Chapter 16 Giandomenica Becchio Austrian School Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rationale of Central Banking

THE RATIONALE OF CENTRAL BANKING A Liberty Press Edition Vera C. Smith THE RATIONALE OF CENTRAL BANKING and the Free Banking Alternative PREFACE BY LELAND B. YEAGER r . ,'7/ Liberty Fund Indianapolis LibertyPress is a publishing imprint of Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest-known written appearance of the word °freedom" (amagiJ, or "liberty _It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B (. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash Reprinted by permission of A. Wilson-Smith. Prelate ©1990 by Leland B Yeager All rights reserved.All inquirms should be addressed to Liberty Fund, lnc, 8335 Allison Pointe Trail, Suite 300, Indianapolis, IN 46250-1687. This book was manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smith, Vera C., 1912-1976 [Rationale of central banking] The rationale of central banking and the free banking alternative Vera C. Smith; preface by Leland B. Yeager p. cm. Reprint. Originally published" The rationale of central banking. Westminster, England: P.S King & Son Ltd., 1936 Includes bibliographical references 1. Banks and banking, Central 2. Banks and banking, Central-- Europe--History 3. Banks and banking, Central--United States-- History. HG1811.$5 1990 332.1' 1'094--dc20 90-30937 CIP ISBN 0-86597-086-6 ISBN 0-86597-087-4 (pbk) 1098765432 Contents Preface by Leland B. Yeager xiii Publisher's Note xxvii Foreword by Vera C. -

The Austrian School in Bulgaria: a History✩ Nikolay Nenovsky A,*, Pencho Penchev B

Russian Journal of Economics 4 (2018) 44–64 DOI 10.3897/j.ruje.4.26005 Publication date: 23 April 2018 www.rujec.org The Austrian school in Bulgaria: A history✩ Nikolay Nenovsky a,*, Pencho Penchev b a University of Picardie Jules Verne, Amiens, France b University of National and World Economy, Sofia, Bulgaria Abstract The main goal of this study is to highlight the acceptance, dissemination, interpretation, criticism and make some attempts at contributing to Austrian economics made in Bulgaria during the last 120 years. We consider some of the main characteristics of the Austrian school, such as subjectivism and marginalism, as basic components of the economic thought in Bulgaria and as incentives for the development of some original theoreti- cal contributions. Even during the first few years of Communist regime (1944–1989), with its Marxist monopoly over intellectual life, the Austrian school had some impact on the economic thought in the country. Subsequent to the collapse of Communism, there was a sort of a Renaissance and rediscovery of this school. Another contribution of our study is that it illustrates the adaptability and spontaneous evolution of ideas in a different and sometimes hostile environment. Keywords: history of economic thought, dissemination of economic ideas, Austrian school, Bulgaria. JEL classification: B00, B13, B30, B41. 1. Introduction The emergence and development of specialized economic thought amongst the Bulgarian intellectuals was a process that occurred significantly slowly in comparison to Western and Central Europe. It also had its specific fea- tures. The first of these was that almost until the outset of the 20th century, the economic theories and different concepts related to them were not well known. -

Free Banking in America: Disaster Or Success?

Free Banking in America: Disaster or Success? Chris Surro December 17, 2015 Even among the strongest proponents of free markets, there is widespread agreement that there is a role for government in money. We can trust the invisible hand to organize pin factories, but not to issue currency. And in a world where central banks have come to dominate around the world, it becomes hard to imagine any system other than a government monopoly on money. But that wasn't always the case. History has seen many examples where banks freely competed, generating bank notes at their own discretion, usually backed by a commodity but not by a government. In the last thirty years, even as monetary systems have largely converged to centralization, there has been a resurgence in research surrounding alternative arrangements. Economic history has a large role to play in this resurgence. Studying past examples of banking systems, analyzing their strengths and weaknesses, could help us understand and improve modern banking institutions. The American \free banking era," which lasted from roughly 1836-1862, is one ex- ample of a monetary system that has generated substantial research and debate. Before 1836, banks in the United States required a charter from the state they were located in, giving them permission to issue currency. However, starting with Michigan in 1836, many states began to enact laws allowing free entry of banks and by 1860, the number of free banking states had grown to eighteen. Traditional accounts paint a picture of the free banking era as a period of monetary chaos. Lack of regulation allowed \Wildcat banks" to issue more currency than could ever hope to be redeemed, making banking panics frequent. -

