Playing-With the World: Toy Story's Aesthetics and Metaphysics of Play Jonathan Hendricks University of South Florida, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature

Brown, Noel. " An Interview with Steve Segal." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. By Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 197–214. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501324949.ch-013>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 03:24 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 97 Chapter 13 A N INTERVIEW WITH STEVE SEGAL N o e l B r o w n Production histories of Toy Story tend to focus on ‘big names’ such as John Lasseter and Pete Docter. In this book, we also want to convey a sense of the animator’s place in the making of the fi lm and their perspective on what hap- pened, along with their professional journey leading up to that point. Steve Segal was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1949. He made his fi rst animated fi lms as a high school student before studying Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he continued to produce award- winning, independent ani- mated shorts. Aft er graduating, Segal opened a traditional animation studio in Richmond, making commercials and educational fi lms for ten years. Aft er completing the cult animated fi lm Futuropolis (1984), which he co- directed with Phil Trumbo, Segal moved to Hollywood and became interested in com- puter animation. -

Speech Sounds Vowels HOPE

This is the Cochlear™ promise to you. As the global leader in hearing solutions, Cochlear is dedicated to bringing the gift of sound to people all over the world. With our hearing solutions, Cochlear has reconnected over 250,000 cochlear implant and Baha® users to their families, friends and communities in more than 100 countries. Along with the industry’s largest investment in research and development, we continue to partner with leading international Speech Sounds:Vowels researchers and hearing professionals, ensuring that we are at the forefront in the science of hearing. A Guide for Parents and Professionals For the person with hearing loss receiving any one of the Cochlear hearing solutions, our commitment is that for the rest of your life in English and Spanish we will be here to support you Hear now. And always Ideas compiled by CASTLE staff, Department of Otolaryngology As your partner in hearing for life, Cochlear believes it is important that you understand University of North Carolina — Chapel Hill not only the benefits, but also the potential risks associated with any cochlear implant. You should talk to your hearing healthcare provider about who is a candidate for cochlear implantation. Before any cochlear implant surgery, it is important to talk to your doctor about CDC guidelines for pre-surgical vaccinations. Cochlear implants are contraindicated for patients with lesions of the auditory nerve, active ear infections or active disease of the middle ear. Cochlear implantation is a surgical procedure, and carries with it the risks typical for surgery. You may lose residual hearing in the implanted ear. -

How the Motion Picture Industry Miscalculates Box Office Receipts

How the motion picture industry miscalculates box office receipts S. Eric Anderson, Loma Linda University Stewart Albertson, Loma Linda University David Shavlik, Loma Linda University INTRODUCTION when movie grosses are adjusted for inflation, the Sound of Music was a more popular movie Box office grosses, once of interest only to than Titanic even though the box office gross movie industry executives, are now widely was over $400 million less. So why is it then publicized and immediately reported by movie that box office grosses are often the only industry tracking companies. The numbers reported, when the numbers have instantaneous tracking and reporting hurts little meaning? The motion picture industry, movies with weak openings, but helps movies aware that inflation helps movies grow bigger, with big openings become even bigger as has little interest in reporting highest grossing people flock to see what all the fuss is about. box office numbers with inflation-adjusted Due to inflation, the highest grossing movies dollars that will show the motion picture tend to be the more recent releases, which the industry is stagnant at best. They are able to motion picture industry is taking full get away with it since most don’t know how advantage of when promoting new movies. to handle those inflation-adjusting As a result, the motion picture industry has calculations. developed “highest grossing “ movie lists from almost every angle imaginable - opening Inflation-adjusted gross calculations are day, opening weekend, opening day non- inaccurate weekend, opening day during the fall, winter and spring, opening day Memorial weekend, Some tracking companies have begun second weekend of release, fewest screens, reporting box office grosses with the less etc. -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W Inte R 2 0 18 – 19

WINTER 2018–19 BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE 100 YEARS OF COLLECTING JAPANESE ART ARTHUR JAFA MASAKO MIKI HANS HOFMANN FRITZ LANG & GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM INGMAR BERGMAN JIŘÍ TRNKA MIA HANSEN-LØVE JIA ZHANGKE JAMES IVORY JAPANESE FILM CLASSICS DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT IN FOCUS: WRITING FOR CINEMA 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 CALENDAR DEC 9/SUN 21/FRI JAN 2:00 A Midsummer Night’s Dream 4:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 Introduction by Jan Pinkava 7:00 Fanny and Alexander BERGMAN P. 15 1/SAT TRNKA P. 12 3/THU 7:00 Full: Home Again—Tapestry 1:00 Making a Performance 1:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. 6 4:30 The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari P. 5 WORKSHOP P. 6 Reimagined Judith Rosenberg on piano 4–7 Five Tables of the Sea P. 4 5:30 The Good Soldier Švejk TRNKA P. 12 LANG & EXPRESSIONISM P. 16 22/SAT Free First Thursday: Galleries Free All Day 7:30 Persona BERGMAN P. 14 7:00 The Price of Everything P. 15 6:00 The Firemen’s Ball P. 29 5/SAT 2/SUN 12/WED 8:00 The Apartment P. 19 6:00 Future Landscapes WORKSHOP P. 6 12:30 Scenes from a 6:00 Arthur Jafa & Stephen Best 23/SUN Marriage BERGMAN P. 14 CONVERSATION P. 6 9/WED 2:00 Boom for Real: The Late Teenage 2:00 Guided Tour: Old Masters P. 6 7:00 Ugetsu JAPANESE CLASSICS P. 20 Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat P. 15 12:15 Exhibition Highlights Tour P. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

