Representations of Chinese Rock Bands”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Red Sonic Trajectories - Popular Music and Youth in China de Kloet, J. Publication date 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): de Kloet, J. (2001). Red Sonic Trajectories - Popular Music and Youth in China. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:08 Oct 2021 L4Trif iÏLK m BEGINNINGS 0 ne warm summer night in 1991, I was sitting in my apartment on the 11th floor of a gray, rather depressive building on the outskirts of Amsterdam, when a documentary on Chinese rock music came on the TV. I was struck by the provocative poses of Cui Jian, who blindfolded himself with a red scarf - stunned by the images of the crowds attending his performance, images that were juxtaposed with accounts of the student protests of June 1989; and puzzled, as I, a rather distant observer, always imagined China to be a totalitarian regime with little room for dissident voices. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

"World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 17:23 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump Canadian Perspectives in Ethnomusicology Résumé de l'article Perspectives canadiennes en ethnomusicologie This article traces the origins and uses of the musical classifications "world Volume 19, numéro 2, 1999 music" and "world beat." The term "world beat" was first used by the musician and DJ Dan Del Santo in 1983 for his syncretic hybrids of American R&B, URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014442ar Afrobeat, and Latin popular styles. In contrast, the term "world music" was DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar coined independently by at least three different groups: European jazz critics (ca. 1963), American ethnomusicologists (1965), and British record companies (1987). Applications range from the musical fusions between jazz and Aller au sommaire du numéro non-Western musics to a marketing category used to sell almost any music outside the Western mainstream. Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Klump, B. (1999). Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 19(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1999 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Prefab Compilation Album It's a Prefab World!

Contact: PreFab International Productions email: [email protected] web: prefabgroup.com PreFab compilation album It’s a PreFab World! released May 2012 American record label PreFab International Records is pleased to announce the release of it’s first compilation album It’s a PreFab World! The label, primarily known as a home for the recording projects of musician Phil Gammage, has assembled a stellar collection that highlights some of the best songs of the past few years from it’s catalog. What sets this compilation apart from the competition though, is the wealth of rare and previously unreleased tracks that make the bulk of the content. Featured songs from previous PreFab albums include “In Love Again” from The Scarlet Dukes (used in a 2008 Walmart commercial), Claudia’s version of Lou Reed’s “I’ll Be Your Mirror” from her debut CD single, downtown legends Certain General with their classic “Maximum G” from the essential Live at the Public Theatre, and Phil’s “Nueva York” from his jazz instrumental collection Tracks of Sound The rare and previously unreleased music from these artists that appear on It’s a PreFab World! are as strong or exceed the featured songs from their other PreFab albums. Certain General scores with the moody “I’ll Behave”. Songstress Claudia showcases her talents with her unique versions of Nirvana’s “About a Girl” and label-mates Certain General’s composition “Heathcliff Skies”. Gammage stretches out on guitar in the instrumental workouts “Third Avenue Wind Tunnel” and “Stacey Says”. And Phil’s neo-lounge project Voodoo Martini re-emerges with a new lineup and their first new recordings in over a decade (!?) with “Naked in the Rain”, “I Kissed My Girl”, and others. -

Iacs2017 Conferencebook.Pdf

Contents Welcome Message •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 Conference Program •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 Conference Venues ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 Keynote Speech ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 16 Plenary Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 20 Special Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 34 Parallel Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 40 Travel Information •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 228 List of participants ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 232 Welcome Message Welcome Message Dear IACS 2017 Conference Participants, I’m delighted to welcome you to three exciting days of conferencing in Seoul. The IACS Conference returns to South Korea after successful editions in Surabaya, Singapore, Dhaka, Shanghai, Bangalore, Tokyo and Taipei. The IACS So- ciety, which initiates the conferences, is proud to partner with Sunkonghoe University, which also hosts the IACS Con- sortium of Institutions, to organise “Worlding: Asia after/beyond Globalization”, between July 28 and July 30, 2017. Our colleagues at Sunkunghoe have done a brilliant job of putting this event together, and you’ll see evidence of their painstaking attention to detail in all the arrangements -

