Report on the Manitoba Economy: 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manitoba's Top Employers

TOP EMPLOYERS COMPETITION ABOUT MORE THAN JUST NUMBERS BY GEOFF KIRBYSON Your dream employer might be Google or Facebook, but the researchers behind the Manitoba’s Top Employers project hope job-seekers will wake up to what really makes a company a great place to work. As part of the Toronto-based Canada’s Top 100 Employers competition, the research team aims to increase the literacy of the national workforce, particularly millennials who tend to get caught up in the hype surrounding high-profile companies. Likes, views and retweets are fine in the moment, but they’re worth nothing when it comes to your future, they say. “We still write about great employers with defined benefit pension plans,” says Tony Meehan, Publisher at Mediacorp Canada Inc., which manages the Canada’s Top 100 Employers project. “People don’t realize that can be the difference between a happy retirement or no retirement at all. As you get older, vacation time makes a big difference (in where you want to work). We still see employers offering two weeks to start and three weeks after five years. We like to publish what the MANITOBA’S very best are doing,” he says. Mediacorp has been ranking Canadian employers of all kinds for 19 years and Meehan’s team of editors doesn’t get tired of scouring the country looking for employers with interesting TOP EMPLOYERS stories of doing things differently in their industry WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 28, 2018 or region. “Each year, employers bare their souls to us. We have 400 data points that each of them shares with us, including benefits like maternity leave, top vacation allowance, training and a host of other factors,” he says. -

Order No. 176/19 MANITOBA PUBLIC INSURANCE CORPORATION (MPI

Order No. 176/19 MANITOBA PUBLIC INSURANCE CORPORATION (MPI OR THE CORPORATION): COMPULSORY 2020/2021 DRIVER AND VEHICLE INSURANCE PREMIUMS AND OTHER MATTERS December 3, 2019 BEFORE: Irene A. Hamilton, Q.C., Panel Chair Robert Gabor, Q.C., Board Chair Carol Hainsworth, Member 2329663\1\28759.38 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................. 6 1. THE RATE APPLICATION ..................................................................................... 17 1.1. Procedural History ............................................................................................... 17 1.2. The Application .................................................................................................... 19 2. PROGRAM REVENUE .......................................................................................... 22 2.1. Basic Revenue Requirement ............................................................................... 22 2.2. Vehicle Premiums ............................................................................................... 23 2.3. Driver Premiums .................................................................................................. 24 2.4. Investment Income .............................................................................................. 25 2.5. Service Fees and Other Revenues ..................................................................... 26 2.6. Extension Operations ......................................................................................... -

Electric Transit Bus in Manitoba

Zero Emission Electric Transit Bus in Manitoba Prototype Electric Transit Bus Development and Demonstration Final Report Research Partnerships & Innovation Red River College Winnipeg, Manitoba June 2017 Ray Hoemsen Executive Director Research Partnerships & Innovation Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Project Background ................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Electrified Public Transit ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 2.2 Project Genesis ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 3.0 Formulation, Objectives and Timelines............................................................................................................................................... 2 3.1 Project Formulation ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

The Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board

The Manitoba Hydro-Electric Board QUARTERLY REPORT for the three months ended June 30, 2012 Comments by THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD and by THE PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Financial Overview Manitoba Hydro incurred a net loss on consolidated electricity and natural gas operations of $24 million for the first three months of the 2012-13 fiscal year compared to net income of $6 million for the same period last year. The net loss was comprised of a $14 million loss in the electricity sector and a $10 million loss in the natural gas sector. The loss in the electricity sector was attributable to decreased revenues from extraprovincial electricity sales and higher operating expenses related to accounting changes and pension-related cost increases. The reduced electricity sector revenues and higher costs were consistent with expectations for the first quarter. The loss in the natural gas sector is the result of seasonal variations in the demand for natural gas and should be recouped over the winter heating season. Manitoba Hydro continues to experience low export market prices as a result of low natural gas prices and lower demand for electricity due to economic conditions in the U.S. Low export prices are projected to result in continuing downward pressure on net income in 2012- 13. Based on current water flow and export market conditions, Manitoba Hydro is forecasting that financial results will improve somewhat and net income should reach approximately $30 million by March 31, 2013. The achievement of this level of net income, however, is dependent on the approval of rate increase applications currently before the Public Utilities Board. -

