Arxiv:1508.07294V2 [Astro-Ph.HE] 28 Sep 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubble Revisits the Veil Nebula 2 April 2021

Image: Hubble revisits the Veil Nebula 2 April 2021 this stellar violence, the shockwaves and debris from the supernova sculpted the Veil Nebula's delicate tracery of ionized gas—creating a scene of surprising astronomical beauty. The Veil Nebula is also featured in Hubble's Caldwell Catalog, a collection of astronomical objects that have been imaged by Hubble and are visible to amateur astronomers in the night sky. Provided by NASA Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, Z. Levay This image taken by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope revisits the Veil Nebula, which was featured in a previous Hubble image release. In this image, new processing techniques have been applied, bringing out fine details of the nebula's delicate threads and filaments of ionized gas. To create this colorful image, observations were taken by Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 instrument using five different filters. The new post-processing methods have further enhanced details of emissions from doubly ionized oxygen (seen here in blues), ionized hydrogen, and ionized nitrogen (seen here in reds). The Veil Nebula lies around 2,100 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Cygnus (the Swan), making it a relatively close neighbor in astronomical terms. Only a small portion of the nebula was captured in this image. The Veil Nebula is the visible portion of the nearby Cygnus Loop, a supernova remnant formed roughly 10,000 years ago by the death of a massive star. That star—which was 20 times the mass of the Sun—lived fast and died young, ending its life in a cataclysmic release of energy. -

Binocular Challenge Here

AHSP Binocular Observing Award Compiled by Phil Harrington www.philharrington.net • To qualify for the BOA pin, you must see 15 of the following 20 binocular targets. Check off each as you spot them. Seen # Object Const. Type* RA Dec Mag Size Nickname 1. M13 Her GC 16 41.7 +36 28 5.9 16' Great Hercules Globular 2. M57 Lyr PN 18 53.6 +33 02 9.7 86"x62" Ring Nebula 3. Collinder 399 Vul AS 19 25.4 +20 11 3.6 60' Coathanger/Brocchi’s Cluster 3.1 4. Albireo Cyg Dbl 19 30.7 +27 57 35” Color Contrasting Double 5.1 5. M27 Vul PN 19 59.6 +22 43 8.1 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 6. NGC 6992 Cyg SNR 20 56.4 +31 43 - 60'x8 Veil Nebula (east) 7. NGC 7000 Cyg BN 20 58.8 +44 20 - 120'x100' North America Nebula 8. M15 Peg GC 21 30.0 +12 10 7.5 12’ Great Pegasus Cluster 9. M39 Cyg OC 21 32.2 +48 26 4.6 32' 10. Barnard 168 Cyg DN 21 53.2 +47 12 - 100'x10' West of Cocoon Nebula 11. IC 5146 Cyg BN/OC 21 53.5 +47 16 - 12'x12' Cocoon Nebula 12. M110 And Gx 00 40.4 +41 41 10 17’x10’ 13. M32 And Gx 00 42.8 +40 52 10 8’x6’ 14. M31 And Gx 00 42.8 +41 16 4.5 178’ Andromeda Galaxy 15. NGC 457 Cas OC 01 19.1 +58 20 6.4 13’ Owl Cluster/ET Cluster 16. -

