Grand Experiment of Joe Paterno

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Following Players Comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set

COLLEGE FOOTBALL GREAT TEAMS OF THE PAST 2 SET ROSTER The following players comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. 1971 NEBRASKA 1971 NEBRASKA 1972 USC 1972 USC OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Woody Cox End: John Adkins EB: Lynn Swann TA End: James Sims Johnny Rodgers (2) TA TB, OA Willie Harper Edesel Garrison Dale Mitchell Frosty Anderson Steve Manstedt John McKay Ed Powell Glen Garson TC John Hyland Dave Boulware (2) PA, KB, KOB Tackle: John Grant Tackle: Carl Johnson Tackle: Bill Janssen Chris Chaney Jeff Winans Daryl White Larry Jacobson Tackle: Steve Riley John Skiles Marvin Crenshaw John Dutton Pete Adams Glenn Byrd Al Austin LB: Jim Branch Cliff Culbreath LB: Richard Wood Guard: Keith Wortman Rich Glover Guard: Mike Ryan Monte Doris Dick Rupert Bob Terrio Allan Graf Charles Anthony Mike Beran Bruce Hauge Allan Gallaher Glen Henderson Bruce Weber Monte Johnson Booker Brown George Follett Center: Doug Dumler Pat Morell Don Morrison Ray Rodriguez John Kinsel John Peterson Mike McGirr Jim Stone ET: Jerry List CB: Jim Anderson TC Center: Dave Brown Tom Bohlinger Brent Longwell PC Joe Blahak Marty Patton CB: Charles Hinton TB. -

Gis'death Toll Rises at the Same Time a State Department Spokesman Prod- SAIGON (AP) - the Num- U.S

gfam SEE STORY BELOW Windy Cold, windy with chance' of HOME few snow flurries today. Hed Bank, Freehold f Clearing, colder tonight and tomorrow. Long Branch J FINAL -1 (Bet Settlla Pag» 2) Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 114 RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, DECEMBER 5,1968 46 PAGfS TEN CENTS U.S. Presses for Mideast Peace By JOHN M. HIGHTOWER article which touches on a not had evidence of compar- dor Abdul Hamid Sharaf were cern," McCloskey said, "over Israeli and Jordanian repre- WASHINGTON (AP) - The number pf points," McClos- able Soviet exertions in the summoned separately to the the situation in the Middle sentatives in New York and to United States is trying ur- key said. "What we are look- interest of peace. State Department Wednesday East presently. Violations of take the same line with them. gently through diplomatic ing for, however, is concrete Arms to Both afternoon and told of deep the cease-fire line by either JJ.N. Special Envoy Gunner pressure to prevent further evidence that the Soviets are The United States itself is U.S. concern over events in or both sides serve only to Jarring has recently arrived ' escalation of the Israel-Arab exerting their influence to- supplying arms to both Israel the Mideast. heighten tensions in the area in Cairo on a new round of and hinder the efforts of the border • clashes which have ward peace in the Middle and Jordan, which has tradi- U.S. officials indicated the peace making activities fol- intensified the Middle East East. -

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release Game 12: Miami Dolphins (4-7) vs. Baltimore Ravens (4-7) Sunday, Dec. 6 • 1 p.m. ET • Sun Life Stadium • Miami Gardens, Fla. RESHAD JONES Tackle total leads all NFL defensive backs and is fourth among all NFL 20 / S 98 defensive players 2 Tied for first in NFL with two interceptions returned for touchdowns Consecutive games with an interception for a touchdown, 2 the only player in team history Only player in the NFL to have at least two interceptions returned 2 for a touchdown and at least two sacks 3 Interceptions, tied for fifth among safeties 7 Passes defensed, tied for sixth-most among NFL safeties JARVIS LANDRY One of two players in NFL to have gained at least 100 yards on rushing (107), 100 receiving (816), kickoff returns (255) and punt returns (252) 14 / WR Catch percentage, fourth-highest among receivers with at least 70 71.7 receptions over the last two years Of two receivers in the NFL to have a special teams touchdown (1 punt return 1 for a touchdown), rushing touchdown (1 rushing touchdown) and a receiving touchdown (4 receiving touchdowns) in 2015 Only player in NFL with a rushing attempt, reception, kickoff return, 1 punt return, a pass completion and a two point conversion in 2015 NDAMUKONG SUH 4 Passes defensed, tied for first among NFL defensive tackles 93 / DT Third-highest rated NFL pass rush interior defensive lineman 91.8 by Pro Football Focus Fourth-highest rated overall NFL interior defensive lineman 92.3 by Pro Football Focus 4 Sacks, tied for sixth among NFL defensive tackles 10 Stuffs, is the most among NFL defensive tackles 4 Pro Bowl selections following the 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INFORMATION 4-5 2015 MIAMI DOLPHINS SEASON SCHEDULE 6-7 MIAMI DOLPHINS 50TH SEASON ALL-TIME TEAM 8-9 2015 NFL RANKINGS 10 2015 DOLPHINS LEADERS AND STATISTICS 11 WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN 2015/WHAT TO LOOK FOR AGAINST THE RAVENS 12 DOLPHINS-RAVENS OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE COMPARISON 13 DOLPHINS PLAYERS VS. -

