The Iken Cross-Shaft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

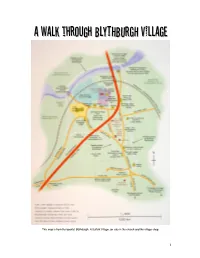

Awalkthroughblythburghvi

AA WWAALLKK tthhrroouugghh BBLLYYTTHHBBUURRGGHH VVIILLLLAAGGEE Thiis map iis from the bookllet Bllythburgh. A Suffollk Viillllage, on salle iin the church and the viillllage shop. 1 A WALK THROUGH BLYTHBURGH VILLAGE Starting a walk through Blythburgh at the water tower on DUNWICH ROAD south of the village may not seem the obvious place to begin. But it is a reminder, as the 1675 map shows, that this was once the main road to Blythburgh. Before a new turnpike cut through the village in 1785 (it is now the A12) the north-south route was more important. It ran through the Sandlings, the aptly named coastal strip of light soil. If you look eastwards from the water tower there is a fine panoramic view of the Blyth estuary. Where pigs are now raised in enclosed fields there were once extensive tracts of heather and gorse. The Toby’s Walks picnic site on the A12 south of Blythburgh will give you an idea of what such a landscape looked like. You can also get an impression of the strategic location of Blythburgh, on a slight but significant promontory on a river estuary at an important crossing point. Perhaps the ‘burgh’ in the name indicates that the first Saxon settlement was a fortified camp where the parish church now stands. John Ogilby’s Map of 1675 Blythburgh has grown slowly since the 1950s, along the roads and lanes south of the A12. If you compare the aerial view of about 1930 with the present day you can see just how much infilling there has been. -

To Blythburgh, an Essay on the Village And

AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) Alan Mackley Blythburgh 2020 AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) INTRODUCTION Margaret Janet Becker (1904-1953) was the daughter of Harry Becker, painter of the farming community and resident in the Blythburgh area from 1915 to his death in 1928, and his artist wife Georgina who taught drawing at St Felix school, Southwold, from 1916 to 1923. Janet appears to have attended St Felix school for a while and was also taught in London, thanks to a generous godmother. A note-book she started at the age of 19 records her then as a London University student. It was in London, during a visit to Southwark Cathedral, that the sight of a recently- cleaned monument inspired a life-long interest in the subject. Through a friend’s introduction she was able to train under Professor Ernest Tristram of the Royal College of Art, a pioneer in the conservation of medieval wall paintings. Janet developed a career as cleaner and renovator of church monuments which took her widely across England and Scotland. She claimed to have washed the faces of many kings, aristocrats and gentlemen. After her father’s death Janet lived with her mother at The Old Vicarage, Wangford. Janet became a respected Suffolk historian. Her wide historical and conservation interests are demonstrated by membership of the St Edmundsbury and Ipswich Diocesan Advisory Committee on the Care of Churches, and she was a Council member of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. -

Joint Cabinet Crisis Kingdom of Mercia

Joint Cabinet Crisis Kingdom of Mercia Hamburg Model United Nations “Shaping a New Era of Diplomacy” 28th November – 1st December 2019 JCC – Kingdom of Mercia Hamburg Model United Nations Study Guide 28th November – 1st December Welcome Letter by the Secretary Generals Dear Delegates, we, the secretariat of HamMUN 2019, would like to give a warm welcome to all of you that have come from near and far to participate in the 21st Edition of Hamburg Model United Nations. We hope to give you an enriching and enlightening experience that you can look back on with joy. Over the course of 4 days in total, you are going to try to find solutions for some of the most challenging problems our world faces today. Together with students from all over the world, you will hear opinions that might strongly differ from your own, or present your own divergent opinion. We hope that you take this opportunity to widen your horizon, to, in a respectful manner, challenge and be challenged and form new friendships. With this year’s slogan “Shaping a New Era of Democracy” we would like to invite you to engage in and develop peaceful ways to solve and prevent conflicts. To remain respectful and considerate in diplomatic negotiations in a time where we experience our political climate as rough, and to focus on what unites us rather than divides us. As we are moving towards an even more globalized and highly military armed world, facing unprecedented threats such as climate change and Nuclear Warfare, international cooperation has become more important than ever to ensure peace and stability. -

