Building AP Music Theory Skills from the Ground Up

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medicine Health

Medicine Health RHODEI SLAND VOL. 85 NO. 1 JANUARY 2002 Cancer Update A CME Issue UNDER THE JOINT VOLUME 85, NO. 1 JANUARY, 2002 EDITORIAL SPONSORSHIP OF: Medicine Health Brown University School of Medicine Donald Marsh, MD, Dean of Medicine HODE SLAND & Biological Sciences R I Rhode Island Department of Health PUBLICATION OF THE RHODE ISLAND MEDICAL SOCIETY Patricia Nolan, MD, MPH, Director Rhode Island Quality Partners Edward Westrick, MD, PhD, Chief Medical Officer Rhode Island Chapter, American College of COMMENTARIES Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine Fred J. Schiffman, MD, FACP, Governor 2 Demented Politicians Rhode Island Medical Society Joseph H. Friedman, MD Yul D. Ejnes, MD, President 3 Some Comments On a Possible Ancestor EDITORIAL STAFF Stanley M. Aronson, MD, MPH Joseph H. Friedman, MD Editor-in-Chief Joan M. Retsinas, PhD CONTRIBUTIONS Managing Editor CANCER UPDATE: A CME ISSUE Hugo Taussig, MD Guest Editor: Paul Calabresi, MD, MACP Betty E. Aronson, MD Book Review Editors 4 Cancer in the New Millennium Stanley M. Aronson, MD, MPH Paul Calabresi, MD, MACP Editor Emeritus 7 Update in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer EDITORIAL BOARD Betty E. Aronson, MD Todd Moore, MD, and Neal Ready, MD, PhD Stanley M. Aronson, MD 10 Breast Cancer Update Edward M. Beiser, PhD, JD Mary Anne Fenton, MD Jay S. Buechner, PhD John J. Cronan, MD 14 Screening for Colorectal Cancer in Rhode Island James P. Crowley, MD Arvin S. Glicksman, MD John P. Fulton, PhD Peter A. Hollmann, MD 17 Childhood Cancer: Past Successes, Future Directions Anthony Mega, MD William S. Ferguson, MD, and Edwin N. -

Simple Gifts

Excerpts from . DEVELOPING MUSICIANSHIP THROUGH IMPROVISATION Simple Gifts Christopher D. Azzara Eastman School of Music of the University of Rochester Richard F. Grunow Eastman School of Music of the University of Rochester GIA Publications, Inc. Chicago Developing Musicianship through Improvisation Christopher D. Azzara Richard F. Grunow Layout and music engravings: Paul Burrucker Copy editor: Elizabeth Bentley Copyright © 2006 GIA Publications, Inc. 7404 S. Mason Ave., Chicago 60638 www.giamusic.com All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 2 INTRODUCTION Do you know someone who can improvise? Chances are he or she knows a lot of tunes and learns new tunes with relative ease. It seems that improvisers can sing and/or play anything that comes to mind. Improvisers interact in the moment to create one-of-a-kind experiences. Many accomplished musicians do not think of themselves as improvisers, yet if they have something unique to say in their performance, they are improvisers. In that sense, we are all improvisers, and it is important to have opportunities throughout our lives to express ourselves creatively through improvisation. Improvisation in music is the spontaneous expression of meaningful musical ideas—it is analogous to conversation in language. As presented here, key elements of improvisation include personalization, spontaneity, anticipation, prediction, interaction, and being in the moment. Interestingly, we are born improvisers, as evidenced by our behavior in early childhood. This state of mind is clearly demonstrated in children’s play. When not encouraged to improvise as a part of our formal music education, the very thought of improvisation invokes fear. If we let go of that fear, we find that we are improvisers. -

Stephen Brien

AN INVESTIGATION OF FORWARD MOTION AS AN ANALYTIC TEMPLATE (~., ·~ · · STEPHEN BRIEN A THESIS S B~LITTED I P RTIAL F LFLLLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF M IC PERFORMANCE SYDNEY CONSERV ATORIUM OF MUSIC UN IVERSITY OF SYDNEY 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to thank Dick Montz, Craig Scott, Phil Slater and Dale Barlow for their support and encouragement in the writing of this thesis. :.~~,'I 1 lt,·,{l ((.. v <'oo'5 ( ., '. ,. ~.r To Hal Galper ABSTRACT Investigati on of Forward Motion as an analytic templ ate extracts the elements of Forward Motion as expounded in jazz pianist Hal Gal per's book- Forward Motion .from Bach to Bebop; a Corrective Approach to Jazz Phrasing and uses these element s as an analyt ic template wi th which to assess fo ur solos of Australian jazz musician Dale Barlow. This case study includes a statistical analysis of the Forward Motion elements inherent in Barlow' s improvisi ng, whi ch provides an interesting insight into how much of Galp er' s educational theory exists within the playing of a mu sician un fa miliar with Galper ' s methods. TABLES CONT ... 9. Table 2G 2 10. Table 2H 26 II . Table21 27 12. Table 2J 28 13 . Table2K 29 14. Table 2L 30 15. Table 2M 3 1 16. Table 2N 32 17. Table 20 33 18. Table 2P 35 19. Table 2Q 36 Angel Eyes I. Table lA 37 2. Table IB 37 3. Table 2A 38 4. Table 2B 40 5. Table 2C 42 6. -

