Decentralization in Ethiopia – Who Benefits?*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Governing the Ungovernable: Contesting and Reworking REDD+ in Indonesia

Governing the ungovernable: contesting and reworking REDD+ in Indonesia Abidah B. Setyowati1 Australian National University, Australia Abstract Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation plus the role of conservation, sustainable forest management, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries (REDD+) has rapidly become a dominant approach in mitigating climate change. Building on the Foucauldian governmentality literature and drawing on a case study of Ulu Masen Project in Aceh, Indonesia, this article examines the practices of subject making through which REDD+ seeks to enroll local actors, a research area that remains relatively underexplored. It interrogates the ways in which local actors react, resist or maneuver within these efforts, as they negotiate multiple subject positions. Interviews and focus group discussions combined with an analysis of documents show that the subject making processes proceed at a complex conjuncture constituted and shaped by political, economic and ecological conditions within the context of Aceh. The findings also suggest that the agency of communities in engaging, negotiating and even contesting the REDD+ initiative is closely linked to the history of their prior engagement in conservation and development initiatives. Communities are empowered by their participation in REDD+, although not always in the ways expected by project implementers and conservation and development actors. Furthermore, communities' political agency cannot be understood by simply examining their resistance toward the initiative; these communities have also been skillful in playing multiple roles and negotiating different subjectivities depending on the situations they encounter. Keywords: REDD+, subject-making, agency, resistance, Indonesia, Aceh Résumé La réduction des émissions dues à la déforestation et à la dégradation des forêts (REDD +) est rapidement devenue une approche dominante pour atténuer le changement climatique. -

Belait District

BELAIT DISTRICT His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah ibni Al-Marhum Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien Sultan and Yang Di-Pertuan of Brunei Darussalam ..................................................................................... Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Paduka Seri Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah ibni Al-Marhum Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien Sultan dan Yang Di-Pertuan Negara Brunei Darussalam BELAIT DISTRICT Published by English News Division Information Department Prime Minister’s Office Brunei Darussalam BB3510 The contents, generally, are based on information available in Brunei Darussalam Newsletter and Brunei Today First Edition 1988 Second Edition 2011 Editoriol Advisory Board/Sidang Redaksi Dr. Haji Muhammad Hadi bin Muhammad Melayong (hadi.melayong@ information.gov.bn) Hajah Noorashidah binti Haji Aliomar ([email protected]) Editor/Penyunting Sastra Sarini Haji Julaini ([email protected]) Sub Editor/Penolong Penyunting Hajah Noorhijrah Haji Idris (noorhijrah.idris @information.gov.bn) Text & Translation/Teks & Terjemahan Hajah Apsah Haji Sahdan ([email protected]) Layout/Reka Letak Hajah Apsah Haji Sahdan Proof reader/Penyemak Hajah Norpisah Md. Salleh ([email protected]) Map of Brunei/Peta Brunei Haji Roslan bin Haji Md. Daud ([email protected]) Photos/Foto Photography & Audio Visual Division of Information Department / Bahagian Fotografi -