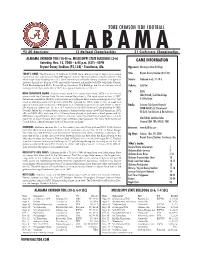

2008 Alabama FB Game Notes

2008 CRIMSON TIDE FOOTBALL 92 All-Americans ALABAMA12 National Championships 21 Conference Championships ALABAMA CRIMSON TIDE (10-0) vs. MISSISSIPPI STATE BULLDOGS (3-6) GAME INFORMATION Saturday, Nov. 15, 2008 - 6:45 p.m. (CST) - ESPN Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) - Tuscaloosa, Ala. Opponent: Mississippi State Bulldogs TODAY’S GAME: The University of Alabama football team returns home to begin a two-game Site: Bryant-Denny Stadium (92,138) homestand that will close out the 2008 regular season. The top-ranked Crimson Tide host the Mississippi State Bulldogs in a SEC West showdown at Bryant-Denny Stadium. The game is Series: Alabama leads, 71-18-3 slated to kickoff at 6:45 p.m. (CST) and will be televised nationally by ESPN with Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge and Holly Rowe calling the action. The Bulldogs are 3-6 on the season and Tickets: Sold Out coming off of a bye week after a 14-13 loss against Kentucky on Nov. 1. TV: ESPN HEAD COACH NICK SABAN: Alabama head coach Nick Saban (Kent State, 1973) is in his second season with the Crimson Tide. He was named the school’s 27th head coach on Jan. 3, 2007. Mike Patrick, Todd Blackledge Saban has compiled a 108-48-1 (.691) record as a collegiate head coach, including an 17-6 (.739) & Holly Rowe mark at Alabama and a 10-0 record in 2008. He captured his 100th career victory in week two against Tulane and coached his 150th game as a collegiate head coach in week three vs. West- Radio: Crimson Tide Sports Network ern Kentucky. -

Crimson White Gameday

GAMEDAY'07 A-Day game preview The Saban Era At the end of g Spring practice recap spring training, g A talk with Terry Saban Saban to make g Photo feature: Saban’s arrival A-Day debut IfIf youyou wantwant toto fitfit in,in, you’reyou’re goinggoing toto havehave toto standstand outout Forget driving to Birmingham to shop for your favorite brands - WaterMark Place Outlet Center has all the brands you want to look your best this Fall - all at an average of 40% off the typical retail price. Score this season’s hottest looks without waiting for a sale! All the fashion at about half the price. GAMEDAY ■ Friday, April 20, 2007 1 ON THE INSIDE ON THE COVER Photo feature On the cover is Alabama Football Take a look back at the arrival of head coach Nick Saban, the new Crimson Tide head coach Nick Crimson Tide leader. Saban to the UA campus. Saban’s arrival at the Capstone on Pages 2-3 Jan. 4 brought a great deal of excite- ment to Tuscaloosa and the state. After going through offseason workouts and spring training under Saban’s leadership, fans look to A- Day to serve as a showcase for what Tracking progress they can expect during the 2007 sea- After the offseason training and son as they get a glimpse of Saban’s spring practice, catch up with how offense, defense and sideline man- the Tide is faring under its new ner for the first time. head coach. In this special A-Day GameDay Pages 4-5 edition, the staff of The Crimson White gives you all the details of the on and off the field Alabama Football happenings. -