S Y N C O P a T I

SYNCOPATION ENGLISH MUSIC 1530 - 1630 'gentle daintie sweet accentings1 and 'unreasonable odd Cratchets' David McGuinness Ph.D. University of Glasgow Faculty of Arts April 1994 © David McGuinness 1994 ProQuest Number: 11007892 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007892 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 10/ 0 1 0 C * p I GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ERRATA page/line 9/8 'prescriptive' for 'proscriptive' 29/29 'in mind' inserted after 'his own part' 38/17 'the first singing primer': Bathe's work was preceded by the short primers attached to some metrical psalters. 46/1 superfluous 'the' deleted 47/3,5 'he' inserted before 'had'; 'a' inserted before 'crotchet' 62/15-6 correction of number in translation of Calvisius 63/32-64/2 correction of sense of 'potestatis' and case of 'tactus' in translation of Calvisius 69/2 'signify' sp. 71/2 'hierarchy' sp. 71/41 'thesis' for 'arsis' as translation of 'depressio' 75/13ff. Calvisius' misprint noted: explanation of his alterations to original text clarified 77/18 superfluous 'themselves' deleted 80/15 'thesis' and 'arsis' reversed 81/11 'necessary' sp. -

Glossary of Musical Terms

GLOSSARY OF MUSICAL TERMS A absolute music: instrumental music with no intended story (non-programmatic music) a cappella: choral music with no instrumental accompaniment accelerando: gradually speeding up the speed of the rhythmic beat accent: momentarily emphasizing a note with a dynamic attack accessible: music that is easy to listen to and understand adagio: a slow tempo alla breve / cut time: a meter with two half-note beats per measure. It’s often symbolized by the cut-time symbol allegro: a fast tempo; music should be played cheerfully / upbeat brisk alto: a low-ranged female voice; the second highest instrumental range alto instrument examples: alto flute, viola, French horn, natural horn, alto horn, alto saxophone, English horn andante: moderate tempo (a walking speed; "Andare" means to walk) aria: a beautiful manner of solo singing, accompanied by orchestra, with a steady metrical beat articulation marks: Normal: 100% Staccato: 50% > Accent: 75% ^ Marcato: 50% with more weight on the front - Tenuto: 100% art-music: a general term used to describe the "formal concert music" traditions of the West, as opposed to "popular" and "commercial music" styles art song: a musical setting of artistic poetry for solo voice accompanied by piano (or orchestra) atonal: music that is written and performed without regard to any specific key atonality: modern harmony that intentionally avoids a tonal center (has no apparent home key) augmentation: lengthening the rhythmic values of a fugal subject avant-garde: ("at the forefront") a French term that describes highly experimental modern musical styles B ballad: a work in dance form imitative of a folk song, with a narrative structure ballet: a programmatic theatrical work for dancers and orchestra bar: a common term for a musical measure barcarolle: a boating song, generally describing the songs sung by gondoliers in Venice. -

A Study of Compositional Elements in Ciclo Brasileiro by Heitor Villa- Lobos

A STUDY OF COMPOSITIONAL ELEMENTS IN CICLO BRASILEIRO BY HEITOR VILLA- LOBOS Maria Eduarda Lucena Vieira A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2017 Committee: Gene Trantham, Advisor Yu-Lien The ii ABSTRACT Gene Trantham, Advisor Heitor Villa-Lobos, a well-known Brazilian composer, was born in the city of Rio de Janeiro, in 1887, the same place where he died, in 1959. He was influenced by many composers not only from Brazil, but also from around the world, such as Debussy, Igor Stravinsky and Darius Milhaud. Even though Villa-Lobos spent most of his life traveling to Europe and the United States, his works always had a Brazilian musical flavor. This thesis will focus on the Ciclo Brasileiro (Brazilian Cycle) written for piano in 1936. The premiere of this set was initially presented in 1938 as individual pieces including “Impressões Seresteiras” (The Impressions of a Serenade) and “Dança do Indio Branco” (Dance of the White Indian). The other pieces of the set, “Plantio do Caboclo” (The Peasant’s Sowing) and “Festa no Sertão” (The Fete in the Desert) were premiered in 1939. Both performances occurred in Rio de Janeiro. Also in 1936 he wrote two other pieces, “Bazzum”, for men’s voices and Modinhas e canções (Folk Songs and Songs), album 1. My thesis will explore Heitor Villa-Lobos’ Ciclo Brasileiro and hopefully will find direct or indirect elements of the Brazilian culture. In chapter 1, I will present an introduction including Villa-Lobos’ background about his life and music, and how classical and folk influences affected his compositional process in the Ciclo Brasileiro. -

