The Privatization of Alitalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Skyteam Timetable Covers Period: 01 Jun 2021 Through 31 Aug 2021

SkyTeam Timetable Covers period: 01 Jun 2021 through 31 Aug 2021 Regions :Europe - Asia Pacific Contact Disclaimer To book, contact any SkyTeam member airline. The content of this PDF timetable is for information purposes only, subject to change at any time. Neither Aeroflot www.aeroflot.com SkyTeam, nor SkyTeam Members (including without Aerolneas Argentinas www.aerolineas.com limitation their respective suppliers) make representation Aeromexico www.aeromexico.com or give warranty as to the completeness or accuracy of Air Europa www.aireuropa.com such content as well as to its suitability for any purpose. Air France www.airfrance.com In particular, you should be aware that this content may be incomplete, may contain errors or may have become Alitalia www.alitalia.com out of date. It is provided as is without any warranty or China Airlines www.china-airlines.com condition of any kind, either express or implied, including China Eastern www.ceair.com but not limited to all implied warranties and conditions of China Southern www.csair.com merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, title and Czech Airlines www.czechairlines.com non-infringement. Given the flexible nature of flight Delta Air Lines www.delta.com schedules, our PDF timetable may not reflect the latest information. Garuda Indonesia www.garuda-indonesia.com Kenya Airways www.kenya-airways.com By accessing the PDF timetable, the user acknowledges that the SkyTeam Alliance and any SkyTeam member KLM www.klm.com airline will not be responsible or liable to the user, or any -

What Next for Alitalia After Air France-KLM Snub? Is Not a Normal Aircraft,” He Said

ISSN 1718-7966 SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 / VOL. 408 WEEKLY AVIATION HEADLINES Read by thousands of aviation professionals and technical decision-makers every week www.avitrader.com WORLD NEWS Lion Air in CSeries talks Lion Air, the Indonesian budget carrier, is in talks with Canadian airframer Bombardier over a po- Alitalia is facing a cash tential order for up to 100 of its crunch after larger CSeries CS300 jets, with major share- negotiations set to be finalised holder Air at the UK’s Farnborough Airshow France-KLM voted against next July. In meetings with Bom- a capital bardier Commercial Aircraft boss increase Mike Arcamone last week, Lion Air president Rusdi Karana said Alitalia the CSeries was ‘beyond his ex- pectation: “What they’re doing What next for Alitalia after Air France-KLM snub? is not a normal aircraft,” he said. Move to keep carrier under Italian control would be ‘hidden nationalization’ “This one is very special.” It is understood that Export Develop- The future is looking increasingly with its own internal troubles, last Industry minister Flavio Zamonato ment Canada would be involved grim for Italian flag carrier Alita- week announcing that it no long- told reporters that the government in financing the deal. lia after Air France-KLM, its larg- er expected to reach its break- was in talks with banks and other est shareholder, last week voted even target this year and that it investors in the domestic market $15.6bn for Airbus in China against proposals to launch a would slash a further 2,800 jobs. that would keep the company un- capital increase of at Airbus said it won orders worth der Italian control. -

Covid-Tested Flights

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board A virtual w orkshop – February 4-5, 2021 Aeroporti di Roma and the Italian Government’s actions to ensure health safety during the Pandemic Ivan Bassato Executive Vice President of Operations Aeroporti di Roma at a glance – In the Pre-Covid era Aeroporti di Roma – ADR – operates the two airports of Rome (Fiumicino FCO and Ciampino CIA). Total passengers in 2019: 49,4 mln (26% of all passengers in Italy) With 43,5 mln passengers in 2019, Rome Fiumicino is a major hub airport in Europe. About Rome FCO airport 100 airlines connect Rome to 200+ destinations. has been awarded More than 50 long haul destinations, including 12 major cities in China as «Best Airport in In 2019, 3,4 mln passengers between North America and Rome. Up to 24 daily Europe» in 2018, 2019 and departures serving the US market (2,8 mln pax). 600K pax between Canada and Rome. 2020 Fully committed to top quality service and safety 2 Covid-19 pandemic trends in Italy, in the EU and in the USA In 2020: • January 30-31, all direct flights to China suspended. State of emergency declared. • February 21, first case locally transmitted in Northern Italy, first Prevention measures “red zones” and schools closures for transport, work • March 9, National lockdown. Until and social spaces May 4. Then gradual lifting, but mainly established in this period social distancing and mask obligation for indoor spaces stay since then. • Summer 20, focus on imported cases • Autumn-Winter -