How to Share Music in Many Complicated Steps

HOW TO SHARE MUSIC IN MANY COMPLICATED STEPS Songwriter Gives permission to Music Publisher Gives permission to use song in film or tv use song in Accepts transferred copyright in dramatic work SYNCHRONIZATION exchange for paying royalties RIGHTS GRAND RIGHTS Contracts with: Mechanical Rights Company Performing Rights Society (ie: Harry Fox Agency) (ie: ASCAP, BMI) Control permission to make and License use of the recording for radio, distribute the recording of a song store background, ringtones, etc PERFORMANCE RIGHTS MECHANICAL RIGHTS OR the song itself to sing in public SMALL RIGHTS Recording Company (ie: Arista Records) Gives permission to Create original “professional” use recording in film recording or single or album or tv Gets permission to make album MASTER USE RIGHTS –pays royalty for album sales -makes available to performing rights society HOW TO SHARE MUSIC IN MANY COMPLICATED STEPS Definitions Synchronization Rights: The right to use the music in timed relations with other visual elements in a film, video, television show/commercial, or other audio/visual production. In other words, the right to use the music as a soundtrack with visual images. Synchronization licenses are obtained from the publisher (or composer if no publisher) or the music library. Master Use Rights: When you hear music in a film or on TV, this recording is known in the music industry as the "master recording". This is what is produced after all the musicians have played their parts and these parts have been "mixed" together for release. The recording of the master is also protected by copyright. A record label or music library owns this copyright, and can grant the right to use the recording in a compilation album, film soundtrack or other Audio/Visual medium. -

Art to Commerce: the Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism

Art to Commerce: The Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism Thomas Conner and Steve Jones University of Illinois at Chicago [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract This article reports the results of a content and textual analysis of popular music criticism from the 1960s to the 2000s to discern the extent to which criticism has shifted focus from matters of music to matters of business. In part, we believe such a shift to be due likely to increased awareness among journalists and fans of the industrial nature of popular music production, distribution and consumption, and to the disruption of the music industry that began in the late 1990s with the widespread use of the Internet for file sharing. Searching and sorting the Rock’s Backpages database of over 22,000 pieces of music journalism for keywords associated with the business, economics and commercial aspects of popular music, we found several periods during which popular music criticism’s focus on business-related concerns seemed to have increased. The article discusses possible reasons for the increases as well as methods for analyzing a large corpus of popular music criticism texts. Keywords: music journalism, popular music criticism, rock criticism, Rock’s Backpages Though scant scholarship directly addresses this subject, music journalists and bloggers have identified a trend in recent years toward commerce-specific framing when writing about artists, recording and performance. Most music journalists, according to Willoughby (2011), “are writing quasi shareholder reports that chart the movements of artists’ commercial careers” instead of artistic criticism. While there may be many reasons for such a trend, such as the Internet’s rise to prominence not only as a medium for distribution of music but also as a medium for distribution of information about music, might it be possible to discern such a trend? Our goal with the research reported here was an attempt to empirically determine whether such a trend exists and, if so, the extent to which it does. -

The Pop Scene Around the World Andrew Clawson Iowa State University

Volume 2 Article 13 12-2011 The pop scene around the world Andrew Clawson Iowa State University Emily Kudobe Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/revival Recommended Citation Clawson, Andrew and Kudobe, Emily (2011) "The pop cs ene around the world," Revival Magazine: Vol. 2 , Article 13. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/revival/vol2/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Revival Magazine by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Clawson and Kudobe: The pop scene around the world The POP SCENE Around the World Taiwan Hong Kong Japan After the People’s Republic of China was Japan is the second largest music market Hong Kong can be thought of as the Hol- established, much of the music industry in the world. Japanese pop, or J-pop, is lywood of the Far East, with its enormous left for Taiwan. Language restrictions at popular throughout Asia, with artists such film and music industry. Some of Asia’s the time, put in place by the KMT, forbade as Utada Hikaru reaching popularity in most famous actors and actresses come the use of Japanese language and the the United States. Heavy metal is also very from Hong Kong, and many of those ac- native Hokkien and required the use of popular in Japan. Japanese rock bands, tors and actresses are also pop singers. -

An Ideological Analysis of the Birth of Chinese Indie Music

REPHRASING MAINSTREAM AND ALTERNATIVES: AN IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BIRTH OF CHINESE INDIE MUSIC Menghan Liu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill Esther Clinton © 2012 MENGHAN LIU All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis project focuses on the birth and dissemination of Chinese indie music. Who produces indie? What is the ideology behind it? How can they realize their idealistic goals? Who participates in the indie community? What are the relationships among mainstream popular music, rock music and indie music? In this thesis, I study the production, circulation, and reception of Chinese indie music, with special attention paid to class, aesthetics, and the influence of the internet and globalization. Borrowing Stuart Hall’s theory of encoding/decoding, I propose that Chinese indie music production encodes ideologies into music. Pierre Bourdieu has noted that an individual’s preference, namely, tastes, corresponds to the individual’s profession, his/her highest educational degree, and his/her father’s profession. Whether indie audiences are able to decode the ideology correctly and how they decode it can be analyzed through Bourdieu’s taste and distinction theory, especially because Chinese indie music fans tend to come from a community of very distinctive, 20-to-30-year-old petite-bourgeois city dwellers. Overall, the thesis aims to illustrate how indie exists in between the incompatible poles of mainstream Chinese popular music and Chinese rock music, rephrasing mainstream and alternatives by mixing them in itself. -

