Personal Cockpits and Sound Capsules the Advent Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early Years of the Acoustic Phonograph Its Developmental Origins and Fall from Favor 1877-1929

THE EARLY YEARS OF THE ACOUSTIC PHONOGRAPH ITS DEVELOPMENTAL ORIGINS AND FALL FROM FAVOR 1877-1929 by CARL R. MC QUEARY A SENIOR THESIS IN HISTORICAL AMERICAN TECHNOLOGIES Submitted to the General Studies Committee of the College of Arts and Sciences of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of BACHELOR OF GENERAL STUDIES Approved Accepted Director of General Studies March, 1990 0^ Ac T 3> ^"^^ DEDICATION No. 2) This thesis would not have been possible without the love and support of my wife Laura, who has continued to love me even when I had phonograph parts scattered through out the house. Thanks also to my loving parents, who have always been there for me. The Early Years of the Acoustic Phonograph Its developmental origins and fall from favor 1877-1929 "Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snov^. And everywhere that Mary went, the lamb was sure to go." With the recitation of a child's nursery rhyme, thirty-year- old Thomas Alva Edison ushered in a bright new age--the age of recorded sound. Edison's successful reproduction and recording of the human voice was the end result of countless hours of work on his part and represented the culmination of mankind's attempts, over thousands of years, to capture and reproduce the sounds and rhythms of his own vocal utterances as well as those of his environment. Although the industry that Edison spawned continues to this day, the phonograph is much changed, and little resembles the simple acoustical marvel that Edison created. -

Wired Presentationpro™ Public Address System PA310 Owner’S Manual

Wired PresentationPro™ Public Address System PA310 Owner’s Manual Shown with optional MB-PA3W wall mounting bracket and TP-30 tripod sold separately califone.com Califone PA310 Rev 01 0214 PA310 PresentationPro™ Owner’s Manual Thank you for purchasing this PresentationPro™ (PA310), the most versatile and portable PA for use in school, business, Houses of Worship and government facilities. We encourage you to visit www.califone.com/registration.php, to register your product for its warranty coverage, to sign up to receive our newsletter, download our catalog, and learn more about the complete line of Califone audio visual products, including portable and installed wireless PA systems, multimedia players and recorders, headphones and headsets, computer peripheral equipment, visual presentation products and language learning materials. Unpacking your PresentationPro™ Contents Inspection and inventory of your system. Check unit carefully a) PA310 Powered Amplifier* for damage that may have occurred during transit. Each PresentationPro™ product is carefully inspected at the b) PI-RC Remote Control and (2) AAA Batteries factory and packed in a special carton for safe transport. c) Quick Start Sheet ALL DAMAGE CLAIMS MUST BE MADE *MB-PA3W mounting bracket sold separately WITH THE FREIGHT CARRIER Notify the freight carrier immediately if you observe any damage the shipping carton or product. Repack the unit in the carton and await inspection by the carrier’s claim agent. Notify your dealer of the pending freight claim. Connections and Functions Warranty Registration NOTE: When first connecting other equipment to “aux in” or “line” in make certain that their power is Please visit the Califone website to register your off and volume control at minimum. -

Loudspeakers and Headphones 21 –24 August 2013 Helsinki, Finland

CONFERENCE REPORT AES 51 st International Conference Loudspeakers and Headphones 21 –24 August 2013 Helsinki, Finland CONFERENCE REPORT elsinki, Finland is known for having two sea - An unexpectedly large turnout of 130 people almost sons: August and winter (adapted from Con - overwhelmed the organizers as over 75% of them Hnolly). However, despite some torrential rain in registered around the time of the “early bird” cut-off the previous week, the weather during the conference date. Twenty countries were represented with most of was excellent. The conference was held at the Helsinki the participants coming from Europe, but some came Congress Paasitorni, which was built in the first from as far away as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Lima, decades of the twentieth century. The recently restored Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, and Guangzhou. Companies building is made of granite that was dug from the such Apple, Beats, Comsol, Bose, Genelec, Harman, ground where the building now stands. The location KEF, Neumann, Nokia, Samsung, Sennheiser, Skype, near the city center and right by the harbor proved to and Sony were represented by their employees. be an excellent location both for transportation and Universities represented included Aalto (in Helsinki), the social program. Aalborg, Budapest, and Kyushu. 790 J. Audio Eng. Soc., Vol. 61, No. 10, 2013 October CONFERENCE REPORT A packed House of Science and Letters for the Tutorial Day Sponsors Juha Backmann insists that “Reproduced audio WILL be better in the future.” J. Audio Eng. Soc., Vol. 61, No. 10, 2013 October 791 CONFERENCE REPORT low-frequency performance can still be designed using Thiele- Small parameters in a simulation, and the effect of individual parameters (such as voice coil length and pole piece size) on the system performance can be seen directly. -