A Hayekian Theory of Social Justice

A HAYEKIAN THEORY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE Samuel Taylor Morison* As Justice gives every Man a Title to the product of his honest Industry, and the fair Acquisitions of his Ancestors descended to him; so Charity gives every Man a Title to so much of another’s Plenty, as will keep him from ex- tream want, where he has no means to subsist otherwise. – John Locke1 I. Introduction The purpose of this essay is to critically examine Friedrich Hayek’s broadside against the conceptual intelligibility of the theory of social or distributive justice. This theme first appears in Hayek’s work in his famous political tract, The Road to Serfdom (1944), and later in The Constitution of Liberty (1960), but he developed the argument at greatest length in his major work in political philosophy, the trilogy entitled Law, Legis- lation, and Liberty (1973-79). Given that Hayek subtitled the second volume of this work The Mirage of Social Justice,2 it might seem counterintuitive or perhaps even ab- surd to suggest the existence of a genuinely Hayekian theory of social justice. Not- withstanding the rhetorical tenor of some of his remarks, however, Hayek’s actual con- clusions are characteristically even-tempered, which, I shall argue, leaves open the possibility of a revisionist account of the matter. As Hayek understands the term, “social justice” usually refers to the inten- tional doling out of economic rewards by the government, “some pattern of remunera- tion based on the assessment of the performance or the needs of different individuals * Attorney-Advisor, Office of the Pardon Attorney, United States Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.; e- mail: [email protected]. -

Is the Family a Spontaneous Order?

Is the Family a Spontaneous Order? Steven Horwitz Department of Economics St. Lawrence University Canton, NY 13617 TEL (315) 229 5731 FAX (315) 229 5819 Email [email protected] Version 1.0 September 2007 Prepared for the Atlas Foundation “Emergent Orders” conference in Portsmouth, NH, October 27-30, 2007 This paper is part of a larger book project tentatively titled Two Worlds at Once: A Classical Liberal Approach to the Evolution of the Modern Family. I thank Jan Narveson for an email exchange that prompted my thinking about many of the ideas herein. Work on this paper was done while a visiting scholar at the Social Philosophy and Policy Center at Bowling Green State University and I thank the Center for its support. 1 The thirty or so years since F. A. Hayek was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Science has seen a steady growth in what might best be termed “Hayek Studies.” His ideas have been critically assessed and our understanding of them has been deepened and extended in numerous ways. At the center of Hayek’s work, especially since the 1950s, was the concept of “spontaneous order.” Spontaneous order (which would be more accurately rendered as “unplanned” or “undesigned” or “emergent” order) refers, at least in the social world, to those human practices, norms, and institutions that are, in the words of Adam Ferguson, “products of human action, but not human design.” For Hayek, this concept was central to his critique of “scientism,” or the belief that human beings could control and manipulate the social world with the (supposed) methods of the natural sciences. -

How Far Is Vienna from Chicago? an Essay on the Methodology of Two Schools of Dogmatic Liberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Paqué, Karl-Heinz Working Paper — Digitized Version How far is Vienna from Chicago? An essay on the methodology of two schools of dogmatic liberalism Kiel Working Paper, No. 209 Provided in Cooperation with: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) Suggested Citation: Paqué, Karl-Heinz (1984) : How far is Vienna from Chicago? An essay on the methodology of two schools of dogmatic liberalism, Kiel Working Paper, No. 209, Kiel Institute of World Economics (IfW), Kiel This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/46781 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Kieler Arbeitspapiere Kiel Working Papers Working Paper No. -

