainage Problem Michael C. Korb, P.E. Environmental Program Manager Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation (BAMR) Wilkes Barre District Office [email protected] www.depweb.state.pa.us Abstract Fifty-seven years ago, Pennsylvania’s Anthracite Mine Drainage Commission recommended that the Conowingo Tunnel, an expensive, long-range solution to the Anthracite Mine Drainage problem, be “tabled” and that a cheaper, short-range “job- stimulus” project be implemented instead. Today Pennsylvania’s anthracite region has more than 40 major mine water discharges, which have a combined average flow of more than 285,000 gallons per minute (GPM). Two of these average more than 30,000 GPM, 10 more of the discharges are greater than 6,000 GPM, while another 15 average more than 1,000 GPM. Had the Conowingo Tunnel Project been completed, most of this Pennsylvania Anthracite mine water problem would have been Maryland’s mine water problem. Between 1944 and 1954, engineers of the US Bureau of Mines carried out a comprehensive study resulting in more than 25 publications on all aspects of the mine water problem. The engineering study resulted in a recommendation of a fantastic and impressive plan to allow the gravity drainage of most of the Pennsylvania anthracite mines into the estuary of the Susquehanna River, below Conowingo, Maryland, by driving a 137-mile main tunnel with several laterals into the four separate anthracite fields. The $280 million (1954 dollars) scheme was not executed, but rather a $17 million program of pump installations, ditch installation, stream bed improvement and targeted strip-pit backfilling was initiated. -

Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Section 106 Annual Report - 2019

Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Section 106 Annual Report - 2019 Prepared by: Cultural Resources Unit, Environmental Policy and Development Section, Bureau of Project Delivery, Highway Delivery Division, Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Date: April 07, 2020 For the: Federal Highway Administration, Pennsylvania Division Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Officer Advisory Council on Historic Preservation Penn Street Bridge after rehabilitation, Reading, Pennsylvania Table of Contents A. Staffing Changes ................................................................................................... 7 B. Consultant Support ................................................................................................ 7 Appendix A: Exempted Projects List Appendix B: 106 Project Findings List Section 106 PA Annual Report for 2018 i Introduction The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) has been delegated certain responsibilities for ensuring compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (Section 106) on federally funded highway projects. This delegation authority comes from a signed Programmatic Agreement [signed in 2010 and amended in 2017] between the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), and PennDOT. Stipulation X.D of the amended Programmatic Agreement (PA) requires PennDOT to prepare an annual report on activities carried out under the PA and provide it to -

3702 Curtin Road November 15, 2011

APPLICATION TO THE USDA-ARS LONG TERM AGRO-ECOSYSTEM RESEARCH (LTAR) NETWORK FOR THE PASTURE SYSTEMS AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT RESEARCH UNIT’S UPPER CHESAPEAKE BAY / SUSQUEHANNA RIVER COMPONENT PASTURE SYSTEMS AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT RESEARCH UNIT 3702 CURTIN ROAD UNIVERSITY PARK, PA 16802 SUBMITTED BY JOHN SCHMIDT, RESEARCH LEADER POC: PETER KLEINMAN [email protected] NOVEMBER 15, 2011 Introduction We propose to establish an Upper Chesapeake Bay/ Susquehanna River component of the nascent Long Term Agro-ecosystem Research (LTAR) network, with leadership of that component by USDA-ARS Pasture Systems and Watershed Management Research Unit (PSWMRU). To fully represent the Upper Chesapeake Bay/ Susquehanna River region, four watershed locations are identified where intensive research would be focused in each of the major physiographic provinces contained within the region. Due to varied physiographic and biotic zones within the region, multiple watershed sites are required to represent the diversity of agricultural conditions. The PSWMRU has a long history of high-impact research on watershed and grazing land management, and has an established nexus of regional and national collaborative networks that would rapidly expand the linkages desired under LTAR (GRACEnet, the Conservation Effects Assessment Project, the Northeast Pasture Consortium and SERA-17). Research from the PSWMRU underpins state and national agricultural management guidelines (Phosphorus Index, Pasture Conditioning Score Sheet, NRCS practice standards). However, it is the leadership of the PSWMRU in Chesapeake Bay mitigation activities, reflected in the geographic organization of the proposed network by Bay watershed’s physiographic provinces that makes the proposed Upper Chesapeake Bay/ Susquehanna River component an appropriate starting point for the LTAR network. -