Air France KLM Martinair Cargo and Bolloré Logistics Team up to Launch the First Low-Carbon Airfreight Route Between France and the United States

Press release Puteaux, 21 January 2021 Air France KLM Martinair Cargo and Bolloré Logistics team up to launch the first low-carbon airfreight route between France and the United States Bolloré Logistics has joined the Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) programme of Air France KLM Martinair Cargo (AFKLMP Cargo) for its 2021 shipments between Paris Charles de Gaulle and New York John F. Kennedy airports. This first of its kind collaboration illustrates the ambition of these two historical partners to tackle the environmental challenge of airfreight transportation. Christophe Boucher, EVP Air France Cargo says: “The Cargo SAF Programme enables shippers and forwarders to power a percentage of their flights with SAF. Customers determine their own level of engagement and we ensure that their entire investment is used for sourcing SAF. I’m delighted to see the speed at which Air France KLM Martinair Cargo and Bolloré Logistics have come to an agreement on the use of our SAF programme, launched a few weeks ago. I’m proud that together we are trendsetters in a field that will grow in our companies and in society.” This innovative aviation fuel will cut CO₂ emissions by at least 50% on airfreight shipped by Bolloré Logistics on this symbolic trade lane. Investing in this strategic route represents a new step towards achieving greater sustainability in the future for both Bolloré Logistics and AFKLMP Cargo. “Reducing carbon emissions is a major challenge in the airfreight transportation industry and Bolloré Logistics is committed to addressing this with innovative solutions. In 2021, the company has committed itself to reducing scope 3 CO₂ emissions linked to the performance of its transport services by 30% by 2030. -

Agent Debit Memo (Adm) Policy Alitalia

AGENT DEBIT MEMO (ADM) POLICY ALITALIA LEGAL HEAD OFFICE Via A.Nassetti Share Capital € 103,105,126.99 fully paid- ALFA Building 00054 Fiumicino (RM) up with registered office in Fiumicino Italia Tel. [+39] 06 6563 1 (RM) Tax ID, Vat Code and registration number in the Companies Register of Rome 13029381004, Rome Economic and Administrative Register n.1418603 ALITALIA AGENCY DEBIT MEMO (ADM) POLICY Revision date 1 January 2017 Dear Agent, With this document ALITALIA (from now on referred to as Carrier) publishes the updated policy on AGENCY DEBIT MEMO (ADM), with reference to the provisions of IATA Resolutions 850m and 818g dated 01 June 2014. This notice replaces any prior notices with effect from 1 January 2017. PREAMBLE Please be reminded that Agents are responsible for properly issuing tickets, consistently with the applicable fares, fare rules and general conditions of carriage and with the instructions received from Carrier. Travel Agents' obligations are set out in the IATA Resolution 824. Agent is invited to inform passengers that Carrier reserves the right to carry out inspections concerning the use of tickets and to demand, if necessary, the payment of the difference between the fare paid and the applicable fare. If passenger refuses boarding may be denied. Agent should also inform passengers that Carrier will honour flight vouchers only when correctly used, following the right sequence and from the point of origin, as per the fare calculation on the ticket. Therefore, any irregular use of ticket or flight coupons sequence will invalidate the travel document. In case of flight / date / booking class change after ticket issuance, whenever the payment of a supplement and/or penalty is required, the relevant ticket must be reissued. -