Review of Manitoba Hydro's General Rate Application on Behalf of The

Review of Manitoba Hydro’s general rate application on behalf of the small and medium general service customer classes and Keystone Agricultural Producers prepared for Hill Sokalski Walsh Olson LLP October 31st, 2017 The potential for rate increases of nearly 50% over a five-year period will have a significant negative impact on the general service small (“GSS”) and general service medium (“GSM”) customer classes in Manitoba. Upon review of Manitoba Hydro’s general rate application, responses to information requests and minimum filing requirements, London Economics International LLC (“LEI”) finds that the proposed rate increase should be held in abeyance until (i) comprehensive macroeconomic modeling is performed; (ii) a robust independent analysis of whether Keeyask should be postponed, modified, or cancelled is submitted; and (iii) an additional independent review of Manitoba Hydro costs, staffing, and operating procedures is developed. Table of contents 1 KEY FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................................ 5 2 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 MANITOBA HYDRO’S REQUESTED RATE INCREASE ....................................................................................... 6 2.2 APPLICATION DESCRIPTION AND SCOPE ....................................................................................................... -

Manitoba Public Accounts, 1994-95. Vol. 2 Supplementary Information

DDV CA2MA TR P71 public accounts Carleton University Documents Division 1994-95 ocr 18 1995 FOR REFERENCE ONLY volume 2 — supplementary information Manitoba Finance for the year ended March 31, 1995 VOLUME 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION. 3 AUDITOR’S REPORT. 5 SALARIES AND WAGES PAID TO EMPLOYEES. 9 PAYMENTS TO CORPORATIONS, FIRMS, INDIVIDUALS, OTHER GOVERNMENTS AND GOVERNMENT AGENCIES. 93 Carleton Unsvs'siiy j Documents Division \ OCT 18 1995 for reference only STATEMENT OF PAYMENTS IN EXCESS OF $5,000 TO CORPORATIONS, FIRMS, INDIVIDUALS, OTHER GOVERNMENTS AND GOVERNMENT AGENCIES For the fiscal year ended March 31,1995 " ' ■ V PAYMENTS TO CORPORATIONS, ETC 1994-95 93 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ASH MANAGEMENT GROUP INC $7,140; ADAM A R, MORRIS $20,161; JUNIPER EMBLEMS LTD, LACOMBE AB DAUPHIN $22,759; ADVANCE PROFESSIONAL ELECTRONICS $6330; KORTEX COMPUTER CENTRE $55,645; KOVNATS ABE $6,810; ARTHUR ANDERSEN & CO $15,604; ASHTON STEVE $14,085; KOWALSKI GARY $29,169; KWIK KOPY PRINTING $61,781; ASSEMBLEE INTERNATIONALE DES $8,769; LAMOUREUX KEVIN $29,429; LATHLIN OSCAR $49384; PARLEMENTAIRES, PARIS FRANCE $6,340; BAIZLEY DR LAURENDEAU MARCEL $29,401; LEECH PRINTING LTD, OBIE $6341; BANMAN BOB, STEINBACH $20337; BARKMAN BRANDON $5328; LOVATT JAMES, EDMONTON AB $7392; AGNES, STEINBACH $6309; BARRETT BECKY $29,240; LYON STERLING R $29,914; MACKINTOSH GORD $29365; BARROW HAZEL E, CREIGHTON SK $9,526; BILTON MACKLING ALVIN, DUGALD $18325; MALINOWSKI FATHER MILDRED M, OTTAWA ON $11,624; BISON CUSTOMIZED DON, NEWMARKET ON $22588; MALOWAY JIM $27,428; -