Catawissa Creek Watershed: 303(D) Listed Streams and Municipalities

Catawissa Creek Watershed: 303(d) Listed Streams and Municipalities MIFFLIN (2TWP) Scotch Run k ee Cr a ss wi ta Ca o T 41 75 2 ib Tr un h R k MAIN (2TWP) otc ee Sc er Run Cr Beav LL UU ZZ EE RR NN EE CC OO UU NN TT YY a iss ek aw re at C C sa is C aw ata at wi C ssa CC OO LL UU MM BB II AA CC OO UU NN TT YY Cr eek n e Ru BEAVER (2TWP) n rnac n e Ru Fu u rnac r R Fu ve un n ea R Ru B CATAWISSA (BORO) ce er a C rn eav C a a Fu B t t aw CATAWISSA (2TWP) To a Catawissa Cat w is 45 awissa Creek s 5 r Run i a 7 Fishe s C 2 s re rib a e T k C r un e R e er k ish F k n Cree Raccoo FRANKLIN (2TWP) BLACK CREEK (2TWP) un Nuremberg R ap "Long Hollow" G e in ow" T M Holl o ek Long Catawis m oaf Cre " sa Creek h Sugarl reek ic Catawissa C ke Creek en L C ick n ek k h i C re a e om t C e T t r f t r l a a T e o rib C e e rl w 27 a k 565 n k g ree To e C u i C Ca k S s ssa taw i is c r " s taw sa i w C a Cr h o llo a C ee o To k m k r H a 5 o ree nge t 756 o C 2 k n ROARING CREEK (2TWP) Stra C a rib T icke " w T e h r k Tom e d e is re e s C k a ssa R i u C aw HAZLE (2TWP) t n re Ca e sa Creek k ek LL UU ZZ EE RR NN EE CC OO UU NN TT YY f Catawis C Tomhicken Cre ib 27615 O ataw Tr issa L Legend Cr i ee t k t Cat un l awissa Klingermans R NORTH UNION (2TWP) e Creek BANKS (2TWP) T Catawissa Creek o m Towns h n i k y Ru c ee CC AA RR BB OO NN CC OO UU NN TT YY err k Cr anb e ry Cr n do T y rib 2 C k Population Crooked Run 7568 To To un mhicken r H Creek e e k MCADOO (BORO) less than 10,000 k e e r C a 10,000 to 49,999 s s i w McAdoo a t 50,000 to 99,999 a C C a t a w EAST UNION (2TWP) un i Streams ed R s rook s C a C r KLINE (2TWP) e Strahler Stream Order e SS CC HH UU YY LL KK II LL LL CC OO UU NN TT YY k Cataw 1 issa Creek un n ek R u Catawissa Cre M un 2 y R e ers R n on rk ss ess Ru St a er To M rs D s 10 se R 276 es un Trib M 3 Messers Run D . -

Abandoned Mine Drainage Workgroup Overview

ABANDONED MINE DRAINAGE The headwaters of the Schuylkill River are located in the serene mountain valleys of Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. An area rich in scenic beauty and coal mining history, the Little Schuylkill and Upper Schuylkill Rivers are designated cold-water fisheries, and the Schuylkill main stem is a State Scenic River at the confluence of these two tributary waterways. Abandoned Mine Drainage (AMD) is the primary cause of pollution in the Schuylkill River headwaters and the biggest source of metals downstream. AMD is created deep below the ground in abandoned mines where streams, groundwater, and stormwater fill tunnels that were once kept dry by active pumping operations. Water and oxygen react with lingering iron sulfide (pyrite) producing metal-laden and sometimes highly acidic discharges that exit the tunnels in telltale orange and silver plumes, easily visible in these regional surface waters. Abandoned mine discharge Schuylkill PottsvillPottsville River Watershed NJ S Reading ch uy Pottstown lk ill Trenton Riv e Norri r Norristown r PA e iv Philadelphia R Camden re wa N Wilmington la e DE D W E MD S Abandoned mine tunnel AMD interferes with vegetative growth and reproduction of aquatic animals by armoring the streambed with deposits of iron and other metals. Acidity and metals impair both surface and ground drinking water resources and quickly corrode pipes and industrial mechanisms. Unattractive waterways marred by AMD can hinder tourism and recreational opportunities like fishing, boating, and swimming that attract so many people to visit, vacation, and reside in this region. Passive AMD treatment system AMD treatment is expensive, but so is the economic and environmental damage that results from untreated AMD. -

