DONG SOO LEE Ph. D. University of Edinburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12. Hosea 12-14.Indd

ISRAEL’S FINAL YEARS YHWH’S FAITHFUL LOVE HOSEA 12-14 91 Betrayal of the prophetic word 11:12Ephraim has surrounded The English verse numbering follows the Latin me with lies, and the house of Vulgate. The Hebrew, followed by the Greek, Israel with deceit; but Judah numbers the opening verse here as 12:1 – which still walks with God, and is makes the English 12:1-14 the equivalent of the faithful to the Holy One. Hebrew 12:2-15. Verse 11:12 is best understood as a complaint ut- tered by Hosea. The second part of the verse may be a later gloss from a scribe of Judah, or it may be that, having lost all hope for a conversion in Israel, Hosea is looking south to find fidelity. 12:1Ephraim herds the wind, The bulk of verse 1 (verse 2 in Hebrew) speaks and pursues the east wind all of Ephraim’s attempts to do anything Assyria day long; they multiply false- (‘the east wind’) wants (see 2Kings 17:3). The hood and violence. They make last clause reveals attempts to get Egypt on side. a treaty with Assyria, and oil is This suggests the situation in the early years of carried to Egypt. Shalmaneser V, whose reign began in 727. It is possible that ‘Judah’ in verse 2 was a later 2YHWH has an indictment update. Hosea was more likely to have spoken of against Judah, and will punish Israel in this context. In verse 3 Hosea reflects on Jacob according to his ways, the story of the birth of Jacob and Esau, which and repay him according to his describes Jacob (the second twin) as emerging deeds. -

Session 4 (Hosea 9.1-11.11)

Tuesday Evening Bible Study Series #8: The Minor Prophets Session #4: Hosea 9:1 – 11:11 Tuesday, January 24, 2017 Outline A. The Prophecies of Hosea (4:1 – 14:9) 1. Israel’s festivals are condemned (9:1-9) 2. Before and after (9:10 – 11:11) a. The present is like the past (9:10-17) b. The end of cult, king, and calf (10:1-8) c. Sowing and Reaping (10:9-15) d. Israel as God’s wayward child (11:1-11) Notes Israel’s festivals are condemned and Hosea’s Response (9:1-11) • Four important parts of Chapter 9 1. A prophecy of what is coming as a result of God’s departure 2. A proof from the behavior of the people that these things are coming 3. A truncated prayer of Hosea 4. God’s final word on the subject, followed by Hosea’s response. • Hosea condemns Israel’s celebration of their harvest festival as unfaithfulness to the Lord and is denounced. 1. Gathering around threshing floors were features of harvest festivals and occasions for communal worship. Threshing floors were also the site of sexual overtures (Ruth 3). 2. Mourner’s bread – associated with the dead, and is considered unclean. 3. Festival of the Lord = the harvest festival of tabernacles or Sukkoth. 4. The site of Memphis, Egypt (originally Hiku-Ptah), had been the capital of the Old Kingdom. By Hosea’s time it had become a cultural and religious center, but was famous for its ancient tombs. 5. “Sentinel” is often used to refer to prophets. -

Hosea 12:6 – “So You, by the Help of Your God, Return, Hold Fast to Love and Justice, and Wait Continually for Your God.”

Memory Verse: Hosea 12:6 – “So you, by the help of your God, return, hold fast to love and justice, and wait continually for your God.” Icebreaker: When we were children, we all had dreams of incredible skills. If you could be famous for one skill or ability, what would you want to be known for? Why? 1. Martin Luther taught that the Christian life should be a life of repentance. In what way is the recognition of sinfulness crucial to the message of the Gospel? Why is repentance necessary to saving faith in Jesus? What happens if a person doesn’t recognize their sin? 2. Israel looked like it was in great shape as a nation from the outside, yet their hearts were sick. They continued to place their hope in dangerous political alliances rather than God. How were the alliances with Assyria and Egypt a false promise of hope? What are some false promises of hope people commonly look to today? How do these false promises typically end? Digging Deeper: James 1:17 tells us, “Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above…”. How can even a good gift of God become a false source of hope? 3. The Prosperity Gospel is not a new phenomenon. Even back in the time of Hosea, Israel considered their material wealth to be evidence of favor with God (see Hosea 12:8). What causes us to believe good outcomes prove God’s favor? In what way do good outcomes justify the actions taken to arrive there? Go further: How did Israel’s actions in Hosea 12:7 illustrate the false promise of self-preservation? What are some ways people pursue self-preservation at all costs today? 4. -

