'Excavations at the Abbot's House, Dunfermline'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Validation of a Multivariable Prognostic Model To

Edinburgh Research Explorer The development and validation of a multivariable prognostic model to predict foot ulceration in diabetes using a systematic review and individual patient data metaanalyses Citation for published version: The PODUS Group, Crawford, F, Cezard, G, Chappell, F & Sheikh, A 2018, 'The development and validation of a multivariable prognostic model to predict foot ulceration in diabetes using a systematic review and individual patient data metaanalyses', Diabetic Medicine, pp. 1480-1493. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13797 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1111/dme.13797 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Diabetic Medicine General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 DIABETICMedicine DOI: 10.1111/dme.13797 Systematic Review or Meta-analysis The development and validation of a multivariable prognostic model to predict foot ulceration in diabetes using a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analyses F. Crawford1 , G. Cezard2,3 and F. -

Spice Briefing

MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY AND REGION Scottish SESSION 1 Parliament This Fact Sheet provides a list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during the first parliamentary session, Fact sheet 12 May 1999-31 March 2003, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represented. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSPs: Historical MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a Series number of constituencies. 30 March 2007 This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order with the MSP’s name, the party the MSP was elected to represent and the corresponding region. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs elected to represent each region. Abbreviations used: Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats SNP Scottish National Party SSP Scottish Socialist Party 1 MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY: SESSION 1 Constituency MSP Region Aberdeen Central Lewis Macdonald (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen North Elaine Thomson (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen South Nicol Stephen (LD) North East Scotland Airdrie and Shotts Karen Whitefield (Lab) Central Scotland Angus Andrew Welsh (SNP) North East Scotland Argyll and Bute George Lyon (LD) Highlands & Islands Ayr John Scott (Con)1 South of Scotland Ayr Ian -

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Abbotsford Business Park Falkirk, Fk2 7Yz

FOR SALE ABBOTSFORD BUSINESS PARK FALKIRK, FK2 7YZ OFFICE & INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT SITES SITES AVAILABLE FROM 0.34 HA (0.85 ACRES) TO 3.98 HA (9.84 ACRES) www.abbotsfordbusinesspark.co.uk ASDA RDC MALCOLM M9 LOGISTICS A9 ASDA ASDA FALKIRK PLOT 12B PLOT 1A PLOT 1B TOWN CENTRE PLOT 7 PLOT 2 PLOT 9 PLOT 3 PLOT 5 PLOT 10 PLOT 4 SOLD PLOT 8 PLOT 6 FALKIRK COUNCIL ABBOTSFORD BUSINESS PARK FALKIRK, FK2 7YZ LOCATION DESCRIPTION The town of Falkirk occupies a central position The business park comprises of circa 11.7 ha (29 acres) of in Scotland with a good proximity to Edinburgh brownfield land formerly occupied by Alcan and used in the processing of aluminium. The site has been cleared, and Glasgow international airports and the Port remediated and new services provided with assistance at Grangemouth. Glasgow lies 23 miles to the from European Regional Development Funding. The site south west, Edinburgh 25 miles to the south offers excellent potential for commercial development due east and Stirling is situated just 12 miles to to the immediate access to main vehicular routes servicing the Falkirk area. Considerable improvement works are the west. Falkirk has 2 railway stations which being undertaken to Junctions 5 and 6 on the M9 improving connect to both Edinburgh and Glasgow and travel times to the rest of the national motorway network. there is a daily direct service to London King’s Additionally, the prominent position of the site adjacent Cross as well as the Caledonian Sleeper which to the A9 offers the opportunity to create a highly visible runs to London Euston. -

