April 2021 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ing Items Have Been Registered

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 37 June 2017 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Alrekr Bergsson. Device. Per saltire gules and sable, in pale two wolf’s heads erased and in fess two sheaves of arrows Or. Brahen Lapidario. Name and device. Argent, a lozenge gules between six French-cut gemstones in profile, two, two and two azure, a base gules. The ’French-cut’ is a variant form of the table cut, a precursor to the modern brilliant cut. It dates to the early 15th Century, according to "Diamond Cuts in Historic Jewelry" by Herbert Tillander. There is a step from period practice for gemstones depicted in profile. Hrólfr á Fjárfelli. Device. Argent estencely sable, an ash tree proper issuant from a mountain sable. Isabel Johnston. Device. Per saltire sable and purpure, a saltire argent and overall a winged spur leathered Or. Lisabetta Rossi. Name and device. Per fess vert and chevronelly vert and Or, on a fess Or three apples gules, in chief a bee Or. Nice early 15th century Florentine name! Símon á Fjárfelli. Device. Azure, a drakkar argent and a mountain Or, a chief argent. AN TIR Akornebir, Canton of. Badge for Populace. (Fieldless) A squirrel gules maintaining a stringless hunting horn argent garnished Or. An Tir, Kingdom of. Order name Order of Lions Mane. Submitted as Order of the Lion’s Mane, we found no evidence for a lion’s mane as an independent heraldic charge. We therefore changed the name to Order of _ Lions Mane to follow the pattern of Saint’s Name + Object of Veneration. -

Talking Gothic! What Do We Mean by Gothic Architecture and How Can We Identify It?

Talking Gothic! What do we mean by Gothic architecture and how can we identify it? ‘Gothic’ is the name we give to a style of architecture from the Middle Ages. It is usually thought to have begun near Paris in the middle of the 1100s and, from there, it spread throughout Europe and continued into the 16th century. There are many marvellous examples of Gothic buildings throughout Scotland: from Elgin Cathedral in Moray, through amazing buildings like Glasgow Cathedral, Paisley Abbey and Edinburgh St Giles, down to Melrose Abbey in the Scottish Borders. All of these, and more, are well worth a visit! Gothic architecture developed from an earlier style we call Romanesque. Buildings made in the Romanesque style often have rounded arches on their (usually comparatively small) windows and doors, thick columns and walls, lots of ornamental patterns, and shorter structures than the buildings which came later. Dunfermline Abbey is a great example of a Romanesque building in Scotland. The people who paid for the earliest Gothic buildings expressed a wish to transport worshippers to a kind of Heaven on Earth by building higher and brighter churches. What emerged is what we now describe as Gothic. Fashions changed throughout the time that Gothic was the predominant style, and it also varied from place to place. However, the Classical revival made popular as part of the Italian Renaissance largely replaced the Gothic style, and it wasn’t fashionable again until the 19th century. During the Romantic Movement Medieval literature, arts and crafts enjoyed renewed popularity. As a result, Glasgow Cathedral was begun in the Gothic elements can be seen today in the churches, public buildings, and late 12th century and was at the hub of the Medieval city. -

North Queensferry and Inverkeithing (Potentially Vulnerable Area 10/10)

North Queensferry and Inverkeithing (Potentially Vulnerable Area 10/10) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Forth Estuary Fife Council South Fife coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impacts flooding of Summary At risk of flooding • 40 residential properties • 30 non-residential properties • £590,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning -

Why Is It Called Easter?

March 20, 2018 Why Is It Called Easter? Easter is the name of the most important Christian holiday, the day we celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead after his crucifixion. The resurrection of Jesus resides at the very heart of the gospel: “For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures” (1 Cor. 15:3-4). But, why is this holiday called Easter? Where did the name Easter come from? Let’s shed some light on those questions. Easter is an English word The etymology of the English word Easter indicates that it descends from the Old German—likely from root words for dawn, east, and sunrise. English is a western Germanic language named for the Angles who, along with the Saxons (another Germanic tribe), settled Britain in the 5th century. In fact, the Old German for Easter was Oster (Ostern in the modern). English and German speakers have been using variations of the term Easter for over a millennium. However, most of the countries surrounding Britain and the German principalities of Europe have long used variants of the Latin Pascha (from the Greek for Passover, a transliteration of the Hebrew pesach) as the name of the celebration of Christ’s resurrection. Today, in many non-English speaking countries, Easter is still called by a name derived from the term Pashca. A number of other languages use a term that means Resurrection Feast or Great Day. -

