Its Effects on the Operations of Local Authorities. a Thebis Prepared for MA Degree in P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary

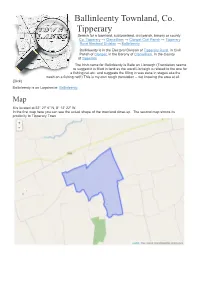

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary Search for a townland, subtownland, civil parish, barony or countySearch Co. Tipperary → Clanwilliam → Clonpet Civil Parish → Tipperary Rural Electoral Division → Ballinleenty Ballinleenty is in the Electoral Division of Tipperary Rural, in Civil Parish of Clonpet, in the Barony of Clanwilliam, in the County of Tipperary The Irish name for Ballinleenty is Baile an Líontaigh (Translation seems to suggest it is filled in land as the word Líontaigh is related to the one for a fishing net etc. and suggests the filling in was done in stages aka the mesh on a fishing net!!) This is my own rough translation – not knowing the area at all. (Dick) Ballinleenty is on Logainm.ie: Ballinleenty. Map It is located at 52° 27' 6" N, 8° 12' 22" W. In the first map here you can see the actual shape of the townland close-up. The second map shows its proximity to Tipperary Town Leaflet | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors Area Ballinleenty has an area of: 1,513,049 m² / 151.30 hectares / 1.5130 km² 0.58 square miles 373.88 acres / 373 acres, 3 roods, 21 perches Nationwide, it is the 17764th largest townland that we know about Within Co. Tipperary, it is the 933rd largest townland Borders Ballinleenty borders the following other townlands: Ardavullane to the west Ardloman to the south Ballynahow to the west Breansha Beg to the east Clonpet to the east Gortagowlane to the north Killea to the south Lackantedane to the east Rathkea to the west Subtownlands We don't know about any subtownlands in Ballinleenty. -

Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to Be Crossed by the Proposed Project

Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to be Crossed by the Proposed Project TB No.: 1 Townlands: Abbotstown/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309268, 238784 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection TB No.: 2 Townlands: Dunsink/ Sheephill Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309327, 238835 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House (within the townland of Sheephill) and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). The remains of a stone demesne wall associated with Abbotstown are located along the northern side of the road (UBH 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection 32102902/EIAR/3B Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 TB No.: 3 Townlands: Sheephill/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 310153, 239339 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south. -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

![County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6319/county-londonderry-official-townlands-administrative-divisions-sorted-by-townland-216319.webp)

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland] Record O.S. Sheet Townland Civil Parish Barony Poor Law Union/ Dispensary /Local District Electoral Division [DED] 1911 D.E.D after c.1921 No. No. Superintendent Registrar's District Registrar's District 1 11, 18 Aghadowey Aghadowey Coleraine Coleraine Aghadowey Aghadowey Aghadowey 2 42 Aghagaskin Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Magherafelt Aghagaskin 3 17 Aghansillagh Balteagh Keenaght Limavady Limavady Lislane Lislane 4 22, 23, 28, 29 Alla Lower Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 5 22, 28 Alla Upper Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 6 28, 29 Altaghoney Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Ballymullins Ballymullins 7 17, 18 Altduff Errigal Coleraine Coleraine Garvagh Glenkeen Glenkeen 8 6 Altibrian Formoyle / Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 9 6 Altikeeragh Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 10 29, 30 Altinure Lower Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 11 29, 30 Altinure Upper Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 12 20 Altnagelvin Clondermot Tirkeeran Londonderry Waterside Rural [Glendermot Waterside Waterside until 1899] 13 41 Annagh and Moneysterlin Desertmartin Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Desertmartin Desertmartin 14 42 Annaghmore Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Bellaghy Castledawson Castledawson 15 48 Annahavil Arboe Loughinsholin Magherafelt Moneymore Moneyhaw -

Report of the Belfast Riots Commissioners

BELFAST BIOTS COMMISSION, 1886. REPOKT 0? THE BELFAST RIOTS COMMISSIONERS. f i-estirftit to Jmisjs of f arliairanf Iijj ®ommait!) of jiei- Stgestj. DUBLIN: PRINTED FOR HER JIAJESTY’s STATIONERY OFFICE, BY ALEXANDER THOM & CO. (Limited), And to be purchased, either directly or through any Bookseller, from Eyre and Spottiswoode, East ITarding-street, Eetter-lane, E.C., or S:i, Abingdon-strcet, Westminster, S.W.; or Adam and Charles Blaok, North Bridge, Edinburgh ; or Hodges, Figgis, and Co., 104, Grafton-street, Dublin. .— 1887 . [0 4925 ,] Price 31 Printed image digitised by the University of Southampton Library Digitisation Unit Printed image digitised by the University of Southampton Library Digitisation Unit — BELFAST RIOTS COMMISSION. EBPOET. TO HIS EXCELLENCY CHAELES STEWART, MARQUESS OF LONDONDERRY, LORD LIEUTENANT-GENERAL AND GENERAL GOVERNOR OF IRELAND. May it please your Excellency, On the 25th day of August, 1886, their Excellencies the then Lords Justices of Ireland, issued their Warrant to four of our number—Sir Edward Bulwer, k.c.b., Frederick Le Poer Trench, q.c., Richard Adams, B.L., and Commander Wallace M'Hardy, b.n., whereby, after reciting that certain riots and disturbances of a serious character had in the months of June, July, and August, 1886, taken place in the borough of Belfast, they authorized and directed us to “inquire into the origin and “ circumstances of the said riots and disturbances, and the cause of their continuance, “ the existing local arrangements for the preservation of the peace of the town “ of -

