Putting Numbers to Feelings: Intellectual Property Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Investigation No. 337-TA-1216]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0446/investigation-no-337-ta-1216-420446.webp)

Investigation No. 337-TA-1216]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 09/03/2020 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2020-19465, and on govinfo.gov 7020-02 INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION [Investigation No. 337-TA-1216] Certain Vacuum Insulated Flasks and Components Thereof; Institution of Investigation AGENCY: U.S. International Trade Commission. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: Notice is hereby given that a complaint was filed with the U.S. International Trade Commission on July 29, 2020, under section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended, on behalf of Steel Technology, LLC d/b/a Hydro Flask of Bend, Oregon and Helen of Troy Limited of El Paso, Texas. A supplement was filed on August 18, 2020. The complaint, as supplemented, alleges violations of section 337 based upon the importation into the United States, the sale for importation, and the sale within the United States after importation of certain vacuum insulated flasks and components thereof by reason of infringement of: (1) the sole claims of U.S. Design Patent No. D806,468 (“the ’468 patent”); U.S. Design Patent No. D786,012 (“the ’012 patent”); U.S. Design Patent No. D799,320 (“the ’320 patent”); and (2) U.S. Trademark Registration No. 4,055,784 (“the ’784 trademark”); U.S. Trademark Registration No. 5,295,365 (“the ’365 trademark”); U.S. Trademark Registration No. 5,176,888 (“the ’888 trademark”); and U.S. Trademark Registration No. 4,806,282 (“the ’282 trademark”). The complaint further alleges that an industry in the United States exists as required by the applicable Federal Statute. -

Sport Industry in Rural China

2018 4th International Conference on Social Science and Management (ICSSM 2018) ISBN: 978-1-60595-190-4 Sport Industry in Rural China: Development Momentum, Characteristics, and Strategy: A Field Study of the City of Jinhua, Zhejiang Province Yun-Xia DING Physical Department, Zhejiang College of Sports, Hangzhou, 311231, Zhejiang Province, China [email protected] Keywords: Sports; Revitalize rural areas; China. Abstract. This paper takes ten sports characteristic villages in Jinhua of Zhejiang province as the research object, uses the scientific research methods such as literature and field follow-up investigation, analyzes the present situation of the sports development of these villages, and then puts forward the concept of the sports village. The paper holds that the sports characteristic village has distinct features such as cultural inheritance, resource dependence, content difference and fusion innovation. The inherent development needs, the natural and cultural environment, the dynamic choice of urban tourists and the government's support policies are the formation and development forces of sports characteristics villages. There remains dilemmas in the case such as the top design is not enough, the theoretical system is not existing, industrial structure is convergent, characteristics advantages are not obvious. We suggest the government to strengthen the scientific and standardized layout, to seek accurate development orientation, to emphasize the center of sports services as well as to explore special lines of sports characteristic villages on space diffusion patterns and laws. Introduction The function of sports in China has witnessed multiple shifts in different historical contexts. Over the past decades, it has been utilized to elevate China's international standing, improve the national physical fitness, and rejuvenate Chinese ethos. -

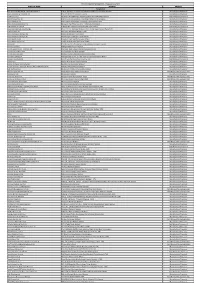

TIER2 SITE NAME ADDRESS PROCESS M Ns Garments Printing & Embroidery

TIER 2 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced July 2021 TIER2 SITE NAME ADDRESS PROCESS Bangladesh Mns Garments Printing & Embroidery (Unit 2) House 305 Road 34 Hazirpukur Choydana National University Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor (A&E) American & Efird (Bd) Ltd Plot 659 & 660 93 Islampur Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor A G Dresses Ltd Ag Tower Plot 09 Block C Tongi Industrial Area Himardighi Gazipur Next Branded Component Abanti Colour Tex Ltd Plot S A 646 Shashongaon Enayetnagar Fatullah Narayanganj Manufacturer/Processor Aboni Knitwear Ltd Plot 169 171 Tetulzhora Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka 1340 Manufacturer/Processor Afrah Washing Industries Ltd Maizpara Taxi Track Area Pan - 4 Patenga Chottogram Manufacturer/Processor AKM Knit Wear Limited Holding No 14 Gedda Cornopara Ulail Savar Dhaka Next Branded Component Aleya Embroidery & Aleya Design Hose 40 Plot 808 Iqbal Bhaban Dhour Nishat Nagar Turag Dhaka 1230 Manufacturer/Processor Alim Knit (Bd) Ltd Nayapara Kashimpur Gazipur 1750 Manufacturer/Processor Aman Fashions & Designs Ltd Nalam Mirzanagar Asulia Savar Manufacturer/Processor Aman Graphics & Design Ltd Nazimnagar Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Aman Sweaters Ltd Rajaghat Road Rajfulbaria Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Aman Winter Wears Ltd Singair Road Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Amann Bd Plot No Rs 2497-98 Tapirbari Tengra Mawna Shreepur Gazipur Next Branded Component Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor Ananta Apparels Ltd - Adamjee Epz Plot 246 - 249 Adamjee Epz Narayanganj -