News Release

Press Office Threadneedle Street London EC2R 8AH T 020 7601 4411 F 020 7601 5460 [email protected] www.bankofengland.co.uk 17 June 2009 Dunfermline Resolution: Announcement of the Preferred Bidder for the Social Housing Lending Business The Bank of England has selected Nationwide Building Society as the preferred bidder for the social housing loans and related deposits from housing associations (the 'Business') held by the Bank of England's wholly- owned subsidiary, DBS Bridge Bank Limited. This follows a competitive auction process conducted by the Bank of England, in accordance with the Code of Practice issued by HM Treasury under the Banking Act 2009. The Business had previously been transferred from Dunfermline Building Society ('Dunfermline') to DBS Bridge Bank Limited while a permanent home for the Business was sought. The transfer of the Business to the bridge bank took place on 30 March 2009 at the same time as the sale of certain core parts of Dunfermline to Nationwide Building Society. Dunfermline was then placed into the Building Society Special Administration Procedure. It is business as usual for the Business's customers. They can contact the Business in the usual way and should continue to make repayments as normal. Customers of other parts of the former Dunfermline Building Society's businesses now owned by Nationwide, or operated out of the Building Society Special Administration Procedure, are unaffected. The decision to select Nationwide Building Society as the preferred bidder followed advice from the Bank of England's Financial Stability Committee and consultation with the FSA and HM Treasury in accordance with the Banking Act 2009. -

Perth & Kinross Council Archive

Perth & Kinross Council Archive Collections Business and Industry MS5 PD Malloch, Perth, 1883-1937 Accounting records, including cash books, balance sheets and invoices,1897- 1937; records concerning fishings, managed or owned by PD Malloch in Perthshire, including agreements, plans, 1902-1930; items relating to the maintenance and management of the estate of Bertha, 1902-1912; letters to PD Malloch relating to various aspects of business including the Perthshire Fishing Club, 1883-1910; business correspondence, 1902-1930 MS6 David Gorrie & Son, boilermakers and coppersmiths, Perth, 1894-1955 Catalogues, instruction manuals and advertising material for David Gorrie and other related firms, 1903-1954; correspondence, specifications, estimates and related materials concerning work carried out by the firm, 1893-1954; accounting vouchers, 1914-1952; photographic prints and glass plate negatives showing machinery and plant made by David Gorrie & Son including some interiors of laundries, late 19th to mid 20th century; plans and engineering drawings relating to equipment to be installed by the firm, 1892- 1928 MS7 William and William Wilson, merchants, Perth and Methven, 1754-1785 Bills, accounts, letters, agreements and other legal papers concerning the affairs of William Wilson, senior and William Wilson, junior MS8 Perth Theatre, 1900-1990 Records of Perth Theatre before the ownership of Marjorie Dence, includes scrapbooks and a few posters and programmes. Records from 1935 onwards include administrative and production records including -

The Integration of Mythical Creatures in the Harry Potter Series

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 orange eyes. (Stone 235) Harry's first year introduces the The Integration of Mythical traditional serpentine dragon, something that readers Creatures in the Harry Potter can envision with confidence and clarity. The fourth year, however, provides a vivid insight on the break Series from tradition as Harry watches while “four fully grown, Terri Pinyerd enormous, vicious-looking dragons were rearing onto English 200D their hind legs inside an enclosure fenced with thick Fall 2014 planks of wood, roaring and snorting—torrents of fire were shooting into the dark sky from their open, fanged From the naturalistic expeditions of Pliny the mouths, fifty feet above the ground on their outstretched Elder, to the hobbit's journey across Middle Earth, necks” (Goblet 326). This is a change from the treasure the literary world has been immersed in the alluring hoarding, princess stealing, riddle loving dragons of presence of mythical and fabulous creatures. Ranging fantasy and fairy tales; these are beasts that can merely from the familiar winged dragon to the more unusual be restrained, not tamed. It is with this that Rowling and obscure barometz, the mythical creature brings with sets the feel for her series. The reader is told that not it a sense of imagined history that allows the reader to everything is as it seems, or is expected to be. Danger is become immersed in its world; J.K Rowling's best-selling real, even for wizards. Harry Potter series is one of these worlds. This paper will If the dragon is the embodiment of evil and analyze the presence of classic mythical creatures in the greed, the unicorn is its counterpart as the symbol of Harry Potter series, along with the addition of original innocence and purity. -