New Expanded Joint Venture

Press Release The Power of Choice for Cargo Customers as Air France-KLM, Delta and Virgin Atlantic launch trans-Atlantic Joint Venture AMSTERDAM/PARIS, ATLANTA and LONDON: February 3rd, 2020 – Air France-KLM Cargo, Delta Air Lines Cargo and Virgin Atlantic Cargo are promising cargo customers more connections, greater shipment routing flexibility, improved trucking options, aligned services and innovative digital solutions with the launch of their expanded trans-Atlantic Joint Venture (JV). The new partnership, which represents 23% of total trans-Atlantic cargo capacity or more than 600,000 tonnes annually, will enable the airlines to offer the best-ever customer experience, and a combined network of up to 341 peak daily trans-Atlantic services – a choice of 110 nonstop routes with onward connections to 238 cities in North America, 98 in Continental Europe and 16 in the U.K. More choice and convenience for customers Customers will be able to leverage an enhanced network built around the airlines’ hubs in Amsterdam, Atlanta, Boston, Detroit, London Heathrow, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York-JFK, Paris, Seattle and Salt Lake City. It creates convenient nonstop or one-stop connections to every corner of North America, Europe and the U.K., giving customers the added confidence of delivery schedules being met by a wide choice of options. The expanded JV enables greater co-operation between the airlines, focused on delivering world class customer service and reliability on both sides of the Atlantic achieved through co-located facilities, joint trucking options as well as seamless bookings and connected service recovery. The airlines already co-locate at warehouses in key U.S., U.K. -

European Air Law Association 23Rd Annual Conference Palazzo Spada Piazza Capo Di Ferro 13, Rome

European Air Law Association 23rd Annual Conference Palazzo Spada Piazza Capo di Ferro 13, Rome “Airline bankruptcy, focus on passenger rights” Laura Pierallini Studio Legale Pierallini e Associati, Rome LUISS University of Rome, Rome Rome, 4th November 2011 Airline bankruptcy, focus on passenger rights Laura Pierallini Air transport and insolvencies of air carriers: an introduction According to a Study carried out in 2011 by Steer Davies Gleave for the European Commission (entitled Impact assessment of passenger protection in the event of airline insolvency), between 2000 and 2010 there were 96 insolvencies of European airlines operating scheduled services. Of these insolvencies, some were of small airlines, but some were of larger scheduled airlines and caused significant issues for passengers (Air Madrid, SkyEurope and Sterling). Airline bankruptcy, focus on passenger rights Laura Pierallini The Italian market This trend has significantly affected the Italian market, where over the last eight years, a number of domestic air carriers have experienced insolvencies: ¾Minerva Airlines ¾Gandalf Airlines ¾Alpi Eagles ¾Volare Airlines ¾Air Europe ¾Alitalia ¾Myair ¾Livingston An overall, since 2003 the Italian air transport market has witnessed one insolvency per year. Airline bankruptcy, focus on passenger rights Laura Pierallini The Italian Air Transport sector and the Italian bankruptcy legal framework. ¾A remedy like Chapter 11 in force in the US legal system does not exist in Italy, where since 1979 special bankruptcy procedures (Amministrazione Straordinaria) have been introduced to face the insolvency of large enterprises (Law. No. 95/1979, s.c. Prodi Law, Legislative Decree No. 270/1999, s.c. Prodi-bis, Law Decree No. 347/2003 enacted into Law No. -