API-119: Advanced Macroeconomics for the Open Economy I, Fall 2020

Sep 1, 2020 API-119: Advanced Macroeconomics for the Open Economy I, Fall 2020 Harvard Kennedy School Course Syllabus: prospectus, outline/schedule and readings Staff: Professor: Jeffrey Frankel [email protected] Faculty Assistant: Minoo Ghoreishi [email protected] Teaching Fellow: Can Soylu Course Assistants: Julio Flores, Alberto Huitron & Yi Yang. Email address to send all questions for the teaching team: [email protected]. Times: Lectures: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 10:30-11:45 a.m. EST.1 Review Sessions: Tuesdays, 12:30-1:30 pm; Fridays, 1:30-2:30 pm EST.2 Final exam: Friday, Dec. 11, 8:00-11:00 am EST. Prospectus Course Description: This course is the first in the two-course sequence on Macroeconomic Policy in the MPA/ID program. It particularly emphasiZes the international dimension. The general perspective is that of developing countries and other small open economies, defined as those for whom world income, world inflation and world interest rates can be taken as given, and possibly the terms of trade as well. The focus is on monetary, fiscal, and exchange rate policy, and on the determination of the current account balance, national income, and inflation. Models of devaluation include one that focuses on the price of internationally traded goods relative to non-traded goods. A theme is the implications of increased integration of global financial markets. Another is countries’ choice of monetary regime, especially the degree of exchange rate flexibility. Applications include Emerging Market crises and problems of commodity-exporting countries. (Such topics as exchange rate overshooting, speculative attacks, portfolio diversification and debt crises will be covered in the first half of Macro II in February-March.) Nature of the approach: The course is largely built around analytical models. -

FALL 2015 Journal of Austrian Economics

The VOL. 18 | NO. 3 | 294–310 QUArtERLY FALL 2015 JOURNAL of AUSTRIAN ECONOMICS PRAXEOLOGY OF COERCION: CATALLACTICS VS. CRATICS RAHIM TAGHIZADEGAN AND MARC-FELIX Otto ABSTRACT: Ludwig von Mises’s most important legacy is the foundation and analysis of catallactics, i.e. the economics of interpersonal exchange, as a sub-discipline of praxeology, the science of human action. In this paper, based both on Mises’s methodical framework and on insights by Tadeusz Kotarbinski and Max Weber, a “praxeology of coercion,” or, more precisely, an analysis of interpersonal actions involving threats, is developed. Our investigation yields both a reviewed taxonomy of human action and a first analysis of the elements of this theory, which we term cratics. This shall establish the basis for adjacent studies, furthering Mises’s project regarding the science of human action. KEYWORDS: Austrian school, praxeology, catallactics, coercion JEL CLASSIFICATION: B53 Rahim Taghizadegan ([email protected]) is director of the academic research institute Scholarium (scholarium.at) in Vienna, Austria, lecturer at several univer- sities and faculty member at the International Academy of Philosophy in Liech- tenstein. Marc-Felix Otto ([email protected]) is equity partner at the consulting firm The Advisory House in Zurich, Switzerland. Both authors would like to thank the research staff at the Scholarium for their help and input, in particular Johannes Leitner and Andreas M. Kramer. 294 Rahim Taghizadegan and Marc-Felix Otto: Praxeology Of Coercion… 295 INTRODUCTION he Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises intended to re-establish economics on a deductive basis, with the subjective Tvaluations, expectations, and goals of acting humans at the center, following the tradition of the “Austrian School” (see Mises, 1940 and 1962). -

Cryptocurrencies As an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems David A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons at Buffalo State State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Applied Economics Theses Economics and Finance 5-2018 Cryptocurrencies as an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems David A. Georgeson State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Tae-Hee Jo, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Economics & Finance First Reader Tae-Hee Jo, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Economics & Finance Second Reader Victor Kasper Jr., Ph.D., Associate Professor of Economics & Finance Third Reader Ted P. Schmidt, Ph.D., Professor of Economics & Finance Department Chair Frederick G. Floss, Ph.D., Chair and Professor of Economics & Finance To learn more about the Economics and Finance Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to http://economics.buffalostate.edu. Recommended Citation Georgeson, David A., "Cryptocurrencies as an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems" (2018). Applied Economics Theses. 35. http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/economics_theses/35 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/economics_theses Part of the Economic Theory Commons, Finance Commons, and the Other Economics Commons Cryptocurrencies as an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems By David A. Georgeson An Abstract of a Thesis In Applied Economics Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts May 2018 State University of New York Buffalo State Department of Economics and Finance ABSTRACT OF THESIS Cryptocurrencies as an Alternative to Fiat Monetary Systems The recent popularity of cryptocurrencies is largely associated with a particular application referred to as Bitcoin. -