Sizzle and Drizzle Handy Index

INDEX A Cake, Yorkshire Teacakes, 103 A Letter from Nancy, 1 Cakes, Intro, 106 Acknowledgements, 414 Cakes, Recipes, 114 Almond Sponge, 340 Caramel, 346 Apple & Cinnamon Scones, 56 Caramel, Cracking (Creme Brûlée), 351 Apple Charlotte, 305 Carrot & Orange Cake, 151 Arctic Bundt, 364 Cheat’s Almond Tarts, 255 Cheese and Onion Flan, 224 B Cheese Scones, 58 Baby Biscotti, 44 Chelsea Buns, 82 Barbados Banana Bread, 118 Cherry Almond Traybake, 120 Biscotti, Baby, 44 Cherry Bakewell Scones, 53 Biscuits, Intro, 27 Cherry Chocolate Roulade, 131 Biscuits, Lemon Shortbread, 29 Chicken and Tarragon Pie, 218 Biscuits, Recipes, 29 Choco-Fudge Slices, Low Sugar, 193 Biscuits, Vanilla Shortbread, 34 Chocolate Recipes, 114, 131, 158, 160, 193, 237, Blackberry Pie, 234 256, 265, 338, 343 Brandy Snaps, 38 Chocolate & Amaretto Festive Cupcakes, 158 Bread & Butter Pudding, 295 Chocolate and Orange Delice, 343 Bread, Barbados Banana, 118 Chocolate Crusted Passion Fruit Tart, 256 Bread, Intro, 61 Chocolate for Profiteroles, 265 Bread, No Knead, 94 Chocolate Fudge Cake, 114 Bread, Recipes, 70 Chocolate Paste, 265 Bread, Soft White, 70 Chocolate Swiss Meringue Buttercream, 175 Bread, Sourdough, 89 Chocolate, Vanilla & Strawberry Drip Cake, 160 Brioche, 98 Choux Pastry, 265 Buttercream, 169 Christmas , 32, 135, 158, 298, 311 Buttercream, Chocolate Swiss Meringue, 175 Christmas Cake, 133 Buttercream, Coffee, Filling, 170 Chutney, End of Season, 382 Buttercream, Italian Meringue, 171 Citrus Passet with Blueberries, 354 Buttercream, Not Too Sweet, 156 Clean a Decanter -

The Magazine of the Launceston Area Methodist Church April 2021 Edition 207

The Magazine of the Launceston Area Methodist Church April 2021 Edition 207 1 Dear Friends It is a great privilege to be asked to write an Easter message this year to you. We have all had a difficult year because of COVID 19 and I believe that the last three months have been especially difficult. The long days of restrictions have been hard for all of us and we have all probably wondered when they will come to an end so that life can go back to normal. I find it a great comfort to go out on walks with my dog Sam. Sam’s favourite place to go is wherever there are woodlands and if there’s a river as well that’s even better! He loves to chase after sticks and if they go in the water he loves to swim after them. Frank and I get a great deal of pleasure from watching Sam but we also enjoy hearing the birds singing, the golden heads of the daffodils, the snowdrops, the primroses and the trees bursting into blossom; all these things are signs of new life and the promise that warmer weather is on the way. The message of Easter is all about new life, love and hope. It is about the true story of God’s love and forgiveness of sins shown to us through the death of Jesus, His Son; it is also a celebration that God raised Jesus to new life so that our joy may be complete as we trust in Him and follow in His ways. -