Charles Peterson …And Everett True Is 481

Dwarves Photos: Charles Peterson …and Everett True is 481. 19 years on from his first Seattle jolly on the Sub Pop account, Plan B’s publisher-at-large jets back to the Pacific Northwest to meet some old friends, exorcise some ghosts and find out what happened after grunge left town. How did we get here? Where are we going? And did the Postal Service really sell that many records? Words: Everett True Transcripts: Natalie Walker “Heavy metal is objectionable. I don’t even know comedy genius, the funniest man I’ve encountered like, ‘I have no idea what you’re doing’. But he where that [comparison] comes from. People will in the Puget Sound8. He cracks me up. No one found trusted the four of us enough to let us go into the say that Motörhead is a metal band and I totally me attractive until I changed my name. The name studio for a weekend and record with Jack. It was disagree, and I disagree that AC/DC is a metal band. slides into meaninglessness. What is the Everett True essentially a demo that became our first single.” To me, those are rock bands. There’s a lot of Chuck brand in 2008? What does Sub Pop stand for, more Berry in Motörhead. It’s really loud and distorted and than 20 years after its inception? Could Sub Pop It’s in the focus. The first time I encountered Sub amplified but it’s there – especially in the earlier have existed without Everett True? Could Everett Pop, I had 24 hours to write up my first cover feature stuff. -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

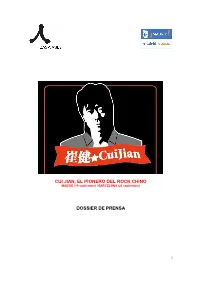

DOSSIER PRENSA CUI JIAN EN ESPAÑA Pdf

CUI JIAN, EL PIONERO DEL ROCK CHINO MADRID (19 septiembre) / BARCELONA (23 septiembre) DOSSIER DE PRENSA 1 INDICE 1.- PRESENTACIÓN: CUI JIAN, LA GRAN ESTRELLA DEL ROCK CHINO…..……. pág. 03 1.1. NOTA DE PRENSA: CASA ASIA PRESENTA A CUI JIAN EN MADRID Y BARCELONA 1.2. CUI JIAN: BIOGRAFÍA RESUMIDA 2.- BIOGRAFÍA DE CUI JIAN, ICONO DE LA CHINA CONTEMPORÁNEA……….…pág. 06 2.1. EL COMIENZO DE SU CARRERA 2.2. CUI JIAN, MÚSICO COMPROMETIDO 2.3. EL CUI JIAN DEL NUEVO MILENIO 2.4. SU CARRERA EN IMÁGENES 2.5. DISCOGRAFÍA DE CUI JIAN 3.- CUI JIAN Y EL CINE………………………………………………………………….….. pág. 12 3.1. FILMOGRAFÍA DE CUI JIAN 4.- MÁS INFORMACIÓN…………………………………………………………..…………pág. 14 4.1. CUI JIAN Y LOS MIEMBROS SU GRUPO 4.2. LETRAS DE CUI JIAN: REPERTORIO EN MADRID Y BARCELONA 5.- LINKS DE REFERENCIA, REPORTAJES, ENTREVISTAS Y VÍDEOS…….....….. pág. 19 6.- CONTACTO DE PRENSA……………………………………………………………….. pág. 20 2 1.- PRESENTACIÓN: CUI JIAN, LA GRAN ESTRELLA DEL ROCK CHINO La China de hoy es una gran potencia en todos los campos, pero su cultura contemporánea sigue siendo muy desconocida en el mundo occidental. Cui Jian, considerado el padre del rock en China y un artista polifacético y comprometido, es una de las voces imprescindibles para conocer la nueva China. Casa Asia –un consorcio público encargado de promover el conocimiento de Asia en España—acerca este artista al público español con dos conciertos en Madrid y Barcelona, que servirán para dar a conocer a una figura clave para entender la música actual china. En sus 25 años de carrera, el guitarrista, trompetista, cantante y compositor chino ha conseguido el estatus de artista de talento transversal al implicarse en todos los procesos de la creación artística.