Kayaking • Fishing • Lodging Table of Contents

KAYAKING • FISHING • LODGING TABLE OF CONTENTS Fishing 4-13 Kayaking & Tubing 14-15 Rules & Regulations 16 Lodging 17-19 1 W. Market St. Lewistown, PA 17044 www.JRVVisitors.com 717-248-6713 [email protected] The Juniata River Valley Visitors Bureau thanks the following contributors to this directory. Without your knowledge and love of our waterways, this directory would not be possible. Joshua Hill Nick Lyter Brian Shumaker Penni Abram Paul Wagner Bob Wert Todd Jones Helen Orndorf Ryan Cherry Thankfully, The Juniata River Valley Visitors Bureau Jenny Landis, executive director Buffie Boyer, marketing assistant Janet Walker, distribution manager 2 PAFLYFISHING814 Welcome to the JUNIATA RIVER VALLEY Located in the heart of Central Pennsylvania, the Juniata River Valley, is named for the river that flows from Huntingdon County to Perry County where it meets the Susquehanna River. Spanning more than 100 miles, the Juniata River flows through a picturesque valley offering visitors a chance to explore the area’s wide fertile valleys, small towns, and the natural heritage of the region. The Juniata River watershed is comprised of more than 6,500 miles of streams, including many Class A fishing streams. The river and its tributaries are not the only defining characteristic of our landscape, but they are the center of our recreational activities. From traditional fishing to fly fishing, kayaking to camping, the area’s waterways are the ideal setting for your next fishing trip or family vacation. Come and “Discover Our Good Nature” any time of year! Find Us! The Juniata River Valley is located in Central Pennsylvania midway between State College and Harrisburg. -

Luzerne County Act 167 Phase II Stormwater Management Plan

Executive Summary Luzerne County Act 167 Phase II Stormwater Management Plan 613 Baltimore Drive, Suite 300 Wilkes-Barre, PA 18702 Voice: 570.821.1999 Fax: 570.821.1990 www.borton-lawson.com 3893 Adler Place, Suite 100 Bethlehem, PA 18017 Voice: 484.821.0470 Fax: 484.821.0474 Submitted to: Luzerne County Planning Commission 200 North River Street Wilkes-Barre, PA 18711 June 30, 2010 Project Number: 2008-2426-00 LUZERNE COUNTY STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY – INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction This Stormwater Management Plan has been developed for Luzerne County, Pennsylvania to comply with the requirements of the 1978 Pennsylvania Stormwater Management Act, Act 167. This Plan is the initial county-wide Stormwater Management Plan for Luzerne County, and serves as a Plan Update for the portions or all of six (6) watershed-based previously approved Act 167 Plans including: Bowman’s Creek (portion located in Luzerne County), Lackawanna River (portion located in Luzerne County), Mill Creek, Solomon’s Creek, Toby Creek, and Wapwallopen Creek. This report is developed to document the reasoning, methodologies, and requirements necessary to implement the Plan. The Plan covers legal, engineering, and municipal government topics which, combined, form the basis for implementation of a Stormwater Management Plan. It is the responsibility of the individual municipalities located within the County to adopt this Plan and the associated Ordinance to provide a consistent methodology for the management of stormwater throughout the County. The Plan was managed and administered by the Luzerne County Planning Commission in consultation with Borton-Lawson, Inc. The Luzerne County Planning Commission Project Manager was Nancy Snee. -

Download Proposed Regulation

This space for use by IRRC H f7 .-I""* -*- i t. , ^ ^ (1) Agency Department of Environmental Protection 2m mm ?}mm (2) I.D. Number (Governor's Office Use) #7-366 IRRC Number: J?9BQ> (3) Short Title Stream Redesignations, Class A Wild Trout Waters (4) PA Code Cite (5) Agency Contacts & Telephone Numbers 25 PA Code, Chapter 93 Primary Contact: Sharon F. Trostle, 783-1303 Secondary Contact: Edward R. Brezina, 787-9637 (6) Type of Rulemaking (Check One) (7) Is a 120-Day Emergency Certification Attached? x Proposed Rulemaking X No Final Order Adopting Regulation Yes: By the Attorney General Final Order, Proposed Rulemaking Omitted Yes: By the Governor (8) Briefly explain the regulation in clear and nontechnical language This proposed rulemaking modifies Chapter 93 to reflect the recommended redesignation of a number of streams that are designated as Class A Wild Trout Waters by the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC). Class A Waters qualify for designation as High Quality Waters (HQ) under §§ 93.4b(a)(2)(ii). The changes provide the appropriate designated use to these streams to protect existing uses. These changes may, upon implementation, result in more stringent treatment requirements for new and/or expanded wastewater discharges to the streams in order to protect the existing and designated water uses. (9) State the statutory authority for the regulation and any relevant state or federal court decisions. These proposed amendments are made under the authority of the following acts: The Pennsylvania Clean Streams Law, Act of June 22, 1937 (P.L. 1987, No 394) as amended, 35 P.S/S 691.5 etseq. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Shoup's Run Watershed Association