Melodic Pattern Segmentation of Polyphonic Music As a Set Partitioning Problem Tsubasa Tanaka, Koichi Fujii

Melodic Pattern Segmentation of Polyphonic Music as a Set Partitioning Problem Tsubasa Tanaka, Koichi Fujii To cite this version: Tsubasa Tanaka, Koichi Fujii. Melodic Pattern Segmentation of Polyphonic Music as a Set Partitioning Problem. International Congress on Music and Mathematics, Nov 2014, Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. hal- 01467889 HAL Id: hal-01467889 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01467889 Submitted on 14 Feb 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Melodic Pattern Segmentation of Polyphonic Music as a Set Partitioning Problem Tsubasa Tanaka and Koichi Fujii Abstract In polyphonic music, melodic patterns (motifs) are frequently imitated or repeated, and transformed versions of motifs such as inversion, retrograde, augmen- tations, diminutions often appear. Assuming that economical efficiency of reusing motifs is a fundamental principle of polyphonic music, we propose a new method of analyzing a polyphonic piece that economically divides it into a small number of types of motif. To realize this, we take an integer programming-based approach and formalize this problem as a set partitioning problem, a well-known optimiza- tion problem. This analysis is helpful for understanding the roles of motifs and the global structure of a polyphonic piece. -

Identification and Analysis of Wes Montgomery's Solo Phrases Used in 'West Coast Blues'

Identification and analysis of Wes Montgomery's solo phrases used in ‘West Coast Blues ’ Joshua Hindmarsh A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music The University of Sydney 2016 Declaration I, Joshua Hindmarsh hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person except for the co-authored publication submitted and where acknowledged in the text. This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of a higher degree. Signed: Date: 4/4/2016 Acknowledgments I wish to extend my sincere gratitude to the following people for their support and guidance: Mr Phillip Slater, Mr Craig Scott, Prof. Anna Reid, Mr Steve Brien, and Dr Helen Mitchell. Special acknowledgement and thanks must go to Dr Lyle Croyle and Dr Clare Mariskind for their guidance and help with editing this research. I am humbled by the knowledge of such great minds and the grand ideas that have been shared with me, without which this thesis would never be possible. Abstract The thesis investigates Wes Montgomery's improvisational style, with the aim of uncovering the inner workings of Montgomery's improvisational process, specifically his sequencing and placement of musical elements on a phrase by phrase basis. The material chosen for this project is Montgomery's composition 'West Coast Blues' , a tune that employs 3/4 meter and a variety of chordal backgrounds and moving key centers, and which is historically regarded as a breakthrough recording for modern jazz guitar. -

Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: a Hierarchical Approach Author(S): Timothy A

Yale University Department of Music Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: A Hierarchical Approach Author(s): Timothy A. Johnson Source: Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Spring, 1993), pp. 117-156 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of the Yale University Department of Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/843946 Accessed: 06-07-2017 19:50 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Yale University Department of Music, Duke University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Music Theory This content downloaded from 198.199.32.254 on Thu, 06 Jul 2017 19:50:30 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms HARMONIC VOCABULARY IN THE MUSIC OF JOHN ADAMS: A HIERARCHICAL APPROACH Timothy A. Johnson Overview Following the minimalist tradition, much of John Adams's' music consists of long passages employing a single set of pitch classes (pcs) usually encompassed by one diatonic set.2 In many of these passages the pcs form a single diatonic triad or seventh chord with no additional pcs. In other passages textural and registral formations imply a single triad or seventh chord, but additional pcs obscure this chord to some degree. -