Observatories Combine to Crack Open the Crab Nebula 10 May 2017, by Ray Villard

Observatories combine to crack open the Crab Nebula 10 May 2017, by Ray Villard The Crab Nebula, the result of a bright supernova explosion seen by Chinese and other astronomers in the year 1054, is 6,500 light-years from Earth. At its center is a super-dense neutron star, rotating once every 33 milliseconds, shooting out rotating lighthouse-like beams of radio waves and light—a pulsar (the bright dot at image center). The nebula's intricate shape is caused by a complex interplay of the pulsar, a fast-moving wind of particles coming from the pulsar, and material originally ejected by the supernova explosion and by the star itself before the explosion. This image combines data from five different telescopes: The VLA (radio) in red; Spitzer Space Telescope (infrared) in yellow; Hubble Space Telescope (visible) in green; XMM-Newton (ultraviolet) in blue; and Chandra X-ray Observatory (X-ray) in purple. The new VLA, Hubble, and Chandra observations An image of the Crab Nebula, a supernova remnant that all were made at nearly the same time in November was assembled by combining data from five telescopes of 2012. A team of scientists led by Gloria Dubner spanning nearly the entire breadth of the of the Institute of Astronomy and Physics (IAFE), electromagnetic spectrum: the Very Large Array, the the National Council of Scientific Research Spitzer Space Telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope, (CONICET), and the University of Buenos Aires in the XMM-Newton Observatory, and the Chandra X-ray Argentina then made a thorough analysis of the Observatory. Credit: NASA, ESA, NRAO/AUI/NSF and G. -

GMRT Observing Application

GMRT Observing Application CYCLE 15 DEADLINE: Monday, July 07, 2008 Proposal Code: INSTRUCTIONS: Each numbered item must have an entry or N/A or NA SEND TO: GMRT Time Allocation Committee, NCRA–TIFR, Post Bag 3, Ganeshkhind, Pune 411 007, INDIA Received: Email: [email protected] (1) Date of preparing this application: July 6, 2008 (2) Title of Proposal: The first low radio frequencies study of the intriguing SNR G347.3−0.5 (RX J1713.7−3946) (3) AUTHORS† INSTITUT ION Will come Email (needed for PI & Co-PIs) Nationality * to GMRT? FABIO ACERO CEA Saclay, France Yes [email protected] French Mamta Pandey-Pommier Univeristy of Leiden No [email protected] Indian Martin Ortega IAFE, Argentina No [email protected] Argentine Gloria Dubner IAFE, Argentina No [email protected] Argentine Gabriela Castelletti IAFE, Argentina No [email protected] Argentine Elsa Giacani IAFE, Argentina No [email protected] Argentine Alexandre Marcowith Universit´eMontpellier II No [email protected] French Yves Gallant Universit´eMontpellier II No [email protected] Canadian Armand Fiasson Universit´eMontpellier II No armand.fi[email protected] French Jean Ballet CEA Saclay, France No [email protected] French Anne Decourchelle CEA Saclay, France No [email protected] French † Please write the PI’s name in CAPITAL LETTERS. * Nationality is mandatory to obtain official clearance, only for non-Indian nationals coming for observations. (4) Related previous GMRT proposal number(s): None (5) Contact author Address: M. Pandey-Pommier, Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Oort Gebouw, P.O. -

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection an Addition To: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection An addition to: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag. PSA Observation Notes: Chart RA Dec Chart 1) Date Time 2 Equipment) 3) Notes # Observing Notes # Sgr M24 The Sagittarias Star Cloud 1. Mag 4.60 RA 18:16.5 Dec -18:50 Distance: 10.0 2. (kly)Star cloud, 95’ x 35’, Small Sagittarius star cloud 3. lies a little over 7 degrees north of teapot lid. Look for 7,8 dark Lanes! Wealth of stars. M24 has dark nebula 67 (interstellar dust – often visible in the infrared (cooler radiation)). Barnard 92 – near the edge northwest – oval in shape. Ref: Celestial Sampler Floating on Cloud 24, p.112 Sgr M18 - 1. RA 18 19.9, Dec -17.08 Distance: 4.9 (kly) 2. Lies less than 1deg above the northern edge of M24. 3 8 Often bypassed by showy neighbours, it is visible as a 67 small hazy patch. Note it's much closer (1/2 the distance) as compared to M24 (10kly) Sgr M17 (Swan Nebula) and M16 – HII region 1. Nebula and Open Clusters 2. 8 67 M17 Wikipedia 3. Ref: Celestial Sampler p. 113 Sct M11 Wild Duck Cluster 5.80 1. 18:51.1 -06:16 Distance: 6.0 (kly) 2. Open cluster, 13’, You can find the “wild duck” cluster, 3. as Admiral Smyth called it, nearly three degrees west of 67 8 Aquila’s beak lying in one of the densest parts of the summer Milky Way: the Scutum Star Cloud. 9 64 10 Vul M27 Dumbbell Nebula 1. -