Community Bulletin

Community EDITION 42 #Support DG Friday 23 October 2020 Autumnal leaves in Dock Park, Dumfries Inside Business Hardship Fund Take Be Kind Connect Notice Support Give Do you know your region? www.dumgal.gov.uk/supportdg Scarecrows Tel 030 33 33 3000 Welcome to Community Your Dumfries and Galloway Community Bulletin Cllr Elaine Murray Cllr Rob Davidson Council Leader Depute Leader Hello, and welcome to issue 42 of your Community Bulletin. The Covid-19 pandemic has brought us all unprecedented circumstances and unforeseen challenges. As 2020 dawned, none of us could have anticipated what lay ahead of us. All of us have been affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, experienced hardships, and made sacrifices. For some, life will never return to what was regarded as ‘normal’ prior to the pandemic. Now, temperatures are dropping, daylight hours are shortening, and the clocks go back this weekend. Clearly, winter is almost upon us. Unfortunately, during the winter months, we’ll face an upsurge in Covid-19 cases, with the added challenges of incidences of flu. As the numbers of Covid-19 cases, hospital admissions and deaths rise again across Scotland, sadly there have been several deaths in a Dumfries care home this week. Our sincere sympathies go to all those bereaved. The Scottish Government is now exploring the possibility of a multiple-tier system, involving differing levels of restrictions that can be applied nationally or regionally, depending on levels of infection. Whatever the outcome, we urge you to comply with the restrictions set and take all available precautions to protect the wellbeing of you and your loved ones. -

HORSE in TRAINING, Consigned by Attwater Racing Ltd. the Property of Shiremark Barn Stables Ltd

HORSE IN TRAINING, consigned by Attwater Racing Ltd. The Property of Shiremark Barn Stables Ltd. Lot 1 (With VAT) Sadler's Wells Montjeu Floripedes Camelot (GB) Kingmambo ENYAMA (GER) Tarfah April 20th, 2016 Fickle Red Ransom Bay Filly Ransom O'War (Fourth Produce) Ella Ransom (GER) Sombreffe (2007) Dashing Blade Earthly Paradise Emy Coasting E.B.F. Nominated. ENYAMA (GER): ran twice at 3 years, 2019. Sold as she stands (see Conditions of Sale). FLAT 2 starts LAST THREE STARTS (prior to compilation) 22/02/19 6/7 Class 5 (WFA AWT Novice) Lingfield Park 1m 4f 16/01/19 8/8 Class 6 (WFA AWT Maiden) Lingfield Park 1m 4f 1st dam ELLA RANSOM (GER): winner at 4 years in Germany and placed 3 times; dam of a winner from 3 runners and 5 foals: Eyla (GER) (2013 f. by Shirocco (GER)): winner at 3 years in Germany and placed 3 times. Eyra (IRE) (2014 f. by Campanologist (USA)): placed 3 times at 3 and 4 years, 2018 in Germany. Enyama (GER) (2016 f. by Camelot (GB)): see above. Eisenherz (GER) (2017 c. by Kamsin (GER)): unraced to date. 2nd dam EARTHLY PARADISE (GER): winner at 3 years in Germany and £12,545; Own sister to Easy Way (GER); dam of 6 winners inc.: EARL OF TINSDAL (GER) (c. by Black Sam Bellamy (IRE)): Jt Champion older horse in Italy in 2012, 6 wins in Germany and in Italy and £522,909 inc. Gran Premio del Jockey Club, Milan, Gr.1, Gran Premio di Milano, Milan, Gr.1 and Rheinland-Pokal, Cologne, Gr.1, 2nd Deutsches Derby, Hamburg, Gr.1, Grosser Preis von Berlin, Berlin-Hoppegarten, Gr.1, Preis von Europa, Cologne, Gr.1; sire. -

Sub-Council Area Projections

The following slides presented some provisional results to the Projections Sub-Group in August 2015. However, the results have been superseded by the NRS publication of Population and Household Projections for Scottish Sub-council Areas on 23 March 2016. Sub-Council Area Projections Angela Adams Population and Migration Statistics NRS August 2015 About me - Angela Adams • Seconded to National Records of Scotland for 10 months from June 2015 to March 2016 to work on Small Area Projections project • Background – Strategic Town Planner for Clydeplan, the Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Strategic Development Planning Authority • We produce a 5 year development plan covering cross-boundary issues for 8 local authorities East & West Dunbartonshire, East Renfrewshire & Renfrewshire, Glasgow City, Inverclyde, North and South Lanarkshire • My responsibility was strategic housing issues, essentially how many houses do we need and where are they going to go • Recently completed the second Housing Need and Demand Assessment and this is being taken through the second Strategic Development Plan which will be published in January 2016 for consultation Outline • Developing the methodology • Assumptions • Results of test council area 2012-based population projections • Next Steps Developing the Methodology • Previous work and Research Findings • POPGROUP overview • POPGROUP model • Stages of POPGROUP Aware that some councils undertake their own projections so please feel free to contribute your own experiences throughout the presentation Previous Work • Projections for small areas of Scotland below council area level are not produced by NRS, except for the national parks. • In 2010 NRS carried out research with Professor Ludi Simpson from the Cathie Marsh Centre for Census and Survey Research (CCSR) at the University of Manchester into the demographic data needed to allow councils and health boards to produce population projections at small area level. -