Melodie Moench Charles, “Book of Mormon Christology”

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 7 Number 2 Article 5 1995 Melodie Moench Charles, “Book of Mormon Christology” Martin S. Tanner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Tanner, Martin S. (1995) "Melodie Moench Charles, “Book of Mormon Christology”," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 7 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol7/iss2/5 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Author(s) Martin S. Tanner Reference Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 7/2 (1995): 6–37. ISSN 1050-7930 (print), 2168-3719 (online) Abstract Review of “Book of Mormon Christology” (1993), by Melodie Moench Charles. Melodie Moench Charles. "Book of Mormon C hris tology." In New Approaches to the Book of Mormon, ed. Brent Lee Metcalfe, 81-114. Salt Lake City: Sig. nature Books, 1993. xiv + 446 pp. $26.95. Reviewed by Martin S. Tanner Book of Mormon Chri stology is not a new subject, but it is an important one. Melodie Moench Charles begin s her essay on the topic with a personal anecdote. She relates how when teaching an adult Sunday School class (presumably Gospel Doctrine) she dis cussed Mos iah 15:1 -4, which she quotes as fo llows: God himself shall come down among the children of men being the Father and the Son- The Father, because he was conce ived by the power of God; and the Son, because of the nesh; th us becoming the Father and the Son-And they are one God, yea, the very Eternal Father of heaven and of earth. -

The Minor Prophets Michael B

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 6-26-2018 A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets Michael B. Shepherd Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shepherd, Michael B., "A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets" (2018). Faculty Books. 201. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets Keywords Old Testament, prophets, preaching Disciplines Biblical Studies | Religion Publisher Kregel Publications Publisher's Note Taken from A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © Copyright 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd. Published by Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, MI. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ISBN 9780825444593 This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE KREGEL EXEGETICAL LIBRARY A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE The Minor Prophets MICHAEL B. SHEPHERD Kregel Academic A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505-6020. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in printed reviews. -

The Book of Joel: Anticipating a Post-Prophetic Age

HAYYIM ANGEL The Book of Joel: Anticipating a Post-Prophetic Age Introduction OF THE FIFTEEN “Latter Prophets”, Joel’s chronological setting is the most difficult to identify. Yet, the dating of the book potentially has significant implications for determining the overall purposes of Joel’s prophecies. The book’s outline is simple enough. Chapters one and two are a description of and response to a devastating locust plague that occurred in Joel’s time. Chapters three and four are a prophecy of consolation predict- ing widespread prophecy, a major battle, and then ultimate peace and pros- perity.1 In this essay, we will consider the dating of the book of Joel, the book’s overall themes, and how Joel’s unique message fits into his likely chronological setting.2 Dating Midrashim and later commentators often attempt to identify obscure figures by associating them with known figures or events. One Midrash quoted by Rashi identifies the prophet Joel with the son of Samuel (c. 1000 B.C.E.): When Samuel grew old, he appointed his sons judges over Israel. The name of his first-born son was Joel, and his second son’s name was Abijah; they sat as judges in Beer-sheba. But his sons did not follow in his ways; they were bent on gain, they accepted bribes, and they subvert- ed justice. (I Sam. 8:1-3)3 RABBI HAYYIM ANGEL is the Rabbi of Congregation Shearith Israel. He is the author of several books including Creating Space Between Peshat & Derash: A Collection of Studies on Tanakh. 21 22 Milin Havivin Since Samuel’s son was wicked, the Midrash explains that he must have repented in order to attain prophecy. -