Binocular Star Gazing at RCDO 8-22-2015

The Ephemeris September 2015 Volume 26 Number 03 - The Official Publication of the San Jose Astronomical Association SJAA Tour and Fund Raiser for Lick Observatory As many of you know, our local Lick Observatory atop Mt. Hamilton, was threatened with termination of funding by the University of California Regents. Despite UC’s decision to reverse itself and reinstate it’s funding, Lick still fac- es major financial challenges. SJAA Director, Bill O’Neil, volunteered to or- ganize a private SJAA Tour of Lick Observatory with the purpose of raising awareness and Funds for Lick. Sept - Nov 2015 Events 34 generous SJAA members and their guests travelled up the winding Mt. Hamilton Road on May 27, 2015 and paid $50 per person to raise $1,700 for Board & General Meetings Saturday 9/26, 10/24, 11/21 Lick. In the last SJAA Ephemeris, there was an article about the recent Board Meetings: 6 -7:30pm Google Star Party during which Google announced they were granting Lick General Meetings: 7:30-9:30pm Observatory $500K per year for the next two years, with the hopes of generat- ing matching funds from private donors and other silicon valley companies. Solar Observing (locations differ) 9/19, 10/11, 11/1, Our host for the evening was Dr. Ellie Gates, one of Lick’s resident astrono- mers, assisted by public program telescope operator Bob Havner. Our Tour Fix-It Day (2-4pm) included: a presentation in the Lecture Hall about the history of James Lick Sunday 9/6, 10/4, 11/1 Observatory (first opened in 1888); a tour of the facility, including seeing the -

Pos(MQW7)105 Cygni Γ Radio flaring Ce

The compact radio counterpart of IGR J20187+4041 near the flaring source AGL 2021+4029 and 3EG J2020+4017 Zsolt Paragi PoS(MQW7)105 JIVE, Dwingeloo, Netherlands MTA Research Group for Physical Geodesy and Geodynamics, Penc, Hungary E-mail: [email protected] Alfonso Trejo Cruz CRyA-UNAM, Morelia, Mexico E-mail: [email protected] Elsa Giacani IAFE, Buenos Aires, Argentina E-mail: [email protected] Gloria Dubner IAFE, Buenos Aires, Argentina E-mail: [email protected] Andrei M. Bykov Ioffe Institute, St. Petersburg, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Huib J. van Langevelde JIVE, Dwingeloo, Netherlands Sterrewacht Leiden, Leiden University, Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] We present radio results from short e-EVN (EuropeanVLBI network) observations of the counter- part to IGR J20187+4041, a hard X-ray source projected against the γ Cygni supernova remnant (SNR). The brightest unidentified EGRET source 3EG J2020+4017 is also located in the γ Cygni region, though its relation to IGR J20187+4041 has not been well established yet. The e-EVN observations were carried out following the AGILE detection of gamma-ray flaring activity in the region. Our observations show that the radio counterpart to the IGR source has a compact structure on the ∼10 mas scales that could be related to a compact object, but no radio flaring activity has been observed. e-VLBI∗is a technique which makes it possible to image the structure of radio sources at the highest angular resolution on a very short timescale. VII Microquasar Workshop: Microquasars and Beyond September 1-5 2008 Foca, Izmir, Turkey ∗e-VLBI developments in Europe are supported by the EC DG-INFSO funded Communication Network De- c Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Licence. -

