ROCAILLE ORNAMENTAL AGENCY and the DISSOLUTION of SELF in the ROCOCO ENVIRONMENT Julie Boivin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building an Adu

BUILDING AN ADU GUIDE TO ACCESSORY DWELLING UNITS 1 451 S. State Street, Room 406 Salt Lake City, UT 84114 - 5480 P.O. Box 145480 CONTENT 04 OVERVIEW 08 ELIGIBILITY 11 BUILDING AN ADU Types of ADU Configurations 14 ATTACHED ADUs Existing Space Conversion // Basement Conversion // This handbook provides general Home with Attached Garage // Addition to House Exterior guidelines for property owners 21 DETACHED ADUs Detached Unit // Detached Garage Conversion // who want to add an ADU to a Attached Above Garage // Attached to Existing Garage lot that already has an existing single-family home. However, it 30 PROCESS is recommended to work with a 35 FAQ City Planner to help you answer any questions and coordinate 37 GLOSSARY your application. 39 RESOURCES ADU regulations can change, www.slc.gov/planning visit our website to ensure latest version 1.1 // 05.2020 version of the guide. 2 3 OVERVIEW WHAT IS AN ADU? An accessory dwelling unit (ADU) is a complete secondary residential unit that can be added to a single-family residential lot. ADUs can be attached to or part of the primary residence, or be detached as a WHERE ARE WE? separate building in a backyard or a garage conversion. Utah is facing a housing shortage, with more An ADU provides completely separate living space people looking for a place to live than there are homes. including a kitchen, bathroom, and its own entryway. Low unemployment and an increasing population are driving a demand for housing. Growing SLC is the City’s adopted housing plan and is aimed at reducing the gap between supply and demand. -

Door/Window Sensor DMWD1

Always Connected. Always Covered. Door/Window Sensor DMWD1 User Manual Preface As this is the full User Manual, a working knowledge of Z-Wave automation terminology and concepts will be assumed. If you are a basic user, please visit www.domeha.com for instructions. This manual will provide in-depth technical information about the Door/Window Sensor, especially in regards to its compli- ance to the Z-Wave standard (such as compatible Command Classes, Associa- tion Group capabilities, special features, and other information) that will help you maximize the utility of this product in your system. Door/Window Sensor Advanced User Manual Page 2 Preface Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................. 2 Description & Features ..................................................................................................... 4 Specifications ..................................................................................................................... 5 Physical Characteristics ................................................................................................... 6 Inclusion & Exclusion ........................................................................................................ 7 Factory Reset & Misc. Functions ..................................................................................... 8 Physical Installation ......................................................................................................... -

Movement on Stairs During Building Evacuations

NIST Technical Note 1839 Movement on Stairs During Building Evacuations Erica D. Kuligowski Richard D. Peacock Paul A. Reneke Emily Wiess Charles R. Hagwood Kristopher J. Overholt Rena P. Elkin Jason D. Averill Enrico Ronchi Bryan L. Hoskins Michael Spearpoint This publication is available free of charge from: http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1839 NIST Technical Note 1839 Movement on Stairs During Building Evacuations Erica D. Kuligowski Richard D. Peacock Paul A. Reneke Emily Wiess Kristopher J. Overholt Rena P. Elkin Jason D. Averill Fire Research Division Engineering Laboratory Charles R. Hagwood Statistical Engineering Division Information Technology Laboratory Enrico Ronchi Lund University Lund, Sweden Bryan L. Hoskins Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK Michael Spearpoint University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand This publication is available free of charge from http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1839 January 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce Penny Pritzker, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Willie May, Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology and Acting Director Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. National Institute of Standards and Technology Technical Note 1839 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Tech. Note 1839, 213 pages (January 2015) This publication is available free of charge from: http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1839 CODEN: NTNOEF Abstract The time that it takes an occupant population to reach safety when descending a stair during building evacuations is typically estimated by measureable engineering variables such as stair geometry, speed, stair density, and pre-observation delay. -