Kamu Terim Bankası

TÜRKÇE-İNGİLİZCE Kamu Terim Ban•ka•sı Kamu kurumlarının istifadesine yönelik Türkçe-İngilizce Terim Bankası Term Bank for Public Institutions in Turkey Term Bank for use by public institutions in Turkish and English ktb.iletisim.gov.tr Kamu Terim Ban•ka•sı Kamu kurumlarının istifadesine yönelik Türkçe-İngilizce Terim Bankası Term Bank for Public Institutions in Turkey Term Bank for use by public institutions in Turkish and English © İLETİŞİM BAŞKANLIĞI • 2021 ISBN: 978-625-7779-95-1 Kamu Terim Bankası © 2021 CUMHURBAŞKANLIĞI İLETİŞİM BAŞKANLIĞI YAYINLARI Yayıncı Sertifika No: 45482 1. Baskı, İstanbul, 2021 İletişim Kızılırmak Mahallesi Mevlana Bulv. No:144 Çukurambar Ankara/TÜRKİYE T +90 312 590 20 00 | [email protected] Baskı Prestij Grafik Rek. ve Mat. San. ve Tic. Ltd. Şti. T 0 212 489 40 63, İstanbul Matbaa Sertifika No: 45590 Takdim Türkiye’nin uluslararası sahada etkili ve nitelikli temsili, 2023 hedeflerine kararlılıkla yürüyen ülkemiz için hayati öneme sahiptir. Türkiye, Sayın Cumhurbaşkanımız Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’ın liderliğinde ortaya koyduğu insani, ahlaki, vicdani tutum ve politikalar ile her daim barıştan yana olduğunu tüm dünyaya göstermiştir. Bölgesinde istikrar ve barışın sürekliliğinin sağlanması için büyük çaba sarf eden Türkiye’nin haklı davasının kamuoylarına doğru ve tutarlı bir şekilde anlatılması gerekmektedir. Bu çerçevede kamu kurumları başta olmak üzere tüm sektörlerde çeviri söylem birliğini sağlamak ve ifadelerin yerinde kullanılmasını temin etmek büyük önem arz etmektedir. İletişim Başkanlığı, Devletimizin tüm kurumlarını kapsayacak ortak bir dil anlayışını merkeze alan, ulusal ve uluslararası düzeyde bütünlüklü bir iletişim stratejisi oluşturmayı kendisine misyon edinmiştir. Bu doğrultuda Başkanlığımız kamu sektöründe yürütülen çeviri faaliyetlerinde ortak bir dil oluşturmak, söylem birliğini sağlamak ve çeviri süreçlerini hızlandırmak amacıyla çeşitli çalışmalar yapmaktadır. -

Friday Morning, 6 December 2013 Union Square 23/24, 9:00 A.M

FRIDAY MORNING, 6 DECEMBER 2013 UNION SQUARE 23/24, 9:00 A.M. TO 10:45 A.M. Session 5aAB Animal Bioacoustics: Animal Hearing and Vocalization Michael A. Stocker, Chair Ocean Conservation Research, P.O. Box 559, Lagunitas, CA 94938 Contributed Papers 9:00 9:30 5aAB1. A comparison of acoustic and visual metrics of sperm whale 5aAB3. Psychophysical studies of hearing in sea otters (Enhydra lutris). longline depredation. Aaron Thode (SIO, UCSD, 9500 Gilman Dr., MC Asila Ghoul and Colleen Reichmuth (Inst. of Marine Sci., Long Marine 0238, La Jolla, CA 92093-0238, [email protected]), Lauren Wild (Sitka Lab., Univ. of California Santa Cruz, 100 Shaffer Rd., Santa Cruz, CA Sound Sci. Ctr., Sitka, AK), Delphine Mathias (GIPSA Lab., Grenoble INP, 95060, [email protected]) St. Martin d’He`res, France), Janice Straley (Univ. of Alaska Southeast, The sensory biology of sea otters is of special interest, given their am- Sitka, AK), and Chris Lunsford (Auke Bay Labs., NOAA, Juneau, AK) phibious nature and their recent evolutionary transition from land to sea. Annual federal stock assessment surveys for Alaskan sablefish also However, little is known about the acoustic sense of sea otters, including attempt to measure sperm whale depredation by quantifying visual evidence sensitivity to airborne and underwater sound. In this study, we sought to of depredation, including lip remains and damaged fish. An alternate passive obtain direct measures of auditory function. We trained an adult-male south- acoustic method for quantifying depredation was investigated during the ern sea otter to participate in audiometric testing in an acoustic chamber and 2011 and 2012 survey hauls. -