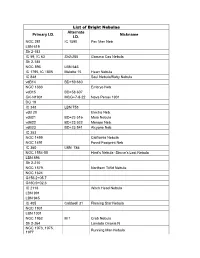

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky

Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky The heavens proclaim the glory of God. The skies display his craftsmanship. Psalm 19:1 NLT Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky Light Year Calculation: Simple! [Speed] 300 000 km/s [Time] x 60 s x 60 m x 24 h x 365.25 d [Distance] ≈ 10 000 000 000 000 km ≈ 63 000 AU Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky Milkyway Galaxy Hyades Star Cluster = 151 ly Barnard 68 Nebula = 400 ly Pleiades Star Cluster = 444 ly Coalsack Nebula = 600 ly Betelgeuse Star = 643 ly Helix Nebula = 700 ly Helix Nebula = 700 ly Witch Head Nebula = 900 ly Spirograph Nebula = 1 100 ly Orion Nebula = 1 344 ly Dumbbell Nebula = 1 360 ly Dumbbell Nebula = 1 360 ly Flame Nebula = 1 400 ly Flame Nebula = 1 400 ly Veil Nebula = 1 470 ly Horsehead Nebula = 1 500 ly Horsehead Nebula = 1 500 ly Sh2-106 Nebula = 2 000 ly Twin Jet Nebula = 2 100 ly Ring Nebula = 2 300 ly Ring Nebula = 2 300 ly NGC 2264 Nebula = 2 700 ly Cone Nebula = 2 700 ly Eskimo Nebula = 2 870 ly Sh2-71 Nebula = 3 200 ly Cat’s Eye Nebula = 3 300 ly Cat’s Eye Nebula = 3 300 ly IRAS 23166+1655 Nebula = 3 400 ly IRAS 23166+1655 Nebula = 3 400 ly Butterfly Nebula = 3 800 ly Lagoon Nebula = 4 100 ly Rotten Egg Nebula = 4 200 ly Trifid Nebula = 5 200 ly Monkey Head Nebula = 5 200 ly Lobster Nebula = 5 500 ly Pismis 24 Star Cluster = 5 500 ly Omega Nebula = 6 000 ly Crab Nebula = 6 500 ly RS Puppis Variable Star = 6 500 ly Eagle Nebula = 7 000 ly Eagle Nebula ‘Pillars of Creation’ = 7 000 ly SN1006 Supernova = 7 200 ly Red Spider Nebula = 8 000 ly Engraved Hourglass Nebula -

Binocular Observing Olympics Stellafane 2018

Binocular Observing Olympics Stellafane 2018 Compiled by Phil Harrington www.philharrington.net • To qualify for the BOO pin, you must see 15 of the following 20 binocular targets. Check off each as you spot them. Seen # Object Const. Type* RA Dec Mag Size Nickname 1. M4 Sco GC 16 23.6 -26 32 6.0 26' Cat’s Eye Globular 2. M13 Her GC 16 41.7 +36 28 5.9 16' Great Hercules Globular 3. M6 Sco OC 17 40.1 -32 13 4.2 15' Butterfly Cluster 4. IC 4665 Oph OC 17 46.3 +05 43 4.2 41' Summer Beehive 5. M7 Sco OC 17 53.9 -34 49 3.3 80' Ptolemy’s Cluster 6. M20 Sgr BN/OC 18 02.6 -23 02 8.5 29'x27' Trifid Nebula 7. M8 Sgr BN/OC 18 03.8 -24 23 5.8 90'x40' Lagoon Nebula 8. M17 Sgr BN 18 20.8 -16 11 7 46'x37' Swan or Omega Nebula 9. M22 Sgr GC 18 36.4 -23 54 5.1 24' Great Sagittarius Cluster 10. M11 Sct OC 18 51.1 -06 16 5.8 14' Wild Duck Cluster 11. M57 Lyr PN 18 53.6 +33 02 9.7 70"x150" Ring Nebula 12. Collinder 399 Vul AS 19 25.4 +20 11 3.6 60' Coathanger/Brocchi’s Cluster 13. PK 64+5.1 Cyg PN 19 34.8 +30 31 9.6p 8" Campbell's Hydrogen Star 14. M27 Vul PN 19 59.6 +22 43 8.1 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 15. -