Single Family Housing Design Standards

TEXAS GENERAL LAND OFFICE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT AND REVITALIZATION HOUSING DESIGN STANDARDS (SINGLE FAMILY) Revised July 21, 2020 TEXAS GENERAL LAND OFFICE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT AND REVITALIZATION DIVISION GLO-CDR HOUSING DESIGN STANDARDS (SINGLE FAMILY) The purpose of the Texas General Land Office Community Development and Revitalization division’s (GLO-CDR) Housing Design Standards (the Standards) is to ensure that all applicants (single family housing applicants) who receive new or rehabilitated construction housing through programs funded through GLO-CDR live in housing which is safe, sanitary, and affordable. Furthermore, these Standards shall ensure that the investment of public and homeowner funds results in lengthening the term of affordability and the preservation of habitability. All work carried out with the assistance of funds provided through GLO-CDR shall be done in accordance with these Standards and the GLO-CDR Housing Construction Specifications as they apply to single family housing applicants and, unless otherwise defined, shall meet or exceed industry and trade standards. Codes, laws, ordinances, rules, regulations, or orders of any public authority in conflict with installation, inspection, and testing take precedence over these Standards. A subrecipient can request a variance for any part of these Standards for a specific project by submitting a written request to GLO-CDR detailing the project location, the need for the variance, and, if required, the proposed alternative. Variance requests can be submitted to: Martin Rivera Jerry Rahm Monitoring & QA Deputy Director Housing Quality Assurance Manager Community Development and Community Development and Revitalization Revitalization Texas General Land Office Texas General Land Office Office 512-475-5000 Office 512-475-5033 [email protected] [email protected] 1700 North Congress Avenue, Austin, Texas 78701-1495 P.O. -

Bases and Support

BASES AND SUPPORT BASES AND SUPPORT Span Between Table Legs 640 Base Requirements 641 Base Units 645 “L” Adjustable Height Bases 676 “L” Worksurfaces 684 BASES AND SUPPORT NATIONAL OFFICE FURNITURE—CASEGOODS 2 639 BASES AND SUPPORT SPAN BETWEEN TABLE LEGS For leg-based applications, the maximum recommended span 3 of an unsupported 1⁄16" thick worksurface is 48" between legs. 9 The maximum recommended span of an unsupported 1⁄16" thick worksurface is 60" between legs. Additional support is recommended for deflection for longer distances. When using mobile legs with tops that are 60" and greater, undersupport rails are recommended. RECTANGULAR WORKSURFACES RECOMMENDED SPAN BETWEEN LEGS FOR STABILITY AND VISUAL APPEARANCE 3 9 LENGTH 1⁄16" WORKSURFACE 1⁄16" WORKSURFACE C-LEG / T-LEG COLUMN LEG C-LEG / T-LEG COLUMN LEG 96" N/A N/A N/A N/A 84" N/A N/A N/A N/A 72" 48" 48" 48" 48" 66" 48" 48" 48" 48" 60" 42" 48" 42" 48" 54" 36" 46" 36" 46" 48" 30" 40" 30" 40" 42" 24" 34" 24" 34" U-SHAPED WORKSURFACE RECOMMENDED SPAN BETWEEN LEGS 3 9 LENGTH 1⁄16" WORKSURFACE 1⁄16" WORKSURFACE C-LEG / T-LEG COLUMN LEG C-LEG / T-LEG COLUMN LEG 1 1 60" 40" 40⁄16" 40" 40⁄16" 3 1 3 1 48" 28⁄16" 28⁄8" 28⁄16" 28⁄8" See table/base matrix for specific base options (pages 641-644) For leg-based training applications, use Undersurface Support Rail for extra support and deflection on 60", 66" and 72" worksurfaces. -

Bilco Floor, Vault and Sidewalk Doors Provide Reliable Access to Equipment Stored Underground Or Below/Between Building Floors

Floor & Vault Doors Bilco Floor, Vault and Sidewalk Doors provide reliable access to equipment stored underground or below/between building floors. Commonly used by gas, electric and water utilities for frequent access by service personnel, Bilco doors are available in many different sizes and configurations to suit any application. Floor & Vault Doors Advantages of Floor, Vault and Sidewalk Doors Bilco Floor, Vault and Sidewalk Doors are ruggedly constructed to provide many years of dependable service. Doors are available in a wide range of sizes and configurations, and all models offer the following standard features and benefits: • Engineered lift assistance for smooth, easy door operation, regardless of cover size and weight • Automatic holdopen arm that locks the cover in the open position to ensure safe egress • Type 316 stainless steel slam lock to prevent unauthorized access • Constructed with corrosion resistant materials and hardware • Heavy duty hinges, custom engineered for horizontal door applications Positive latching mechanism Structurally reinforced cover with finished edges Heavy-duty hinges Automatic hold-open arm with convenient release handle Lift assistance counterbalances cover Type J-AL door shown Typical Applications • Airports • Manufacturing Facilities • Schools • Correctional Facilities • Natural Gas Utilities •Telecommunications Vaults • Electric Utilities • Office Buildings •Transit Systems • Factories • Processing Plants •Warehouses • Hospitals • Retail Structures •Water/Waste Treatment Plants Drainage Doors Type J Steel Type J Type J-AL Aluminum With Drainage Channel Frame For use in exterior applications where there is concern about water or other liquids entering the access opening. Type J H20 Steel Type J H20 Type J-AL H20 Aluminum With Drainage Channel Frame For use in exterior applications where the doors will be subjected to vehicular traffic. -

