The 21: a Journey to the Land of Coptic Martyrs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legion HANDBOOK D10944

THE OFFICIAL HANDBOOK OF THE LEGION OF MARY PUBLISHED BY CONCILIUM LEGIONIS MARIAE DE MONTFORT HOUSE MORNING STAR AVENUE BRUNSWICK STREET DUBLIN 7, IRELAND Revised Edition, 2005 Nihil Obstat: Bede McGregor, O.P., M.A., D.D. Censor Theologicus Deputatus. Imprimi potest: ✠ Diarmuid Martin Archiep. Dublinen. Hiberniae Primas. Dublin, die 8 September 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal © 1973, International Committee on English in the Liturgy, Inc. All rights reserved. Translation of The Magnificat by kind permission of A. P. Watt Ltd. on behalf of The Grail. Extracts from English translations of documents of the Magisterium by kind permission of the Catholic Truth Society (London) and Veritas (Dublin). Quotation on page 305 by kind permission of Sheed and Ward. The official magazine of the Legion of Mary, Maria Legionis, is published quarterly Presentata House, 263 North Circular Road, Dublin 7, Ireland. © Copyright 2005 Printed in the Republic of Ireland by Mahons, Yarnhall Street, Dublin 1 Contents Page ABBREVIATIONS OF BOOKS OF THE BIBLE ....... 3 ABBREVIATIONS OF DOCUMENTS OF THE MAGISTERIUM .... 4 POPE JOHN PAUL II TO THE LEGION OF MARY ...... 5 PRELIMINARY NOTE.............. 7 PROFILE OF FRANK DUFF .......... 8 PHOTOGRAPHS:FRANK DUFF .......facing page 8 LEGION ALTAR ......facing page 108 VEXILLA ........facing page 140 CHAPTER 1. Name and Origin ............ 9 2. Object . ...............11 3. Spirit of the Legion . ...........12 4. Legionary service ............13 5. The Devotional Outlook of the Legion .....17 6. The Duty of Legionaries towards Mary .....25 7. The Legionary and the Holy Trinity ......41 8. The Legionary and the Eucharist .......45 9. -

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010 1. Please provide detailed information on Al Minya, including its location, its history and its religious background. Please focus on the Christian population of Al Minya and provide information on what Christian denominations are in Al Minya, including the Anglican Church and the United Coptic Church; the main places of Christian worship in Al Minya; and any conflict in Al Minya between Christians and the authorities. 1 Al Minya (also known as El Minya or El Menya) is known as the „Bride of Upper Egypt‟ due to its location on at the border of Upper and Lower Egypt. It is the capital city of the Minya governorate in the Nile River valley of Upper Egypt and is located about 225km south of Cairo to which it is linked by rail. The city has a television station and a university and is a centre for the manufacture of soap, perfume and sugar processing. There is also an ancient town named Menat Khufu in the area which was the ancestral home of the pharaohs of the 4th dynasty. 2 1 „Cities in Egypt‟ (undated), travelguide2egypt.com website http://www.travelguide2egypt.com/c1_cities.php – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 1. 2 „Travel & Geography: Al-Minya‟ 2010, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2 August http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/384682/al-Minya – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 2; „El Minya‟ (undated), touregypt.net website http://www.touregypt.net/elminyatop.htm – Accessed 26 July 2010 – Page 1 of 18 According to several websites, the Minya governorate is one of the most highly populated governorates of Upper Egypt. -

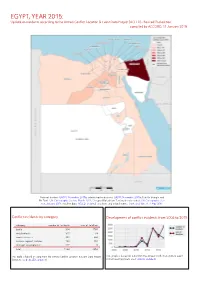

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Pdf (925.83 K)