Supernovae and Supernova Remnants

Supernovae and supernova remnants Mikako Matsuura (Cardiff University) Why are SNe & SNRs important? Path to the first dust in the Universe • Synthase heavy elements Condensation to dust O • dust formation Fe Si • Source of kinetic energy into the ISM C • dust destruction Injection of elements Supernovae – death of massive stars Formation of the first generation of stars Big Bang Why are SNe & SNRs important? • Synthase heavy elements • dust formation • Source of kinetic energy into the ISM • dust destruction Supernova remnant NGC 6960 (Veil Nebula) 100-1000 km s-1 Shocks M82 Galactic outflow Key questions • Are supernovae & supernova remnants dust producer or destroyer? • If dust producer: • What is the net dust mass? • What types of dust grains are formed? • If destroyer: • How efficient? • How does affect grain size distributions? It is getting clear that SNe form substantial mass of dust using newly synthesized elements Cassiopeia A (AD 1681?) Crab Nebula (AD 1054 ) Supernova 1987A SNe in nearby galaxies 0.1-0.5 M¤ 0.03-0.05 M¤ ~0.5 M¤ 0.0001–0.02 M¤? IR dust observations: only ~10 SNe + SNRs e.g. Sugerman et al. (2006), Matsuura et al. (2015), De Looze et al. (2017; 2019) Target opportunity – extra-galactic SNe SN 2014J 2MASS pre-explosion SOFIA/FLITECAM SOFIA observations of SN 2014J in M82 – unfortunately no dust Template for extragalactic SNe – Time evolution of SN 1987A SOFIA SN 1987A (50kpc) • The peak of SED shifted to longer wavelength in tiMe • The inferred mass increases in tiMe? • 0.001 M¤ at day 615 Harvey et al. (1989), Wooden et al. -

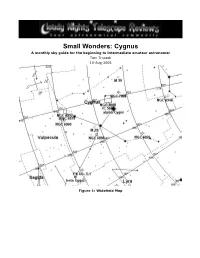

Cygnus a Monthly Sky Guide for the Beginning to Intermediate Amateur Astronomer Tom Trusock 10-Aug-2005

Small Wonders: Cygnus A monthly sky guide for the beginning to intermediate amateur astronomer Tom Trusock 10-Aug-2005 Figure 1: Widefield Map 2/16 Small Wonders: Cygnus Target List Object Type Size Mag RA Dec α (alpha) Cygni (Deneb) Star 1.3 20h 41m 38.7s 45 17' 59" β (beta) Cygni (Albireo) Star 3 19h 30m 57.9s 27 58' 18" NGC 7000 Bright Nebula 120.0'x100.0' 4 20h 59m 03.2s 44 32' 16" IC 5070 Bright Nebula 60.0'x50.0' 8 20h 51m 01.1s 44 12' 13" NGC 6960 Supernova Remnant 70.0'x6.0' 7 20h 45m 57.0s 30 44' 12" NGC 6979 Bright Nebula 7.0'x3.0' 20h 51m 14.9s 32 10' 14" NGC 6992 Bright Nebula 60.0'x8.0' 7 20h 56m 39.0s 31 44' 16" M 29 Open Cluster 10.0' 6.6 20h 24m 11.6s 38 30' 58" M 39 Open Cluster 31.0' 4.6 21h 32m 10.4s 48 26' 40" NGC 6826 Planetary Nebula 36" 8.8 19h 44m 58.8s 50 32' 21" NGC 7026 Planetary Nebula 45" 10.9 21h 06m 31.4s 47 52' 28" NGC 6888 Bright Nebula 18.0'x13.0' 10 20h 12m 20.0s 38 22' 18" NGC 6946 Galaxy 11.5'x9.8' 9 20h 35m 01.0s 60 10' 19" Challenge Objects Object Type Size Mag RA Dec PK 64+ 5.1 Planetary Nebula 5" 9.6 19h 35m 02.3s 30 31' 45" Sh2-112 9.0'x7.0' Cygnus ygnus is a spectacular summer constellation.