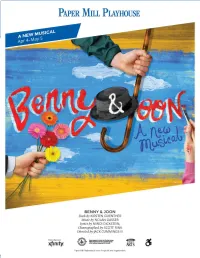

2019-BENNY-AND-JOON.Pdf

CREATIVE TEAM KIRSTEN GUENTHER (Book) is the recipient of a Richard Rodgers Award, Rockefeller Grant, Dramatists Guild Fellowship, and a Lincoln Center Honorarium. Current projects include Universal’s Heart and Souls, Measure of Success (Amanda Lipitz Productions), Mrs. Sharp (Richard Rodgers Award workshop; Playwrights Horizons, starring Jane Krakowski, dir. Michael Greif), and writing a new book to Paramount’s Roman Holiday. She wrote the book and lyrics for Little Miss Fix-it (as seen on NBC), among others. Previously, Kirsten lived in Paris, where she worked as a Paris correspondent (usatoday.com). MFA, NYU Graduate Musical Theatre Writing Program. ASCAP and Dramatists Guild. For my brother, Travis. NOLAN GASSER (Music) is a critically acclaimed composer, pianist, and musicologist—notably, the architect of Pandora Radio’s Music Genome Project. He holds a PhD in Musicology from Stanford University. His original compositions have been performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, among others. Theatrical projects include the musicals Benny & Joon and Start Me Up and the opera The Secret Garden. His book, Why You Like It: The Science and Culture of Musical Taste (Macmillan), will be released on April 30, 2019, followed by his rock/world CD Border Crossing in June 2019. His TEDx Talk, “Empowering Your Musical Taste,” is available on YouTube. MINDI DICKSTEIN (Lyrics) wrote the lyrics for the Broadway musical Little Women (MTI; Ghostlight/Sh-k-boom). Benny & Joon, based on the MGM film, was a NAMT selection (2016) and had its world premiere at The Old Globe (2017). Mindi’s work has been commissioned, produced, and developed widely, including by Disney (Toy Story: The Musical), Second Stage (Snow in August), Playwrights Horizons (Steinberg Commission), ASCAP Workshop, and Lincoln Center (“Hear and Now: Contemporary Lyricists”). -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

MONSTERS INC 3D Press Kit

©2012 Disney/Pixar. All Rights Reserved. CAST Sullivan . JOHN GOODMAN Mike . BILLY CRYSTAL Boo . MARY GIBBS Randall . STEVE BUSCEMI DISNEY Waternoose . JAMES COBURN Presents Celia . JENNIFER TILLY Roz . BOB PETERSON A Yeti . JOHN RATZENBERGER PIXAR ANIMATION STUDIOS Fungus . FRANK OZ Film Needleman & Smitty . DANIEL GERSON Floor Manager . STEVE SUSSKIND Flint . BONNIE HUNT Bile . JEFF PIDGEON George . SAM BLACK Additional Story Material by . .. BOB PETERSON DAVID SILVERMAN JOE RANFT STORY Story Manager . MARCIA GWENDOLYN JONES Directed by . PETE DOCTER Development Story Supervisor . JILL CULTON Co-Directed by . LEE UNKRICH Story Artists DAVID SILVERMAN MAX BRACE JIM CAPOBIANCO Produced by . DARLA K . ANDERSON DAVID FULP ROB GIBBS Executive Producers . JOHN LASSETER JASON KATZ BUD LUCKEY ANDREW STANTON MATTHEW LUHN TED MATHOT Associate Producer . .. KORI RAE KEN MITCHRONEY SANJAY PATEL Original Story by . PETE DOCTER JEFF PIDGEON JOE RANFT JILL CULTON BOB SCOTT DAVID SKELLY JEFF PIDGEON NATHAN STANTON RALPH EGGLESTON Additional Storyboarding Screenplay by . ANDREW STANTON GEEFWEE BOEDOE JOSEPH “ROCKET” EKERS DANIEL GERSON JORGEN KLUBIEN ANGUS MACLANE Music by . RANDY NEWMAN RICKY VEGA NIERVA FLOYD NORMAN Story Supervisor . BOB PETERSON JAN PINKAVA Film Editor . JIM STEWART Additional Screenplay Material by . ROBERT BAIRD Supervising Technical Director . THOMAS PORTER RHETT REESE Production Designers . HARLEY JESSUP JONATHAN ROBERTS BOB PAULEY Story Consultant . WILL CSAKLOS Art Directors . TIA W . KRATTER Script Coordinators . ESTHER PEARL DOMINIQUE LOUIS SHANNON WOOD Supervising Animators . GLENN MCQUEEN Story Coordinator . ESTHER PEARL RICH QUADE Story Production Assistants . ADRIAN OCHOA Lighting Supervisor . JEAN-CLAUDE J . KALACHE SABINE MAGDELENA KOCH Layout Supervisor . EWAN JOHNSON TOMOKO FERGUSON Shading Supervisor . RICK SAYRE Modeling Supervisor . EBEN OSTBY ART Set Dressing Supervisor . -