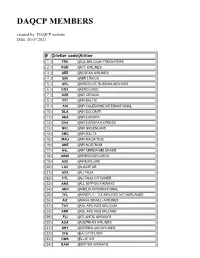

DAQCP MEMBERS Created By: DAQCP Website Date: 20.07.2021

DAQCP MEMBERS created by: DAQCP website Date: 20.07.2021 # 3-letter code Airline 1 FRH ACE BELGIUM FREIGHTERS 2 RUN ACT AIRLINES 3 AEE AEGEAN AIRLINES 4 EIN AER LINGUS 5 AFL AEROFLOT RUSSIAN AIRLINES 6 BOX AEROLOGIC 7 KZR AIR ASTANA 8 BTI AIR BALTIC 9 ACI AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 10 DLA AIR DOLOMITI 11 AEA AIR EUROPA 12 OVA AIR EUROPA EXPRESS 13 GRL AIR GREENLAND 14 AMC AIR MALTA 15 MAU AIR MAURITIUS 16 ANE AIR NOSTRUM 17 ASL AIR SERBIA BELGRADE 18 ABW AIRBRIDGECARGO 19 AXE AIREXPLORE 20 LAV ALBASTAR 21 AZA ALITALIA 22 CYL ALITALIA CITYLINER 23 ANA ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS 24 AEH AMELIA INTERNATIONAL 25 TFL ARKEFLY - TUI AIRLINES NETHERLANDS 26 AIZ ARKIA ISRAELI AIRLINES 27 TAY ASL AIRLINES BELGIUM 28 ABR ASL AIRLINES IRELAND 29 FLI ATLANTIC AIRWAYS 30 AUA AUSTRIAN AIRLINES 31 AHY AZERBAIJAN AIRLINES 32 CFE BA CITYFLYER 33 BMS BLUE AIR 34 BAW BRITISH AIRWAYS 35 BEL BRUSSELS AIRLINES 36 GNE BUSINESS AVIATION SERVICES GUERNSEY LTD 37 CLU CARGOLOGICAIR 38 CLX CARGOLUX AIRLINES INTERNATIONAL S.A 39 ICV CARGOLUX ITALIA 40 CEB CEBU PACIFIC 41 BCY CITYJET 42 CFG CONDOR FLUGDIENST GMBH 43 CTN CROATIA AIRLINES 44 CSA CZECH AIRLINES 45 DLH DEUTSCHE LUFTHANSA 46 DHK DHL AIR LTD. 47 EZE EASTERN AIRWAYS 48 EJU EASYJET EUROPE 49 EZS EASYJET SWITZERLAND 50 EZY EASYJET UK 51 EDW EDELWEISS AIR 52 ELY EL AL 53 UAE EMIRATES 54 ETH ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 55 ETD ETIHAD AIRWAYS 56 MMZ EUROATLANTIC 57 BCS EUROPEAN AIR TRANSPORT 58 EWG EUROWINGS 59 OCN EUROWINGS DISCOVER 60 EWE EUROWINGS EUROPE 61 EVE EVELOP AIRLINES 62 FIN FINNAIR 63 FHY FREEBIRD AIRLINES 64 GJT GETJET AIRLINES 65 GFA GULF AIR 66 OAW HELVETIC AIRWAYS 67 HFY HI FLY 68 HBN HIBERNIAN AIRLINES 69 HOP HOP! 70 IBE IBERIA 71 ICE ICELANDAIR 72 ISR ISRAIR AIRLINES 73 JAL JAPAN AIRLINES CO. -

Case No COMP/JV.19 - */*** KLM / ALITALIA

EN Case No COMP/JV.19 - */*** KLM / ALITALIA Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 11/08/1999 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 399J0019 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 11.08.1999 PUBLIC VERSION MERGER PROCEDURE ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION In the published version of this decision, some information has been omitted pursuant to Article 17(2) of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and other confidential information. The omissions are shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. to the notifying parties Dear Sirs, Subject: Case M/JV-19 KLM-Alitalia Notification of 29 June 1999 pursuant to Article 4 of Regulation N°4064/89 1. On 29 June 1999, the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EEC) No. 4064/891 as last amended by Regulation (EC) No. 1310/972 (the Merger Regulation) by which the undertakings Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij N.V. (KLM) and Alitalia Linee Aeree Italiane S.p.A. (Alitalia) will constitute a Joint Venture under the meaning of Article 3 (2) of the Merger Regulation. 2. In the course of the proceedings, the parties submitted undertakings designed to eliminate competition concerns identified by the Commission, in accordance with Article 6(2) of the Merger Regulation. After examination of the notification and in the light of these modifications, the Commission has concluded that the operation 1 OJ L 395, 30.12.1989, p.1; corrigendum OJ L 257, 21.9.1990, p.13 2 OJ L 180, 9.7.1997, p.1; corrigendum OJ L 40, 13.2.1998, p.17 Rue de la Loi 200, B-1049 Bruxelles/Wetstraat 200, B-1049 Brussel - Belgium Telephone: exchange 299.11.11. -

