Activism in 1930S Fremantle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Assembly Questions on Notice

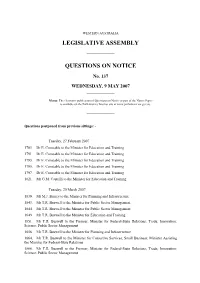

WESTERN AUSTRALIA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY QUESTIONS ON NOTICE No. 137 WEDNESDAY, 9 MAY 2007 Memo: The electronic publication of Questions on Notice as part of the Notice Paper is available on the Parliament’s Internet site at www.parliament.wa.gov.au. Questions postponed from previous sittings: - Tuesday, 27 February 2007 1783. Dr E. Constable to the Minister for Education and Training 1791. Dr E. Constable to the Minister for Education and Training 1793. Dr E. Constable to the Minister for Education and Training 1795. Dr E. Constable to the Minister for Education and Training 1797. Dr E. Constable to the Minister for Education and Training 1821. Mr G.M. Castrilli to the Minister for Education and Training Tuesday, 20 March 2007 1839. Mr M.J. Birney to the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure 1843. Mr T.R. Buswell to the Minister for Public Sector Management 1844. Mr T.R. Buswell to the Minister for Public Sector Management 1849. Mr T.R. Buswell to the Minister for Education and Training 1851. Mr T.R. Buswell to the Premier; Minister for Federal-State Relations; Trade; Innovation; Science; Public Sector Management 1858. Mr T.R. Buswell to the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure 1864. Mr T.R. Buswell to the Minister for Corrective Services; Small Business; Minister Assisting the Minister for Federal-State Relations 1866. Mr T.R. Buswell to the Premier; Minister for Federal-State Relations; Trade; Innovation; Science; Public Sector Management 1868. Mr T.R. Buswell to the Minister representing the Minister for Agriculture and Food; Forestry; the Mid West and Wheatbelt; Great Southern 1870. -

Examining Perth's Performing Arts Infrastructure

Examining Perth’s Performing Arts Infrastructure Actions to position Perth as a global leader in the arts June 2013 About the Committee for Perth The Committee for Perth is a member funded think tank focused on maintaining and improving the liveability of the Perth metropolitan region by ensuring its vibrancy, economic prosperity, cultural diversity and sustainability. We currently have over 90 members representing a broad cross sector of the business community, civic institutions and local government and rely solely on our members’ financial contribution to enable us to undertake the work, research and activities that we do. A full membership listing is included as Appendix F. The role of the Committee for Perth is to advocate on issues that we believe will help us realise our vision for Perth and we have developed a unique model of advocacy through which this is achieved. Regardless of whether a project is our initiative or one implemented by government or others, we remain informed advocates for projects that we believe will benefit future Perth whatever stage they are at in concept or development. Further information about the Committee for Perth and our work can be obtained from our website at www.committeeforperth.com.au This report is the copyright of the Committee for Perth. While we encourage its use, it should be referenced as : (2013) Examining Perth’s Performing Arts Infrastructure, The Committee for Perth, Perth Foreword In late 2008 the Committee for Perth released its landmark report A Cultural Compact for Western Australia, -

Burwell-Frederick-William

PHOTO REQUIRED Frederick W. Burwell (courtesy xx xx) Frederick William Burwell (1846-1915) was born in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland to Frederick Charles Burwell and Margaret Allan Ross. Unfortunately Frederick senior died in the same year as the birth of his son. F.W. Burwell served his articles with James Matthews (1820-1898) in Scotland before migrating to the southern Dominions, arriving at Melbourne in 1869, aged 23, and subsequently moving to New Zealand. He first established a practice in Queenstown, then moving to Invercargill in 1874, where his practice thrived. The New Zealand Historic Places Trust notes that “Burwell is noted for designing many buildings in Invercargill, which transformed the centre of the town in the 1870s. Once established in Invercargill he began designing elegant two and three-storey buildings, in the Renaissance style. In Dee Street almost all the buildings were designed by him, including the hospital. 'The Crescent' was another notable streetscape created by Burwell.” Frederick Burwell was elected a Fellow of RIBA in 1880, proposed by (later Sir) Robert W. Edis, John Norton, and his uncle David Ross. Ross had also studied under James Matthews, the two architects had both migrated to New Zealand, and Ross had been made FRIBA in 1879 - with Edis and Norton as proposers. Burwell moved to Hawthorn, Victoria and was listed in practice in Collins Street, Melbourne from c.1888 until 1894. A cursory examination of tender notices suggests Burwell undertook a significant number of multiple residential projects in and around Melbourne in this period. Fred married the much younger Annie Sunderland Bateman (1868-1942) at Hobart, Tasmania on 30 April 1891. -