ACCESS for Ells 2.0 Headset Specifications

ACCESS for ELLs 2.0 Headset Specifications The table below outlines features for headsets and recording devices and WIDA’s rationale in recommending those features. Please note that WIDA does not endorse specific brands or devices. Recommended Reason for Recommendation Alternatives not Features Recommended Device: Allows for recording and playback using Separate headphones and Headset the same device. microphone increase the need to ensure proper connection and setup on the computer and thus complicate the testing site set-up. Headset Design: Comfortable when worn for a longer In ear headphones (ear buds) that Over Ear period of time by students of different are placed directly in the ear canal Headphones ages. Weight and size of headphones are more difficult to clean between can be selected based on students’ age. uses by different students. They are Portable headphones are smaller and also not suitable for younger lighter and hence may be suitable for students. Many ear buds come with younger students. Deluxe headphones the microphone attached to the are larger and heavier but have the cord, making capturing the advantage of canceling out more noise. students’ voice more of a challenge. Play Back Mode: The sound files of the assessment are Stereo recorded and played back in stereo. Noise Cancellation Noise cancellation often does not Many headsets with a noise Feature: cancel out the sound of human voices. cancellation feature require a power source (e.g. batteries or USB None connection) and hence complicate the testing site set-up. Type of Connector Some computers have two ports for Many USB-connected headsets Plug: connecting audio-out and audio-in require driver installation, but • Single 3.5 mm separately, while others have one port perform adequately for audio plug (TRRS) for both. -

Headamp 6 Manual

HeadAmp6 PROFESSIONAL SIX CHANNEL HEADPHONE AMPLIFIER OPERATION MANUAL 1 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS – READ FIRST This symbol, wherever it appears, This symbol, wherever it appears, alerts alerts you to the presence of uninsulated you to important operating and maintenance dangerous voltage inside the enclosure. Voltage instructions in the accompanying literature. that may be sufficient to constitute a risk of shock. Please read manual. Read Instructions: Retain these safety and operating instructions for future reference. Heed all warnings printed here and on the equipment. Follow the operating instructions printed in this user guide. Do Not Open: There are no user serviceable parts inside. Refer any service work to qualified technical personnel only. Power Sources: Only connect the unit to mains power of the type marked on the rear panel. The power source must provide a good ground connection. Power Cord: Use the power cord with sealed mains plug appropriate for your local mains supply as provided with the equipment. If the provided plug does not fit into your outlet consult your service agent. Route the power cord so that it is not likely to be walked on, stretched or pinched by items placed upon or against. Grounding: Do not defeat the grounding and polarization means of the power cord plug. Do not remove or tamper with the ground connection on the power cord. Ventilation: Do not obstruct the ventilation slots or position the unit where the air required for ventilation is impeded. If the unit is to be operated in a rack, case or other furniture, ensure that it is constructed to allow adequate ventilation. -

The Lab Notebook

Thomas Edison National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior The Lab Notebook Upcoming Exhibits Will Focus on the Origins of Recorded Sound A new exhibit is coming soon to Building 5 that highlights the work of Thomas Edison’s predecessors in the effort to record sound. The exhibit, accompanied by a detailed web presentation, will explore the work of two French scientists who were pioneers in the field of acoustics. In 1857 Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville invented what he called the phonautograph, a device that traced an image of speech on a glass coated with lampblack, producing a phonautogram. He later changed the recording apparatus to a rotating cylinder and joined with instrument makers to com- mercialize the device. A second Frenchman, Charles Cros, drew inspiration from the telephone and its pair of diaphragms—one that received the speaker’s voice and the second that reconstituted it for the listener. Cros suggested a means of driving a second diaphragm from the tracings of a phonauto- gram, thereby reproducing previously-recorded sound waves. In other words, he conceived of playing back recorded sound. His device was called a paléophone, although he never built one. Despite that, today the French celebrate Cros as the inventor of sound reproduction. Three replicas that will be on display. From left: Scott’s phonautograph, an Edison disc phonograph, and Edison’s 1877 phonograph. Conservation Continues at the Park Workers remove the light The Renova/PARS Environ- fixture outside the front mental Group surveys the door of the Glenmont chemicals in Edison’s desk and home. -

