Politics, Eugenics, and Yeats's Radio Broadcasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great War in Irish Poetry

Durham E-Theses Creation from conict: The Great War in Irish poetry Brearton, Frances Elizabeth How to cite: Brearton, Frances Elizabeth (1998) Creation from conict: The Great War in Irish poetry, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5042/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Creation from Conflict: The Great War in Irish Poetry The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Frances Elizabeth Brearton Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D Department of English Studies University of Durham January 1998 12 HAY 1998 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the impact of the First World War on the imaginations of six poets - W.B. -

The Political Aspect of Yeats's Plays

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1969 The unlucky country: The political aspect of Yeats's plays. Dorothy Farmiloe University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Farmiloe, Dorothy, "The unlucky country: The political aspect of Yeats's plays." (1969). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6561. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6561 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE UNLUCKY COUNTRY: THE POLITICAL ASPECT OF YEATS'S PLAYS BY DOROTHY FARMILOB A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of English in Partial Fulfilment of the Requir^ents for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario 1969 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EC52744 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

![[Jargon Society]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3505/jargon-society-283505.webp)

[Jargon Society]

OCCASIONAL LIST / BOSTON BOOK FAIR / NOV. 13-15, 2009 JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS 790 Madison Ave, Suite 605 New York, New York 10065 Tel 212-988-8042 Fax 212-988-8044 Email: [email protected] Please visit our website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers These and other books will be available in Booth 314. It is advisable to place any orders during the fair by calling us at 610-637-3531. All books and manuscripts are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. ALGREN, Nelson. Somebody in Boots. 8vo, original terracotta cloth, dust jacket. N.Y.: The Vanguard Press, (1935). First edition of Algren’s rare first book which served as the genesis for A Walk on the Wild Side (1956). Signed by Algren on the title page and additionally inscribed by him at a later date (1978) on the front free endpaper: “For Christine and Robert Liska from Nelson Algren June 1978”. Algren has incorporated a drawing of a cat in his inscription. Nelson Ahlgren Abraham was born in Detroit in 1909, and later adopted a modified form of his Swedish grandfather’s name. He grew up in Chicago, and earned a B.A. in Journalism from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 1931. In 1933, he moved to Texas to find work, and began his literary career living in a derelict gas station. A short story, “So Help Me”, was accepted by Story magazine and led to an advance of $100.00 for his first book. -

SNL05-NLI WINTER 06.Indd

NEWS Number 26: Winter 2006 2006 marked the centenary of the death of the Norwegian poet and playwright Henrik Ibsen. In September, the Library, along with cultural institutions in many countries around the world participated in the international centenary celebration of this hugely influential writer with a number of Ibsen-related events including Portraits of Ibsen, an exhibition of a series of 46 oil paintings by Haakon Gullvaag, one of Norway’s leading contemporary artists, and Writers in Conversation an event held in the Library’s Seminar Room at which RTÉ broadcaster Myles Dungan interviewed the acclaimed Norwegian writer Lars Saabye Christensen. During both September and October, the Library hosted a series of lunchtime readings by the Dublin Lyric Players exploring themes in Ibsen’s writings, and drawing on his Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann poetry and prose as well as his plays. A series of lunchtime lectures looked at Ibsen’s influence on Irish writers and his impact upon aspects of the Irish Revival. National Library of Ireland The Portraits of Ibsen exhibition coincided with the 4-day State Visit to Ireland by Their Majesties King Harald V and Queen Sonja of Norway. On 19 September, Her Majesty Queen Sonja visited the Library to officially open the Portraits of Ibsen NUACHT exhibition, to visit Yeats: the life and works of William Butler Yeats and also to view a number of Ibsen-related exhibits from the Library’s collections; these included The Quintessence of Ibsenism by George Bernard Shaw (1891), Ibsen’s New Drama by James Joyce (1900); Padraic Colum’s copy of the Prose Dramas of Ibsen, given as a gift to WB Yeats, and various playbills for Dublin performances of Ibsen. -