Make Your Own Lion and Unicorn Puppets

Scotland’s historic properties feature lots of lions and unicorns – they’re in Scotland’s royal coat of arms. Lions were thought to represent bravery and strength – the king of the animal world. The unicorn has been a Scottish royal symbol for around 600 years and – believe it or not – is Scotland’s national animal. Unicorns symbolised innocence and power. People considered them wild and untamed, so they’re often shown chained around their neck. When James VI of Scotland unified Scotland and England in 1603, he changed his coat of arms to include one unicorn and one lion either side of a shield. TOP TIPS FOR MAKING YOUR PUPPETS This activity ideally needs a printer and some brass paper fasteners. If you don’t have a printer, why not use the templates as inspiration for drawing your own versions! And if you don’t have paper fasteners (split pins), you could experiment with tying a big knot in some string or wool, threading the string through a small hole in your papers (a hole punch would create too big a hole) and tying another big knot on the other side. If you’ve got beads or buttons you could also use these to secure the wire/string/wool either side of the paper body parts you’re attaching together. The lion that greets The unicorn from visitors arriving at the King’s Fountain Edinburgh Castle. at Linlithgow Palace. Resource created for Historic Environment Scotland by artist Hannah Ayre. 1. Print out the template onto 2. Cut out the shapes card or print onto paper, then glue onto card such as a cereal box, then colour in the shapes. -

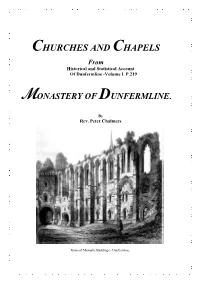

Churches and Chapels Monastery

CHURCHES AND CHAPELS From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline -Volume I. P.219 MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE. By Rev. Peter Chalmers Ruins of Monastic Buildings - Dunfermline. A REPRINT ON DISC 2013 ISBN 978-1-909634-03-9 CHURCHES AND CHAPELS OF THE MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE FROM Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline Volume I. P.219 By Rev. Peter Chalmers, A.M. Minister of the First Charge, Abbey Church DUNFERMLINE. William Blackwood and Sons Edinburgh MDCCCXLIV Pitcairn Publications. The Genealogy Clinic, 18 Chalmers Street, Dunfermline KY12 8DF Tel: 01383 739344 Email enquiries @pitcairnresearh.com 2 CHURCHES AND CHAPELS OF THE MONASTERY OF DUNFERMLINE. From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline Volume I. P.219 By Rev. Peter Chalmers The following is an Alphabetical List of all the Churches and Chapels, the patronage which belonged to the Monastery of Dunfermline, along, generally, with a right to the teinds and lands pertaining to them. The names of the donors, too, and the dates of the donation, are given, so far as these can be ascertained. Exact accuracy, however, as to these is unattainable, as the fact of the donation is often mentioned, only in a charter of confirmation, and there left quite general: - No. Names of Churches and Chapels. Donors. Dates. 1. Abercrombie (Crombie) King Malcolm IV 1153-1163. Chapel, Torryburn, Fife 11. Abercrombie Church Malcolm, 7th Earl of Fife. 1203-1214. 111 . Bendachin (Bendothy) …………………………. Before 1219. Perthshire……………. …………………………. IV. Calder (Kaledour) Edin- Duncan 5th Earl of Fife burghshire ……… and Ela, his Countess ……..1154. V. Carnbee, Fife ……….. ………………………… ……...1561 VI. Cleish Church or……. Malcolm 7th Earl of Fife. -

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson Introduction Sociologist Bryan R. Wilson once alleged that post-modern technology and secularisation are the allied forces of rationality and disenchantment that pose an immense threat to traditional religion.1 However, the flexibility of pastiche Neopagan belief systems like ‘Witchcraft’ have creativity, fantasy, and innovation at their core, allowing practitioners of Witchcraft to respond in a unique way to the post-modern age by integrating technology into their perception of the sacred. The phrase Deus ex Machina, the God out of the Machine, has gained a multiplicity of meanings in this context. For progressive Witches, the machine can both possess its own numen and act as a conduit for the spirit of the deities. It can also assist the practitioner in becoming one with the divine by enabling a transcendent and enlightening spiritual experience. Finally, in the theatrical sense, it could be argued that the concept of a magical machine is in fact the contrived dénouement that saves the seemingly despondent situation of a so-called ‘nature religion’ like Witchcraft in the techno-centric age. This paper explores the ways two movements within Witchcraft, ‘Technopaganism’ and ‘Technomysticism’, have incorporated man-made inventions into their spiritual practice. A study of how this is related to the worldview, operation of magic, social aspect and development of self within Witchcraft, uncovers some of the issues of longevity and profundity that this religion will face in the future. Witchcraft as a Religion The categorical heading ‘Neopagan’ functions as an umbrella that covers numerous reconstructed, revived, or invented religious movements, that have taken inspiration from indigenous, archaic, and esoteric traditions.