Journal of Engineering Sciences, Assiut University, Vol. 37, No. 5, pp. 1193-1207, September 2009. EVALUATION OF GROUNDWATER AQUIFER IN THE AREA BETWEEN EL-QUSIYA AND MANFALUT USING VERTICAL ELECTRIC SOUNDINGS (VES) TECHNIQUE 1 2 3 Waleed S.S. , Abd El-Monaim, A, E. , Mansour M.M. and El-Karamany M. F.3 1 Ministry of Water Resources (underground water sector) 2 Research Institute for Groundwater 3 Mining & Met. Dept., Faculty of Eng., Assiut University (Received August 5, 2009 Accepted August 17, 2009). The studied area is located northwest of Assiut city which represents a large part of the Nile Valley in Assiut governorate. It lies between latitudes 27° 15ƍ 00Ǝ and 27° 27ƍ 00Ǝ N, and longitudes 30° 42ƍ 30Ǝ to 31° 00ƍ E, covering approximately 330 square kilometers. Fifteen Vertical Electrical soundings (VES) were carried out to evaluate the aquifer in the study area. These soundings were arranged to construct three geoelectric profiles crossing the Nile Valley. Three cross sections were constructed along these profiles to detect the geometry and geoelectric characteristics of the quaternary aquifer based on the interpretation of the sounding curves and the comparison with available drilled wells. The interpretation showed that the thickness of the quaternary aquifer in the study area ranges between 75 and 300 m, in which the maximum thicknesses are detected around Manfalut and at the west of El-Qusiya. INTRODUCTION During the two last decades, there is a continuous demand for big amount of water necessary for the land expansion projects in Egypt. So, the development of groundwater resources receives special attention, since the groundwater reservoir underlying the Nile Valley and its adjacent desert areas acting as auxiliary source of water in Egypt. -

A NEW OLD KINGDOM INSCRIPTION from GIZA (CGC 57163), and the PROBLEM of Sn-Dt in PHARAONIC THIRD MILLENNIUM SOCIETY

THE JOUR AL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 93 2007 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY ~IEWS, LONDON wei?'; 2PG ISSN 0307-5133 THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 93 2°°7 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 3 DOUGHTY MEWS, LONDON WCIN zPG CONTENTS EDITORIAL FOREWORD Vll TELL EL-AMARNA, 2006-7 Barry Kemp THE DELTA SURVEY: MINUFIYEH PROVINCE, 2006-7 Joanne Rowland 65 THE GEOPHYSICAL SURVEY OF NORTH SAQQARA, 2001-7 . Ian Mathieson and Jon Dittmer. 79 AN ApPRENTICE'S BOARD FROM DRA ABU EL-NAGA . Jose M. Galan . 95 A NEW OLD KINGDOM INSCRIPTION FROM GIZA (CGC 57163), AND THE PROBLEM OF sn-dt IN PHARAONIC THIRD MILLENNIUM SOCIETY . Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia . · 117 A DEMOTIC INSCRIBED ICOSAHEDRON FROM DAKHLEH OASIS Martina Minas-Nerpel 137 THE GOOD SHEPHERD ANTEF (STELA BM EA 1628). Detlef Franket . 149 WORK AND COMPENSATION IN ANCIENT EGYPT David A. Warburton 175 SOME NOTES ON THE FUNERARY CULT IN THE EARLY MIDDLE KINGDOM: STELA BM EA 1164 . Barbara Russo . · 195 ELLIPSIS OF SHARED SUBJECTS AND DIRECT OBJECTS FROM SUBSEQUENT PREDICATIONS IN EARLIER EGYPTIAN . Carsten Peust · 211 THE EVIL STEPMOTHER AND THE RIGHTS OF A SECOND WIFE. Christopher J. Eyre . · 223 BRIEF COMMUNICATIONS FIGHTING KITES: BEHAVIOUR AS A KEY TO SPECIES IDENTITY IN WALL SCENES Linda Evans · 245 ERNEST SIBREE: A FORGOTTEN PIONEER AND HIS MILIEU Aidan Dodson . · 247 AN EARLY DYNASTIC ROCK INSCRIPTION AT EL-HoSH. Ilona Regulski . · 254 MISCELLANEA MAGICA, III: EIN VERTAUSCHTER KOPF? KONJEKTURVORSCHLAG FUR P. BERLIN P 8313 RO, COL. II, 19-20. Tonio Sebastian Richter. · 259 A SNAKE-LEGGED DIONYSOS FROM EGYPT, AND OTHER DIVINE SNAKES Donald M. -