Download (515Kb)

European Community No. 26/1984 July 10, 1984 Contact: Ella Krucoff (202) 862-9540 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: 1984 ELECTION RESULTS :The newly elected European Parliament - the second to be chosen directly by European voters -- began its five-year term last month with an inaugural session in Strasbourg~ France. The Parliament elected Pierre Pflimlin, a French Christian Democrat, as its new president. Pflimlin, a parliamentarian since 1979, is a former Prime Minister of France and ex-mayor of Strasbourg. Be succeeds Pieter Dankert, a Dutch Socialist, who came in second in the presidential vote this time around. The new assembly quickly exercised one of its major powers -- final say over the European Community budget -- by blocking payment of a L983 budget rebate to the United Kingdom. The rebate had been approved by Community leaders as part of an overall plan to resolve the E.C.'s financial problems. The Parliament froze the rebate after the U.K. opposed a plan for covering a 1984 budget shortfall during a July Council of Ministers meeting. The issue will be discussed again in September by E.C. institutions. Garret FitzGerald, Prime Minister of Ireland, outlined for the Parliament the goals of Ireland's six-month presidency of the E.C. Council. Be urged the representatives to continue working for a more unified Europe in which "free movement of people and goods" is a reality, and he called for more "intensified common action" to fight unemployment. Be said European politicians must work to bolster the public's faith in the E.C., noting that budget problems and inter-governmental "wrangles" have overshadolted the Community's benefits. -

Seanad E´Ireann

Vol. 188 Tuesday, No. 1 11 December 2007 DI´OSPO´ IREACHTAI´ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SEANAD E´ IREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIU´ IL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Tuesday, 11 December 2007. Business of Seanad ………………………………1 Order of Business …………………………………2 Fisheries Orders: Motions………………………………18 Defamation Bill 2006: Committee Stage (resumed)……………………19 Business of Seanad ………………………………56 Defamation Bill 2006: Committee Stage (resumed)……………………57 Adjournment Matter Harbours and Piers ………………………………60 1 2 SEANAD E´ IREANN DI´OSPO´ IREACHTAI´ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES TUAIRISC OIFIGIU´ IL OFFICIAL REPORT Imleabhar 188 Volume 188 De´ Ma´irt, 11 Nollaig 2007. Tuesday, 11 December 2007. ———— Chuaigh an Cathaoirleach i gceannas ar 2.30 p.m. ———— Paidir. Prayer. ———— Business of Seanad. clusion of business. I regret I have had to rule out of order the matter raised by Senator Keaveney An Cathaoirleach: I have received notice from as the Minister has no official responsibly in the Senator Brian O´ Domhnaill that he proposes to matter. It is a matter for the Road Safety Auth- raise the following matter on the Adjournment: ority. I also regret I have had to rule out of order The need for the Minister for Community, the matter raised by Senator McFadden as the Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs to allocate funding Minister has no official responsibility in the to the Inishboffin (Dhun na nGall) pier refur- matter. It is a matter for Iarnro´ dE´ ireann. bishment project and the Tory Island sea wall Before I call on the Leader, I would like to project. welcome to the distinguished members’ gallery former Members of this House, namely, Mary I have also received notice from Senator Cecilia Henry, Michael Brennan, Liam Fitzgerald, Keaveney of the following matter: Kathleen O’Meara, Sheila Terry, Tom Fitzgerald The need for the Minister for Finance to and Brian Mullooly, who is a former Cathaoir- clarify the status of the acquisition of a site in leach. -

Agenda Item No: 6 Committee: Cabinet Date: 20Th February 2020 Report Title: Parish Street Lighting 1. Purpose / Summary to Cons

Agenda Item No: 6 Committee: Cabinet Date: 20th February 2020 Report Title: Parish Street Lighting 1. Purpose / Summary To consider and agree future funding arrangements for Parish Council street lighting 2. Key issues • Footway lighting in the twelve Parish Council areas are owned by the individual Parish Council • Six of the Twelve Parish Councils have entered into a service level agreement with FDC for the repair, management, maintenance and provision of energy for their street lighting assets. • Six of the Parish Councils manage their own street lighting assets and have made, or are in the process of making alternative maintenance and energy arrangements • Currently the Parish Councils fund energy, repairs, maintenance and replacement costs for their own street lights either by FDC contract recharges for those who have entered in to an SLA, or through their own energy and maintenance arrangements. • FDC no longer procures street light energy from the County Council and have entered into a new meter point access number agreement with UKPN. The agreement covers lighting assets owned by the District, Clarion Housing Association and the Six Parish Councils who entered into an FDC SLA in September 2018. • An offer to join the FDC contracts remains for the Six Parish Councils who have left the FDC arrangements subject to various external factors being satisfied. This includes potential renegotiation with the existing contractor, the contract renewal dates and review of the current specifications of the lighting stock which will incur costs. It should be noted that Parish Councils would be able to join both the repairs and maintenance and energy contracts but it is not possible to join the energy scheme only if the Parish Council maintains its own stock. -