Oracular Cursing in Hosea 13

ORACULAR CURSING IN HOSEA 13 by PAUL N. FRANKLYN 1709 Welcome Lane, Nashville, TN 37216 Each student of the prophet Hosea is impressed by the profound focus that the cult assumes in the rhetoric of the book. Notable excep tions are Utzschneider ( 1980) and Hentschke ( 1957) who examine traditio historical evidence to argue that Hosea's true foil is the monarchy. The cult, however, is institutionalized according to past scholarship through the speeches of Hosea in three ways: (I) with connections to the fertility cult; (2) with links to the juridical practices acculturated from secular courts; and (3) as a levitical prophet who is trained to search out and destroy cultic apostasy. The speech forms that hypothetically fit the first two settings-dramas or myths of the fertility cult, and oracles of judgment for the city gate-have been well described. The third explana tion, which has gained the most recent adherents, is relatively unsub stantiated with unique or specific speech forms. After a review of past explanations for Hosea's cultic emphasis, this article proposes a new speech form, the "curse oracle," for the levitical prophet opposed to cultic apostasy. A full argument for the curse oracle in Hosea, including a complete textual, form-critical, and traditio historical analysis of Hosea 13, can be found in the author's dissertation (Franklyn, 1986). Connection with the Fertility Cult Hosea is obviously familiar with the cultic practices assigned to the Baca! deities. We are reminded of the influential essay by H. G. May (1932, pp. 76-98), which comes from a period when the religion of Mesopotamia was far too easily paralleled with that of Canaan. -

In the Massoretic Text

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 1935 An Investigation of the Triliteral Root [Baal] in the Massoretic Text Herbert C. Albrecht Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Albrecht, Herbert C., "An Investigation of the Triliteral Root [Baal] in the Massoretic Text" (1935). Graduate Thesis Collection. 243. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/243 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J.Jl I NVESTIGAT I ON OF THE 1'RILITERAL ROOT t )J;J. IN THE MASSORETIC TEXT by Herbert C. Albrecht A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts College of Religion Division of Graduate Instruction Butler Uni·versity Indianapolis 1935 I I ,8t...1. r, !}I./,;}-; '-'• 'do PREFACE r:D <Il I~ oertain important words used in t h e Massoretic Text were studied individually, the several instances of their occurrenoe oompa r ed with each other and each form interpreted in the light of its own setting, Bnd in the light of other similar instances of its usage, t her e can be little dcubt that many useful suggestions would re~ult . All these sugge stions would tend toward a more acourate reproduotion of the original Hebrew in t he English trans lation of t he Bible. -

T3247.Hosea 7-10.021517.Pages

THROUGH THE BIBLE STUDY HOSEA 7-10 The liberal assumption today is that humanity has progressed, or evolved, and is more sophisticated than in years gone by. Moderns are far more enlightened than their ancient counterparts. But this isn’t true. It’s certainly erroneous when it comes to how we view sex. The idea of sexual intimacy as nothing more than a biological function, a physical act, is a modern invention. The ancients viewed sex in a much more sophisticated, even spiritual way. They understood its impact on the human psyche and gave it higher value. They considered sexual intimacy as holy or sacred. Even the pagan cults saw sex as an act of worship. To engage in sexual intimacy was to become one with your partner, and to invite the gods to participate with their blessing. This is why nearly all the pagan temples employed sex workers - prostitutes called priestesses - to engage in sex as a religious ritual. The act of sex was seen as a spiritual experience. You became one with the other person, and their god. And this is why our God also saw idolatry in sexual terms. When an Israelite worshipped an idol, Yahweh considered it adultery. That person was being unfaithful to Him. Infidelity and idolatry went hand in hand. This is the background to the story of Hosea. !1 To illustrate Israel’s spiritual betrayal of the true God, Yahweh had the Prophet Hosea marry a prostitute. As his wife, Gomer, was unfaithful to Hosea, Israel had ignored its vows to God and went to bed with idols. -