11/1/2004 Shoup Run Watershed Restoration Plan Developed by the Huntingdon County Conservation District for The Shoup Run Watershed Association Introduction Watershed History The Shoup Run, locally known as Shoup’s Run, watershed drains approximately 13,746 acres or 21.8 square miles, in the Appalachian Mountain, Broad Top region of the Valley-Ridge Physiographic Province. Within this province, the area lies within the northwestern section of the Broad Top Mountain Plateau. This area is characterized by narrow valleys and moderately steep mountain slopes. Shoup Run is located in Huntingdon County, but includes drainage from portions of Bedford County. Shoup Run flows into the Raystown Branch of the Juniata River near the community of Saxton at river mile 42.4. Shoup Run has five named tributaries (Figure 1). Approximately 10% of the surface area of the Shoup Run basin has been surface mined. Much of the mining activity was done prior to current regulations and few of the mines were reclaimed to current specifications. Surface mining activity ended in the early 1980’s. There is currently no active mining in the watershed. Deep mines underlie approximately 12% of the Shoup Run watershed. Many abandoned deep mine entries and openings still exist in the Shoup Run Basin. Deep mining was done below the water table in many locations. In order to dewater the mines, drifts were driven into the deep mines to allow water to flow down slope and out of many of the mines. The bedrock in this area is folded and faulted. Tunnels were driven through many different lithologies to allow drainage. -

Pine Knot Mine Drainage Tunnel –

QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF STREAM WATER DRAINING MINED AREAS OF THE UPPER SCHUYLKILL RIVER BASIN, SCHUYLKILL COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA, USA, 2005-20071 Charles A. Cravotta III,2 and John M. Nantz Abstract: Hydrologic effects of abandoned anthracite mines were documented by continuous streamflow gaging coupled with synoptic streamflow and water- quality monitoring in headwater reaches and at the mouths of major tributaries in the upper Schuylkill River Basin, Pa., during 2005-2007. Hydrograph separation of the daily average streamflow for 10 streamflow-gaging stations was used to evaluate the annual streamflow characteristics for October 2005 through September 2006. Maps showing stream locations and areas underlain by underground mines were used to explain the differences in total annual runoff, base flow, and streamflow yields (streamflow/drainage area) for the gaged watersheds. For example, one stream that had the lowest yield (59.2 cm/yr) could have lost water to an underground mine that extended beneath the topographic watershed divide, whereas the neighboring stream that had the highest yield (97.3 cm/yr) gained that water as abandoned mine drainage (AMD). Although the stream-water chemistry and fish abundance were poor downstream of this site and others where AMD was a major source of streamflow, the neighboring stream that had diminished streamflow met relevant in-stream water-quality criteria and supported a diverse fish community. If streamflow losses could be reduced, natural streamflow and water quality could be maintained in the watersheds with lower than normal yields. Likewise, stream restoration could lead to decreases in discharges of AMD from underground mines, with potential for decreased metal loading and corresponding improvements in downstream conditions. -

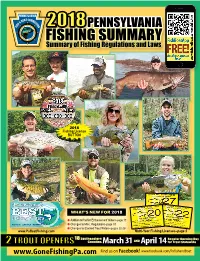

2018 Pennsylvania Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws PERMITS, MULTI-YEAR LICENSES, BUTTONS

2018PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws 2018 Fishing License BUTTON WHAT’s NeW FOR 2018 l Addition to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 l Changes to Misc. Regulations–page 16 l Changes to Stocked Trout Waters–pages 22-29 www.PaBestFishing.com Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 31 AND April 14 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the LOCATION PFBC S/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. THANK YOU FOR MORE INFORMATION: for the purchase STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: license! Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish and Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: Commonwealth’s aquatic resources EDUCATION COURSES FOLLOW US: www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. REGION OFFICES: LAW ENFORCEMENT/EDUCATION Contents Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating opportunities. Contact Education for information about fishing and boating programs and boating safety education.