To See Full CV Click Here

Pauline McGee BA (Hons) Fine Art [email protected] www.paulinemcgee.com Born Greenock, Inverclyde, Scotland Education 1978 – 1982 Glasgow School of Art B.A. Hons. Fine Art (Drawing and Painting) 1986 – 1987 Hertfordshire College of Art. Post Graduate Diploma. Art Therapy St. Albans 1993 – 1995 Strathclyde University, Post Graduate Diploma. Person– Glasgow Centered Counselling 1998 – 1999 Dundee University Certificate in Child Protection Studies 2002 – 2004 BACP Counsellor Accreditation Employment 2014 – Present Self-employed artist 2008 – 2014 Manager, Safe Space Support Service Dunfermline, Fife 2006 – 2008 Coordinator for young people, Fife Fife Domestic & Sexual Abuse Partnership 2004 – 2006 Lecturer, MSc Art Therapy, Queen Margaret Edinburgh University 2003 – 2004 Assistant Animator, West Highland Animation Balquidder 1998 – 2003 Development Officer, Open Secret Falkirk 1999 – 2001 Course Co-ordinator, Art Therapy Certificate Glasgow (part-time) Course, Glasgow University 1994 – 1998 Development Worker, Parent Support Project, Falkirk Social Work Services 1996 – 1997 Art Therapist, Dunblane Support Service, Dunblane (sessional) Stirling Council 1990 – 1994 Art Therapist, Aberlour Childcare Trust Stirling 1987 – 1990 Project Worker, Langlees Family Centre Falkirk 1985 – 1986 Support Worker, West Lambeth Health London Authority Solo Exhibitions 2020 100 Four Letter Words, St Martins Community Centre, Guernsey, CI 2019 Stories of Pitlochry, Melt Gallery, Pitlochry, Perthshire 2018 Stories of Pitlochry, Melt Gallery, Pitlochry, Perthshire -

Region Club Firstname Surname

SIGBI Belfast 2020 - Members Delegate List Region Club FirstName Surname Bangladesh Dhaka Shamim Matin Chowdhury Tahsin Farzana Nasrin Fowzia Nazmunnessa Mahtab Aniqa Naorin Arifa Rahman Yasmin Rahman Hasina Zaman Dhanmondi Zakia Sultana Shahid Caribbean Anaparima Lorraine Acosta Malini Bachan Meera Ramona Gopaul Candace Maharaj Susan Umraw-Roopnarinesingh Associate Member Hazel Roberts Barbados Nikita Gibson Debra Joseph Krystle Maynard Ramona Smart Sisporansa Stanford Akilah Sue Judith Toppin Lisa Toppin-Corbin Marguerite Woodstock-Riley Chaguanas Christine Cole Esperance Cheryl Boodoosingh Marilyn De castro-lalla Denyse Ewe Jamestown Andrea Denise Farmer Ian Graham Barbara Taylor Bonita Wharton Jamaica (Kingston) Sonia Black Ellen Campbell-Grizzle Maxine Wedderburn Newtown Chevonne Agana Annisa Attzs Marissa Irma Bubb Anika Gellineau Corina Hernandez de Marhue Isshad John Kandice Spencer Providenciales Betty Dean Rachel Taylor St Vincent and the Grenadines Kathryn Cyrus Christine da Silva Lavinia Mary Vincent Gunn Nicola Williams San Fernando Terry Amirali-Rambharat Sandra Dieffenthaller Aruna Harbaran Sabita Harrikissoon Hazel Hassanali Cheshire North Wales And Wirral Anglesey Marilyn Blackburn Barbara Edwina Dixon Rhiannon Jones Gillian Parry Janet Mary Reid Susan Frances Roberts Rosalind Taylor Bangor and District Sheena Joyce Renner Giudrun Christine Rieck Diane Wynne Davies Bebington Pam Geraldine Cheesley-Hollinshead Barbara Mayers Penelope Nicholas Birkenhead Diane Bennett Chester Geraldine Garrs Susan Haywood Anne MacDonald -