Mukim Concept As Government Administrators in Acehω

202 MUKIM CONCEPT AS GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATORS IN ACEHΩ Mukhlis Law Faculty of Malikussaleh University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Mukim as administrators of Governance in Aceh was set by law and the qanun-qanun in Aceh, however be a resident of the organizing functions of governance have not been described in detail. This paper outlines the concept of Mukim as administrators in Aceh.The method used in this research is the study of normative law with specifications descriptive analytical study using normative juridical approach. Article 114 of Law No. 11 of 2006 shall be clearly stated that the governance is composed of government mukim and tuha peut or another name. Related functions, completeness/device,the process of selecting/filling positions and institutions in mukim level set in qanun district/city and urban areas or district/city capital does not have to be formed mukim . Key words: mukim, qanun, gampong Abstrak Mukim sebagai penyelenggara pemerintahan di Aceh sudah diatur dalam undang-undang dan qanun- qanun di Aceh, namun fungsi mukim dalam menyelenggarakan pemerintahan belum dijelaskan secara terperinci. Tulisan ini menguraikan konsep mukim sebagai penyelenggara pemerintahan di Aceh. Metode penelitian yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini adalah penelitian hukum normatif dengan spesifikasi penelitian deskriptif analitis yang menggunakan pendekatan yuridis normatif. Pasal 114 UU No. 11 Tahun 2006 perlu disebutkan dengan jelas bahwa Pemerintahan mukim terdiri dari pemerin- tah mukim dan tuha peut mukim atau nama lain. Terkait dengan fungsi, kelengkapan/perangkat, proses pemilihan/pengisian jabatan dan lembaga-lembaga di tingkat mukim diatur dalam qanun kabupaten/kota serta untuk daerah perkotaan atau ibukota kabupaten/kota tidak harus dibentuk mukim. -

Gubernur Aceh Nomor 92 Tahun 2019430/06/2009

PERATURAN GUBERNUR ACEH NOMOR 92 TAHUN 2019430/06/2009 TENTANG PEDOMAN UMUM PENATAAN MUKIM DI ACEH DENGAN RAHMAT ALLAH YANG MAHA KUASA GUBERNUR ACEH, Menimbang : a. bahwa Mukim sebagai salah satu bentuk pemerintahan di Aceh diakui keberadaannya dalam Undang-Undang Nomor 44 Tahun 1999 tentang Penyelenggaraan Keistimewaan Propinsi Daerah Istimewa Aceh dan Undang-Undang Nomor 11 Tahun 2006 tentang Pemerintahan Aceh; b. bahwa dalam rangka efektivitas penataan mukim sebagai bagian kekhususan dan keistimewaan Aceh, perlu pedoman umum penataan Mukim di Aceh; c. bahwa berdasarkan ketentuan Pasal 43 ayat (1) Undang-Undang Nomor 11 Tahun 2006 tentang Pemerintahan Aceh Gubernur dalam kedudukannya sebagai wakil pemerintah memiliki tugas dan wewenang mengkoordinasikan pembinaan dan pengawasan penyelenggaraan pemerintahan Kabupaten/Kota dan pembinaan penyelenggaraan kekhususan dan keistimewaan Aceh; d. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam huruf a, huruf b, dan huruf c, perlu menetapkan Peraturan Gubernur tentang Pedoman Umum Penataan Mukim di Aceh; Mengingat : 1. Undang-Undang Nomor 24 Tahun 1956 tentang Pembentukan Daerah Otonom Propinsi Atjeh dan Perubahan Pembentukan Propinsi Sumatera Utara (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1956 Nomor 64, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 1103); 2. Undang-Undang Nomor 44 Tahun 1999 tentang Penyelenggaraan Keistimewaan Propinsi Daerah Istimewa Aceh (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1999 Nomor 172 Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 3893); 3. Undang-Undang Nomor 11 Tahun 2006 tentang Pemerintahan Aceh (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2006 Nomor 62, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 4633); 4. Peraturan Pemerintah Nomor 12 Tahun 2017 tentang Pembinaan dan Pengawasan Penyelenggaraan Pemerintahan Daerah (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2017 Nomor 73, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 6041); 5. -