![1869.] Local Government Acts Extension. 97 Rick Were Last Year](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7530/1869-local-government-acts-extension-97-rick-were-last-year-407530.webp)

1869.] Local Government Acts Extension. 97 Rick Were Last Year

1869.] Local Government Acts Extension. 97 rick were last year successfully brought under its operations, and as its provisions are better understood, I am confident they will be more generally applied. I do not see any very important distinction between the deepening of a lengthened river course and the construc- tion of a tramway or a railway extension, as far as parliamentary powers are concerned. I have been one of those who confidently asserted many years ago, as I do now, that railways should, in the advance of civilization and scientific improvement, be regarded as nothing more than common highways, differing from them only in cost and carefulness of construction, and the exclusive purposes to which their peculiar characteristics require them to be applied. For these peculiar features the legislature can easily provide, and 1 hope in our time to see their civilizing influences more easily attain- able by the removal of those barriers which now render their adop- tion so costly and so difficult, and that this desirable result will be attained by the total abolition of the present tedious and expensive ordeal of Private Bill Legislation. The limits which the rules of this Society, and regard for the feel- ings of my auditory, impose upon me, have prevented me from going at greater length into this branch of the subject, but I hope I have not trespassed too much on your patience, in attracting your atten- tion to a subject which I feel to be one of the greatest possible im- portance to this part of the United Kingdom. -

Morrison: Essential Public Affairs for Journalists 6E

Morrison: Essential Public Affairs for Journalists 6e CHAPTER 1: THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION AND MONARCHY TABLE 1A MAIN ENTITLEMENTS LISTED IN BILL OF RIGHTS 1689 Freedoms for all ‘Englishmen’ Sanctions for Roman Catholics Freedom from royal interference with the law— Ban on Catholics succeeding to English throne— sovereigns forbidden from establishing their own reflecting the supposed fact that ‘it hath been found courts, or acting as judge themselves by experience that it is inconsistent with the safety and welfare of this protestant kingdom to be governed by a papist prince’ Freedom from being taxed without Parliament’s Obligation on newly crowned sovereigns to swear agreement oaths of allegiance to Church of England Freedom to petition reigning monarch Freedom for Protestants only to possess ‘arms for Bar on carrying weapons defence’ Freedom from drafting into peacetime army without Parliament’s consent Freedom to elect MPs without sovereign’s interference Freedom from cruel and unusual punishments and excessive bail Freedom from fines and forfeitures without trial TABLE 1B RULES GOVERNING MONARCHICAL SUCCESSION IN THE ACT OF SETTLEMENT 1701 Details Protestants only The Crown should pass to Protestant descendants of Electress Sophie of Hanover (first cousin once removed of Queen Anne, who inherited throne after deaths of Mary and William) No marriages to Catholics Monarchs ‘shall join in communion’ with Church of England and not marry Roman Catholics England for the English If anyone not native to England inherits throne, the country will not wage war for ‘any dominions or territories which do not belong to the Crown of England without the consent of Parliament’ Loyalty from the Crown No monarch may leave ‘British Isles’ without Parliament’s consent (repealed by George I in 1716) Openness before Parliament All government matters within Privy Council’s jurisdiction (see p. -

Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999

TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased through any bookseller, or directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2 £12.00 €15.24 © Copyright Government of Ireland 2000 ISBN 0-7076-6434-9 P. 33331/E Gr. 30-01 7/00 3,000 Brunswick Press Ltd. ii CLÁR CONTENTS Page Foreword........................................................................................................................................................................ v Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... vii LOCAL AUTHORITIES County Councils Carlow...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cavan....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Clare ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Cork (Northern Division) .......................................................................................................................................... 19 Cork (Southern Division)......................................................................................................................................... -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Electoral

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Electoral Institutions and Information Shortcuts: The Effect of Decisive Intraparty Competition on the Behavior of Voters and Party Elites A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Melody Ellis Valdini Committee in charge: Professor Matthew Shugart, Chair Professor Lisa Baldez Professor Shaun Bowler Professor Maria Charles Professor Karen Ferree Professor Samuel Popkin 2006 Copyright Melody Ellis Valdini, 2006 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Melody Ellis Valdini is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii DEDICATION In recognition of his never-ending support, generosity, care, and love, this dissertation is dedicated to the sweetest person I’ve ever known, Andy Ellis Valdini. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...............................................................................................................iii Dedication...................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents...........................................................................................................