Western Australia), 1900-1950

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2007 An investigation of musical life and music societies in Perth (Western Australia), 1900-1950 Jessica Sardi Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Other Music Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Sardi, J. (2007). An investigation of musical life and music societies in Perth (Western Australia), 1900-1950. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1290 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1290 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. Youe ar reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Melville North

FREMANTLE HVolume 29 No 15 ERALD Your local, INDEPENDENT newspaper 41 Cliff Street, Fremantle Saturday April 14, 2018 Melville North: Letterboxed to Applecross, Alfred Cove, Ardross, Ph: 9430 7727 Fax 9430 7726 www.fremantleherald.com Attadale, Bicton, Booragoon, Brentwood, Melville, Mt Pleasant, Myaree and Palmyra. Email: [email protected] HERALD Tragedy unites us F OTY • Ben French. TIPPING Photo by Anna LITE! Gallagher THIS WEEK’S GAME: West Coast V Gold Coast Saturday, 14 April - OS Visit fremantleherald.com and submit your tips now for your chance to win! WIN A • Locals collect donations for Ben French at the East Freo 1 NIGHT STAY Jetty, close to where his food van Eat No Evil operated. Photo by Alan Holbrook AT QUEST days, 983 people raised just FREMANTLE by KAVI GUPPTA over $94,800. SEE COMPETITIONS WELL-KNOWN Alongside generous Fremantle foodie Ben donations were empowering PAGE FOR DETAILS comments of support. French drew his last Hospitality workers breath in the early hours shared fond memories of of April 10. slinging around fish tacos SOMEWHERE Peace has come to the and canapés with French, beloved gentle giant, who and his mate Ben Foss, in IN THIS co-owned popular food their popular Eat No Evil truck Eat No Evil, after food truck. PAPER IS A he suffered severe head FAKE AD! trauma, multiple broken Sadness bones and punctured organs Find it for your from a scooter accident in The page encouraged us Thailand on March 28. to express our frustrations, chance to win a While French’s accident hope and support, and it feast for two at local and eventual passing has became a virtual town hall favourite, Clancy’s generated significant media reminding us that help is Fish Pub Fremantle. -

Annual Report 2018–19

2018–19 ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS ABOUT US 4 OUR VISION 6 OUR YEAR IN REVIEW Message from the Mayor 7 Message from the CEO 9 OUR ELECTED MEMBERS 11 KINGS SQUARE RENEWAL 13 SERVICE SNAPSHOT 16 HIGHLIGHTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS Awards 18 Looking back—month by month 20 LOOKING AHEAD 30 OUR PEOPLE Executive Leadership Team 32 Our Services 33 OUR GOVERNANCE 58 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Financial Reports 64 Auditors' Reports 75 3 ABOUT FREMANTLE PROFILE Bounded by the Swan River and the Indian Ocean, Fremantle is widely regarded US as Perth’s second city and is home to the state’s busiest and most important cargo port. The port, which has steadily grown from a humble trading post, is now the beating heart of Western Australia’s economy. Fremantle’s unique character is captured by its landscape, heritage architecture, music, arts, culture, festivals, retail stores, markets, cafés and restaurants, which all contribute to its village-style atmosphere OUR PROUD HISTORY Fremantle’s most important assets are its heritage and its people of diverse backgrounds and cultures. Its irresistible character is inviting and rich in history. Fremantle is an important place for Aboriginal people and lies within the Aboriginal cultural region of Beeliar. Its Nyoongar name is Walyalup (the place of walyo) and its local people are known as the Whadjuk people. To the local Whadjuk people, whose heritage dates back tens of thousands of years, Fremantle is a place of ceremonies, significant cultural practices and trading. Walyalup has several significant sites and features in many traditional stories. -

Cogill Brothers

COGILL BROTHERS Charles and Harry Cogill American comics, dancers, singers, entrepreneurs, writers, producers. The Cogill brothers first toured Australia with Emerson's Minstrels in 1885 and remained in the country for some 15 years. During that period they found engagements with Williamson, Garner and Musgrove and Harry Rickards (including operating joint companies), but were largely known for running their own minstrel and burlesque companies. These companies invariably included some of the country's leading performers, notably W. Horace Bent, J. C. Bain, the Bovis brothers, Delohery Craydon and Holland, Johnny Matlock, Slade Murray, the Rockley brothers and Will Whitburn. In 1890 the Cogills were forced into bankruptcy, but within 18 months were able to return to the industry as entrepreneurs. By the mid- 1890s the brothers appear to have taken different paths, with Charles Cogill being associated with Harry Rickards (1896 - ca.1900) and Frank M. Clark (1898). Harry Cogill toured his own minstrel companies (Harry Cogill's Federal Minstrels, Harry Cogill's New Musical Comedy Co, and the Bright Lights Co) around Australasia from 1897 to 1901. Charles died in San Francisco in 1903. His brother died in New York less than a month later. The Cogill brothers, Charles William and Harry Payon, came to Australia in the 1880s during a period of activity and opportunity not seen in the county since the heady gold-rush era of the late 1850s/early 1960s and subsequently stayed. As entrepreneurs they engaged a great number of local performers, and played a significant role in disseminating their knowledge beyond their own troupes, as many of these performers went on to carve out their own successful careers and in turn engaged and developed the next generation of performers. -