Annual Report 2012-2013

DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS ANNUAL REPORT 2012-2013 2012-13 COVERS_AthleticsAnnualReport-FINAL.indd 2 6/28/2013 12:32:46 PM 3 INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS 2012-13 COVERS_AthleticsAnnualReport-FINAL.indd 3 6/28/2013 12:32:49 PM CONTENTS A Letter from the Director …………………………………………………………………… 2 Men’s Tennis ………………………………………………………………………………44 Intercollegiate Athletics Committee ……………………………………………………… 3 Women’s Tennis …………………………………………………………………………46 Remembering Mal Moore ……………………………………………………………………… 4 Volleyball …………………………………………………………………………………48 National Championship Teams ………………………………………………………… 6-11 Athletic Honors ………………………………………………………………………………… 50 Football ……………………………………………………………………………………… 8 2012 Olympics …………………………………………………………………………………… 55 Men’s Golf …………………………………………………………………………………10 Academic Support …………………………………………………………………………… 56 SEC Championship Teams ………………………………………………………………12-15 Academic Honors ……………………………………………………………………………… 58 Football ……………………………………………………………………………………13 Student Welfare ………………………………………………………………………………… 64 Men’s Golf ………………………………………………………………………………… 14 Comunity Outreach …………………………………………………………………………… 66 Women’s Tennis …………………………………………………………………………15 Facilities ………………………………………………………………………………………… 68 Individual Sport Highlights …………………………………………………………… 16-49 Attendance ……………………………………………………………………………………… 70 Baseball ……………………………………………………………………………………16 Marketing and Licensing …………………………………………………………………… 71 Men’s Basketball ………………………………………………………………………18 Media-Athletics Communications ……………………………………………………… 72 Women’s Basketball ……………………………………………………………………20 -

Racism Protest Set Today Games That People Couldn T See and That the "One of the Major Problems Is Convincing Crowds Were Hard to Handle.' Ta Rman Sdid

Racism Protest Set Today games that people couldn t see and that the "One of the major problems is convincing crowds were hard to handle.' Ta rman sdid. certain elements of the black community that "We may not sell standing room tickets at the Penn State wants to help poor kids with an Students Plan Demonstration Maryland game either." Penn State plays its education. " Hodges said. "Yet. I met rec-ruiteis last home football game against Mainland Nov. from out of state who were offering better 15. financial packages than we were. And there arc 1,000 Blacks a lot of schools recruiting now. It's going to During Halftime Program become increasingly competitive." The demonstration is expected to center By STEVE SOLOM ON called racism can be controlled by all people around the small number of black .students The planned demonstration was first Collegian Staff Writer and their institutions." enrolled in the University. Although a precise reported by The Daily Collegian last Tuesday, count has not been made BSU claimed to have The Black Student Union and other stu- In a meeting of the New University Con- . after a meeting of the New Universitv Con counted approximately 400 at registration late ferencc. The story prompted one faculty mem- ference last Monday night , a participating dents not affiliated with BSU will demonstrate in September. University enrollment is 25.000. ber who attended the meeting. Keddie. to warn group in the demonstration Wells Keddie. against "institutional racism" during halftime . The BSU (then the Douglass Association) Collegian reoorter Rena Rosenson not to come of the Penn State-Boston College football game assistant professor of labor studies, said it last January included as one of its "13 de- to the next NUC meeting without a bodyguard. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

2013 - 2014 Media Guide

2013 - 2014 MEDIA GUIDE www.bcsfootball.org The Coaches’ Trophy Each year the winner of the BCS National Champi- onship Game is presented with The Coaches’ Trophy in an on-field ceremony after the game. The current presenting sponsor of the trophy is Dr Pepper. The Coaches’ Trophy is a trademark and copyright image owned by the American Football Coaches As- sociation. It has been awarded to the top team in the Coaches’ Poll since 1986. The USA Today Coaches’ Poll is one of the elements in the BCS Standings. The Trophy — valued at $30,000 — features a foot- ball made of Waterford® Crystal and an ebony base. The winning institution retains The Trophy for perma- nent display on campus. Any portrayal of The Coaches’ Trophy must be li- censed through the AFCA and must clearly indicate the AFCA’s ownership of The Coaches’ Trophy. Specific licensing information and criteria and a his- tory of The Coaches’ Trophy are available at www.championlicensing.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS AFCA Football Coaches’ Trophy ............................................IFC Table of Contents .........................................................................1 BCS Media Contacts/Governance Groups ...............................2-3 Important Dates ...........................................................................4 The 2013-14 Bowl Championship Series ...............................5-11 The BCS Standings ....................................................................12 College Football Playoff .......................................................13-14 -