A Church That Teaches: a Guide to Our Lady of the Most Holy Trinity

A Church that Teaches A Guide to Our Lady of the Most Holy Trinity Chapel at Thomas Aquinas College A Church that Teaches A Guide to Our Lady of the Most Holy Trinity Chapel at Thomas Aquinas College Second Edition © 2010 quinas A C s o a l m l e o g h e T C 1 al 7 if 19 ornia - 10,000 Ojai Road, Santa Paula, CA 93060 • 800-634-9797 www.thomasaquinas.edu Foreword “This college will explicitly define itself by the Christian Faith and the tradition of the Catholic Church.” — A Proposal for the Fulfillment of Catholic Liberal Education (1969) Founding document of Thomas Aquinas College Dear Friend, In setting out on their quest to restore Catholic liberal education in the United States, the founders of Thomas Aquinas College were de- termined that at this new institution faith would be more than simply an adornment on an otherwise secular education. The intellectual tra- dition and moral teachings of the Catholic Church would infuse the life of the College, illuminating all learning as well as the community within which learning takes place. Just as the Faith would lie at the heart of Thomas Aquinas College, so too would a beautiful chapel stand at the head of its campus. From the time the College relocated in 1978 to its site near Santa Paula, plans were in place to build a glorious house of worship worthy of the building’s sacred purpose. Those plans were long deferred, however, due to financial limitations and the urgent need to establish basic campus essentials such as dining facilities, residence halls, and classrooms. -

St. Shenouda Center for Coptic Studies

St. Shenouda Coptic Library AuthorName_Year Title Publisher Topic Name: HAGIOGRAPHY ABD AL-NOUR, RAGHEB. HEGUMEN BISHOY KAMEL AND HIS INTERCESSIONS SHUBRA: MAKTABAT MARI GIRGIS. 1988. AL-MUHARRAQI, LIFE OF SAINT MIKAIL AL BEHERY ASYUT: DEIR AL-MUHARRAQ. BACHOMUS. 1993. AMELINEAU, EMILE LES ACTES DES MARTYRS DE L'EGLISE COPTE PARIS: ERNEST LEROUX. CLEMENT. 1890. ANBA DEMADIUOS. 1989. THE NEW MARTYR SAINT BISTAVROS ANBA MENA. 1990. THE STORY OF THE NEW SAINT, SAINT ABDELMESSIH AL MAKKARY BANY SWEEF: LAGNET AL TAHHRER WA AL NASHR. ANBA META'AOS. 1992. THE GREAT MARTYR ABBA ASKHYRON AL KELENY CAIRO: ANBA REUISS PRESS. ANBA META'AOS. 1992. THE LIFE, MIRCALS AND CHURCHES OF THE MARTYRS ABIKEIR AND YOHANA ANBA META'AOS. 1993. THE GREAT MARTYR ISSAC AL DARFARAWY CAIRO: SAINT MARY'S CHURCH. ANBA META'AOS. n.d.. THE LIFE OF MALCHESADEK ANBA YOWAKIM. 1992. THE LIFE OF FATHER ABRAAM AL BASET ANONYMOUS. 1976. THE GREAT SAINT ABOU-SEFIEN SHUBRA: MAKTABAT MARI GIRGIS. ANONYMOUS. 1981. THE SAINT ANBA BARSOUM AL ARYAN CAIRO: MAHABBA BOOKSTORE. ANONYMOUS. 1985. SAINT MINA THE MIRACLE WORKER: HIS LIFE AND HIS MIRACLES CAIRO: ABNAA AL BABA KYRILLOS VI. ANONYMOUS. 1987. MIRACLES OF MAR MINA THE WONDER WORKER II CAIRO: ABNAA AL BABA KYRILLOS VI. ANONYMOUS. 1987. MIRACLES OF POPE KYRILLOS VI PART FIVE CAIRO: ABNAA AL BABA KYRILLOS VI. ANONYMOUS. 1987. MIRACLES OF POPE KYRILLOS VI PART SEVEN CAIRO: ABNAA AL BABA KYRILLOS VI. ANONYMOUS. 1987. MIRACLES POPE KYRILLOS VI PART TWO CAIRO: ABNAA AL BABA KYRILLOS VI. ANONYMOUS. 1988. ANBA RUWAYS CAIRO: ABNNA AL ANBA RUWAYS. ANONYMOUS. 1988. MIRACLES OF POPE KYRILLOS VI PART ONE CAIRO: ABNAA AL BABA KYRILLOS VI. -