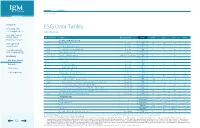

ESG Data Tables

APPENDIX OVERVIEW BUILDING AND ESG Data Tables SUSTAINING TRUST Governance HELPING CLIENTS REACH THEIR GRI Standard Topic Measurement 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 FINANCIAL GOALS BOARD COMPOSITION (a) EMPOWERING 102-22 Board Directors Number 15 15 16 16 15 OUR PEOPLE 102-22 Executive Board Members Number 1 1 1 1 2 102-22 Non-Executive Board Members Number 14 14 15 15 13 STRENGTHENING OUR COMMUNITIES 102-22 Women Directors (b) Number 5 5 4 3 1 102-22, 405-1 Board Gender Diversity Percent of total board 33 33 25 19 7 APPENDIX Board Age Diversity (b) ESG Data Tables 405-1 Over 70 Number 1 1 1 3 2 GRI Index 405-1 Between 50 and 70 Number 13 11 13 13 13 405-1 Between 30 and 49 Number 1 3 2 0 0 SASB Index 102-22 Board Tenure (b) Average Years 10 9 8 10 11 TCFD reporting 102-22 Independent Board Members (c) Number 9 9 8 8 7 102-22 Board Independence Percentage 60 60 50 50 47 102-22 Audit Committee Independence Percentage 100 100 100 100 100 102-22 Related Party and Conduct Review Committee Independence Percentage 100 100 100 100 100 102-22 Human Resources Committee Independence Percentage 50 50 20 33 50 102-22 Governance and Nominating Committee Independence Percentage 50 50 25 25 25 Average Board and Committee Meeting Attendance Rate (b) Percentage 93 94 90 95 94 102-22 Directors with 4 or less mandates (d) Percentage 100 100 100 100 100 AUDITOR’S FEES Audit fees $ 2,746,000 2,562,000 2,616,000 2,263,000 2,286,000 Audit-related fees $ 244,000 376,000 311,000 127,000 123,000 Tax fees $ 74,000 64,000 149,000 128,000 58,000 All other fees $ 314,000 281,000 629,000 424,000 310,000 Fees paid for services other than the audit Percentage 11 11 21 19 13 (a) All Board Composition data is as of the dates of the annual meetings in the respective years, except for the Average Board and Committee Meeting Attendance Rates which are as of December 31. -

Transportation Manufacturing

Transportation manufacturing Manitoba has a strong reputation for producing well-designed, high valued and engineer-driven products for Why Winnipeg? customers around the world. Our transportation manufacturing sector is driven by industry leading producers of buses, R&D hotspot coaches and firetrucks. This sector helps fuel our stable, diversified economy with ample opportunities for companies More than $100 million invested in 1 to innovate and grow. research and development in 2017 Affordable energy Academic ecosystem Winnipeg offers renewable energy that is among the lowest published electricity Red River College rates in North America2 Vehicle Technology and Research Centre This 60,000 square-foot complex combines classroom teaching Strong sales and hands on experience that replicates a typical work Manitoban companies earned nearly environment in the vehicle manufacturing industry. $3 billion in revenue for transportation equipment manufacturing in 20173 MotiveLab™ A 7,000 square-foot research facility that conducts all-weather testing on heavy vehicles. Manufacturers can test performance Central location of alternative fuels, emission reductions and new materials. North America’s geographic centre with Smart Factory the continent’s largest trimodal inland A $10-million additional investment to the Skilled Trades and port4 Technology Centre, this factory helps prepare students for innovative work with access to state-of-the-art equipment to support applied research and experiential learning. “Both New Flyer and Motor Coach are developing electric buses and exploring autonomous technology here in Winnipeg, and I cannot imagine doing it anywhere else. The skilled talent found here is second to Manitoba A provincial powerhouse none, and the innovative work being done is world class. -

Manitoba Hydro: the Long View

CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES MANITOBA Manitoba Hydro The Long View AUGUST 2019 By Lynne Fernandez Manitoba Hydro – The Long View About the Author isbn 978-1-77125-470-0 Lynne Fernandez holds the Errol Black Chair in Labour Issues at the Canadian Centre for Policy august 2019 Alternatives. This report is available free of charge from the CCPA Acknowledgements website at www.policyalternatives.ca. Printed The author would like to thank the three reviewers copies may be ordered through the Manitoba Office who provided corrections and improvements to the for a $10 fee. first draft. This research was supported by Manitoba’s labour Help us continue to offer our publications free online. community. We make most of our publications available free on our website. Making a donation or taking out a membership will help us continue to provide people with access to our ideas and research free of charge. You can make a donation or become a supporter on-line at www.policyalternatives.ca. Or you can contact the Manitoba office at 204-927-3200 for more information. Suggested donation for this publication: $10 or what you can afford. Unit 301-583 Ellice Ave., Winnipeg, MB R3B 1Z7 tel 204-927-3200 fax 204-927-3201 email [email protected] Table of Contents 1 Introduction 3 The Engine that Keeps the Province Going MH Finances 7 Keeyask Generating Station and Bipole III: A Short History Keeyask Generating System and the Need For and Alternatives To Hearings and Report – 2014 Demand Side Management 765 MW US Transmission Line First Nations -