Western Australia

Location Name Venue Type Opened Closed Current Status AGNEW Agnew Picture Gardens Open Air c1935-8 c1949 Closed Street Address -> address details required Country Alternative Names -> Agnew Open Air Theatre ........................................................................................................................................................................................ Inc. ALBANY Albany Entertainment Centre Multi-purpose 11/12/2010 Operational Street Address -> 2 Toll Place (off Princess Royal Drive) Country Alternative Names -> Venue includes Princess Royal Theatre (620 seats) ........................................................................................................................................................................................ ALBANY Albany Town Hall Public Hall 1 June 1993 Hall Street Address -> 217 York Street (Cnr. Grey St.) Country Alternative Names -> Town Hall Pictures, Cinema 1 ........................................................................................................................................................................................Australia ALBANY Central 70 Drive In Drive In 26/12/1964 10/02/1983 Industrial Estate Street Address -> Barker Road (opposite Stead St) of Country ........................................................................................................................................................................................ ALBANY Cremorne Gardens Open Air c1896 Destroyed by Street Address -> Stirling Terrace. Country -

Asthma Friendly Schools 2017

Schools Asthma Name of school P/C Trained Friendly Adam Road Primary School 6230 Albany Primary School 6330 Albany Secondary ESC 6330 Albany Senior High School 6330 Al-Hidayah Islamic School 6102 Alinjarra Primary School 6064 Alkimos Baptist College 6030 Alkimos Beach Primary School 6033 Alkimos Primary School 6033 All Saints' College 6149 Allanson Primary School 6225 Allendale Primary School 6530 Alta-1 6065 Amaroo Primary School 6225 Anne Hamersley Primary School 6069 Anzac Terrace Primary School 6054 Applecross Primary School 6153 Applecross Senior High School 6153 Aquinas College 6152 Aranmore Catholic College 6007 Aranmore Catholic Primary School 6007 Arbor Grove Primary School 6069 Ardross Primary School 6153 Armadale ESC 6112 Armadale Primary School 6112 Armadale Senior High School 6112 Ashburton Drive Primary School 6110 Ashdale Primary School 6065 Ashdale Secondary College 6065 Ashfield Primary School 6054 Assumption Catholic Primary School 6210 Attadale Primary School 6156 Atwell College 6164 Atwell Primary School 6164 Aubin Grove Primary School 6164 Augusta Primary School 6290 Aust. Christian College - Darling Downs 6112 Aust. Christian College - Southlands 6330 Aust. Islamic College - Kewdale 6105 Aust. Islamic College - North Of The River 6059 Aust. Islamic College - Perth 6108 Austin Cove Baptist College 6208 Australind Primary School 6233 Australind Senior High School 6233 Aveley Primary School 6069 Avonvale ESC 6401 Avonvale Primary School 6401 Babakin Primary School 6428 Badgingarra Primary -

<001> Reporter

STANDING COMMITTEE ON ESTIMATES AND FINANCIAL OPERATIONS 2016–17 BUDGET ESTIMATES HEARINGS TRANSCRIPT OF EVIDENCE TAKEN AT PERTH WEDNESDAY, 15 JUNE 2016 SESSION ONE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Members Hon Ken Travers (Chair) Hon Peter Katsambanis (Deputy Chair) Hon Alanna Clohesy Hon Rick Mazza Hon Helen Morton __________ Estimates and Financial Operations Wednesday, 15 June 2016 — Session One Page 1 Hearing commenced at 9.30 am Hon PETER COLLIER Minister for Education, examined: Ms SHARYN O’NEILL Director General, examined: Ms JENNIFER McGRATH Deputy Director General, Finance and Administration, examined: Mr JOHN FISCHER Executive Director, Infrastructure, examined: Mr PETER TITMANIS Executive Director, examined: Ms CINDY BARNARD Director, Staff Recruitment and Employment Services, examined: Mr JAY PECKITT Chief Finance Officer, examined: Mr LINDSAY HALE Executive Director, Statewide Services, examined: Mr STEPHEN BAXTER Executive Director, Statewide Planning and Delivery, examined: The CHAIR: On behalf of the Standing Committee on Estimates and Financial Operations, I would like to welcome you to today’s hearing. Can the witnesses confirm that they have read, understood and signed a document headed “Information for Witnesses”? The Witnesses: Yes. The CHAIR: Thank you. It is essential that all your testimony before the committee is complete and truthful to the best of your knowledge. This hearing is being recorded by Hansard and a transcript of your evidence will be provided to you. It is also being broadcast live on the Parliament’s website. The hearing is being held in public, although there is discretion available to the committee to hear evidence in private. If for some reason you wish to make a confidential statement during today’s proceedings, you should request that the evidence be taken in closed session before answering the question. -