WINDOWS and DOORS Windows and Doors Are Necessary Features of All Residential Structures and Should Be Planned Carefully to Insu

WINDOWS AND DOORS Windows and doors are necessary features of all residential structures and should be planned carefully to insure maximum contribution to the overall design and function of a structure. Windows and doors perform several functions in a residential structure, such as: shield an opening from the elements, add decoration, emphasize the overall design, provide light and ventilation, and expand visibility. DOORS Each door identified on the foundation plan and floor plan should appear on a door schedule. Specifications vary amongst manufacturer, so it is important to have exact information for the schedule. Interior Doors Interior door types include; flush, panel, bi-fold, sliding, pocket, double-action, accordion, Dutch, and French. Flush Doors • Smooth on both sides, usually made of wood and are hollow on the inside with a wood frame around the perimeter • Standard size is 1-3/8” thick, 6’8” high and range from 2’ – 3’ wide Panel Doors Most Common Door • Panel doors have a heavy frame around the outside and generally have cross members that form small panels • The vertical members are called stiles • The horizontal pieces are called rails Bi-Fold Doors • A bi-fold door is made of two parts that together form the door • Popular as closet doors and are seldom used for other applications • Installed in pairs with each door being the same width, which ranges from 1’ – 2’ • Standard height 6’8” – 8’ • Thickness of 1-1/8” for wood doors and 1” for metal Sliding Doors • Sliding or bi-pass doors are popular where there are large openings -

Windows to the World - Doors to Space - a Reflection on the Psychology and Anthropology of Space Architecture

Space: Science, Technology and the Arts (7th Workshop on Space and the Arts) 18-21 May 2004, ESA/ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands Windows to the world - Doors to Space - a reflection on the psychology and anthropology of space architecture. Andreas Vogler, Architect(1), Jesper Jørgensen, Psychologist(2) (1)Architecture and Vision / SpaceArch Hohenstaufenstrasse 10, D-80801 MUNICH GERMANY [email protected], [email protected] (2) SpaceArch c/o Kristian von Bengtson Prinsessegade 7A, st.tv DK - 1422 Copenhagen K, Denmark [email protected] ABSTRACT Living in a confined environment as a space habitat is a strain on normal human life. Astronauts have to adapt to an environment characterized by restricted sensory stimulation and the lack of “key points” in normal human life: seasons, weather change, smell of nature, visual, audible and other normal sensory inputs which give us a fixation in time and place. Living in a confined environment with minimal external stimuli available, gives a strong pressure on group and individuals, leading to commonly experienced symptoms: tendency to depression, irritability and social tensions. It is known, that perception adapts to the environment. A person living in an environment with restricted sensory stimulation will adapt to this situation by giving more unconscious and conscious attention to the present sensory stimuli. Newest neurobiological research (neuroaestetics) shows that visual representations (like Art) have a remarkable impact in the brain, giving knowledge that these representations both function as usual information and as information on a higher symbolic level (Zeki). Therefore designing a space habitat must take into consideration the importance of design, not only in its functional role, but also as a combination of functionality, mental representation and its symbolic meaning, seen as a function of its anthropological meaning. -