Annual Report 2019

HAITONG SECURITIES CO., LTD. 海通證券股份有限公司 Annual Report 2019 2019 年度報告 2019 年度報告 Annual Report CONTENTS Section I DEFINITIONS AND MATERIAL RISK WARNINGS 4 Section II COMPANY PROFILE AND KEY FINANCIAL INDICATORS 8 Section III SUMMARY OF THE COMPANY’S BUSINESS 25 Section IV REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 33 Section V SIGNIFICANT EVENTS 85 Section VI CHANGES IN ORDINARY SHARES AND PARTICULARS ABOUT SHAREHOLDERS 123 Section VII PREFERENCE SHARES 134 Section VIII DIRECTORS, SUPERVISORS, SENIOR MANAGEMENT AND EMPLOYEES 135 Section IX CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 191 Section X CORPORATE BONDS 233 Section XI FINANCIAL REPORT 242 Section XII DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE FOR INSPECTION 243 Section XIII INFORMATION DISCLOSURES OF SECURITIES COMPANY 244 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Board, the Supervisory Committee, Directors, Supervisors and senior management of the Company warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of contents of this annual report (the “Report”) and that there is no false representation, misleading statement contained herein or material omission from this Report, for which they will assume joint and several liabilities. This Report was considered and approved at the seventh meeting of the seventh session of the Board. All the Directors of the Company attended the Board meeting. None of the Directors or Supervisors has made any objection to this Report. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu and Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Certified Public Accountants LLP (Special General Partnership)) have audited the annual financial reports of the Company prepared in accordance with PRC GAAP and IFRS respectively, and issued a standard and unqualified audit report of the Company. All financial data in this Report are denominated in RMB unless otherwise indicated. -

20200316 Factory List.Xlsx

Country Factory Name Address BANGLADESH AMAN WINTER WEARS LTD. SINGAIR ROAD, HEMAYETPUR, SAVAR, DHAKA.,0,DHAKA,0,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH KDS GARMENTS IND. LTD. 255, NASIRABAD I/A, BAIZID BOSTAMI ROAD,,,CHITTAGONG-4211,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH DENITEX LIMITED 9/1,KORNOPARA, SAVAR, DHAKA-1340,,DHAKA,,BANGLADESH JAMIRDIA, DUBALIAPARA, VALUKA, MYMENSHINGH BANGLADESH PIONEER KNITWEARS (BD) LTD 2240,,MYMENSHINGH,DHAKA,BANGLADESH PLOT # 49-52, SECTOR # 08 , CEPZ, CHITTAGONG, BANGLADESH HKD INTERNATIONAL (CEPZ) LTD BANGLADESH,,CHITTAGONG,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH FLAXEN DRESS MAKER LTD MEGHDUBI, WARD: 40, GAZIPUR CITY CORP,,,GAZIPUR,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH NETWORK CLOTHING LTD 228/3,SHAHID RAWSHAN SARAK, CHANDANA,,,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH 521/1 GACHA ROAD, BOROBARI,GAZIPUR CITY BANGLADESH ABA FASHIONS LTD CORPORATION,,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH VILLAGE- AMTOIL, P.O. HAT AMTOIL, P.S. SREEPUR, DISTRICT- BANGLADESH SAN APPARELS LTD MAGURA,,JESSORE,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH TASNIAH FABRICS LTD KASHIMPUR NAYAPARA, GAZIPUR SADAR,,GAZIPUR,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH CHERRY INTIMATE LTD PLOT # 105 01,DEPZ, ASHULIA, SAVAR,DHAKA,DHAKA,BANGLADESH COLOMESSHOR, POST OFFICE-NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD SADAR,,,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH VILLAGE-JOYPURA, UNION-SHOMBAG,,UPAZILA-DHAMRAI, BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD DISTRICT,DHAKA,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH VINTAGE DENIM APPARELS LIMITED BOHERARCHALA , SREEPUR,,,GAZIPUR,,BANGLADESH BANGLADESH KDS IDR LTD CDA PLOT NO: 15(P),16,MOHORA -