Airline Alliances

AIRLINE ALLIANCES by Paul Stephen Dempsey Director, Institute of Air & Space Law McGill University Copyright © 2011 by Paul Stephen Dempsey Open Skies • 1992 - the United States concluded the first second generation “open skies” agreement with the Netherlands. It allowed KLM and any other Dutch carrier to fly to any point in the United States, and allowed U.S. carriers to fly to any point in the Netherlands, a country about the size of West Virginia. The U.S. was ideologically wedded to open markets, so the imbalance in traffic rights was of no concern. Moreover, opening up the Netherlands would allow KLM to drain traffic from surrounding airline networks, which would eventually encourage the surrounding airlines to ask their governments to sign “open skies” bilateral with the United States. • 1993 - the U.S. conferred antitrust immunity on the Wings Alliance between Northwest Airlines and KLM. The encirclement policy began to corrode resistance to liberalization as the sixth freedom traffic drain began to grow; soon Lufthansa, then Air France, were asking their governments to sign liberal bilaterals. • 1996 - Germany fell, followed by the Czech Republic, Italy, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Malta, Poland. • 2001- the United States had concluded bilateral open skies agreements with 52 nations and concluded its first multilateral open skies agreement with Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore. • 2002 – France fell. • 2007 - The U.S. and E.U. concluded a multilateral “open skies” traffic agreement that liberalized everything but foreign ownership and cabotage. • 2011 – cumulatively, the U.S. had signed “open skies” bilaterals with more than100 States. Multilateral and Bilateral Air Transport Agreements • Section 5 of the Transit Agreement, and Section 6 of the Transport Agreement, provide: “Each contracting State reserves the right to withhold or revoke a certificate or permit to an air transport enterprise of another State in any case where it is not satisfied that substantial ownership and effective control are vested in nationals of a contracting State . -

Sky Pearl Club Membership Guide

SKY PEARL CLUB MEMBERSHIP GUIDE Welcome to China Southern Airlines’ Sky Pearl Club The Sky Pearl Club is the frequent flyer program of China Southern Airlines. From the moment you join The Sky Pearl Club, you will experience a whole new world of exciting new travel opportunities with China Southern! Whether you’re traveling for business or pleasure, you’ll be earning mileage toward your award goals every time you fly. Many Elite tier services have been prepared for you. We trust this Guide will soon help you reach your award flight to your dream destinations. China Southern Sky Pearl Club cares about you! 1 A B Earning CZ mileage Redeeming CZ mileage Airlines China Southern Airlines Award Ticket Hotels China Southern Airlines Award Upgrade Banks Partner Airlines Award Ticket Telecommunications, Car Rentals, Business Travel,Dining and others C D Enjoying Sky Pearl Elite Benefits Getting Acquainted with Sky Pearl Rules Definition Membership tiers Membership Qualification and Mileage Account Elite Qualification Mileage Accrual Elite Benefits Mileage Redemption Little Pearl Benefits Membership tier and Elite benefits 2 Others A Earning CZ mileage Whether it’s in the air or on the ground, The Sky Pearl Club gives you more opportunities than ever before to earn Award travel. When flying with China Southern or one of our many airline partners, you can earn FFP mileage. But, that’s not the only way! Hotels stays, car rentals, credit card services, telecommunication services or dining with our business-to-business partners can also help you earn mileage. 3 Airlines Upon making your reservation and ticket booking, please provide your Sky Pearl Club membership number and make sure that passenger’s name and ID is the same as that of your mileage account.