Leaders of the Opposition from 1905

Leaders of the Opposition from 1905 From 1905 there have been 33 Leaders of the Opposition in Western Australia. Date Date of Government Leader of the Opposition Date Appointed Retirement from Office 1905 – 1906 Cornthwaite Rason (Lib) Henry Daglish (ALP) 25 August 1905 27 September 1905 25 August 1905 – 7 May 1906 (Served 1 month 2 days) William Dartnell Johnson (ALP) 4 October 1905 27 October 1905 (Served 23 days) 1906 – 1909 Newton Moore (Min) Thomas Henry Bath 22 November 1905 3 August 1910 7 May 1906 – 14 May 1909 (Served 4 years 8 months 12 days) 1910 – 1911 Frank Wilson (Lib) John Scaddan (ALP) 3 August 1910 7 October 1911 16 September 1910 – 7 October 1911 (Served 1 year 2 months 4 Days) 1911 – 1916 John Scaddan (ALP) Frank Wilson (Lib) 1 November 1911 27 July 1914 7 October 1911 – 27 July 1916 (Served 4 years 8 months 26 days) 1916 – 1917 Frank Wilson (Lib) John Scaddan (ALP) 27 July 1916 8 August 1916 27 July 1916 – 28 June 1917 (Served 12 days) William Dartnell Johnson (ALP) 19 September 1916 31 October 1916 (Served 1 month 12 Days) John Scaddan (ALP) 31 October 1916 c.10 April 1917 (Served 5 month 10 days) 1917 – 1919 Henry Lefroy (Lib) Philip Collier (ALP) 9 May 1917 17 April 1924 28 June 1917 – 17 April 1919 (Served 6 years 11 months 8 day) & 1919 – 1919 Hal Colbatch (Lib) 17 April 1919 - 17 May 1919 & 1919 – 1924 Sir James Mitchell (Lib) 17 May 1919 – 15 April 1924 1924 – 1930 Philip Collier (ALP) Sir James Mitchell (Lib) 17 April 1924 24 April 1930 16 April 1924 – 23 April 1930 (Served 6 years 7 days) 1930 – 1933 Sir James -

PR7886 ABC Programmes, 1970-1979

PR7886 ABC Programmes, 1970-1979 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia Date Venue Artist Programme Notes Series Dup 1970 Orchestral concert season 1970 25 Jan 1970 Supreme Court Gardens West Australian Special free Concert Symphony Orchestra 15 Feb 1970 Supreme Court Gardens West Australian Free Festival Concert Symphony Orchestra 7 Mar 1970 Winthrop Hall West Australian Festival Orchestral Symphony Orchestra Concert 13-14 Mar 1970 Winthrop Hall West Australian Orchestral concert Nelli Shkolnikova 1st concert of D Symphony Orchestra season (violin) 1970 subscription series 19 Mar – 1 April Winthrop Hall, Claremont West Australian Free Youth concerts Teachers’ College, Bentley Symphony Orchestra Institute of Technology 25-26 Mar 1970 Winthrop Hall West Australian St Matthew Passion University Choral D Symphony Orchestra Bach Society 7-10 Apr 1970 Geraldton Town Hall, West Australian Country Concert Moora Town Hall, Corrigin Symphony Orchestra Orchestral Tour PR7886 1970-1979 1 Copyright SLWA 2009 Date Venue Artist Programme Notes Series Dup Town Hall, Kalgoorlie Town Hall 7-10 Apr 1970 Geraldton Town Hall, West Australian Free School’s Moora Town Hall, Corrigin Symphony Orchestra Concert Town Hall, Kalgoorlie Town Hall 2 May 1970 Government House Lili Kraus Ballroom 5 May 1970 Winthrop Hall West Australian Symphony Orchestra 15-16 May 1970 Winthrop Hall West Australian Raymond Myers Second concert of D Symphony Orchestra (baritone) 1970 subscription series 12-13 June 1970 Winthrop Hall West Australian Agustin Anievas D Symphony Orchestra (piano) Third concert of 1970 subscription series 16 June 1970 Winthrop Hall West Australian Symphony Orchestra 26-27 June 1970 Winthrop Hall West Australian Suite in ‘G,’ Mass ‘St.