The Settlement of East and West Flegg in Norfolk from the 5Th to 11Th Centuries

TITLE OF THESIS The settlement of East and West Flegg in Norfolk from the 5th to 11th centuries By [Simon Wilson] Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted For the Degree of Masters of Philosophy Year 2018 ABSTRACT The thesis explores the –by and English place names on Flegg and considers four key themes. The first examines the potential ethnicity of the –bys and concludes the names carried a distinct Norse linguistic origin. Moreover, it is acknowledged that they emerged within an environment where a significant Scandinavian population was present. It is also proposed that the cluster of –by names, which incorporated personal name specifics, most likely emerged following a planned colonisation of the area, which resulted in the takeover of existing English settlements. The second theme explores the origins of the –by and English settlements and concludes that they derived from the operations of a Middle Saxon productive site of Caister. The complex tenurial patterns found between the various settlements suggest that the area was a self sufficient economic entity. Moreover, it is argued that royal and ecclesiastical centres most likely played a limited role in the establishment of these settlements. The third element of the thesis considers the archaeological evidence at the –by and English settlements and concludes that a degree of cultural assimilation occurred. However, the presence of specific Scandinavian metal work finds suggests that a distinct Scandinavian culture may have survived on Flegg. The final theme considers the economic information recorded within the folios of Little Domesday Book. It is argued that both the –by and English communities enjoyed equal economic status on the island and operated a diverse economy. -

Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England a Revised

BEDE'S ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY OF ENGLAND A REVISED TRANSLATION WITH INTRODUCTION, LIFE, AND NOTES BY A. M. SELLAR LATE VICE-PRINCIPAL OF LADY MARGARET HALL, OXFORD LONDON GEORGE BELL AND SONS 1907 EDITOR'S PREFACE The English version of the "Ecclesiastical History" in the following pages is a revision of the translation of Dr. Giles, which is itself a revision of the earlier rendering of Stevens. In the present edition very considerable alterations have been made, but the work of Dr. Giles remains the basis of the translation. The Latin text used throughout is Mr. Plummer's. Since the edition of Dr. Giles appeared in 1842, so much fresh work on the subject has been done, and recent research has brought so many new facts to light, that it has been found necessary to rewrite the notes almost entirely, and to add a new introduction. After the appearance of Mr. Plummer's edition of the Historical Works of Bede, it might seem superfluous, for the present at least, to write any notes at all on the "Ecclesiastical History." The present volume, however, is intended to fulfil a different and much humbler function. There has been no attempt at any original work, and no new theories are advanced. The object of the book is merely to present in a short and convenient form the substance of the views held by trustworthy authorities, and it is hoped that it may be found useful by those students who have either no time or no inclination to deal with more important works. Among the books of which most use has been made, are Mr. -

ARCHAEOLOGY in SUFFOLK ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS, 1980� Compiled by Edward Martin, Judith Plouviez and Hilary Ross

ARCHAEOLOGY IN SUFFOLK ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS, 1980 compiled by Edward Martin, Judith Plouviez and Hilary Ross Once again this is a selection of the new sites and finds discovered during the year. All the siteson this list have been incorporated into the County's Sites and Monuments Index; the reference to this is the final number given in each entry, preceded by the abbreviation S.A.U. Information for this list has been contributed by Miss E. Owles, Moyses Hall Museum; Mr C. Pendleton, Mildenhall Museum; Mr A. Pye, Lowestoft Archaeological Society; and Mr D. Sherlock. The drawings of the axes from Covehithe were kindly supplied by Mr P. Durbridge. Abbreviations: I. M. Ipswich Museum L.A.S. Lowestoft Archaeological and Local History Society M.H. MoysesHall Museum, Bury St Edmunds M.M. Mildenhall Museum S.A.U. Suffolk Archaeological Unit, Shire Hall, Bury St Edmunds T.M. Thetford Museum Pa Palaeolithic AS Anglo-Saxon Me Mesolithic MS Middle Saxon Ne Neolithic LS Late Saxon BA Bronze Age Md Medieval IA Iron Age PM Post-Medieval RB Romano-British UN Period unknown Aldringham (TM/4760). Ne. Flaked flint axe, found in a garden several years ago. (F. B. Macrae; S.A.U. ARG 008). Aldringham (TM/4759). Md. The disturbed remain.s of a skeleton, lying in an east-west grave, were found in a gas mains service trench at the end of the archway between the Thorpeness Almshouses. At least one other skeleton was intact beneath it and there may have been more. These are probably associated with the medieval St Mary's Chapel, Thorpe, which formerly existed in that area. -