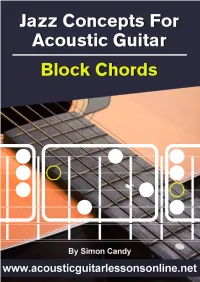

Jazz Concepts for Acoustic Guitar Block Chords

Jazz Concepts For Acoustic Guitar Block Chords © Guitar Mastery Solutions, Inc. Page !2 Table Of Contents A Little Jazz? 4 What Are Block Chords? 4 Chords And Inversions 5 The 3 Main Block Chord Types And How They Fit On The Fretboard 6 Major 7th ...................................................................................6 Dominant 7th ..............................................................................6 Block Chord Application 1 - Blues 8 Background ................................................................................8 Organising Dominant Block Chords On The Fretboard .......................8 Blues Example ...........................................................................10 Block Chord Application 2 - Neighbour Chords 11 Background ...............................................................................11 The Progression .........................................................................11 Neighbour Chord Example ...........................................................12 Block Chord Application 3 - Altered Dominant Block Chords 13 Background ...............................................................................13 Altered Dominant Chord Chart .....................................................13 Altered Dominant Chord Example .................................................15 What’s Next? 17 © Guitar Mastery Solutions, Inc. Page !3 A Little Jazz? This ebook is not necessarily for jazz guitar players. In fact, it’s more for acoustic guitarists who would like to inject a little -

Differentiating ERAN and MMN: an ERP Study

NEUROPHYSIOLOGY, BASIC AND CLINICAL NEUROREPORT Differentiating ERAN and MMN: An ERP study Stefan Koelsch,1,CA Thomas C. Gunter,1 Erich SchroÈger,2 Mari Tervaniemi,3 Daniela Sammler1,2 and Angela D. Friederici1 1Max Planck Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, Stephanstr. 1a, D-04103 Leipzig; 2Institute of General Psychology, Leipzig, Germany; 3Cognitive Brain Research Unit, Helsinki, Finland CACorresponding Author Received 14 February 2001; accepted 27 February 2001 In the present study, the early right-anterior negativity (ERAN) both a longer latency, and a larger amplitude. The combined elicited by harmonically inappropriate chords during listening ®ndings indicate that ERAN and MMN re¯ect different mechan- to music was compared to the frequency mismatch negativity isms of pre-attentive irregularity detection, and that, although (MMN) and the abstract-feature MMN. Results revealed that both components have several features in common, the ERAN the amplitude of the ERAN, in contrast to the MMN, is does not easily ®t into the classical MMN framework. The speci®cally dependent on the degree of harmonic appropriate- present ERPs thus provide evidence for a differentiation of ness. Thus, the ERAN is correlated with the cognitive cognitive processes underlying the fast and pre-attentive processing of complex rule-based information, i.e. with the processing of auditory information. NeuroReport 12:1385±1389 application of music±syntactic rules. Moreover, results showed & 2001 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. that the ERAN, compared to the abstract-feature MMN, had Key words: Auditory processing; EEG; ERAN; ERP; MMN; Music INTRODUCTION not a frequency MMN which is known to be elicited only Accurate pitch perception is a prerequisite for the proces- when a deviant tone, or chord, is preceded by a few sing of melodic, harmonic, and prosodic aspects of both standard tones or chords with identical frequency [8,9]. -

Chapter 3.2.1 That Non-Tonal Improvisation Is a Very Relative Term Because Any Configuration of Notes Can Be Identified by Root Oriented Chord Symbols

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/57415 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Graaf, Dirk Pieter de Title: Beyond borders : broadening the artistic palette of (composing) improvisers in jazz Date: 2017-11-21 3. IMPROVISING WITH JAZZ MODELS 3.1 Introduction 3.1.1 The chord-scale technique Through the years, a large number of educational methods on how to improvise in jazz have been published (for instance Oliver Nelson 1966; Jerry Coker, Jimmy Casale, Gary Campbell and Jerry Greene 1970; Bunky Green 1985; David Baker 1988; Hal Crook 1991; Jamey Aebershold 2010). The instructions and examples in these publications are basically meant to develop the musician’s skills in chord-scale improvisation, which is generally considered as the basis of linear improvisation in functional and modal harmonies. In section 1.4.1, I have already discussed my endeavors to broaden my potential to play “outside” the stated chord changes, as one of the ingredients that would lead to a personal sound. Although few of the authors mentioned above have discussed comprehensive techniques of creating “alternative” jazz languages beyond functional harmony, countless jazz artists have developed their individual theories and strategies of “playing outside”, as an alternative to or an extension of their conventional linear improvisational languages. Although in the present study the melodic patterns often sound “pretty far out”, I agree with David Liebman’s thinking pointed out in section 2.2.1, that improvised lines are generally related to existing or imaginary underlying chords. Unsurprisingly, throughout this study the chord-scale technique as a potential way to address melodic improvisation will occasionally emerge.