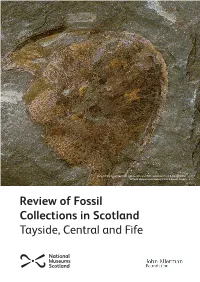

Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife

Detail of the Lower Devonian jawless, armoured fish Cephalaspis from Balruddery Den. © Perth Museum & Art Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Perth Museum and Art Gallery (Culture Perth and Kinross) The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum (Leisure and Culture Dundee) Broughty Castle (Leisure and Culture Dundee) D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum and University Herbarium (University of Dundee Museum Collections) Montrose Museum (Angus Alive) Museums of the University of St Andrews Fife Collections Centre (Fife Cultural Trust) St Andrews Museum (Fife Cultural Trust) Kirkcaldy Galleries (Fife Cultural Trust) Falkirk Collections Centre (Falkirk Community Trust) 1 Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Collection type: Independent Accreditation: 2016 Dumbarton Road, Stirling, FK8 2KR Contact: [email protected] Location of collections The Smith Art Gallery and Museum, formerly known as the Smith Institute, was established at the bequest of artist Thomas Stuart Smith (1815-1869) on land supplied by the Burgh of Stirling. The Institute opened in 1874. Fossils are housed onsite in one of several storerooms. Size of collections 700 fossils. Onsite records The CMS has recently been updated to Adlib (Axiel Collection); all fossils have a basic entry with additional details on MDA cards. Collection highlights 1. Fossils linked to Robert Kidston (1852-1924). 2. Silurian graptolite fossils linked to Professor Henry Alleyne Nicholson (1844-1899). 3. Dura Den fossils linked to Reverend John Anderson (1796-1864). Published information Traquair, R.H. (1900). XXXII.—Report on Fossil Fishes collected by the Geological Survey of Scotland in the Silurian Rocks of the South of Scotland. -

Lot 648 the Property of Mr

FROM PARKWAY FARM LOT 648 THE PROPERTY OF MR. DENIS McDONNELL 648 Busted Bustino Supreme Leader Ship Yard BAY GELDING Princess Zena Habitat (IRE) Guiding Light May 5th, 2001 Sabrehill Diesis (Second Produce) Janet Lindup (GB) Gypsy Talk (1995) Tartan Pimpernel Blakeney Strathcona E.B.F. Nominated. 1st dam JANET LINDUP (GB): placed twice at 3 years, 2nd Century 106 FM Handicap, Nottingham and 3rd Hull Daily Mail Handicap, Beverley; dam of- Timbavati (IRE) (2000 f. by Royal Applause (GB)): ran once. 2nd dam TARTAN PIMPERNEL: 3 wins at 2 and 3 years and £15,293 inc. Galtres S., York, L., placed 3 times inc. 2nd Argos Star Fillies Mile, Ascot, Gr.3 and 4th Park Hill S., Doncaster, Gr.2; dam of 7 winners: ELUSIVE (f. by Little Current (USA)): winner at 2 years and £7545, Acomb S., York, L., placed once; dam of 3 winners: HOPSCOTCH (f. by Dominion): placed 3 times at 2 years; also 11 wins over hurdles and £48,514 inc. Finale Junior Hurdle, Chepstow, L. and Food Brokers Finesse 4yo Hurdle, Cheltenham, L., placed once and placed 10 times over jumps in U.S.A. and £17,842 inc. 2nd Metcalf Memorial Cup H'cap Steeplechase, Red Bank, L., Crown Royal H. Hurdle, Pine Mountain, L., 3rd Metcalf Memorial Cup H'cap Steeplechase, Red Bank, L. and Crown Royal H. Hurdle, Pine Mountain, L.; broodmare. Sheriffmuir (GB): 7 wins, £27,652: 2 wins at 3 years and £5293 and placed once; also 5 wins over hurdles and £22,359 and placed 6 times inc.