Eastern Region Bedfordshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2008 Evaluations Eastern Region Bedfordshire Bedford (C.09.834/2008) TL04275002 Parish: Bedford Postal Code: MK402QR FORMER ST. BEDE’S SCHOOL, BROMHAM ROAD Former St. Bede’s School, Bromham Road, Bedford: Archaeological Trial Trenching Gregson, R Bedford : Albion Archaeology, Report: SB1352 2008, 26pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Albion Archaeology An evaluation at the site of a proposed residential development at the former St. Bede’s School site was undertaken. The site was located within an area of archaeological potential and was nearby to the site of Greyfriars Friary and to the south, a possible medieval moated site. Archaeological features were found in three of the four trial trenches comprising several post holes, pits, linear features and structural remains. All features were dated by artefact or circumstantial evidence to the post-medieval or modern periods. The evidence from the trial trenching suggested that the site of the proposed housing development area contained little or no significant archaeological remains. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: UD, MD OASIS ID: albionar1-49420 (C.09.835/2008) TL01915705 Parish: Bletsoe Postal Code: MK441RZ LAND ADJACENT TO TWINWOODS BUSINESS PARK, THURLEIGH ROAD, MILTON ERNEST Land Adjacent to Twinwoods Business Park, Thurleigh Road, Milton Ernest, Archaeological Field Evaluation Lodoen, A Bedford : Albion Archaeology, Report: TW1351 2008, 17pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Albion Archaeology The evaluation revealed the remains of Early to Middle Iron Age trackside ditches and a gully, a post-medieval boundary ditch and pit and a number of undated, but possibly Iron Age features. -

Blythburgh Parish N Ew S

B LY T H BU RG H P ARISH N EWS Issue 52 www.onesuffolk.co.uk/blythburghPC May/July 2010 On the starting blocks for Olympic party It is all systems go for Blythburgh Parish Council‟s London 2012 Olympic celebration on theRaise White aHart glass together to with Blythburgh pool and boules July 25 this year. Through the county council, tournaments.A new look annual The Hart parish will meeting also make will a be good held in Celebrating Blythburgh has been granted £400 startingthe village point hall for at guided7.30pm ri onver May bank 19. walks Please for its part in the county-wide Suffolk Open escortedmake a real by Cliffeffort Waller to come. and TheAdam purpose Burrows is toand Weekend. Additional funding is coming from the boatensure rides parishioners on the river are provided fully aware by Naturalof what is parish council and Blythburgh Latitude Trust. England.going on and what is being done in their name. This year, all the parish groups have been invited The day, designed to appeal to young and old, Blythburghto mount a small Parish display Council of their has year‟s regretfully work. will feature a wide range of events held in Holy acceptedThere will the be resignations plenty of opportunity of Binny Lewis for informal and Trinity, The Priory gardens, The White Hart, the Robertdiscussions Benson. over Binny a glass was of thewine driving and light force bites Village Hall, the river and the river bank. The behindprovided the by Parish the parishCouncil‟s council. desire It isto ho improveped that day starts with a community service in Holy safetythis will on ensurethe A 12that and everybody around the in thevillage. -

MAP BOOKLET Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies

MAP BOOKLET to accompany Issues and Options consultation on Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies Local Plan Document Consultation Period 15th December 2014 - 27th February 2015 Suffolk Coastal…where quality of life counts Woodbridge Housing Market Area Housing Market Settlement/Parish Area Woodbridge Alderton, Bawdsey, Blaxhall, Boulge, Boyton, Bredfield, Bromeswell, Burgh, Butley, Campsea Ashe, Capel St Andrew, Charsfield, Chillesford, Clopton, Cretingham, Dallinghoo, Debach, Eyke, Gedgrave, Great Bealings, Hacheston, Hasketon, Hollesley, Hoo, Iken, Letheringham, Melton, Melton Park, Monewden, Orford, Otley, Pettistree, Ramsholt, Rendlesham, Shottisham, Sudbourne, Sutton, Sutton Heath, Tunstall, Ufford, Wantisden, Wickham Market, Woodbridge Settlements & Parishes with no maps Settlement/Parish No change in settlement due to: Boulge Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Bromeswell No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Burgh Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Capel St Andrew Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Clopton No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Dallinghoo Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Debach Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Gedgrave Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Great Bealings Currently working on a Neighbourhood -

Church and Society in Twelfth-Century� Suffolk: the Charter Evidence'

CHURCH AND SOCIETY IN TWELFTH-CENTURY SUFFOLK: THE CHARTER EVIDENCE' by CHRISTOPHER HARPER-BILL, B.A , PH D., ER.HIST.S. EVERY LOCAL HISTORIAN is well aware of the great value of charters, or title deeds; they are an invaluable source of information for genealogy, topography and the descent of estates. Those familiar with late medieval and early modern documents might, however, be excused for thinking them useful but tedious, couched as they are in stereotyped legal formulae. This is certainly not the case with 12th-century charters. It is not merely that in the period up to 1250 the student of diplomatic can trace the gradual evolution of important legal concepts relating to tenure and inheritance. These early charters also abound in colourful and intimate detail, and often reveal the sentiments of donors in a way which, in a later age, is obscured by the strait-jacket of common form. Indeed, it is possible to appreciate more fully the realities of life in the 12th century through charters than through the majority of chronicles.2 The sentiment behind so many gifts to religious houses can be illustrated by two examples relating to the Bigod family, Earls of Norfolk, who held extensive Suffolklands. When Matilda, daughter of Roger Bigod, died, her husband, William d'Albini, weeping and wailing, gave to his newly-founded priory at Wymondham, where she was buried at an impressive ceremony attended by the bishop and the leading ecclesiasticsof the county, the manor of Happisburgh, granted for her salvation and that of all his kindred and of the king and queen. -