Coptic Church Review

ISSN 0273-3269 COPTIC CHURCH REVIEW Volume 20, Number 4 . Winter 1999 •The Impact of Copts on Civilization •The Brotherhood of Ps-Macarius •Ecumenical Desert Monasticism •Priesthood Between St. Gregory and St. Chrysostom Society of Coptic Church Studies EDITORIAL BOARD COPTIC CHURCH REVIEW Bishop Wissa (Al-Balyana, Egypt) A Quarterly of Contemporary Patristic Studies Bishop Antonious Markos ISSN 0273-3269 (Coptic Church, African Affairs) Volume 20, Number 4 . .Winter 1999 Bishop Isaac (Quesna, Egypt) Bishop Dioscorus 98 The Impact of Copts on (Coptic Church, Egypt) Civilization* Fr. Tadros Malaty Amin Makram Ebeid (Alexandria, Egypt) Professor Fayek Ishak (Ontario, Canada) 119 The Brotherhood of Ps-Macarius William El-Meiry, Ph.D. Stuart Burns (N.J., U.S.A.) Girgis A. Ibrahim, Ph.D. (Florida, U.S.A.) 127 Previous Issues of CCR Esmat Gabriel, Ed.D. (PA., U.S.A.) 128 Ecumenical Desert Monasticism EDITOR Otto Meinardus Rodolph Yanney, M.D. CIRCULATION MANAGER Ralph Yanney 135 Priesthood between St. Gregory © Copyright 1999 and St. Chrysostom by Coptic Church Review Rodolph Yanney E. Brunswick, NJ Subscription and Business Address: Society of Coptic Church Studies 142 Book Reviews P.0. Box 714, E. Brunswick, NJ 08816 • Ancient Israel: Life and email: [email protected] Institutions Editorial Address: Coptic Church Review •The Hidden Life of the P.O. Box 1113, Lebanon, PA 17042 Carthusians email: [email protected] Subscription Price (1 Year) U.S.A. $10.00 143 Index of Volume 20, 1999 Canada $12.00 (U.S. dollars) Overseas $13.00 Articles are indexed in Religion Index Back Calendar of Fasts and Feasts One: Periodicals; book reviews are Cover indexed in Index to Book Reviews in Religion. -

Freedom of Religion and Belief in Egypt Quarterly Report (October - December 2008)

Freedom of Religion and Belief in Egypt Quarterly Report (October - December 2008) Freedom of Religion and Belief Program Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights January 2009 This report This report addresses several of the most significant developments seen in Egypt in the field of freedom of religion and belief in the months of October, November, and December of 2008. The report observes continued sectarian tension and violence all over Egypt and documents cases in the governorates of Cairo, Alexandria, Qalyoubiya, Sharqiya, Kafr al-Sheikh, Minya, and Luxor. As usual, Minya accounted for the lion’s share of incidents of sectarian violence, with cases in the district of Matay, the village of Kom al-Mahras, and the district of Abu Qurqas, as well as events in the village of al-Tayiba in the Samalut district in October. The latter were the worst of the fourth quarter of 2008, leaving one Christian dead and four other people injured, among them one Muslim. Homes, lands, and property were also torched and damaged. The report also notes increased tensions and clashes as a result of Copts establishing “service centers” to use for social occasions, prayers, or religious lessons in neighborhoods and villages that have no nearby churches or in cases where Copts have failed to obtain permits to build a new church or renovate an existing church. The report discusses several instances in which the establishment of such centers, or rumors that attempts were being made to convert them into churches, led to sectarian clashes. Events in November in the Ain Shams area of Cairo received the most media coverage in this regard, but two similar incidents took place in the village of Kafr Girgis in the Minya al-Qamh district of Sharqiya and in the al-Iraq village in Alexandria’s al- Amiriya neighborhood. -

