Why the Rabies Vaccine Should Be Approved for Wolfdogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolf Hybrids

Wolf Hybrids By Claudine Wilkins and Jessica Rock, Founders of Animal Law Source™ DEFINITION By definition, the wolf-dog hybrid is a cross between a domestic dog (Canis familiaris) and a wild Wolf (Canis Lupus). Wolves are the evolutionary ancestor of dogs. Dogs evolved from wolves through thousands of years of adaptation, living and being selectively bred and domesticated by humans. Because dogs and wolves are evolutionarily connected, dogs and wolves can breed together. Although this cross breeding can occur naturally, it is a rare occurrence in the wild due to the territorial and aggressive nature of wolves. Recently, the breeding of a dog with a wolf has become an accepted new phenomenon because wolf-hybrids are considered to be exotic and prestigious to own. To circumvent the prohibition against keeping wolves as pets, enterprising people have gone underground and are breeding and selling wolf-dog hybrids in their backyards. Consequently, an increase in the number of hybrids are being possessed without the minimum public safeguards required for the common domestic dog. TRAITS OF DOGS AND WOLVES Since wolf hybrids are a genetic mixture of wolves and dogs, they can seem to be similar on the surface. However, even though both may appear to be physically similar, there are many behavioral differences between wolves and dogs. Wolves raised in the wild appear to fear humans and will avoid contact whenever possible. Wolves raised in captivity are not as fearful of humans. This suggests that such fear may be learned rather than inherited. Dogs, on the other hand, socialize quite readily with humans, often preferring human company to that of other dogs. -

From Wolves to Dogs, and Back: Genetic Composition of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog

RESEARCH ARTICLE From Wolves to Dogs, and Back: Genetic Composition of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog Milena Smetanová1☯, Barbora Černá Bolfíková1☯*, Ettore Randi2,3, Romolo Caniglia2, Elena Fabbri2, Marco Galaverni2, Miroslav Kutal4,5, Pavel Hulva6,7 1 Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Prague, Czech Republic, 2 Laboratorio di Genetica, Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA), Ozzano Emilia (BO), Italy, 3 Department 18/Section of Environmental Engineering, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 4 Institute of Forest Ecology, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Mendel University in Brno, Brno, Czech Republic, 5 Friends of the Earth Czech Republic, Olomouc branch, Olomouc, Czech Republic, 6 Department of Zoology, Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic, 7 Department of Biology and Ecology, Ostrava University, Ostrava, Czech Republic ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS The Czechoslovakian Wolfdog is a unique dog breed that originated from hybridization between German Shepherds and wild Carpathian wolves in the 1950s as a military experi- Citation: Smetanová M, Černá Bolfíková B, Randi E, ment. This breed was used for guarding the Czechoslovakian borders during the cold war Caniglia R, Fabbri E, Galaverni M, et al. (2015) From Wolves to Dogs, and Back: Genetic Composition of and is currently kept by civilian breeders all round the world. The aim of our study was to the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog. PLoS ONE 10(12): characterize, for the first time, the genetic composition of this breed in relation to its known e0143807. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143807 source populations. We sequenced the hypervariable part of the mtDNA control region and Editor: Dan Mishmar, Ben-Gurion University of the genotyped the Amelogenin gene, four sex-linked microsatellites and 39 autosomal micro- Negev, ISRAEL satellites in 79 Czechoslovakian Wolfdogs, 20 German Shepherds and 28 Carpathian Received: July 22, 2015 wolves. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