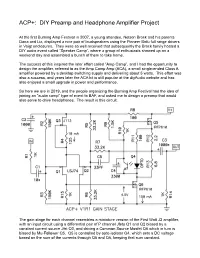

ACP+: DIY Preamp and Headphone Amplifier Project

ACP+: DIY Preamp and Headphone Amplifier Project At the first Burning Amp Festival in 2007, a young attendee, Nelson Brock and his parents Dana and Liz, displayed a nice pair of loudspeakers using the Pioneer Bofu full range drivers in Voigt enclosures. They were so well received that subsequently the Brock family hosted a DIY audio event called “Speaker Camp”, where a group of enthusiasts showed up on a weekend day and assembled a bunch of them to take home. The success of this inspired the later effort called “Amp Camp”, and I had the opportunity to design the amplifier, referred to as the Amp Camp Amp (ACA), a small single-ended Class A amplifier powered by a desktop switching supply and delivering about 5 watts. This effort was also a success, and years later the ACA kit is still popular at the diyAudio website and has also enjoyed a small upgrade in power and performance. So here we are in 2019, and the people organizing the Burning Amp Festival had the idea of joining an “audio camp” type of event to BAF, and asked me to design a preamp that would also serve to drive headphones. The result is this circuit: The gain stage for each channel resembles a miniature version of the First Watt J2 amplifier, with an input circuit using a differential pair of P channel Jfets Q1 and Q2 biased by a constant current source Jfet Q3, and driving a Common Source Mosfet Q6 which in turn is biased by Mu-Follower Q5. Q5 is controlled by opto-isolator Q4, which sets a DC voltage based on the sum of the currents through Q5 and Q6, keeping that sum constant. -

THE DYNAMIC RANGE POTENTIAL of the PHONOGRAPH by Ronald M

THE DYNAMIC RANGE POTENTIAL OF THE PHONOGRAPH By Ronald M. Bauman his article describes a new transmission standards of even lower added to the quietest passages by the approach for analyzing the quality than our current CD standards. cartridge-preamplifier combination dynamic range of the phono- Unless these standards are dramatical- should be essentially inaudible. graphic playback system, in which the ly upgraded (in terms of information Similarly, the cartridge-preamp sys- cartridge and preamplifier are treated content), we may never have a source tem should be able to clearly repro- as an integrated system. I analyzed of music for our homes that sounds ducd the loudest sounds on record the dynamic range potential of several better than the phonograph. without distortion, compression, or combinations of phono cartridges and Are analog records inherently better clipping. preamplifier amplifying devices and in some sense? Your ears may already The same should be true of CD compared the results to CDs. be telling you that analog can sound playback. The quietest passages Additionally, I speculate about the better than today's digital. I will should be reproduced without added drawbacks of frequency domain char- provide quantitative reasons this may noise or distortion of the rnusic acterizations of musical audio compo- be so. caused by amplitude steps, or sam- nents and suggest that the time pling intervals that are too coarse, or domain may be a more natural frame Qualitative Requirements by filter phase shifts and ringing. The of reference for audio instrumentation The subtlety of detail in the grooves of loudest peaks encoded, as for analog development. -

Chapter 186 NOISE

Chapter 186 NOISE §186-1. Loud and unnecessary noise §186-3. Permits for amplifying devices. prohibited. §186-4. Stationary noise limits; maximum §186-2. Loud and unnecessary noises permissible sound levels. enumerated. §186-5. Violations and penalties. [HISTORY: Adopted by the Village Board of the Village of Albany 5-11-1992 as Sec. 11-2- 7 of the 1992 Code. Amendments noted where applicable.] GENERAL REFERENCES Disorderly conduct -- See Ch. 110. Parks and navigable waters -- See Ch. 198, §198-1B(2). Peace and good order -- See Ch. 202. §186-1. Loud and unnecessary noise prohibited. It shall be unlawful for any person to make, continue or cause to be made or continued any loud and unnecessary noise. It shall be unlawful for any person knowingly or wantonly to use or operate, or to cause to be used or operated, any mechanical device, machine, apparatus or instrument for intensification or amplification of the human voice or any sound or noise in any public or private place in such manner that the peace and good order of the neighborhood is disturbed or that persons owning, using or occupying property in the neighborhood are disturbed or annoyed. §186-2. Loud and unnecessary noises enumerated. The following acts are declared to be loud, disturbing and unnecessary noises in violation of this chapter, but this enumeration shall not be deemed to be exclusive: A. Horns; signaling devices. The sounding of any horn or signaling device on any automobile, motorcycle or other vehicle on any street or public place in the village for longer than three seconds in any period of one minute or less, except as a danger warning; the creation of any unreasonable loud or harsh sound by means of any signaling device and the sounding of any plainly audible device for an unreasonable period of time; the use of any signaling device except one operated by hand or electricity; the use of any horn, whistle or other device operated by engine exhaust and the use of any signaling device when traffic is for any reason held up. -