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems Compiled by Emma Laybourn 2018 This is a free ebook from www.englishliteratureebooks.com It may be shared or copied for any non-commercial purpose. It may not be sold. Cover picture shows Ben Bulben, County Sligo, Ireland. Contents To return to the Contents list at any time, click on the arrow ↑ before each poem. Introduction From The Wanderings of Oisin and other poems (1889) The Song of the Happy Shepherd The Indian upon God The Indian to his Love The Stolen Child Down by the Salley Gardens The Ballad of Moll Magee The Wanderings of Oisin (extracts) From The Rose (1893) To the Rose upon the Rood of Time Fergus and the Druid The Rose of the World The Rose of Battle A Faery Song The Lake Isle of Innisfree The Sorrow of Love When You are Old Who goes with Fergus? The Man who dreamed of Faeryland The Ballad of Father Gilligan The Two Trees From The Wind Among the Reeds (1899) The Lover tells of the Rose in his Heart The Host of the Air The Unappeasable Host The Song of Wandering Aengus The Lover mourns for the Loss of Love He mourns for the Change that has come upon Him and his Beloved, and longs for the End of the World He remembers Forgotten Beauty The Cap and Bells The Valley of the Black Pig The Secret Rose The Travail of Passion The Poet pleads with the Elemental Powers He wishes his Beloved were Dead He wishes for the Cloths of Heaven From In the Seven Woods (1904) In the Seven Woods The Folly of being Comforted Never Give All the Heart The Withering of the Boughs Adam’s Curse Red Hanrahan’s Song about Ireland -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

1 Introduction the Empire at the End of Decadence the Social, Scientific

1 Introduction The Empire at the End of Decadence The social, scientific and industrial revolutions of the later nineteenth century brought with them a ferment of new artistic visions. An emphasis on scientific determinism and the depiction of reality led to the aesthetic movement known as Naturalism, which allowed the human condition to be presented in detached, objective terms, often with a minimum of moral judgment. This in turn was counterbalanced by more metaphorical modes of expression such as Symbolism, Decadence, and Aestheticism, which flourished in both literature and the visual arts, and tended to exalt subjective individual experience at the expense of straightforward depictions of nature and reality. Dismay at the fast pace of social and technological innovation led many adherents of these less realistic movements to reject faith in the new beginnings proclaimed by the voices of progress, and instead focus in an almost perverse way on the imagery of degeneration, artificiality, and ruin. By the 1890s, the provocative, anti-traditionalist attitudes of those writers and artists who had come to be called Decadents, combined with their often bizarre personal habits, had inspired the name for an age that was fascinated by the contemplation of both sumptuousness and demise: the fin de siècle. These artistic and social visions of degeneration and death derived from a variety of inspirations. The pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), who had envisioned human existence as a miserable round of unsatisfied needs and desires that might only be alleviated by the contemplation of works of art or the annihilation of the self, contributed much to fin-de-siècle consciousness.1 Another significant influence may be found in the numerous writers and artists whose works served to link the themes and imagery of Romanticism 2 with those of Symbolism and the fin-de-siècle evocations of Decadence, such as William Blake, Edgar Allen Poe, Eugène Delacroix, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Charles Baudelaire, and Gustave Flaubert. -

Shirt Movements in Interwar Europe: a Totalitarian Fashion

Ler História | 72 | 2018 | pp. 151-173 SHIRT MOVEMENTS IN INTERWAR EUROPE: A TOTALITARIAN FASHION Juan Francisco Fuentes 151 Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain [email protected] The article deals with a typical phenomenon of the interwar period: the proliferation of socio-political movements expressing their “mood” and identity via a paramilitary uniform mainly composed of a coloured shirt. The analysis of 34 European shirt movements reveals some common features in terms of colour, ideology and chronology. Most of them were consistent with the logic and imagery of interwar totalitarianisms, which emerged as an alleged alternative to the decaying bourgeois society and its main political creation: the Parliamentary system. Unlike liBeral pluralism and its institutional expression, shirt move- ments embody the idea of a homogeneous community, based on a racial, social or cultural identity, and defend the streets, not the Ballot Boxes, as a new source of legitimacy. They perfectly mirror the overwhelming presence of the “brutalization of politics” (Mosse) and “senso-propaganda” (Chakhotin) in interwar Europe. Keywords: fascism, Nazism, totalitarianism, shirt movements, interwar period. Resumo (PT) no final do artigo. Résumé (FR) en fin d’article. “Of all items of clothing, shirts are the most important from a politi- cal point of view”, Eugenio Xammar, Berlin correspondent of the Spanish newspaper Ahora, wrote in 1932 (2005b, 74). The ability of the body and clothing to sublimate, to conceal or to express the intentions of a political actor was by no means a discovery of interwar totalitarianisms. Antoine de Baecque studied the political dimension of the body as metaphor in eighteenth-century France, paying special attention to the three specific func- tions that it played in the transition from the Ancien Régime to revolutionary France: embodying the state, narrating history and peopling ceremonies. -