(HSVMA) Veterinary Report on Puppy Mills May 2013

Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association (HSVMA) Veterinary Report on Puppy Mills May 2013 Puppy mills are large-scale canine commercial breeding establishments (CBEs) where puppies are produced in large numbers and dogs are kept in inhumane conditions for commercial sale. That is, the dog breeding facility keeps so many dogs that the needs of the breeding dogs and puppies are not met sufficiently to provide a reasonably decent quality of life for all of the animals. Although the conditions in CBEs vary widely in quality, puppy mills are typically operated with an emphasis on profits over animal welfare and the dogs often live in substandard conditions, housed for their entire reproductive lives in cages or runs, provided little to no positive human interaction or other forms of environmental enrichment, and minimal to no veterinary care. This report reviews the following: • What Makes a Breeding Facility a “Puppy Mill”? • How are Puppies from Puppy Mills Sold? • How Many Puppies Come from Puppy Mills? • Mill Environment Impact on Dog Health • Common Ailments of Puppies from Puppy Mills • Impact of Resale Process on Puppy Health • How Puppy Buyers are Affected • Impact on Animal Shelters and Other Organizations • Conclusion • References What Makes a Breeding Facility a “Puppy Mill”? Emphasis on Quantity not Quality Puppy mills focus on quantity rather than quality. That is, they concentrate on producing as many puppies as possible to maximize profits, impacting the quality of the puppies that are produced. This leads to extreme overcrowding, with some CBEs housing 1,000+ dogs (often referred to as “mega mills”). When dogs live in overcrowded conditions, diseases spread easily. -

Heartworm Prevention

THE WHOLE STORY ABOUT HEARTWORM (much of which you may not be told otherwise) Notes by Lee Cullens, March 2008 (revised 08/24/08) In memory of Daisy 1997-2007 a beloved companion that suffered because of my ignorance, and blind acceptance of advice from those regarded as knowledgeable. The crucial quality of life decisions are yours alone, and should be based on as much balanced information as can be acquired. Your companion animal can’t speak for itself, it relies on your sense of responsibility for protection. This paper was compiled, in part, because of commercial interest fear tactics, misinformation, and the susceptibility of many to not see beyond such. I suspected there was more to the issue, and believed a more balanced understanding might help other companion animals. This paper is not intended as medical advice, and should not be taken as such. It is simply a compilation of notes from my research to better maintain the health of my own dogs, and is shared for informational purposes only. The idea is to be much better prepared when one does consult with a veterinarian :-) Nor am I asking that you “believe” everything I put forth, but I do hope, for the sake of your companion animals, that you read and understand the contents of this paper. You should not believe anything unless you have satisfied yourself with further thorough unbiased research. Big industry has only one real objective, and that is profits. One needs to be able to distinguish between reality, and product promotion with its inherent underground current of misinformation and manipulation. -

Aggression in Dogs an Overview

Behavior & Training 415.506.6280 Available B&T Services Aggression in Dogs: An Overview What is the behavior? Aggression is a natural behavior, not an aberration. Most aggression is defensive in nature – that is, the dog is reacting to what he perceives as a threat. Behavior is always in flux, and can get worse before it gets better. If your dog is aggressive, you must decide: Whether your dog is too dangerous to work with. Whether the behavior can be kept under control by managing the environment. Whether you have the ability to modify the behavior. Whether you have the time and commitment to do so. Know your dog and his body language - from behind your dog as well as beside or in front. Dogs, after all, often walk ahead of their owner. (Please review our Body Language: Speaking “Dog” handout.) Observe your dog's body language when relaxed. Observe your dog's body language when tense. Observe the DISTANCE between your dog and the object of interest. Observe your dog's body language when he is about to attack. Observe EXACTLY what sets off your dog: children/other dogs/other male or female dogs/men with beards/people in uniform. Know your own response to stress. Note what you or your family members do when your dog looks like he might aggress or when you are worried while with your dog. How do you modify the behavior? This handout will discuss some of the reasons a dog may behave aggressively and is only an overview of aggressive displays. To build an individualized behavior modification program for your dog’s needs, please contact Behavior & Training to schedule a consultation. -