CHINA DAILY for Chinese and Global Markets

OLD MOBILES CHANCE RELATIONS LOTUS FROM SPACE Outlining the high stakes Flower seeds made Showroom opening to attract > p13 in future China-US ties a tour beyond Earth buyers of hand-assembled cars > ACROSS AMERICA, PAGE 2 > CHINA, PAGE 7 WEDNESDAY, June 19, 2013 chinadailyusa.com $1 The ‘Long March’ to Tinseltown By LIU WEI in shanghai “It is a long way to go,” he [email protected] says, “but I believe as the Chi- nese = lm market keeps growing The next Kung Fu Panda so fast, it is totally possible that will be the brainchild of both Chinese capital will hold shares American and Chinese film- in the major six Hollywood stu- makers and production will dios. It is just a matter of time.” start in August, says Peter Li, China’s Wanda Cultural managing director of China Group is one of the pioneers Media Capital, co-investor of in this process. In 2012 Wanda Oriental DreamWorks, a joint acquired AMC, the second venture with DreamWorks largest theater chain in North Animation. America, for $2.6 billion. CMC co-founded Oriental What Ye Ning, the group’s DreamWorks in 2012 with vice-president, has learned DreamWorks, Shanghai Media from the following integration Group and Shanghai Alliance is, = rst of all, trust and respect. Investment, with the aim of “The managing team of CHARACTER BUILDING producing and distributing ani- AMC was worried that we mated and live-action content would send a group of yellow PHOTO BY SUN CHENBEI / CHINA DAILY for Chinese and global markets. faces to replace them,” Ye says, From le : Li Xiaolin, president -

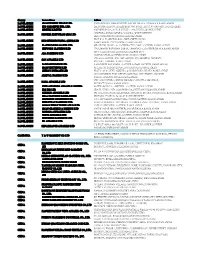

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

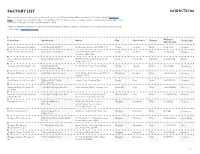

Factory List

FACTORY LIST Our commitment to transparency is core to our Corporate Social Responsibility efforts. Nordstrom’s Tier 1 factory list for Nordstrom Made, our family of private-label brands, is included below. This list reflects our most strategic suppliers, which we classify internally as Level 1 and Level 2. The data is current as of December 11, 2020. Additional information about our commitment to human rights, including our goals for ethical labor practices and women’s empowerment, can be found on nordstromcares.com. Factory Name Manufacturer Address City State/Province Country Employees Product Type (Male/Female) Industria de Calcados Karlitos Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Benedito Merlino, 999, 14405-448 Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 146 (62/84) Footwear Industria de Calcados Kissol Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Irmãos Antunes, 813, Jardim Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 196 (137/59) Footwear Guanabara, 14405-445 Eminent Garment (Cambodia) Eminent Garment Limited Phum Preak Thmey, Khum Teukvil, Srok Saang Khet Kandal Cambodia 866 (105/761) Woven Limited Saang, Phnom Penh Zhejiang Sunmans Knitting Co. Ltd. Royal Bermuda LLC No. 139 North of Biyun Road, 314400 Haining Zhejiang China 197 (39/158) Accessories West Coast Hosiery Group Dongguan Mayflower Footwear Corp. Pagoda International Footwear Golden Dragon Road, 1st Industrial Park of Dongcheng Dongguan China 500 (350/150) Footwear Sangyuan, 523119 Fujian Fuqing Huatai Footwear Co. Madden Intl. Ltd. Trading Lingjiao Village, Shangjing Town Fuqing Fujian China 360 (170/190) Footwear Ltd. Dolce Vita Intl. Nanyuan Knitting & Garments Co. South Asia Knitting Factory Ltd. Nanhua Industry District, Shengxin Town Nanan City Fujian China 604 (152/452) Sweaters Ltd. -

CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 2202)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2202) 2019 ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors (the “Board”) of China Vanke Co., Ltd.* (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 December 2019. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2019 Annual Report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcement of annual results. Printed version of the Company’s 2019 Annual Report will be delivered to the H-Share Holders of the Company and available for viewing on the websites of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk) and of the Company (www.vanke.com) in April 2020. Both the Chinese and English versions of this results announcement are available on the websites of the Company (www.vanke.com) and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk). In the event of any discrepancies in interpretations between the English version and Chinese version, the Chinese version shall prevail, except for the financial report prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards, of which the English version shall prevail. -

Interim Report 2019

INTERIM REPORT 2019 2019 INTERIM REPORT www.cs.ecitic.com I M P O R T A N T N O T I C E The Board and the Supervisory Committee of the Company and the Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of contents of this interim report and that there is no false representation, misleading statement contained herein or material omission from this interim report, for which they will assume joint and several liabilities. This interim report was considered and approved at the 44th Meeting of the Sixth Session of the Board. All Directors attended the meeting. No Director raised any objection to this interim report. The 2019 interim financial statements of the Company were unaudited. PricewaterhouseCoopers Zhong Tian LLP and PricewaterhouseCoopers issued review opinions in accordance with the China and international review standards, respectively. Mr. ZHANG Youjun, head of the Company, Mr. LI Jiong, the person-in-charge of accounting affairs and Ms. KANG Jiang, head of the Company’s accounting department, warrant that the financial statements set out in this interim report are true, accurate and complete. There was no profit distribution plan or plan of conversion of the capital reserve into the share capital of the Company for the first half of 2019. Forward looking statements, including future plans and development strategies, contained in this interim report do not constitute a substantive commitment to investors by the Company. Investors should be aware of investment risks. There was no appropriation of funds of the Company by the related/connected parties for non-operating purposes. -