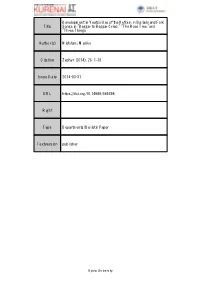

Development in Yeats's Use of the Refrain in Ballads and Folk Title Songs in "Beggar to Beggar Cried," "The Rose Tree,"And "Three Things

Development in Yeats's Use of the Refrain in Ballads and Folk Title Songs in "Beggar to Beggar Cried," "The Rose Tree,"and "Three Things Author(s) Nishitani, Mariko Citation Zephyr (2014), 26: 1-18 Issue Date 2014-03-31 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/189398 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Development in Yeats’s Use of the Refrain in Ballads and Folk Songs in “Beggar to Beggar Cried,” “The Rose Tree,” and “Three Things” Mariko Nishitani Introduction Yeats used the refrain throughout his lifetime and developed its functions at different stages in his career. Although the refrain was an important device for him in many senses, with some exceptions, he rarely referred to it in his prose. The following is one of these exceptions. Here, he explains how a simple repetitive phrase invites an audience to participate in a performance of poetry: In a short poem he [the reciter] may interrupt the narrative with a burden, which the audience will soon learn to sing, and this burden, because it is repeated and need not tell a story to a first hearing, can have a more elaborate musical notation, can go nearer to ordinary song…. (The Irish Dramatic Movement p. 103) The quotation refers to two important aspects of the refrain that would have occupied his mind at that time. First, the refrain in ballads and songs has been associated with establishing a cooperative relationship between a singer and his audience, as well as a sense of unity the singer may share with a singing audience. -

Moreau's Materiality: Polymorphic Subjects, Degeneration, and Physicality Mary C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Moreau's Materiality: Polymorphic Subjects, Degeneration, and Physicality Mary C. Slavkin Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE MOREAU’S MATERIALITY: POLYMORPHIC SUBJECTS, DEGENERATION, AND PHYSICALITY By MARY C. SLAVKIN A Thesis submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The Members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Mary Slavkin defended on March 30, 2009. ___________________________ Lauren Weingarden Professor Directing Thesis ___________________________ Richard Emmerson Committee Member ___________________________ Adam Jolles Committee Member Approved: _______________________________________________ Richard Emmerson, Chair, Department of Art History _______________________________________________ Sally McRorie, Dean, College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For David. Thanks for all the tea. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES..........................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.....................................................................................................................ix CHAPTER 1: Introduction...............................................................................................1 -

Politics in Western Europe Stckholm

Politics in Western Europe Stckholm London Berlin Brussels Paris Rome Politics in Western Europe SECOND EDITION An Introduction to the Politics of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, and the European Union. M. Donald Hancock Vanderbilt University David P. Conradt East Carolina University B. Guy Peters University of Pittsburgh William Safran University of Colorado, Boulder Raphael Zariski University of Nebraska, Lincoln MACMILLAN © Chatham House Publishers, Inc. 1993, 1998 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WIP 9HE. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their right to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First edition 1993 Second edition 1998 Published by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-0-333-69893-8 ISBN 978-1-349-14555-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-14555-3 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling. 10 9 987654321 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 98 Contents List of Tables vii List of Figures xi Preface xiii Introduction xv Part One: The United Kingdom B. -

Irish Political and Public Reactions to the Spanish Civil War

Neutral Ireland? Irish Political and Public Reactions to the Spanish Civil War Lili ZÁCH University of Szeged The Spanish Civil War is considered to be one of the most significant events in the in- ter-war period. Interestingly, the events between 1936 and 1939 reflect not only the for- mulation of power politics in Europe, but also the aims of the Irish1 government in diplo- matic terms. Irish participation in the Spanish Civil War attracted considerable attention recently. However, the Iberian events were not given primary importance in the history of Irish foreign policy. Anglo-Irish relations and the concept of Irish neutrality during and after the Second World War have been the key issues. Although it is a well-known fact in Irish historical circles that the overwhelming majority of the Irish population was support- ing Franco because of religious reasons, other aspects such as the Irish government's ad- herence to non-intervention and the motivations behind it are mostly ignored. So I am inclined to think that it is worth examining the Irish reaction to the Spanish Civil War in its entirety; that is, paying attention to the curiosity of non-intervention as well. This is more than interesting as the "Irishmen were not, as yet, intervening in Spain; but few were neutral."2 In order to provide an insight into Irish public opinion, I based my research partly on the reports of contemporary Dublin-centred Irish daily newspapers, namely the 'conserva- tive' Irish Independent, the 'republican' Irish Press and the 'liberal' Irish Times. All three took different stands on the Spanish Civil War.