Comparative Study of Free-Roaming Domestic Dog Management and Roaming Behavior Across Four Countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 Comparative study of free-roaming domestic dog management and roaming behavior across four countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda Warembourg, Charlotte ; Wera, Ewaldus ; Odoch, Terence ; Bulu, Petrus Malo ; Berger-González, Monica ; Alvarez, Danilo ; Abakar, Mahamat Fayiz ; Maximiano Sousa, Filipe ; Cunha Silva, Laura ; Alobo, Grace ; Bal, Valentin Dingamnayal ; López Hernandez, Alexis Leonel ; Madaye, Enos ; Meo, Maria Satri ; Naminou, Abakar ; Roquel, Pablo ; Hartnack, Sonja ; Dürr, Salome Abstract: Dogs play a major role in public health because of potential transmission of zoonotic diseases, such as rabies. Dog roaming behavior has been studied worldwide, including countries in Asia, Latin America, and Oceania, while studies on dog roaming behavior are lacking in Africa. Many of those studies investigated potential drivers for roaming, which could be used to refine disease control measures. However, it appears that results are often contradictory between countries, which could be caused by differences in study design or the influence of context-specific factors. Comparative studiesondog roaming behavior are needed to better understand domestic dog roaming behavior and address these discrepancies. The aim of this study was to investigate dog demography, management, and roaming behavior across four countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda. We equipped 773 dogs with georeferenced contact sensors (106 in Chad, 303 in Guatemala, 217 in Indonesia, and 149 in Uganda) and interviewed the owners to collect information about the dog [e.g., sex, age, body condition score (BCS)] and its management (e.g., role of the dog, origin of the dog, owner-mediated transportation, confinement, vaccination, and feeding practices). -

Devocalization Fact Sheet

Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association Devocalization Fact Sheet Views of humane treatment of animals in both the veterinary profession and our society as a whole are evolving. Many practicing clinicians are refusing to perform non‐therapeutic surgeries such as devocalization, declawing, ear cropping and tail docking of dogs and cats because these procedures provide no medical benefit to the animals and are done purely for the convenience or cosmetic preferences of the caregiver. At this point, devocalization procedures are not widely included in veterinary medical school curricula. What is partial devocalization? What is total devocalization? The veterinary medical term for the devocalization procedure is ventriculocordectomy. When the surgery is performed for the non‐therapeutic purpose of pet owner convenience, the goal is to muffle or eliminate dog barking or cat meowing. Ventriculocordectomy refers to the surgical removal of the vocal cords. They are composed of ligament and muscle, covered with mucosal tissue. Partial devocalization refers to removal of only a portion of the vocal cords. Total devocalization refers to removal of a major portion of the vocal cords. How are these procedures performed? Vocal cord removal is not a minor surgery by any means. It is an invasive procedure with the inherent risks of anesthesia, infection, blood loss and other serious complications. Furthermore, it does not appear to have a high efficacy rate since many patients have the procedure performed more than once, either to try to obtain more definitive vocal results or to correct unintentional consequences of their previous surgeries. Often only the volume and/or pitch of animals’ voices are changed by these procedures. -

Florida Lupine News

Florida Lupine NEWs Volume 9, Issue 4 Winter 2007 Published Quarterly FLA 2008 Rendezvous: April 18 - 20 for Members. Free to FLA's 2008 Rendezvous will be held Fri- of the Fish and Wildlife Commission and Veterinarians, day, April 18 through Sunday, April 20, at FWC Law Enforcement component, the Tech- Parramore's Resort and Campgrounds. Those nical Assistant Group (TAG). Three board Shelters, Donors, of you who attended last year know how hospi- members have also attended FWC meetings Sponsors, Rescues, table the staff members at Parramore's were, to get a handle on how the current trends re- and Animal Welfare & how receptive they were to our members and garding captive wildlife (including wolfdogs) their dogs. If you didn't make last year's Ren- may be heading, and the Board will outline Control Agencies. dezvous, which also functions as FLA's annual the information it has available by the time of meeting, you have another opportunity this the Rendezvous. (At least one board member year to visit this beautiful, not to mention ca- will try to attend any FWC meetings which FLA Directors nine welcoming, venue. We are more than for- may be held being prior to the Rendezvous.) tunate to find a facility that will still allow Al Mitchell, President Among the rules which FWC is drafting large canines in the cabins and on the premises. or is considering are "Neighbor Notification," Mayo Wetterberg Located on the St. John's River, near Astor, "dangerous" captive wildlife, and new mini- Andrea Bannon Parramore's provides all we could ask for and mum acreage and fencing requirements for Jill Parker then some. -

Wolf Outside, Dog Inside? the Genomic Make-Up of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog

Aalborg Universitet Wolf outside, dog inside? The genomic make-up of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog Caniglia, Romolo; Fabbri, Elena; Hulva, Pavel; Bolfíková, Barbora erná; Jindichová, Milena; Strønen, Astrid Vik; Dykyy, Ihor; Camatta, Alessio; Carnier, Paolo; Randi, Ettore; Galaverni, Marco Published in: B M C Genomics DOI (link to publication from Publisher): 10.1186/s12864-018-4916-2 Creative Commons License CC BY 4.0 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Caniglia, R., Fabbri, E., Hulva, P., Bolfíková, B. ., Jindichová, M., Strønen, A. V., Dykyy, I., Camatta, A., Carnier, P., Randi, E., & Galaverni, M. (2018). Wolf outside, dog inside? The genomic make-up of the Czechoslovakian Wolfdog. B M C Genomics, 19(1), [533]. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-4916-2 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

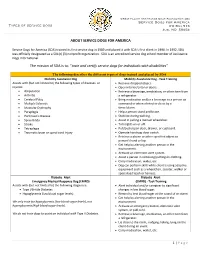

Train and Certify Service Dogs for Individuals with Disabilities”

Great Plains Assistance Dogs Foundation dba Service Dogs for America Types of service dogs PO Box 513 Jud, ND 58454 ABOUT SERVICE DOGS FOR AMERICA Service Dogs for America (SDA) trained its first service dog in 1989 and placed it with SDA’s first client in 1990. In 1992, SDA was officially designated as a 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization. SDA is an accredited service dog school member of Assistance Dogs International. The mission of SDA is to: “train and certify service dogs for individuals with disabilities” The following describes the different types of dogs trained and placed by SDA Mobility Assistance Dog Mobility Assistance Dog ‐ Task Training Assists with (but not limited to) the following types of diseases or Retrieve dropped object. injuries: Open interior/exterior doors. Amputation Retrieve a beverage, medication, or other item from Arthritis a refrigerator. Cerebral Palsy Bring medication and/or a beverage to a person on Multiple Sclerosis command or when alerted to do so by a Muscular Dystrophy timer/alarm. Paraplegia Help a person stand and brace. Parkinson’s Disease Stabilize during walking. Spina Bifida Assist in pulling a manual wheelchair. Stroke Turn lights on or off. Tetraplegia Pull/push/open door, drawer, or cupboard. Traumatic brain or spinal cord injury Operate handicap door switch. Retrieve a phone or other specified object to person’s hand or lap. Get help by alerting another person in the environment. Activate an electronic alert system. Assist a person in removing/putting on clothing. Carry medication, wallet, etc. Dog can perform skills while client is using adaptive equipment such as a wheelchair, scooter, walker or specialized leash or harness. -

Prehistoric Dogs of Bc Wolves in Sheeps' Clothing?

PREHISTORIC DOGS OF B.C. WOLVES IN SHEEPS’ CLOTHING? By GRANT KEDDIE [* This Article was originally published in: The Midden. Publication of the Archaeological Society of British Columbia, 25 (1):3-5, February 1993] Throughout the history of North American we see many varieties of native dogs. In British Colombia we find the Bear Dog of the Northern Interior and parts of the northern Coast used for hunting and packing, and a coyote-resembling dog of the southern Interior and Coast used mostly for hunting. On the southern Coast we also find what has become known as the Salish Wool Dog, kept mainly for the production of wool from its thick soft inner coat. With the use of their hair to make of blankets and capes high in trade value, these dogs made an important contribution to the status of their owners. The origin of the dog is particularly interesting. Where did they come from, and how long ago? Figure 1. These dogs seen in 1873 at the Village of Quasela in Smiths Inlet closely resemble the descriptions of Wool Dogs. They also, however, strongly resemble the Papillion breed, which was popular in Spain in the 18th century and were probably traded to B.C. natives by the Spaniards. The Papillon, possibly like the Wool Dog, is a mixture of a northern spitz and a southern variety of dog. (Blow up of RBCM PN10074 by Richard Maynard) In many parts of the world dogs have undoubtedly played a key role in the development of human hunting strategy and technology over the last 12,000 years.