Buku Poskod Edisi Ke 2 (Kemaskini 26122018).Pdf

Berikut adalah contoh menulis alamat pada bahgian hadapan sampul surat:- RAJAH PERTAMA PENGGUNAAN MUKA HADAPAN SAMPUL SURAT 74 MM 40 MM Ruangan untuk kegunaan pengirim Ruangan untuk alamat penerima Ruangan 20 MM untuk kegunaan Pejabat Pos 20 MM 140 MM Lebar Panjang Ukuran minimum 90 mm 140 mm Ukuran maksimum 144 mm 264 mm Bagi surat yang dikirim melalui pos, alamat pengirim hendaklah ditulis pada bahagian penutup belakang sampul surat. Ini membolehkan surat berkenaan dapat dikembalikan kepada pengirim sekiranya surat tersebut tidak dapat diserahkan kepada si penerima seperti yang dikehendaki. Disamping itu. ianya juga menolong penerima mengenal pasti alamat dan poskod awda yang betul. Dengan cara ini penerima akan dapat membalas surat awda dengan alamat dan poskod yang betul. Berikut adalah contoh menulis alamat pengirim pada bahagian penutup sampul surat:- RAJAH DUA Jabatan Perkhidmatan Pos berhasrat memberi perkhidmatan yang efesien kepada awda. Oleh itu, kerjasama awda sangat-sangat diperlukan. Adalah menjadi tugas awda mempastikan ketepatan maklumat-maklumat alamat dan poskod awda kerana ianya merupakan kunci bagi kecepatan penyerahan surat awda GARIS PANDU SKIM POSKOD NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM Y Z 0 0 0 0 Kod Daerah Kod Mukim Kod Kampong / Kod Pejabat Kawasan Penyerahan Contoh: Y Menunjukan Kod Daerah Z Menunjukan Kod Mukim 00 Menunjukan Kod Kampong/Kawasan 00 Menunjukan Kod Pejabat Penyerahan KOD DAERAH BIL Daerah KOD 1. Daerah Brunei Muara B 2. Daerah Belait K 3. Daerah Tutong T 4. Daerah Temburong P POSKOD BAGI KEMENTERIAN- KEMENTERIAN -

Penghulus and Ketua Kampongs: Relevancy and Challenges In

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 191 Asian Association for Public Administration Annual Conference (AAPA 2018) Penghulus and Ketua Kampongs: Relevancy and Challenges in Brunei Darussalam Sub-Theme: Strengthening Local Administration and Decentralisation Li Li Pang1 Universiti Brunei Darussalam 1 [email protected] Abstract The institutions of Penghulu (head of sub-district or Mukim) and Ketua Kampong (head of a village) are an important part of Brunei Darussalam’s administrative structure, officially seen as the ‘eyes, ears and mouth’ of the government. However, due to the advancement of information communication technologies (ICTs) as well as the rise of a large bureaucratic state, are these institutions still relevant in this small absolute monarchy? What are the challenges faced by the Penghulus and Ketua Kampongs in this modern age and what do the youth think of them? Is it still necessary for the government to increase the financial benefits of Penghulus and Ketua Kampongs in order to attract younger, educated generation to fill up vacancies for those positions? This paper attempts to provide a preliminary investigation on these under-research issues in Brunei Darussalam as well as providing an insight into the local administration of a small rentier state in Southeast Asia. Introduction The institutions of Penghulu and Ketua Kampongs (KKs), as leaders of villages and sub- districts (Mukims) are a common social-administrative feature in the Malay Archipelago and their role in modern governance is under-researched. Formally institutionalised by the British and Dutch colonisers, Penghulus and KKs contributions in Malaysia and Indonesia were significant in the 18th and 19th century as they ensured peaceful administration of the state as the local headmen were allowed to continue leading their respective villages (Cheema, 1979; Kratoska, 1984; Tsuboi, 2004; Wan Rabiah, Kushairi, Suharto and Hasnan, 2015). -