The 3Rd Party Certificate of FDA Medical Device Registration Note: This File Is Not Being Issued by FDA

The 3rd Party Certificate of FDA Medical Device Registration Note: This file is Not being issued by FDA. We, SFT, as the 3rd party, produce it, intended to facilitate customer display & transmit information. The following contents, FDA registered Facility/Owner/Operator&FDA listing Medical Device, are excerpted from database at www.fda.gov. Establishment: ZHEJIANG STAGE LEATHER APPAREL CO., LTD Jinxi Economic Development Zone, Tangxi Town ,Wucheng District ,Jinhua ,Zhejiang Province.CHINA 310000 Registration Number / FEI Number*: * Firm Establishment Identifier (FEI) should be used for identification of entities within the imports message set Status: Active Date of Registration Status: 2020 Owner/Operator ZHEJIANG STAGE LEATHER APPAREL CO., LTD Jinxi Economic Development Zone, Tangxi Town ,Wucheng District ,Jinhua ,Zhejiang Province.CHINA 310000 Owner/Operator Number: 10062956 Official Correspondent Contact Name: LIE JU MANAGER Jinxi Economic Development Zone, Tangxi Town ,Wucheng District ,Jinhua ,Zhejiang Province.CHINA 310000 Tel: +86-571-85305236 E-mail: [email protected] U.S. Agent Contact Name: Grace Liu Address: 839 FM 1489 Road, Brookshire, Texas 77423 U.S.A Phone: (281) 600-8227 E-mail: [email protected] Devices Listing Information Product Device Listing Establishment Proprietary Name Codes Class Number Operations Mask LYU 1 D374956 Manufacturer MEDICAL PROTECTIVE OEA 1 D374957 Manufacturer OVERBOOT PROTECTIVE CLOTHING OEA 1 D374957 Manufacturer Please careful protect your Listing Number. Approved by: Reilly Professional FDA Registration Services, by Shanghai Shifu Testing Service Co., Ltd. More details on the website: http://www.sft-lab.com. Need help? Contact us, SFT, at +86(021) 51300821&[email protected] FDA CERTIFICATE NUM: SFT20MAR021C . -

![Directors, Supervisors and Parties Involved in the [Redacted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3590/directors-supervisors-and-parties-involved-in-the-redacted-1793590.webp)

Directors, Supervisors and Parties Involved in the [Redacted]

THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THAT THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT. DIRECTORS, SUPERVISORS AND PARTIES INVOLVED IN THE [REDACTED] DIRECTORS Executive Directors Name Residential Address Nationality Mr. Sun Lianqing (孫連清) Room 3, Building E9 Chinese Paris City Versailles Jiaxing Zhejiang Province The PRC Mr. Xu Songqiang (徐松強) Room 206, Building A20 Chinese Dahua City Garden Nanhu District Jiaxing Zhejiang Province The PRC Non-executive Directors Name Residential Address Nationality Mr. He Yujian (何宇健) Room 203, Building 4 Chinese Haiyi Jiayuan Nanhu District Jiaxing Zhejiang Province The PRC Mr. Zheng Huanli (鄭歡利) Room 1005, Building 4 Chinese Zhongshan Mingdu Nanhu District Jiaxing Zhejiang Province The PRC Mr. Fu Songquan (傅松權) No. 278 Yucun Chinese Diankou Town Zhuji City Shaoxing Zhejiang Province The PRC –68– THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THAT THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT. DIRECTORS, SUPERVISORS AND PARTIES INVOLVED IN THE [REDACTED] Independent non-executive Directors Name Residential Address Nationality Mr. Xu Linde (徐林德) Room 2001, Building 9 Chinese Lanjiangyuan Tulip Bank Garden Wenyan Street Xiaoshan District Hangzhou City The PRC Mr. Yu Youda (于友達) Room 302, Unit 2 Chinese Building 12 Liuheyuan Shangcheng District Hangzhou City The PRC Mr. Cheng Hok Kai Frederick Flat C, 12th Floor British (鄭學啟) 10 Lai Wan Road Mei Foo Sun Chuen Kowloon Hong Kong SUPERVISORS Name Residential Address Nationality Ms. Liu Wen (劉雯) Room 302, Building 2 Chinese Tianxing Lake Apartment Nanhu District Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province The PRC Ms.