2010 January Newsletter

The Felixstowe Society Newsletter Issue Number 93 1 January 2010 Contents 2 The Felixstowe Society 3 Notes from the Chairman & details of the evening Quiz 5 The Seafront Gardens - their history 7 Felixstowe Futures Team in Operation 8 Cottage Hospital Upkeep 1939 11 Award for the Enhancement of the Environment 12 The Felixstowe Quiz 13 National Award for the Abbey Grove Volunteers 14 Research Corner (8) - (the Suffragettes) 17 Beachwatch 2009 18 Visit to Snape Maltings and The Red House 21 Visit to Bawdsey Radar and Sutton Hoo 25 Old Felixstowe - talk by Phil Hadwen 27 Green Print Forum - composting at Foxhall 28 Planning Applications 30 Programme for 2010 Registered Charity No. 277442 Founded 1978 Registered with the Civic Trust The Felixstowe Society is established for the public benefit of people who either live or work in Felixstowe and Walton. Members are also very welcome from the Trimleys and the surrounding villages. The Society endeavours to: stimulate public interest in these areas, promote high standards of planning and architecture and secure the improvement, protection, development and preservation of the local environment. Chairman: Philip Johns, 1 High Row Field, Felixstowe, IP11 7AE, 672434 Vice Chairman: Philip Hadwen, 54 Fairfield Ave., Felixstowe, IP11 9JJ, 286008 Secretary: Trish Hann, 49 Foxgrove Lane, Felixstowe,IP11 7SU, 271902 Treasurer: Susanne Barsby, 1 Berners Road, Felixstowe, IP11 7LF Membership Subscriptions Annual Membership - single £5 Joint Membership - two people at same address £7 Life Membership - single £50 Life Membership - two people at same address £70 Corporate Membership (for local organisations who wish to support the Society) Non - commercial £12 Commercial £15 Young people under the age of 18 Free The subscription runs from the 1 January. -

Parish Precepts and Special Expenses 2019-20

SPECIAL ITEMS - PARISH PRECEPTS AND SPECIAL EXPENSES 2019-20 EQUIVALENT BASIC AMOUNT OF PARISH / AREA EXPENSE TAX BASE COUNCIL TAX COUNCIL TAX £ £ £ Aldeburgh 215,000.00 1,869.81 114.98 281.30 Alderton 6,900.00 177.28 38.92 205.24 Aldringham-Cum-Thorpe 7,500.00 576.82 13.00 179.32 All Saints & St. Nicholas, St. Michael and St. Peter S E 3,000.00 101.25 29.63 195.95 Badingham 9,500.00 219.72 43.24 209.56 Barnby 1,387.75 214.49 6.47 172.79 Barsham and Shipmeadow 1,243.34 130.74 9.51 175.83 Bawdsey 7,650.00 188.48 40.59 206.91 Beccles 114,561.00 3,198.11 35.82 202.14 Benacre 0.00 34.33 0.00 166.32 Benhall & Sternfield 9,000.00 288.33 31.21 197.53 Blaxhall 4,828.98 109.76 44.00 210.32 Blundeston and Flixton 9,021.54 446.39 20.21 186.53 Blyford and Sotherton 3,000.00 72.39 41.44 207.76 Blythburgh 7,550.00 187.24 40.32 206.64 Boulge 0.00 13.91 0.00 166.32 Boyton 2,300.00 61.21 37.58 203.90 Bramfield & Thorington 5,750.00 190.65 30.16 196.48 Brampton with Stoven 3,071.33 145.21 21.15 187.47 Brandeston 3,000.00 144.24 20.80 187.12 Bredfield 5,502.83 149.29 36.86 203.18 Brightwell, Foxhall & Purdis Farm 7,500.00 984.12 7.62 173.94 Bromeswell 4,590.00 157.31 29.18 195.50 Bruisyard 2,900.00 65.85 44.04 210.36 Bucklesham 8,500.00 200.26 42.44 208.76 Bungay 87,312.00 1,628.79 53.61 219.93 Burgh 0.00 81.11 0.00 166.32 Butley, Capel St Andrew & Wantisden 2,798.97 112.68 24.84 191.16 Campsea Ashe 5,500.00 147.02 37.41 203.73 Carlton Colville 54,878.16 2,652.40 20.69 187.01 Charsfield 5,250.00 146.41 35.86 202.18 Chediston, Linstead Magna & Linstead Parva