The Randy Newman Songbook, Vol. 2 by Allen Morrison June 21St, 2011 at 1:31 Pm

Randy Newman: The Randy Newman Songbook, Vol. 2 By Allen Morrison June 21st, 2011 at 1:31 pm Randy Newman The Randy Newman Songbook, Vol. 2 (Nonesuch) Rating: Randy Newman was talking about the relationship between his film music, for which he has won two Oscars and 18 nominations, and his songwriting. “My father, who was not a musician, worshiped his brothers who did (film scoring),” he recalled in a recent NPR interview. “He thought it was the great art form of the century. He kept asking me, no matter what kind of acclaim I got early on for my songs and records, „When are you gonna do a picture?‟ It was like that was the pinnacle of music.” Newman had the unique advantage of growing up on Hollywood sound stages where his celebrated uncles – Alfred, Lionel and Emil – wrote and/or conducted the scores to dozens of films. He could have easily gone into the family business. But at first he resisted, preferring to become a professional songwriter at the age of 17, then an unlikely singer/songwriter. Lucky for us. You can hardly make a better case that songs can be the equal of any art form than the classics on display in The Randy Newman Songbook Vol. 2. The album is essential listening for those who care about American music (not just the popular variety). For younger listeners who might as yet be unfamiliar with his pre-Toy Story repertoire, these tracks might be a revelation. In the late 1960s world of confessional, mostly guitar-strumming singer-songwriters, Newman always stood apart: for his symphonic vision, backed up with superb arranging chops, as well as for the literary ambitions of his lyrics, mostly written from the point of view of unreliable narrators, sometimes tragic, more often ironic and mordantly funny. -

Brave: the New Face of Princesses? by Aisling Breen May 2015

Brave: The New Face of Princesses? By Aisling Breen May 2015 Page | 1 This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfilment of the BA (Hons) Film degree at Dublin Business School. I confirm that all work included in this thesis is my own unless indicated otherwise. Aisling Breen May 2015 Supervisor: Barnaby Taylor Page | 2 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the help, contribution and support from the following people. I would not have been able to complete this without them: Barnaby Taylor Martin Breen Siobhan Breen Jason Muddiman Shane Hegarty The Disney Store Cast Members DBS Library Brenda Chapman Mark Andrews Thank you so much for your help and support. I appreciate every bit of it. Page | 3 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Page Introduction 5 The History of Animation 6 Chapter 2 Animation 11 Background of the Company 15 Chapter 3 Origins of Brave 19 Chapter 4 The Film 23 About Brave 27 Chapter 5 Responses to the Film 30 To Change or Not to Change 33 Chapter 6 Conclusion 36 References 43 Bibliography 45 Filmography 48 Page | 4 Chapter 1 Introduction The Pixar Animation Studios have been around for many years and in those years it has made some outstanding feature and short films. It has exchanged hands three times but has kept its flare and individuality. It is the company that has created some ground breaking technology that has changed how animation looks and is received today. It is the company that is making history for all the right reasons and makes childhood memorable and creating memories for the adults. -

Pdf, 328.17 KB

00:00:00 Music Music Gentle, trilling music with a steady drumbeat plays under the dialogue. 00:00:01 Promo Promo Speaker: Bullseye with Jesse Thorn is a production of MaximumFun.org and is distributed by NPR. [Music fades out.] 00:00:12 Jesse Host I’m Jesse Thorn. It’s Bullseye. Thorn 00:00:14 Music Music “Huddle Formation” from the album Thunder, Lightning, Strike by The Go! Team plays. A fast, upbeat, peppy song. Music plays as Jesse speaks, then fades out. 00:00:21 Jesse Host It’s a cliché, but it’s also true: Randy Newman doesn’t really need an introduction. [Music begins to fade out to be replaced with “You’ve Got a Friend in Me”.] I mean, I can say Randy Newman to you and you’ll probably start thinking about this. 00:00:31 Music Music “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” by Randy Newman from the movie Toy Story. Sweet, gentle music. You’ve got a friend in me You’ve got a friend in me When the road looks rough ahead And you’re miles and miles… [Music fades into “Short People”] 00:00:44 Jesse Host Or this. 00:00:45 Music Music “Short People” by Randy Newman. Upbeat, fun music. Short people got no reason Short people got no reason Short people got no reason To live… [Music fades into “I Love L.A.”] 00:01:00 Jesse Host Or maybe this. 00:01:02 Music Music “I Love L.A.” by Randy Newman. I love L.A.