ADI-2 Pro FS R

User’s Guide ADI-2 Pro FS R Conversion done right 32 Bit / 768 kHz Hi-Res Audio SteadyClock FS SyncCheck 2 Channels Analog / Digital Converter 4 Channels Digital / Analog Converter AES / ADAT / SPDIF Interface 32 Bit / 768 kHz Digital Audio USB 2.0 Class Compliant 2 Extreme Power Headphone Outputs Digital Signal Processing Advanced Feature Set Extended Remote Control General 1 Introduction ...............................................................5 2 Package Contents .....................................................5 3 System Requirements ..............................................5 4 Brief Description and Characteristics.....................6 5 First Usage - Quick Start 5.1 Connectors and Controls ........................................7 5.2 Quick Start ..............................................................8 5.3 Operation at the unit................................................8 5.4 Overview Menu Structure .......................................9 5.5 Playback................................................................10 5.6 Analog Recording..................................................10 5.7 Digital Recording...................................................10 6 Power Supply...........................................................11 7 Firmware Update.....................................................11 8 Features Explained 8.1 Extreme Power Headphones Outputs ..................12 8.2 Dual Phones Outputs............................................13 8.3 5-band Parametric EQ ..........................................13 -

Aero Voice™ Airborne Loudhailer Systems

AERO VOICE™ AIRBORNE LOUDHAILER SYSTEMS INSTALLATION & USER’S GUIDE PSAIR12A PSAIR22A PSAIR42A Power Sonix, Inc. 122 S. Church St., Martinsburg, WV 25401 USA 304-267-7560; Fax 304-268-8691 www.powersonix.com TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Overview Of Aero Voice Public Address Systems Page 1 Installation Considerations II. Installation Quick Start & Checklist Page 2 Standard Cable Connections Power For The Aero Voice System DC Power From Aircraft Batteries DC Power From Power Sonix 28 V Auxiliary Battery Pack Audio Controller/Remote Control Unit III. Mounting The Amplified Speaker(s) Page 6 PSAIR12 PSAIR22 PSAIR42 IV. Using The Aero Voice System Page 10 Using the Power Sonix Remote Control Unit Interfacing With Cockpit Audio Controllers Live Microphone Pre-Recorded Messages, Tape/Digital Input Standard Sirens Custom Sirens/Sounds V. Maintenance Page 13 Routine Audio Testing Battery Maintenance & Charging VI. Technical Specifications Page 17 VII. Limited 2-Year Warranty Page 18 RMAs Power Sonix Support VIII. Appendix: Drawings & Illustrations IX. Your Dealer/Outfitter Info: ____________________________________________________ Dealer Sales Contact Phone ____________________________________________________ Dealer Customer Service Contact Phone ____________________________________________________ Outfitter/Installation Service Contact Phone 304-267-7560 ____________________________________________________ Power Sonix Factory Support/RMAs Contact © 2006 Power Sonix, Inc. All rights reserved. Page 1 I. Overview Of Aero Voice Public Address Systems Congratulations on your purchase of a Power Sonix public address system. Your aircraft is about to be equipped with the best performing airborne speech projection system in the world today. No other system is as light, as compact, as intelligible, as powerful or as economical as Power Sonix. The Power Sonix “A” series of Loudhailer Systems was specifically developed for those who wish to recess their speakers and amplifiers inside the aircraft for a flush mount. -

HM-4 Owners Manual

OWNER’S MANUAL POWER PHONES 4 PHONES 3 PHONES 2 PHONES 1 INPUT 1 2 3 4 +12V DC Important Safety Instructions 1. Read these instructions. 13. This device complies with FCC radiation exposure limits set 2. Keep these instructions. forth for an uncontrolled environment. This device should be 3. Heed all warnings. installed and operated with minimum distance 20cm between 4. Follow all instructions. the radiator & your body. 5. Do not use this apparatus near water. 14. This apparatus does not exceed the Class A/Class B 6. Clean only with a dry cloth. (whichever is applicable) limits for radio noise emissions 7. Do not block any ventilation openings. Install in accordance from digital apparatus as set out in the radio interference with the manufacturer’s instructions. regulations of the Canadian Department of Communications. 8. Do not install near any heat sources such as radiators, heat ATTENTION — Le présent appareil numérique n’émet pas de bruits registers, stoves, or other apparatus (including amplifiers) radioélectriques dépassant las limites applicables aux that produce heat. appareils numériques de class A/de class B (selon le cas) 9. Only use attachments/accessories specified by the prescrites dans le réglement sur le brouillage radioélectrique manufacturer. édicté par les ministere des communications du Canada. 10. Refer all servicing to qualified service personnel. Servicing is 15. This device complies with Industry Canada licence-exempt RSS required when the apparatus has been damaged in any way, such standard(s). as power-supply cord or plug is damaged, liquid has been spilled Operation is subject to the following two conditions: or objects have fallen into the apparatus, the apparatus has been (1) this device may not cause interference, and exposed to rain or moisture, does not operate normally, or has (2) this device must accept any interference, including been dropped.