Hosea 8:1-14 Overview of Chapter 8: 1

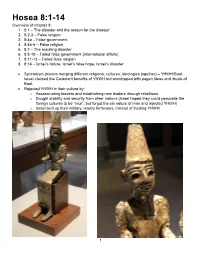

Hosea 8:1-14 Overview of chapter 8: 1. 8:1 – The disaster and the reason for the disaster 2. 8:2-3 – False religion 3. 8:4a – False government 4. 8:4b-6 – False religion 5. 8:7 – The resulting disaster 6. 8:8-10 – Failed false government (international affairs) 7. 8:11-13 – Failed false religion 8. 8:14 – Israel’s failure, Israel’s false hope, Israel’s disaster Syncretism (means merging different religions, cultures, ideologies together) – YHWH/Baal: Israel claimed the Covenant benefits of YHWH but worshipped with pagan ideas and rituals of Baal. Rejected YHWH in their culture by: o Assassinating leaders and establishing new leaders through rebellions o Sought stability and security from other nations (Israel hoped they could persuade the foreign cultures to be “nice”, but forgot the sin nature of man and rejected YHWH) o Israel built up their military, mainly fortresses, instead of trusting YHWH 1 Baal images: Baal, the god of fertility and storms. Baal was the son of El. The raised right arm is the gesture of Baal smiting. The idol would have been holding a spear or a mace, but it has perished or been lost. These were found at Megiddo which is along the south side of the Jezreel Valley. These artifacts are in the Chicago Oriental Institute Museum and were found during the 1930’s excavation. There is shown below a four horned altar and an offering stand found in the palace complex which would have held a dish for liquid, food or incense offering. 2 Ivory inlays from Megiddo that at one time were used to decorate wooden furniture, etc. -

Parashat Vayetze אציו

ויצא Parashat Vayetze Torah: Genesis 28:10–32:3 Haftarah: Hosea 12:13–14:10 The Battle Of The Wits General Overview The main character of Parashat Vayetze is Jacob. This portion begins as Jacob is busy packing his bags to flee from his angry brother, Esau, and closes with Jacob fleeing again, but this time from his angry father-in-law and uncle, Laban. During his journeys, we see Jacob caught in a cycle of deception. In this battle of wits, a younger Jacob, whose life has thus far been characterized by shrewdness, is pitted against an older more experienced conniver, Laban. Let us examine how Jacob conducts himself and what he learns during these difficult years in his life. In the process, we shall also see how God sovereignly uses all of the events in order to carry out His eternal will for Israel. Exposition The following outline represents our approach to this match of trickery: I. Preparations for the Battle: God Speaks to Jacob II. The Battle III. First Round: Laban Frustrates Jacob IV. Second Round: Jacob Out-Smarts Laban V. Third Round: Rachel Joins the Battle VI. The Aftermath of the Battle: God Speaks to Laban In this excerpt from Parashat Vayetze, we will focus on section I, Preparations for the Battle. I. Preparations for the Battle: God Speaks To Jacob In the first part of this sidra we shall examine Jacob’s famous dream. First, we shall look at some of the data, and then we shall continue by exploring some interpretations. Jacob was alone on his flight from the family home in Beer Sheba to his ancestral home in Haran. -

Basic Judaism Course Copr

ה"ב Basic Judaism Course Copr. 2009 Rabbi Noah Gradofsky Syllabus Basic Judaism Course By: Rabbi Noah Gradofsky Greetings and Overview ................................................................................................................. 3 Class Topics.................................................................................................................................... 3 Reccomended Resources ................................................................................................................ 4 Live It, Learn It............................................................................................................................... 6 On Gender Neutrality...................................................................................................................... 7 Adult Bar/Bat Mitzvah.................................................................................................................... 8 Contact Information........................................................................................................................ 8 What is Prayer?............................................................................................................................... 9 Who Is Supposed To Pray?........................................................................................................... 10 Studying Judaism With Honesty and Integrity ............................................................................. 10 Why Are Women and Men Treated Differently in the Synagogue?