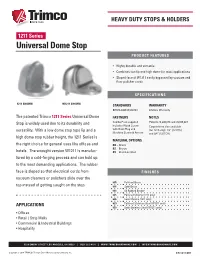

1211 Series Universal Dome Stop PRODUCT FEATURES

HEAVY DUTY STOPS & HOLDERS 1211 Series Universal Dome Stop PRODUCT FEATURES • Highly durable and versatile • Combines low lip and high dome for most applications • Sloped face of W1211 easily bypassed by vacuum and floor polisher cords SPECIFICATIONS 1211 SHOWN W1211 SHOWN STANDARDS WARRANTY BHMA L02141/L02161 Lifetime Warranty The patented Trimco 1211 Series Universal Dome FASTNERS NOTES Stop is widely used due to its durability and Combo Pack supplied Patents #4,209,876 and #6,035,487 includes Wood Screw Carpet risers also available versatility. With a low dome stop type lip and a with Rawl Plug and (for 1211 only): 1/2” (1211CL) Machine Screw & Anchor and 3/4” (1211CH) high dome stop rubber height, the 1211 Series is MATERIAL OPTIONS the right choice for general uses like offices and BR – Brass BZ – Bronze hotels. The wrought version W1211 is manufac- SS – Stainless Steel tured by a cold-forging process and can hold up to the most demanding applications. The rubber face is sloped so that electrical cords from FINISHES vacuum cleaners or polishers slide over the 605 Polished Brass top instead of getting caught on the stop. 606 Satin Brass 613 Oil Rubbed Bronze 625 Polished Chrome (1211 only) 626 Satin Chrome (1211 only) APPLICATIONS 629 Polished Stainless Steel (W1211 only) 630 Satin Stainless Steel (W1211 only) • Offices • Retail / Strip Malls • Commercial & Industrial Buildings • Hospitality 3528 EMERY STREET LOS ANGELES, CA 90023 | (323) 262-4191 | WWW.TRIMCOHARDWARE.COM | [email protected] Copyright © 2014 TRIMCO, Triangle Brass Manufacturing Company, Inc. CS-1211-001 HEAVY DUTY STOPS & HOLDERS 1211 Series Universal Dome Stop HOW TO SPECIFY & ORDER CHOOSE THE FOLLOWING SERIES FINISHES • 1211 Cast Universal Door Stop • 625 Polished Chrome (1211 only) • W1211 Wrought Universal Door Stop • 626 Satin Chrome (1211 only) • 629 Polished Stainless Steel (W1211 only) • 630 Satin Stainless Steel (W1211 only) See Finish List for all options. -

Destroyers Builders

studio destroyers builders INTRODUCING THE COLLECTION Inspired by architectural shapes that are foremost functional and all have an elementary character, the collection highlights the field between human and industrial through diverse materials. Exploring architectural and sculptural details and focussing on the beauty in diverse materials. The touchabilty of the surface and the human traces that are still visible in the objects, explain the method of Destroyers/Builders. Both contemporary and classical fragments are the base of the visual language of the furniture pieces. The Bolder Chair and Bolder Seat are inspired by columns. The layering of the chipboard discs refers to columns of stone that are also built up of layers. Cross Vault is a down scaled cross vault built in aluminium, functioning as a low seating element. Bolder Seat is an even more softer reference to columns and elemental shapes. It is a diverse set of furniture, between sculptural and architectural forms. Destroyers/Builders is a Brussels based design studio. With a focus on materiality the studio strives for sensory relevance and cultural value in detail and bigger scale. The works have a sculptural and architectural character, but are always on the edge of contemporary material use and traditional crafts. The studio takes on projects that range from commissions to self-initiated projects, and extends across the realms of both product and interior design. For enquiries on one of the works, the email address below can be used. Linde Freya Tangelder [email protected] www.destroyersbuilders.com +32 494 908946 BOLDER SEAT The soft stool is a continuation of the column based shapes. -

Tour Booklet (PDF)

Tour Booklet WNB FINANCIAL MORE THAN A BANK Exploring our Historic Downtown treasured heritage. Office Tour 204 Main Street General Information: 507-454-8800 Toll Free: 1-800-546-4392 Museum Hours: Monday – Friday, 8:30 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. www.WNBFinancial.com Follow us on: Explore our treasured heritage. INANCIAL WNMOREB T FHAN A BANK 8/18 Tiffany Studios created the center ceiling cove from George Maher sketches. The Prairie design style appears in the ceilings of the upper level meeting rooms. The stepped design echoes the patterns in the furniture that was custom built for those rooms. Furniture Decorative cove (above) The chairs and and Prairie style molding. Welcome tables both reflect Thank you for touring the Prairie School influences. These original furniture Downtown office of pieces were carefully restored in 1991 during the WNB Financial. building’s last major renovation. You will find many interesting Thank You! artistic and architectural We hope you enjoyed your tour of WNB features on the tour. Financial’s Downtown We hope you enjoy your visit! building. If you would like to arrange a group tour, please call at least one day in advance (507-454-8800 or 1-800-546-4392 if calling from outside the Winona area). WNB Financial gratefully acknowledges the Winona County Historical Society for the use of its resources Prairie School-inspired The completed building in 1916. in the publication of furniture. this book. 2 11 Staircases A Brief History of the Bank The white marble’s The bank was formed as the Winona Savings strength and Bank and began business in July 1874. -

Safety on Stairs

d Div. 100 ! i I 1 ' L BS BUILDING SCIENCE SERIES 108 afety on Stairs S DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE • NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote pubUc safety. The Bureau's technical work is performed by the National Measurement Laboratory, the National Engineering Laboratory, and the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology. THE NATIONAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY provides the national system of physical and chemical and materials measurement; coordinates the system with measurement systems of other nations and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical and chemical measurement throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce; conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government Agencies; develops, produces, and distributes Standard Reference Materials; and provides calibration services.