MOST ANCIENT EGYPT Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu MOST ANCIENT EGYPT oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber MOST ANCIE NT EGYPT William C. Hayes EDITED BY KEITH C. SEELE THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO & LONDON oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-17294 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada © 1964, 1965 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1965. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu WILLIAM CHRISTOPHER HAYES 1903-1963 oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu INTRODUCTION WILLIAM CHRISTOPHER HAYES was on the day of his premature death on July 10, 1963 the unrivaled chief of American Egyptologists. Though only sixty years of age, he had published eight books and two book-length articles, four chapters of the new revised edition of the Cambridge Ancient History, thirty-six other articles, and numerous book reviews. He had also served for nine years in Egypt on expeditions of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the institution to which he devoted his entire career, and more than four years in the United States Navy in World War II, during which he was wounded in action-both periods when scientific writing fell into the background of his activity. He was presented by the President of the United States with the bronze star medal and cited "for meritorious achievement as Commanding Officer of the U.S.S. VIGILANCE ... in the efficient and expeditious sweeping of several hostile mine fields.., and contributing materially to the successful clearing of approaches to Okinawa for our in- vasion forces." Hayes' original intention was to work in the field of medieval arche- ology. -

The True Story of Christianity in Egypt

THE STORY OF THE COPTS THE TRUE STORY OF CHRISTIANITY IN EGYPT by Iris Habib el Masri BOOK 1 FROM THE FOUNDATION OF THE CHURCH BY SAINT MARK TO THE ARAB CONQUEST 2 Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ King of Kings and Lord of lords 3 H.H. Pope Shenouda III, 117th Pope of Alexandria and the See of St. Mark 4 St. Anthony, Coptic Orthodox Monastery of Southern California, U.S.A., introduces "The Story of the Copts" by IRIS HABIB EL MASRI to all Christians and non-Christians; to old and young; men and women; ... to everyone, with or without an interest in studying religion; and to the public in general. Also, the Copts in Egypt and all over the world. May God grant that the reader gain a true knowledge of the Copts and of the history of Christianity of Egypt. ST. ANMNY MONASTERY P.O. BOX 369 MMERRY SPRINGS, CA 923$5 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is with deep gratitude that I offer my thanks to our Heavenly Father whose aid and guidance have been my lodestar throughout the years. My thankful homage to the Spirit of my Father Pishoi Kamil whose encouragement by prayer, words and continued endeavour added to my zeal and fervour, and strengthened me to persevere on the path towards fulfilment. My thanks are extended also to all my family circle and friends, with special appreciation to the budding artist Habib Amin el Masri, my nephew, for giving me some of his paintings to adorn this volume. As for my sister Eva el Masri Sidhom, I consider he my co-writer; she and her husband Youssef did their best in editing and typing this work. -

The Impact of the Arab Conquest on Late Roman Settlementin Egypt

Pýý.ý577 THE IMPACT OF THE ARAB CONQUEST ON LATE ROMAN SETTLEMENTIN EGYPT VOLUME I: TEXT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY CAMBRIDGE This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Cambridge, March 2002 ALISON GASCOIGNE DARWIN COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE For my parents with love and thanks Abstract The Impact of the Arab Conquest on Late Roman Settlement in Egypt Alison Gascoigne, Darwin College The Arab conquest of Egypt in 642 AD affected the development of Egyptian towns in various ways. The actual military struggle, the subsequent settling of Arab tribes and changes in administration are discussed in chapter 1, with reference to specific sites and using local archaeological sequences. Chapter 2 assesseswhether our understanding of the archaeological record of the seventh century is detailed enough to allow the accurate dating of settlement changes. The site of Zawyet al-Sultan in Middle Egypt was apparently abandoned and partly burned around the time of the Arab conquest. Analysis of surface remains at this site confirmed the difficulty of accurately dating this event on the basis of current information. Chapters3 and 4 analysethe effect of two mechanismsof Arab colonisation on Egyptian towns. First, an investigation of the occupationby soldiers of threatened frontier towns (ribats) is based on the site of Tinnis. Examination of the archaeological remains indicates a significant expansion of Tinnis in the eighth and ninth centuries, which is confirmed by references in the historical sources to building programmes funded by the central government. Second, the practice of murtaba ` al- jund, the seasonal exploitation of the town and its hinterland for the grazing of animals by specific tribal groups is examined with reference to Kharibta in the western Delta.