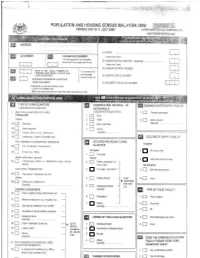

Malaysia 2000 Enumeration Form

.. CENSUS DAY IS 5 JULY 2000 LlYlNG QUARTERS {LQ), HaUSEHCLD (?!di AND PERSON PARTICULARS .............................................. (1) STATE .......................................................................... ( Name and Code ) (2) ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT I JAJAHAN ..................................... ( Name and Code ) (3) CENSUS DISTRICT NUMBER For Household 02 (4) CENSUS CIRCLE NUMBER cancel K3 and K4 DS LIVE IN THIS LIVING QUARTERS? J (5) ENUMERATION BLOCK NUMBER Household is a group ofpersons who : - Usually live together and - Make common provisions for food and other essentials of living TYPE OF LIVING QUARTERS ( OBSERVATION QUESTION) i) BUILT OR CONVERTED FOR LIVING ( OBSERVATION QUESTION) 1 0 Treated Diped water Housinq Unit 1 0 Brick House 2 0 Plank 2 0 Othersources (Spec/&/) O1 Detached 3 0 Brickand Plank O2 Semi-deiached t 03 Terrace. Row or Link, Townhouse -I ELECTRICITY SUPPLY FACILI I Y O4 Longhouse ( Sabah & Sarawak only.) I -- 7 Flat lAparfmentl Condominium / Shophouse OCCUPIED OR VACANT LIVING I QUARTERS I 05 F,,I-t I Apartment I Condominium i Occupied 1 24 hoursaday e5 [7 ~hc;hcuse I office 1 0 Occupied 1 Room (with direct access) Vacant 2 Less than 24 hours a day 07 c] In Shophouse, Office; In I Attached to House. Factory, 2 Newly completed I for Mill etc. rent or sale Not Supplied lmprovised / Temporary Hut 3 For repair I renovation 3 c] Self-owned generator 08 lmprovised I Temporary Hut, etc. Others 4 u Holiday Resort (END 4 0 None INTERVIEW O9 Others ( e.g. mobile unit ) a (Specify) ................................................................. FOR THIS 5 0 Seasonalworkers LQ 1 Collective Living Quarters Quarters TYPE OF TOILET FACILIT'I 10 0 Hotel, Lodging House, Rest House, etc. -

The Role of Mukim in Aceh Development

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 413 1st International Conference on Law, Governance and Islamic Society (ICOLGIS 2019) The Role of Mukim in Aceh Development Muhammad Ikhsan Ahyat1,* Badaruddin1 , Humaizi1, Heri Kusmanto1 1Faculty of Social and Political Science, Universitas Sumatera Utara Medan, Indonesia *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Aceh is one of the well-known province of the Aceh Kingdom, one of the great Islamic Kingdom in the world. Islam creates all cultures in Aceh, including the government system. Mukim is unique, only found in the Aceh government structure, influenced by Islam. This study addressed this research problem: To what extent mukim play his roles in Aceh development. The method employed was social research supported by library research. The result showed that the first function of Mukim was a leader of Friday praying. Because of the charismatic profile and his ability to stand and mediate between Sultan and people, the position of Mukim was very strategic in the development of Aceh. Unfortunately, after the Independence of Indonesia, role and function of Mukim had reduced. Even in new order era, there was not any Mukim left due to the centralistic system. Later, in the reformation era, Mukim reappears in the government. Regulation number 6 of the Year 2014 about Village was established after the government has seriously considered how to increase the development with Acehnese culture. To sum up, Mukim today reclaims his position, but the function is different from the time in the period of Aceh Kingdom. Government must strive to reformulate the function of Mukim as he used to. -