Economist Series, GS-0110 TS-54 December 1964, TS-45 April 1963

Economist Series, GS-0110 TS-54 December 1964, TS-45 April 1963 Position Classification Standard for Economist Series, GS-0110 Table of Contents SERIES DEFINITION.................................................................................................................................... 2 GENERAL STATEMENT.............................................................................................................................. 2 SPECIALIZATION AND TITLING PATTERN .............................................................................................. 5 SUPERVISORY POSITIONS...................................................................................................................... 13 FUNCTIONAL PATTERNS AND GRADE-LEVEL DISTINCTIONS .......................................................... 13 ECONOMIST, GS-0110-05..................................................................................................................... 15 ECONOMIST, GS-0110-07..................................................................................................................... 16 ECONOMIST, GS-0110-09..................................................................................................................... 17 ECONOMIST, GS-0110-11..................................................................................................................... 18 ECONOMIST, GS-0110-12..................................................................................................................... 20 ECONOMIST, GS-0110-13.................................................................................................................... -

Tomasz Koźluk Counsellor to the OECD Chief Economist

Tomasz Koźluk Counsellor to the OECD Chief Economist Contact information [email protected] Education PhD, European University Institute, Florence, 2007 MA, International Economics, Sussex University, 2002 MA, Economics Department, Warsaw University, 2002 Professional experience 2021-present Counsellor to the OECD Chief Economist 2012-2017 Senior Economist, Head of Green Growth Workstream, joint Economics Department & Environment Directorate, OECD Chair of Research Committee on Metrics and Indicators, Green Growth, Green Growth Knowledge Platform 2007-2011 Economist, Economics Department , OECD Structural Policy Analysis Division, Macroeconomic Analysis Division and Country Studies Branch 2004-2007 Researcher, Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition; European Central Bank (Financial Research); European Investment Bank (Economic and Financial Studies); CASE; Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, EUI Selected publications and working papers Empirical projects linking environmental policies and economic outcomes (http://oe.cd/eps) "Environmental policies and productivity growth: Evidence across industries and firms," (2017), Journal of Environmental Economics and Management vol. 81, (with V. Zipperer and S. Albrizio) “Environmental Policies and Productivity Growth – A Critical Review of Empirical Findings”, (2014), OECD Journal: Economic Studies, OECD Publishing, vol. 2014(1), (with V. Zipperer) “Effects of vintage-differentiated environmental regulations - evidence from survival analysis of coal-fired power plants”, -

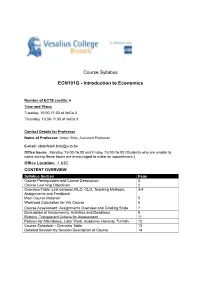

Course Syllabus ECN101G

Course Syllabus ECN101G - Introduction to Economics Number of ECTS credits: 6 Time and Place: Tuesday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Thursday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Contact Details for Professor Name of Professor: Abdel. Bitat, Assistant Professor E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday, 15:00-16:00 and Friday, 15:00-16:00 (Students who are unable to come during these hours are encouraged to make an appointment.) Office Location: -1.63C CONTENT OVERVIEW Syllabus Section Page Course Prerequisites and Course Description 2 Course Learning Objectives 2 Overview Table: Link between MLO, CLO, Teaching Methods, 3-4 Assignments and Feedback Main Course Material 5 Workload Calculation for this Course 6 Course Assessment: Assignments Overview and Grading Scale 7 Description of Assignments, Activities and Deadlines 8 Rubrics: Transparent Criteria for Assessment 11 Policies for Attendance, Later Work, Academic Honesty, Turnitin 12 Course Schedule – Overview Table 13 Detailed Session-by-Session Description of Course 14 Course Prerequisites (if any) There are no pre-requisites for the course. However, since economics is mathematically intensive, it is worth reviewing secondary school mathematics for a good mastering of the course. A great source which starts with the basics and is available at the VUB library is Simon, C., & Blume, L. (1994). Mathematics for economists. New York: Norton. Course Description The course illustrates the way in which economists view the world. You will learn about basic tools of micro- and macroeconomic analysis and, by applying them, you will understand the behavior of households, firms and government. Problems include: trade and specialization; the operation of markets; industrial structure and economic welfare; the determination of aggregate output and price level; fiscal and monetary policy and foreign exchange rates.