Volume 109 January 2017

January 2017 Volume 109 January 2017 Dear Parents/Guardians & Students, It feels like only yesterday that I sat in my office one August morning composing my opening of school letter to all of you, welcoming the beginning of a new school year. To realize I sit in that same seat today, reviewing almost an entire semester of school life, feels somewhat surreal. Where the months go I know not; but I am grateful to be doing the journey with you. As we prepare to acknowledge the end of first semester, the holidays move in to overtake us. Nonetheless, it is wise to pause and remind ourselves of the challenges and the rewards we have both faced and felt deeply together, all as a direct result of planning, participation, and partnership. To review them is to know that ours is a high school committed to action and devoted to a drum- beat of activity that brings new meaning to the term “engagement.” Students, parents, and staff are collectively responsible for defining the school we proudly know as Morris Hills High School. The student activities program at Morris Hills High School has been in full motion since the beginning of the 2016 – 2017 school year. The month of September began with the Fall Pep Rally being held on Friday, September 16th. Mr. Harry Fahrer, Teacher of English, introduced each varsity sport to the student body – Girls’ Soccer, Boys’ Soccer, Field Hockey, Volleyball, Cheerleading, Girls’ Cross Country, Boys’ Cross Country, Girls’ Tennis, and Football. Once all the athletes were introduced, members of the student body participated in a series of fun-natured games. -

The Bowl Games

NOTRE DAME THE BOWL GAMES Fullback Jerome Bettis scored two rushing touchdowns and caught a 26-yard pass for a score in Notre Dame’s 28-3 win over Texas A&M in the 1993 Cotton Bowl. (photo by Don Stacy) Bowl Box Scores Notre Dame Bowl Record 1973 SUGAR BOWL Won 13, Lost 12 Notre Dame 24, Alabama 23 December 31, 1973 Season Bowl Opponent W/L Score Alabama came in ranked first in both the Associated Press and United Press International polls with an 11-0 record. Notre Dame came in ranked third according to 1924 Rose (Jan. 1, 1925) Stanford W 27-10 AP and fourth in the UPI poll with a 10-0 record. The Notre Dame victory left the Irish 1969 Cotton (Jan. 1, 1970) Texas L 17-21 first in the AP poll after the bowls, while Alabama dropped to fourth. 1970 Cotton (Jan. 1, 1971) Texas W 24-11 1972 Orange (Jan. 1, 1973) Nebraska L 6-40 1975 ORANGE BOWL 1973 Sugar (Dec. 31, 1973) Alabama W 24-23 Notre Dame 13, Alabama 11 January 1, 1975 1974 Orange (Jan. 1, 1975) Alabama W 13-11 Alabama came in ranked first in the United Press International poll and second in the 1976 Gator (Dec. 27, 1976) Penn State W 20- 9 Associated Press poll with its 11-0 record. Notre Dame came in standing eighth in the 1977 Cotton (Jan. 2, 1978) Texas W 38-10 UPI poll and ninth according to AP with its 9-2 record. The Notre Dame victory left Notre Dame sixth and Alabama fifth in the AP poll after the bowls. -

Football Award Winners

FOOTBALL AWARD WINNERS Consensus All-America Selections 2 Consensus All-Americans by School 20 National Award Winners 32 First Team All-Americans Below FBS 42 NCAA Postgraduate scholarship winners 72 Academic All-America Hall of Fame 81 Academic All-Americans by School 82 CONSENSUS ALL-AMERICA SELECTIONS In 1950, the National Collegiate Athletic Bureau (the NCAA’s service bureau) compiled the first official comprehensive roster of all-time All-Americans. The compilation of the All-America roster was supervised by a panel of analysts working in large part with the historical records contained in the files of the Dr. Baker Football Information Service. The roster consists of only those players who were first-team selections on one or more of the All-America teams that were selected for the national audience and received nationwide circulation. Not included are the thousands of players who received mention on All-America second or third teams, nor the numerous others who were selected by newspapers or agencies with circulations that were not primarily national and with viewpoints, therefore, that were not normally nationwide in scope. The following chart indicates, by year (in left column), which national media and organizations selected All-America teams. The headings at the top of each column refer to the selector (see legend after chart). ALL-AMERICA SELECTORS AA AP C CNN COL CP FBW FC FN FW INS L LIB M N NA NEA SN UP UPI W WCF 1889 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – √ – 1890 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – √ – 1891 – – –