The Future of Work for Smallholder Farmers in Ethiopia

The Future of Work for smallholder farmers in Ethiopia The Future of Work for smallholder farmers in Ethiopia Policy paper by The West Wing Think Tank for the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs Directie Duurzame Economische Ontwikkeling / Directie Sociale Ontwikkeling 1 The West Wing Think Tank (DDE/DSO track 2018/2019) | Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs Track leader Andrew van Olst Editors Anouk de Vries Sebastiaan Olislagers Track members Adinda van de Walle Amerens Jongsma Eva Pander Maat Helena Arntz Isabella van der Gaag Jessica Sakalauskas Kevin van Langen Michael Holla Robin Klabbers Siert van Kemenade 2 The Future of Work for smallholder farmers in Ethiopia EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Future of Work creates various new opportunities, but also many challenges. While technological developments can drastically increase productivity and efficiency, it can also increase inequality if not dealt with correctly. Governments now have the responsibility to act. For this reason, the DDE/DSO- track of the West Wing Think Tank researched possible effects of the Future of Work. As a case study, this policy advice focuses on how the Future of Work will manifest itself in the agricultural sector of Ethiopia. Our central goal: having Ethiopian smallholder farmers benefit in an inclusive way from technological developments related to the Future of Work in the long-run. Existing research concerning the Future of Work is mainly oriented on Western labor markets. As the Ethiopian labor market is vastly different, the Future of Work will also take a different shape. We determined four relevant technological developments in the near future of the Ethiopian agricultural sector, namely mechanization, online platforms, big data, and artificial intelligence (AI). -

2988 Supplement to the London Gazette, 1 June, 1953

2988 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 1 JUNE, 1953 COLONIAL EMPIRE. ALI s/o Keni, Chief Warder, Luzira Central Prison, Uganda. Charles Samuel THORNE, Head Keeper, South Frank Douglas SLOCOMBE, Senior Messenger, Point Lighthouse, Barbados. Office of the Comptroller, Development and Donald 'ABRAMS, Engineer, Georgetown Fire Welfare Organisation, West Indies. Brigade, British Guiana. Suleiman MUSSA, Nurse, Ziwani Police Lines, Alexander Bertfield CLARKE, lately Sergeant Zanzibar Protectorate. Major, British Honduras Police Force. Hussein Zihni MEHMED, Senior Compositor, Printing Department, Cyprus. Kyriacos NICOLAIDES, Mukhtar at Peyia, Cyprus. CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS Dharam Dev MAYOR, Station Master, Kam- OF KNIGHTHOOD. pala, East Africa High Commission. St. James's Palace, S.W.I. Zainal ABIDIN bin Mohamed Lati, Penghulu 1st June, 19.53. of Lenggeng Mukim, Federation of Malaya. Abu BAKAR bin Tahir, Engineman, Marine De- The QUEEN has been graciously pleased, on partment, Federation of Malaya. the occasion of Her Majesty's Coronation, to Krishnaswamy Iyer BALASUBRAMANIAM, Clerk, award the Royal Victorian Medal (Silver) 10 Police Clerical Service, Federation of the undermentioned: — Malaya. Richard Clement ALLENBY. CHOW Fong, Headman of Sikamat New Vil- Percival Frank ASH. lage, Federation of Malaya. George Henry BIGNELL. Louis Victor JOHN, Technical Assistant, Drain- Robert BISSETT. age and Irrigation Department, Selangor, Charles Henry BROWN. Federation of Malaya. Leopold Isaac Noah BROWN. KEOW Chong Ghee, Station Master, Malayan Alfred James COLE. Railway, Federation of Malaya. Thomas FRASER. LIM Swee Hun, Chief Clerk, Penang Library, Edward Victor GREENER. Federation of Malaya. Stanley Edgar HOOKS. MOHAMED bin Awang Noh, Penghulu of Stanley William Lionel Rivers LUCKING. Temerloh District, Federation of Malaya.