Manitoba's Energy Supply

Manitoba’s energy supply: good for Manitobans, good for our environment Manitoba’s energy supply: good for Manitobans, good for our environment DID YOU KNOW? Manitoba has one of the most reliable electricity systems in the world and it is virtually emission free. Our electricity supply is renewable, effi cient, cost-effective and environmentally responsible. That is because over 97 per cent of the electricity generated in Manitoba is from renewable hydropower. Of electricity generated in Manitoba 97% is from renewable hydropower. Hydropower’s affordability, near-zero emissions, and ability to be delivered quickly to meet electricity demand have made it one of the most valuable renewable energy sources in the world. How is hydropower helping to combat climate change? One of the best ways to reduce greenhouse Suggested videos: gas emissions is to use less fossil fuel and • Benefi ts of hydropower: canadahydro.ca (2 minutes) more renewable energy. • The value of electricity exports: goo.gl/4zb2Qd (2 minutes) 2 Hydropower is renewable Once constructed, hydroelectric power plants have a long lifespan and are relatively Hydropower converts the energy from fl owing low maintenance. Some facilities in Manitoba water into electricity, without depleting water in are over 100 years old. the process. That means hydropower will be able to keep providing energy for generations to come. Hydropower is cost-effective Hydropower is virtually emission free and cost-competitive Hydropower combusts no fuel and produces While hydropower generating stations can no air pollutants or waste like those associated be costly to construct, once built they provide with fossil fuel or nuclear power. -

Pushing the Canada Manitoba Hydro

Pushing the Envelope A publication of the Ontario Building Envelope Council Canada Fall 2011 Manitoba Hydro Place: Canada Post Publications Agreement Number: 40609661 A Unique Building Envelope n n n TABLE OF CONTENTS Pushing the Envelope Canada UP FRONT A publication of the Ontario Building Envelope Council Message from the Incoming President ................................................................................ 9 Fall 2011 Published For: FEATURES The Ontario Building Envelope Council 2175 Sheppard Avenue, East Alaki Etching of Glass ........................................................................................................ 11 Suite 310 Manitoba Hydro Place: A Unique Building Envelope .................................................... 14 Toronto, ON M2J 1W8 Phone: 416-491-2886 Design for Daylight in Office Buildings ............................................................................ 19 Fax: 416-491-1670 Innovative Glass: Improving Energy Efficiency ............................................................... 22 [email protected] www.obec.on.ca First Canadian Place: Redefining an Icon ........................................................................ 24 The Emerging Power of Vacuum in Vacuum Insulation Panels ..................................... 26 Published By: Matrix Group Publishing Inc. Daylighting: More than Glass ............................................................................................ 28 Return all undeliverable addresses to: 52 Donald Street, Suite 300 Winnipeg, MB R3C -

Electricity Early Rural Electrification, Manitoba Power Commission

Manitoba “The Day the Light came on in Winnipeg”, in 1873, the Hon. R.H. Davis operated a “tremendous arc-light” to illuminate the front of his Davis House Hotel, on Main Street. The Winnipeg Gas Company was also incorporated in 1873. It was followed by the Manitoba Electric and Gas Light Company and the two merged in 1881. The City of Winnipeg enjoyed its first electric street lighting, by carbon-arc lamps, the following year in 1882. During the ensuing twenty-year period, to 1902, no less than six separate companies within Manitoba entered into the electric street railway and electric power generation businesses. The Winnipeg Electric Street Railway Company was formed in 1892. In 1904 its name was changed to Winnipeg Electric Railway Company and, by 1906, five of the six companies previously The Day the Light Came On in Winnipeg, 1873. referred to had either Photo courtesy of Manitoba Hydro and Manitoba Archives. merged or become subsidiaries of Winnipeg Electric Railway Company. The sixth company was located in Brandon and did not become part of the system until much later. The same year, 1906, the City of Winnipeg called for engineering studies to find a suitable site along the Winnipeg River for water power development. Pointe du Bois was selected and, in 191 1, the plant was pumping electric power over a 75 mile circuit to Winnipeg. By 1913 two new generators and a new double-circuit 69 kilovolt transmission line were added. This was the beginning of the Winnipeg Hydro as a Opening of Winnipeg Electric Street Railway-5th September, 1892.